Hip Arthroscopy

Michael H. Dienst MD

Various anatomical features make placement of portals and movement of the arthroscope and instruments within the hip more difficult than in other joints.

The central compartment (CC) of the hip, made up of the lunate cartilage, acetabular fossa, ligamentum teres and the loaded articular surface of the femoral head, can be visualized almost exclusively with traction.

The peripheral compartment (PC) can be better seen without traction. The PC consists of the unloaded cartilage of the femoral head, the femoral neck with the medial, anterior, and posterolateral synovial folds and the articular capsule with the intrinsic ligaments, including the zona orbicularis.

The key to an accurate and complete diagnosis of lesions within the hip joint is a systematic approach to viewing. A methodical sequence of examination should be developed, progressing from one part of the joint cavity to another.

Evaluation should exclude spinal, abdominal-inguinal, neurologic, and rheumatologic diagnoses before the patient is considered for a diagnostic hip scope.

For contouring of the femoral head in CAM-type of impingement, the arthroscope is introduced via the anterolateral or distal anterolateral portal, the shaver and burr are placed via the anterior portal. Usually, trimming of the femoral head starts at the insertion of the medial synovial fold medially and extends up to the lateral synovial fold laterally.

The need for less invasive, joint preserving, operative techniques has led to a massive improvement of minimally invasive procedures not only of the knee and shoulder, but also of arthroscopic surgery of the hip joint. For the past ten years, many surgeons have been contributing to the development and improvement of innovative techniques of hip arthroscopy. With its increasing frequency has grown the knowledge of the normal hip anatomy with the ability to differentiate between anatomic variations and pathologic conditions of the hip joint. Moreover, hip arthroscopy has left its limited function as a diagnostic tool and resection operation such as removal of loose bodies and resection of the acetabular labrum or ligamentum teres. It has made the step to become a reconstructive procedure in the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement, repair of a torn acetabular labrum and for treatment of cartilage defects.

Based on the classification of the arthroscopic compartments of the hip joint, the following report presents the current diagnostic and operative technique of hip arthroscopy of both compartments with and without traction. A systematic mapping of the normal arthroscopic anatomy is included followed by a summary of indications, contraindications, and complications.

Placement of portals and maneuverability of the arthroscope and instruments within the hip joint is more difficult than in other joints. This is related to various anatomical features: a thick soft tissue mantle, close proximity of two major neurovascular bundles, a strong articular capsule, a relatively small intraarticular volume, permanent contact of the articular surfaces, and the sealing of the deep, central part of the joint by the acetabular labrum. Thus, if no traction is applied to the hip, only a small film of synovial fluid separates the

articular surface of the femoral head from the lunate cartilage and acetabular labrum (“artificial space”).

articular surface of the femoral head from the lunate cartilage and acetabular labrum (“artificial space”).

The anatomy of the acetabular labrum must be considered before accessing the hip joint. The labrum seals the joint space between the lunate cartilage and the femoral head (1,2,3). To overcome the vacuum force and passive resistance of the soft tissues, traction is needed to separate the head from the socket, to elevate the labrum from the head and to allow the arthroscope and other instruments access to the narrow “artificial space” between the weight-bearing cartilage of the femoral head and acetabulum. However, if traction is applied, the joint capsule is tensioned and the joint space peripheral to the acetabular labrum decreases. Thus, in order to maintain the space of the peripheral hip joint cavity for better visibility and maneuverability during arthroscopy, traction should be avoided.

In consequence, Dorfmann and Boyer (4,5) divided the hip arthroscopically into 2 compartments separated by the labrum. The first is the central compartment (CC) comprising the lunate cartilage, the acetabular fossa, the ligamentum teres, and the loaded articular surface of the femoral head. This part of the joint can be visualized almost exclusively with traction. The second is the peripheral compartment (PC) consisting of the unloaded cartilage of the femoral head, the femoral neck with the medial, anterior, and posterolateral synovial folds (Weitbrecht’s ligaments) and the articular capsule with its intrinsic ligaments including the zona orbicularis. This area can be better seen without traction (6).

Positioning

Hip arthroscopy, with and without traction, can be performed in the lateral (7,8) or supine position (6,9,10). Some authors claim that there are advantages to the lateral position, including better access to the posterolateral area (11,12), and better application of traction in line with the femoral neck (13). However, this author’s studies in fresh cadaveric hip joints showed no significant differences in distraction of the hip between the supine and the lateral position (14). From the author’s experience, the decision whether to use the supine or lateral position appears to be more a matter of individual training and habit of use. Because of the almost exclusive use of the anterolateral and anterior portals during hip arthroscopy without traction, the author prefers the supine position (5,6,15,16). The author usually combines the technique with traction and without traction. If distraction of the CC is not sufficient, only the PC is operated without traction. The combination of both techniques is important to allow a complete diagnostic arthroscopic examination of the hip.

Hip Arthroscopy With Traction

In the supine position, the patient is pulled distally onto the counterpost, so that the medial side of the thigh presses against the post. This is important not only to avoid pressure to the perineum and pudendal nerve, but also to increase the cantilever effect of the post on subsequent adduction of the leg (3). Both feet and ankles are well padded and fixed tightly into the traction boots. The ipsilateral hip is slightly flexed to 10 to 20 degrees for relaxation of the strong anterior parts of the hip joint capsule, and tensioned by lengthening of the extension bar. The leg is adducted to about 0 to 10 degrees of abduction in order to increase the distraction force vector by a cantilever effect of the counterpost (3) (Fig 26-1). The first AP radiograph is taken with the image intensifier. The hip is then distracted by pulling with the traction module until the joint vacuum is broken. Another radiograph is taken to assess distraction of the hip joint (Fig 26-2). Traction is released until the hip is scrubbed and draped and portals to the CC are established. Sometimes distraction may be moderate only. In these cases, better separation can often be achieved once the vacuum seal is broken with the spinal needle. However, if adequate distraction cannot be achieved with a combination of traction, distension, and proper joint positioning, the surgeon needs to be prepared to abandon arthroscopy of the CC. Under these circumstances, he can still perform arthroscopy of the PC without traction.

Hip Arthroscopy Without Traction

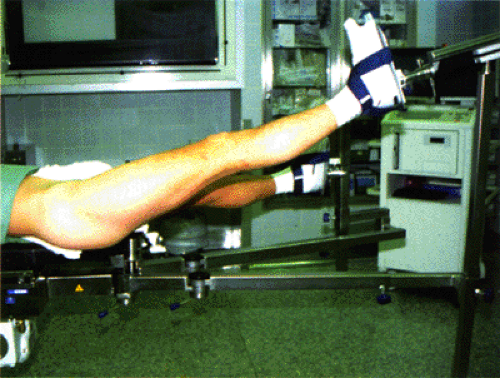

Traction is released; the foot is taken out of the traction boot and covered with a sterile hood. The traction bar and the counterpost are removed, and the leg rest extension is reattached to the extension table. The hip can be flexed, rotated and ab-/adducted to the desired position (Fig 26-3). Cadaver experiments and in vivo experience (17) have shown that free draping and a good range of movement is important to relax parts of the capsule and increase the intra-articular volume of the area that is inspected (18).

Distraction and Distension

For arthroscopy of the CC, sufficient joint distraction is necessary: More space will improve the intra-articular maneuverability of the arthroscope and additional instruments

and may reduce the risk of intra-articular complications, such as damage to the acetabular labrum and articular cartilage. On the other hand, high traction forces can cause nerve and soft tissue injuries around the hip, at the perineum, and the ankle (10,12,19,20,21).

and may reduce the risk of intra-articular complications, such as damage to the acetabular labrum and articular cartilage. On the other hand, high traction forces can cause nerve and soft tissue injuries around the hip, at the perineum, and the ankle (10,12,19,20,21).

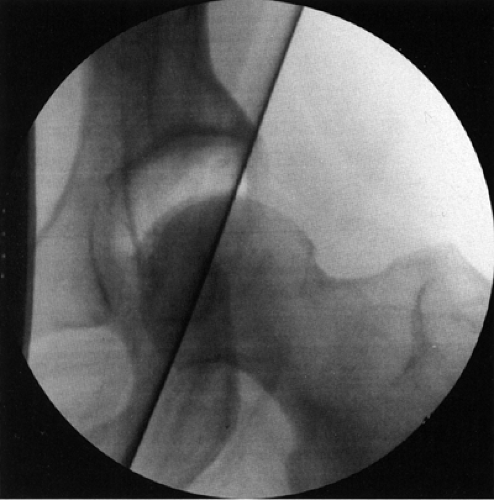

Fig 26-2. Preoperative AP radiographs after application of traction with breakage of the joint seal. (Courtesy of Michael Dienst, MD.) |

Little is known on the direct effect of tension of the femoral and sciatic nerve during hip arthroscopies. To my knowledge, only temporary sensory and motor deficits of the femoral and sciatic nerve were reported. Griffin and Villar (21) identified in their retrospective analysis of 640 consecutive hip arthroscopies: 3 patients with temporary sciatic nerve palsy; and one patient with temporary femoral nerve palsy. All deficits recovered within the first few hours postoperatively. There is consensus not to exceed traction time over 2 hours. In addition, flexion over 20 degrees should be avoided to not increase tension to the sciatic nerve. This author’s studies have shown that creep of the periarticular structures reduces the need for force to maintain distraction (22). Thus traction should be reduced as soon as the hip has been distended and the portals have been established.

The effect of distension has already been studied. In-vivo and cadaver studies have shown that the breakage of the joint vacuum leads to a significant increase of distraction (3,23). Distraction can be improved by additional distension up to 81% in vivo (23). Thus, the joint should be distended with a spinal needle before the first portal is established.

A complete diagnostic round trip and access to damaged structures can be achieved only with precise portal placement. In addition, potential complications of portal placement, mainly to the CC, have to be considered. The space between the acetabular labrum and the cartilage of the femoral head is small, so both structures are at risk for direct lesions from scuffing to deep cartilage defects or labral tears. Neurovascular structures are close, but usually not at risk, if distinct lines are not crossed. So, the surgeon should take his time especially for this part of the procedure.

From my experience, fluoroscopy is mandatory for safe portal placement at least for the first portal to each compartment. Further access of additional portals can be controlled via the arthroscope and triangulation. Special guides may be of further help (24). Beneficial is the use of cannulated trokars, or dilating instruments, for introduction of the sheaths and flexible working cannulas.

Central Compartment

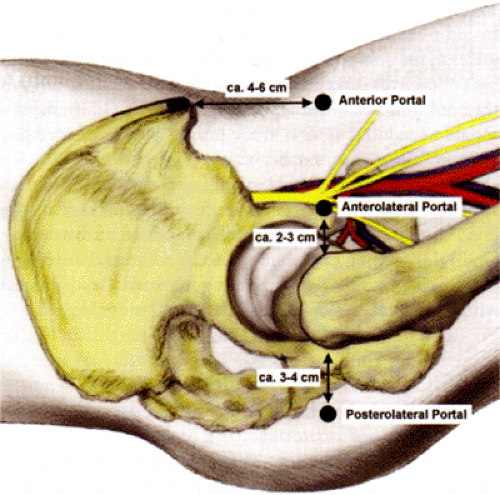

Different portals are currently being used. Some surgeons prefer a 2-portal technique, others a 3-portal technique for arthroscopy of the CC. From our experience a 2-portal technique may be sufficient in hips with very good distraction. However, usually a 3-portal access to the hip is required for a complete inspection and access to different structures (Fig 26-4).

The following paragraphs describe the “classic” technique for portal placement to the CC. However, the author has established a new technique, which he has been increasingly using over the past year. This technique is presented afterward.

Anterolateral and Lateral Portal

With respect to neurovascular structures both the anterolateral and lateral portal are most centrally in the safe zone for arthroscopy (25). For placement of the anterolateral portal, the skin is incised about 2 cm anterior to the anterosuperior

edge of the greater trochanter. The needle is directed about 10 to 20 degrees cranially and 20 to 30 degrees posteriorly. It penetrates the gluteus medius and/or the tensor fasciae latae before entering the joint. The lateral portal may be used alternatively to the anterolateral portal. It lies just proximal to the tip of the greater trochanter. Anterior and posterolateral portal placement can be controlled arthroscopically as soon as the arthroscope is introduced via the anterolateral portal.

edge of the greater trochanter. The needle is directed about 10 to 20 degrees cranially and 20 to 30 degrees posteriorly. It penetrates the gluteus medius and/or the tensor fasciae latae before entering the joint. The lateral portal may be used alternatively to the anterolateral portal. It lies just proximal to the tip of the greater trochanter. Anterior and posterolateral portal placement can be controlled arthroscopically as soon as the arthroscope is introduced via the anterolateral portal.

Posterolateral Portal

The skin is incised about 3 cm posterior to the posterosuperior edge of the greater trochanter at the same height as the anterolateral portal. The needle is directed about 10 degrees cranially, and 30 degrees anteriorly, penetrating the gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus, and the capsule close to the posterior horn of the labrum. Here, the distance to the sciatic nerve was measured with a minimum of 2 cm (25).

Anterior Portal

The skin incision for this portal is 4 to 6 cm distally to the anterior superior iliac spine. The needle is directed about 30 degrees medially, and 30 to 45 degrees cranially. On its way into the joint it penetrates the muscle belly of the sartorius and the rectus femoris, before entering the joint (25). If the entry point for the anterior portal is not placed further medially, the minimum distance to the femoral nerve has been measured as 2.7 cm in cadavers (25).

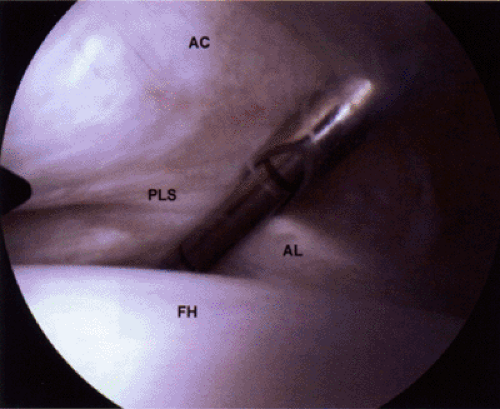

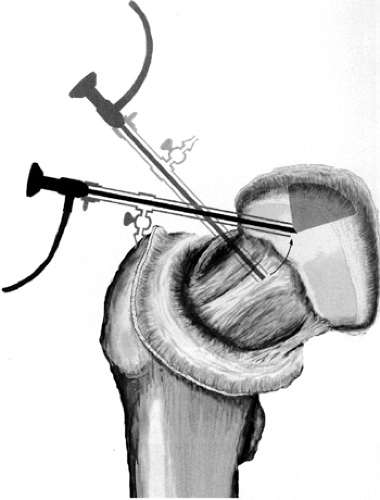

Since 2003, the author has used a “new” technique for the first access to the CC (26). Under fluoroscopy, the arthroscope is introduced via the anterolateral portal to the anterior neck area of the PC, in the standard technique using a needle, guidewire, and cannulated trocars. The 30 degree arthroscope is advanced over the head-neck-transition, into the anterior head area, and changed to the 70 degree arthroscope, to visualize the junction of the anterior labrum and anterior femoral head cartilage (Fig 26-5). The anterior portal to the CC can be placed under arthroscopic control. Entry site and direction of the needle are the same as described before. The tip of the needle with a guide wire can be maneuvered precisely between the labrum and the femoral head cartilage (Fig 26-6). As soon as the anterior portal is placed to the CC, further portal placement can be controlled via the 70 degree arthroscope with less risk of injury to the labrum and cartilage.

Fig 26-5. Position of the arthroscope for inspection of the peripheral anterior head area for subsequent placement of the anterior portal to the CC. (Courtesy of Michael Dienst, MD.) |

When all 3 portals are established, the diagnostic round trip and operative treatment, in case of pathologic changes of the CC, can be initiated.

Peripheral Compartment

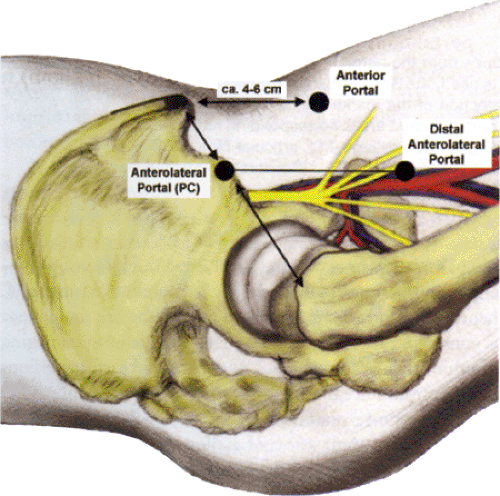

From Dorfmann and Boyer’s (5), and my experience (6,27), a comprehensive overview can be obtained from the anterolateral portal only. Because the soft tissue mantle is relatively thin and the position of the portal is near the lateral cortex of the femoral neck, maneuverability of the arthroscope is sufficient for moving the arthroscope into the medial recess, gliding over the anterior surface of the femoral head to the

lateral recess, and frequently passing the lateral cortex of the femoral neck for inspection of the posterior recess (6). With the need for better access to the lateral and posterolateral neck and head area for therapy, or CAM-type of femoroacetabular impingement, a 3 portal technique for the PC has recently been established (Fig 26-7).

lateral recess, and frequently passing the lateral cortex of the femoral neck for inspection of the posterior recess (6). With the need for better access to the lateral and posterolateral neck and head area for therapy, or CAM-type of femoroacetabular impingement, a 3 portal technique for the PC has recently been established (Fig 26-7).

The position and direction of the anterolateral portal (PC) is different to the anterolateral portal to the CC. The incision lies more proximally and anteriorly. Usually the perfect spot for the skin incision can be found by palpating a soft spot, one third of the distance of a line drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine to the tip of the greater trochanter. Here, one can feel the anterior margin of the gluteus medius. The needle thus penetrates only the tensor fasciae latae on its way to the joint capsule. Under fluoroscopy, the needle is directed perpendicular to the femoral neck axis to the anterolateral transition from the femoral head to the femoral neck.

Anterior portal (PC)

Using the same skin incision of the anterior portal to the CC, the needle is directed more inferiorly and not so far medially aiming to the anterior junction of the femoral head and neck.

Distal anterolateral portal (PC)

Especially in order to improve viewing of the anterolateral and lateral head and neck areas during recontouring of the femoral head in impingement surgery, placement of another anterolateral portal further distally, is beneficial. The portal incision lies at the junction of a vertical line drawn from the anterolateral portal (PC) with the superior border of the femoral neck. The needle is directed to the anterior neck area.

Similar to the knee joint, the key to an accurate and complete diagnosis of lesions within the hip joint is a systematic approach to viewing. A methodical sequence of examination should be developed, progressing from one part of the joint cavity to another and systematically carrying out this sequence in every hip.

Central Compartment

For a complete inspection of the CC all 3 portals are used. No matter from which portal the 30 degree arthroscope allows inspection of the acetabular fossa and central parts of the lunate cartilage only. For viewing of the peripheral parts of the lunate cartilage, the acetabular labrum, perilabral recess, and the more circumferential aspects of the femoral head, the use of the 70 degree arthroscope is mandatory (Fig 26-8). From each portal, different areas within the CC can be inspected. Both lenses are brought into all 3 portals scanning the complete CC.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree