Hip Arthroplasty for Intertrochanteric Hip Fractures

George J. Haidukewych

The vast majority of intertrochanteric hip fractures treated with internal fixation heal. However, certain unfavorable fractures patterns, fractures in patients with severely osteopenic bone, or patients with poor hardware placement, can lead to internal fixation failure (nonunion). Randomized prospective studies of displaced femoral-neck fractures in elderly osteoporotic patients have shown a high complication rate associated with internal fixation of these injuries. For this reason, most surgeons favor arthroplasty, which has a documented excellent success rate and offers the advantage of early weight bearing. This has led some surgeons to consider the use of a prosthesis in the management of selected, osteoporotic, intertrochanteric, hip fractures. In theory, this may allow earlier mobilization and minimize the chance of internal fixation failure and need for re-operation. The use of arthroplasty in this setting, however, poses its own unique challenges including the need for so-called “calcar replacing” prostheses and it raises questions regarding the need for acetabular resurfacing and the management of the often-fractured greater trochanteric fragment. The purpose of this chapter is to review the indications, surgical techniques, and specific technical details needed to achieve a successful outcome. Also addressed are the potential complications of hip arthroplasty for fractures of the intertrochanteric region of the femur.

Indications

The vast majority of intertrochanteric hip fractures, whether stable or unstable, will heal uneventfully with accurately placed internal-fixation devices. When the procedure is done correctly, the fixation failure rate should be minimal. European studies have found that hip arthroplasty can lead to successful outcomes; however, there is a higher perioperative mortality rate among these patients compared to those who undergo internal fixation. Therefore, the indications for hip arthroplasty for peritrochanteric fractures include patients with neglected intertrochanteric fractures when attempts at open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) are unlikely to succeed; pathologic fractures due to neoplasm; internal

fixation failures or established nonunions where the patient’s age and remaining proximal-bone stock precludes a revision internal-fixation attempt; (very rarely) in patients with severe preexisting, symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hip; and an unstable fracture pattern. Recent studies have documented that hip arthroplasty for salvage of failed internal fixation provides predictable pain relief and functional improvement.

fixation failures or established nonunions where the patient’s age and remaining proximal-bone stock precludes a revision internal-fixation attempt; (very rarely) in patients with severe preexisting, symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hip; and an unstable fracture pattern. Recent studies have documented that hip arthroplasty for salvage of failed internal fixation provides predictable pain relief and functional improvement.

Patient Evaluation and Preoperative Planning

Because these patients are typically elderly and frail with multiple medical co-morbidities, a thorough medical evaluation is recommended. Preoperative correction of dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and anemia is important. In general, surgery is performed within 48 hours of injury to avoid prolonged recumbency.

Plain anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the hip, femur, and pelvis are important for preoperative planning. If the surgeon has any concern of a pathologic fracture, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning can occasionally be helpful. If a pathologic fracture due to metastasis is diagnosed, full-length femur radiographs are even more critical in evaluating any distal lesions that would need to be addressed. Appropriate imaging of the proximal fragment is important to allow templating of the femoral component for length or offset and to determine whether any proximal calcar augmentation will be necessary to restore the normal neck-shaft relationship. Careful scrutiny of the hip joint is necessary to detect evidence of acetabular degenerative change that would make total hip arthroplasty more attractive than hemi-arthroplasty. A final decision is often made intraoperatively after visual inspection of the quality of the remaining acetabular cartilage. If previous hardware from internal fixation is present, specific screwdrivers and a broken screw removal set, with or without the use of fluoroscopy, may assist the surgeon in hardware removal. It is wise to have implant-specific extraction tools available. Obtaining the original operative note can assist the surgeon in determining the implant manufacturer if it is not recognized from the radiographs.

Often it is difficult to ascertain preoperatively whether hemi-arthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty is appropriate, and whether cemented or uncemented femoral component fixation is indicated. I prefer to have both acetabular resurfacing and femoral-component fixation options available intraoperatively. Although having such a large inventory of implants available for a single case is laborious, it is wise to be prepared for the unexpected situations that can be found during these challenging reconstructions.

To evaluate infection as a potential etiology for failed internal fixation, I recommend that a complete blood count with differential, a sedimentation rate, and a C-reactive protein be obtained preoperatively. I have not found aspiration to be predictable in the setting of fixation failure and rely on preoperative serologies and intraoperative frozen-section histology for decision making.

Surgical Technique

The exact surgical technique will vary, of course, based on whether the reason for performing the arthroplasty is an acute fracture, a neglected fracture, a pathologic fracture, or a nonunion with failed hardware. However, many surgical principles are commonplace regardless of the preoperative diagnosis.

The patient is positioned in lateral decubitus position on the operating room table, and an intravenous antibiotic, typically a first-generation cephalosporin, is given. Careful padding of the down axilla, peroneal nerve area, and ankle can minimize the chance of a neurological or skin pressure problem due to positioning. A stable horizontal position can guide the surgeon to appropriate pelvic positioning, which will facilitate proper acetabular-component implantation. Several commercially available hip positioners are available to simplify accurate and stable pelvic positioning. Consideration should be given to the use of intraoperative blood salvage (cell saver), as these surgeries can be long and bloody.

The leg is prepped and draped in the usual fashion, and if possible, the previous incisions are used. If no previous incision is present, then a simple curvilinear incision centered on the greater trochanter will suffice. The fascia is incised in line with the skin incision and the status of the greater trochanter is evaluated. If the greater trochanter is not fractured, either an anterolateral or posterolateral approach can be used effectively based on surgeon preference. In the acute fracture situation it is always preferable, if possible, to leave the abductor–greater trochanter–vastus lateralis complex intact and immobilized in a long sleeve as much as possible during the reconstruction.

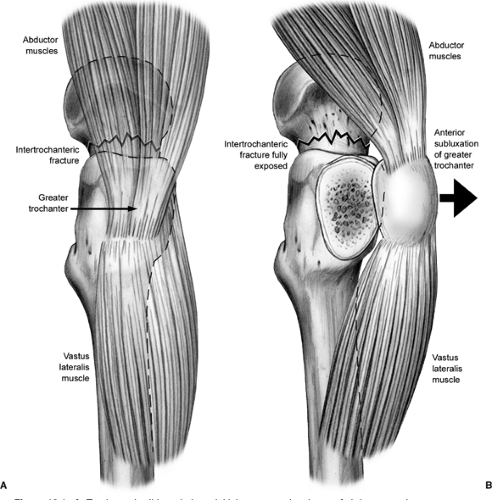

In nonunions or neglected fractures, the trochanter may be malunited and preclude access to the intramedullary canal. In this situation the so-called “trochanteric slide” technique may be useful (Fig. 18.1). This technique of preserving the vastus-trochanter-abductor sleeve may minimize the chance of so-called “trochanteric escape” and should be used whenever possible.

If hardware is present in the proximal femur, it is wise to dislocate the hip prior to hardware removal. The torsional stresses on the femur during surgical dislocation can be large, especially in these typically stiff hips, and iatrogenic femur fracture can occur with attempted hip dislocation. If previous surgery has been performed, I prefer to obtain intraoperative cultures and frozen section pathology. If there is evidence of acute inflammation or other gross clinical evidence of infection, then I recommend removal of all hardware, careful debridement of all tissues, and resection of the proximal femoral-head fragment with placement of an antibiotic impregnated polymethacrylate spacer. The reconstruction is then performed in a delayed fashion after a period of organism-specific intravenous antibiotics based on the sensitivities obtained from deep intraoperative cultures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree