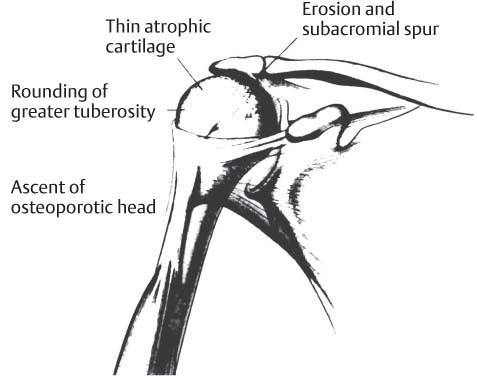

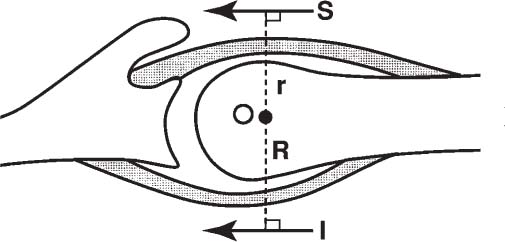

7 Hemiarthroplasty for Rotator Cuff–Tear Arthropathy In 1853, Adams initially described rotator cuff arthropathy (RCA), when he observed individuals with chronic rotator cuff (RC) tears leading to severe arthritis.1,2 The term cuff–tear arthropathy, however, was coined by Neer and colleagues in 1977 and formally described in 1983.3 Neer et al reported on the pathoanatomical changes that occurred with chronic massive RC tears, including structural changes in the humeral head (atrophic cartilage, osteoporotic subchondral bone), coracoacromial arch, and glenoid (absent cartilage and sclerosis at point of contact with humeral head) surfaces. Superior displacement of the humerus into the subacromial space resulted in erosion of the greater tuberosity (femoralization), and subsequent morphological changes to the coracoacromial arch (acetabularization) (Fig. 7–1).3 Clinical manifestations included shoulder swelling, supraspinatus and infraspinatus atrophy (weak abduction and external rotation [ER]), as well as limited, incongruous glenohumeral motion with debilitating (at times progressive) pain. Based upon their clinical observations and intraoperative examinations while performing 26 arthroplasties, Neer and coauthors estimated that ~4% of patients with massive RC tears would develop this pathological situation if untreated.3 Neer et al hypothesized that the presence of two interdependent mechanisms, mechanical and nutritional, contributed to the cyclical process of RC destruction and arthropathy. Radiographic (fluoroscopy, arthrography) and electromyographic analyses of RC tears in patients have provided information to support the force couple theory.4,5 An imbalance in transverse forces between the subscapularis and posteroinferior cuff or coronal forces between the deltoid and supraspinatus would result in displeasing kinematics. Unstable shoulder kinematics would lead to further wear and accelerated disruption of transverse and coronal plane force couples (Fig. 7–2).4,5 Figure 7–1 When pathological changes in cuff tear arthropathy occur, the classic pattern of rotator cuff arthropathy involves the superior migration of an osteoporotic humeral head combined with erosion of the coracoacromial arch. From Neer CS, Craig EV, Fukuda H. Cuff tear arthropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983; 65: 1236. Adapted by permission. Because the outcomes from the treatment of massive RC tears with glenohumeral arthritis are highly variable, attempts have been made to categorize the severity of the RCA. Seebauer and colleagues retrospectively analyzed all institutional patients with RCA treated with conventional hemiarthroplasty. Based upon functional outcomes and radiographs, the authors proposed a biomechanical classification of the RC-deficient arthritic shoulder.6,7 The four subtypes (Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb) were distinguished by degree of superior migration from the center of humeral head rotation and the amount of instability of the center of rotation (see Chapter 6, Fig. 6–3). The proposed benefits of this classification include decision-making for appropriate implant selection, adjustment of reconstruction goals, and assessment of patient functional outcomes. Figure 7–2 The transverse force couple between the subscapularis anteriorly and the external rotators (infraspinatus, teres minor) posteriorly are evident on an axillary view diagram. These two forces balance and centralize (in conjunction with the coronal forces of the deltoid and supraspinatus) the humeral head to produce concavity compression with the glenoid. From Jensen KL, Williams GR, Russell IJ, Rockwood CA Jr. Current concepts review: rotator cuff arthropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999; 81: 1316. Adapted by permission. Patients with RCA are generally in their 7th decade or older and are usually women.8 In general, a long history of progressive pain, particularly at night is given by the patient. The dominant upper extremity is more commonly involved. Diminished active shoulder motion (abduction, ER) with stiffness during passive range of motion (ROM) exercises is noted. Atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles with variable degrees of abduction and ER weakness occur. Shoulder swelling may be present secondary to excessive fluid pressure in the subacromial bursa. Aspiration of this fluid may be blood tinged or bloody in appearance. Removal of this fluid combined with steroid and anesthetic injections may provide temporary relief; however, fluid reaccumulation is common.8–10 True anteroposterior (AP) and axillary lateral views may demonstrate the characteristic radiographic findings of RCA (Fig. 7–3),8–10 Although not necessary, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful in clinical scenarios where physical exam findings are ambiguous or difficult to interpret (i.e., secondary to pain).8 The main impetus for surgical management of RCA is unremitting, progressive pain recalcitrant to nonoperative measures such as rest, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, corticosteroid injections, ROM exercises, fluid aspiration, and oral analgesics.8–10 A denervated or weakened anterior deltoid (less than antigravity strength), incompetent coracoacromial arch, and active or suspected sepsis all preclude implant arthroplasty as a treatment option.9 Figure 7–3 An anteroposterior radiograph demonstrates superior humeral head migration with rounding of the greater tuberosity (femoralization) and erosion of the coracoacromial arch (acetabularization). RCA, as a distinct endpoint along the continuum of glenohumeral degeneration, presents a unique operative challenge to the surgeon. The historical failure of total shoulder arthroplasty with glenoid component loosening, secondary to abnormal shoulder kinematics, precludes its use. Previous alternative attempts at surgical correction for improvements in pain relief, stability, and increased motion with constrained and semiconstrained devices have provided marginal results with unacceptable complication rates.8–10 Advances in implant design, instrumentation, and surgical technique have propelled further interest in the utilization of these devices, but long-term follow-up is lacking. Short-term results, though promising, still present unacceptable complication rates.10 The treatment goals of CTA are similar to those in standard degenerative (osteoarthritis) and inflammatory conditions (rheumatoid arthritis): shoulder arthroplasty should provide pain relief, restore glenohumeral stability, and improve functional motion (i.e., for activities of daily living). Based upon the severity of the arthropathy, the concept of “limited-goals” surgery may be appropriate when evaluating these patients.11 A current review of the literature indicates that the unconstrained implant (i.e., hemiarthroplasty) design has remained a viable alternative in the treatment of RCA. Utilizing the standard deltopectoral approach, Arntz, Jackins, and Matsen12 reported their experience with the Neer II prosthesis in the treatment of 19 patients (21 shoulders) over a 9-year period (1978 to 1987). Eighteen shoulders were available for review at a follow-up range of 25 to 122 months. Notably, pain diminished from “marked or disabling” in 14 shoulders to “none or slight” in 10, and “pain with unusual activity” in 4. Active forward elevation improved on average from 66 degrees preoperatively to 109 degrees postoperatively. Hemiarthroplasties were performed only in those patients with a functionally intact coracoacromial arch.12 Pollock et al13 in 1992 compared hemiarthroplasty versus total shoulder arthroplasty in 30 shoulders with RC tears. Thirteen shoulders at the time of surgery demonstrated massive irreparable RC tears and were subsequently treated with hemiarthroplasty and cuff débridement. All 12 patients (13 shoulders) reported little or no pain and displayed an average increase of 44 degrees of active forward elevation (average: 64 to 108 degrees) at 41 months postoperatively. In 1996, Williams and Rockwood14 reported their results in 20 patients (21 shoulders, average follow-up: 4 years) with irreparable RC tears and glenohumeral arthritis treated with humeral head replacement. Twelve shoulders demonstrated no pain, six were mildly painful, and three were moderately painful. The authors emphasized the need to preserve the coracoacromial ligament if present, and to alter humeral head size to obtain appropriate soft tissue balancing. In the presence of an incompetent coracoacromial arch, some authors have advocated augmentation with iliac crest bone graft or placement of bone from the resected humeral head in the area of the superior glenoid. Such techniques have resulted in noted improvements in pain relief.8 Recently, Hockman et al15

Classification

History and Physical Exam

Imaging

Surgical Treatment

Indications

Contraindications

Treatment Options

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree