Hemangiomas and Other Vascular Tumors of Infancy

Denise W. Metry

The most common tumors of infancy are benign vascular lesions. Before 1982, the term “hemangioma” was used to encompass a wide range of vascular growths, independent of clinical manifestations, natural history, or embryologic origin. Subsequently, Mulliken and Glowacki proposed the first biologic classification for vascular birthmarks. Their landmark article was the first to distinguish a hemangioma, characterized by a growth phase during infancy and an involutional phase during childhood, from a vascular malformation, a structural anomaly derived from arteries, veins, or lymphatics. In 1997, this classification was broadened to include two additional vascular entities: kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) and tufted angioma (TA). Box 316.1 presents the revised classification system.

In most cases, the correct classification of a vascular birthmark can be made based on history and clinical evaluation alone. For challenging lesions, imaging (most commonly magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) may be a helpful diagnostic tool. However, one must emphasize that if any question of malignancy exists, obtaining a tissue biopsy is imperative. Rarely, malignant tumors such as infantile fibrosarcoma can mimic benign vascular tumors and generally cannot be differentiated on the basis of imaging studies alone.

HEMANGIOMAS OF INFANCY

Epidemiology

Hemangiomas of infancy (HOI) are the most common tumors of childhood, estimated to occur in as many as 10% of infants.

The several known risk factors for their development are female gender (in at least a 3 to 5:1 female-to-male ratio), prematurity (low gestational age and/or weight), and white ethnicity. For reasons unknown, more than 60% of HOI are located on the head and neck, although they may develop anywhere in the skin and/or viscera. Most HOI are inherited sporadically, although autosomal dominant transmission has been reported in a few families.

The several known risk factors for their development are female gender (in at least a 3 to 5:1 female-to-male ratio), prematurity (low gestational age and/or weight), and white ethnicity. For reasons unknown, more than 60% of HOI are located on the head and neck, although they may develop anywhere in the skin and/or viscera. Most HOI are inherited sporadically, although autosomal dominant transmission has been reported in a few families.

BOX 316.1 Classification of Vascular Birthmarks

Vascular Tumors

Hemangiomas of infancy (HOI)

Localized, segmental, multifocal

Visceral hemangiomas

Multiple (five or more)

Significance in terms of organ involvement: liver >gastrointestinal >brain

Developmental anomalies

PHACE(S) syndrome (posterior fossa malformations, HOI, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta/cardiac defects, eye anomalies, sternal clefting/supraumbilical raphe)

Other: spinal dysraphism, genitourinary and anorectal anomalies

Other Vascular Tumors

“Congenital” hemangiomas

Rapidly involuting

Noninvoluting

Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma

Tufted angioma

Malignant tumors (e.g., infantile fibrosarcoma)

Vascular Malformations

Pathogenesis

Although the life cycle of hemangiomas is known to result from an imbalance between proliferative and apoptotic angiogenic factors, their precise origin remains elusive. Additional information concerning the origin of hemangiomas is presented in Box 316.2.

Clinical Features

Most HOI are not present at birth, but they become visible in the first few weeks to months of life. Early lesions may be subtle and mistaken by caregivers as a “scratch” or “bruise.” A telangiectatic patch surrounded by a vasoconstricted halo also is a typical early presentation. Proliferation of HOI subsequently occurs for approximately 6 to 18 months until a plateau phase is reached, and then involution begins. Involution is a slow process, which occurs over the course of 2 to 12 years at an estimated rate of 10% per year, leading to the following often-quoted percentages of complete HOI involution: 50% of children by age 5 years, 70% by age 7 years, and 90% by age 9 years.

HOI most commonly are superficial in presentation and less commonly are deep or combined. Superficial HOI are raised, bright-red papules, nodules, or plaques (Fig. 316.1), whereas deep HOI are soft, flesh-colored nodules or tumors that may show a bluish hue and/or central telangiectasias (Fig. 316.2). Occasionally, deep HOI are not recognized until several months after birth as a result of their sometimes subtle appearance. The historical, yet still commonly used, descriptors “strawberry” and “cavernous” should be discarded because they incorrectly imply that superficial and deep HOI are behaviorally and histologically distinct. Involution of superficial HOI manifests as a change of color from bright red to darker red, and grayish discoloration often is noted centrally as the tumors soften and flatten. Deep HOI undergo involution as do their superficial counterparts, although such changes generally are not visible clinically.

BOX 316.2 Origin of Hemangiomas

Recent evidence points to shared immunoreactivity between hemangioma tissue and several placental vascular-specific antigens, an interesting discovery because a greater than 20% incidence of hemangiomas of infancy (HOI) exists among mothers who undergo chorionic villous sampling. However, HOI are not simply a result of ectopic placental tissue, because they do not demonstrate placental villous architecture on histopathology, nor do they express known trophoblastic placental markers. Researchers have postulated that cells of placental origin may embolize to receptive fetal tissues during gestation. Recently, an immunohistochemical stain (GLUT-1) was recognized as a specific marker for HOI in all growth phases. GLUT-1 is a glucose transporter normally expressed in blood-tissue barriers, but not normal skin. Positive staining for GLUT-1 will occur only with HOI and not with any other vascular tumor or malformation.

Risks of Scarring

When discussing the prognosis for HOI, one must recognize that complete involution eventuates in normal-appearing skin in only half of the cases. Thus, explaining to a caregiver that

HOI will “go away” is not always accurate. Potential residual damage includes fibrofatty tissue (especially with very raised and/or pedunculated, superficial HOI), atrophy, yellowish discoloration, and/or telangiectasias (Fig. 316.3). Locations especially at risk for a suboptimal cosmetic outcome are the lip (particularly when HOI cross the vermilion border) and the cartilaginous regions of the ear and nose (Fig. 316.4). Ulceration, the most common overall complication of HOI, also inevitably results in scarring in addition to potential infection, bleeding, and pain (Fig. 316.5). Ulceration generally occurs during the proliferative phase in locations subject to trauma, especially the perineum and lip. The precise cause of ulcer development is unknown; however, given the characteristic locations, maceration and frictional stress are probable contributing factors.

HOI will “go away” is not always accurate. Potential residual damage includes fibrofatty tissue (especially with very raised and/or pedunculated, superficial HOI), atrophy, yellowish discoloration, and/or telangiectasias (Fig. 316.3). Locations especially at risk for a suboptimal cosmetic outcome are the lip (particularly when HOI cross the vermilion border) and the cartilaginous regions of the ear and nose (Fig. 316.4). Ulceration, the most common overall complication of HOI, also inevitably results in scarring in addition to potential infection, bleeding, and pain (Fig. 316.5). Ulceration generally occurs during the proliferative phase in locations subject to trauma, especially the perineum and lip. The precise cause of ulcer development is unknown; however, given the characteristic locations, maceration and frictional stress are probable contributing factors.

Morphology and Complications

Although most HOI remain inconsequential, some may cause or be associated with significant complications. The clinical appearance of a lesion often provides an important clue to identifying worrisome cases. A recently developed classification system divides HOI into localized, segmental, or multifocal types, based on morphology.

Localized HOI, by far the most common, are defined as papules or nodules that appear to arise from a single focal point and demonstrate clear spatial containment (see Fig. 316.1). Localized lesions are not random in distribution but occur near lines of mesenchymal or mesenchymal-ectodermal embryonic fusion. Furthermore, most (more than 60%) localized HOI occur within a relatively small area of the central face, of which the midcheek, lateral portion of the upper lip, and upper eyelid are the most common locations.

FIGURE 316.4. Superficial hemangioma of infancy of the nose in a patient at risk for permanent disfigurement. |

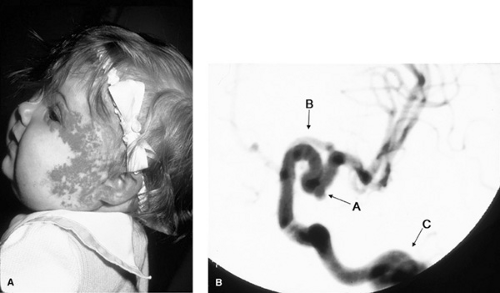

Segmental HOI are plaque-like in morphology and show a linear and/or geographic pattern over a specific cutaneous territory (Fig. 316.6A). In comparison with localized HOI, segmental lesions are much more likely to be associated with

complications such as ulceration and developmental defects to require more intensive and prolonged therapy, and to have a poorer overall outcome. Although speculative, HOI morphology and potential complications may reflect the timing of HOI etiopathogenesis, with earlier events (between 6 and 8 weeks’ gestation) resulting in segmental lesions and later events in localized ones.

complications such as ulceration and developmental defects to require more intensive and prolonged therapy, and to have a poorer overall outcome. Although speculative, HOI morphology and potential complications may reflect the timing of HOI etiopathogenesis, with earlier events (between 6 and 8 weeks’ gestation) resulting in segmental lesions and later events in localized ones.

Multiple HOI, generally defined as five or more lesions, usually are limited to the skin but rarely can be associated with symptomatic visceral hemangiomatosis.

Vital Organ Compromise

Both morphology and location must be considered when deciding whether HOI may result in compromise of a vital organ. Best known is the potential for periorbital HOI to impair visual development. Upper eyelid HOI are of greatest concern because of the potential for gravity-induced ptosis (Fig. 316.7), although lesions of the lower eyelid also may prove problematic. Amblyopia can occur from stimulus deprivation when the visual axis is directly obstructed, or astigmatism can result from insidious distortion of the growing cornea. Evaluation by an experienced ophthalmologist is necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree