Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome

Rita D. Sheth

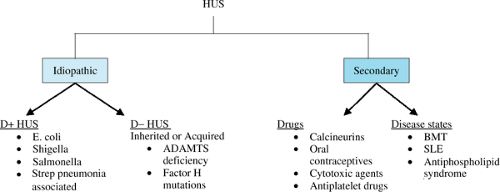

The hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), first described in 1955, is characterized by the triad of nephropathy, thrombocytopenia, and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. HUS is a heterogeneous group of disorders that have a common end result. To differentiate the pathogenesis and clinical outcome, the following classification has been proposed (Fig. 457.1):

Typical or diarrhea-associated (D+ HUS): This is the classic HUS syndrome that presents in infants or small children after a prodrome of bloody diarrhea. The most common infectious agent associated with D+ HUS is the verotoxin-producing strain of Escherichia coli. Other enterotoxin producing bacteria such as enteropathic E. coli, Shigella, or Salmonella also have been associated with D+ HUS. Neuraminidase-producing streptococcal infections also can be associated with a typical HUS picture in the absence of a diarrheal illness. In these cases, the prodrome is often a respiratory illness with Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Atypical or D- HUS: This category includes those patients with HUS who usually are not associated with an infectious illness or prodrome, hence the absence of diarrhea (D-). The etiology of HUS in this category includes familial cases with genetic mutations.

Secondary: Secondary HUS occurs secondary to drugs (calcineurin inhibitors, cytotoxic agents, antiplatelet agents, and oral contraceptives) or is associated with certain conditions (bone marrow transplantation, pregnancy, lupus, or the antiphospholipid syndrome).

D+ HUS

Epidemiology

D+ HUS is largely a disease of infants and children. The syndrome is endemic in Argentina, southern Africa, and the western United States. It has no predilection for either gender or ethnic background. Post diarrheal HUS occurs more frequently during warmer months. Epidemics of HUS have been associated with the contamination of a variety of food products. The summer disease incidence peak correlates with the higher incidence of positive enterohemorrhagic E. coli fecal cultures in cattle during the warmer months.

HUS associated with streptococcal infections is less common and occurs in younger children, typically after a respiratory illness, such as lobar pneumonia.

Pathogenesis

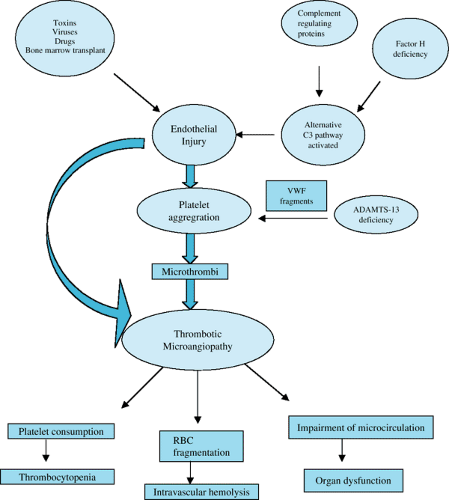

The inciting event is thought to be direct endothelial damage by toxins produced by the infectious organism (Fig. 457.2). These toxins are released in the gut, absorbed in the blood stream, and bind to neutrophil surfaces in the systemic circulation. These toxins then bind to those specific receptors (Gb3) found in high concentration in renal microvasculature endothelial cells, and the result is cellular damage and death. Verotoxins also induce the release of proinflammatory cytokines and procoagulant factors. Endothelial cell damage secondary to enterotoxins and proinflammatory cytokines causes a cascade of events that results in cell wall damage and the formation of platelet and fibrin clots in the small capillaries and arterioles of the kidney. Circulating red cells are deformed and fragmented, resulting in the microangiopathic hemolytic anemia seen in HUS. The ongoing formation of microthrombi in the damaged vessels results in platelet consumption and thrombocytopenia. The occlusion of the renal microvasculature with platelet and fibrin thrombi results in glomerular damage and renal failure.

In patients with Streptococcus pneumoniae–associated HUS, normally occurring Thomsen-Friedenreich antigens are exposed by streptococcal neuraminidase. These antigens bind with preformed IgM antibodies and cause subsequent erythrocyte, platelet, and endothelial injury, and thus begins the cascade of events leading to microangiopathic vascular injury.

FIGURE 457.2. Schematic of HUS pathogenesis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|