Closed Head Injury

Hamish A. Kerr, MD, MSc, Primary Care Sports Medicine Fellowship, Division Internal Medicine/Pediatrics, Albany Medical College, 724 Watervliet-Shaker Road, Latham, NY 12110, USA. E-mail address: kerrh@mail.amc.edu

Keywords

Concussion

Intracranial hemorrhage

Skull fracture

Facial fracture

Eye injuries

Scalp laceration

Pinna hematoma

Epidemiology of closed head injury

It has been estimated that 3% of all sport-related injuries are to the head,1 with an increasing percentage seen with age:

• 2.8% sports-related injuries in children younger than 10 years

• 3.7% of sports-related injuries in 10- to 14-year old children

Head injuries are 1 of the top 4 body areas injured (ankle, knee, shoulder, head) in contact sports such as rugby.2,3 In soccer, estimates suggest 4% to 22% of all injuries are to the head.4,5 They are common in winter sports,6 although the introduction of helmets for skiing and snowboarding has certainly diminished the risk of more severe head injury.7 Other helmeted sports such as football, ice hockey and men’s lacrosse still have a risk of functional brain injury despite the protective equipment.8,9 Protective equipment is also recommended in projectile sports such as baseball and cricket for certain positions are at risk of being hit by the ball.7 Baseball causes the most eye injuries in 5- to 15-year-old children in the United States, while in 25- to 65-year-olds, racquet sports cause the most eye injuries.10–12 Prevention is possible with appropriate eyewear.13

Closed-head injuries vary in severity from minor scrapes, lacerations, and abrasions that are inherent to almost every game of rugby, to the most severe brain injuries including intracranial hemorrhage, which has a significant mortality rate.14,15 Differentiating the minor from the most severe can be difficult, may not immediately be apparent to even the highly trained and experienced physician, and often requires longitudinal reassessment to identify the athlete who is deteriorating.

Closed-head injury initial evaluation

Fieldside evaluation of a witnessed closed-head injury begins with the assumption of cervical spine injury and possible spinal cord injury in any athlete knocked unconscious.14,16–19 Airway, breathing, and circulation must be assessed before evaluation of head itself. If there is a dilated pupil, endotracheal intubation can be considered before transport on a spinal board.

Although some injuries such as a bleeding laceration may be obvious immediately, brain injury, and concussion in particular, may take careful examination to exclude. In the absence of a loss of consciousness, an athlete should be removed from the field of play and assessed on the sideline. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and Maddocks questions can help assess consciousness and orientation and are included in the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool Version 2 (SCAT II) that was developed for this purpose.20–23 Deterioration in scoring on serial SCAT II assessment, scoring greater than13 on the GCS, or any focal neurologic finding should prompt urgent transport to a trauma center.14,24

Soft tissue trauma: scalp and facial lacerations

Lacerations should be irrigated with sterile saline and explored for foreign bodies or underlying damage. Pressure should be applied to control bleeding. Sutures are required to close the wound. Tetanus prophylaxis is advised. Simple lacerations less than 4 cm that are not at points of high skin tension are recommended to be closed by a tissue adhesive, such as Dermabond (Ethicon, Inc. Menlo Park, CA),25 which showed superior cosmetic outcome without increased complications in a randomized trial versus sutures.

Deep absorbable sutures are necessary if there is separation of deep tissue. With lacerations over an area of dynamic muscle contraction (eg, forehead, perioral, or over the mandible), initial subcutaneous sutures can decrease wound tension.25,26 An invisible soft tissue surface or scalp laceration can be closed with 5-0 sutures,27 while facial lacerations should be closed with 7-0 monofilament nylon sutures. Lacerations involving the lacrimal apparatus, parotid gland, facial nerve (facial droop or asymmetry), or anatomic borders should be referred, as should those across structural or functional borders such as vermilion border of lip, eyelid, nasal alar rims, or helical rims of ear, which require great precision in the repair to prevent poor cosmetic results.

Soft tissue trauma: pinna hematoma

Trauma to the pinna is relatively common in collision sports where participants do not wear helmets. Rugby is perhaps the best example; pinna hematomas are the rugby team physician’s bread and butter. Hematomas are best drained in the days after the injury,; then silicone mold material should be placed in the same area to prevent reaccumulation.28–30 Rugby players can help prevent pinna hematomas by taping their ears or by wearing a scrum cap.31

Facial trauma: eye injury

Evaluation of a possible eye injury (not always possible fieldside) should include32

Eye injury: vision-threatening injuries

Injuries to the globe, retrobulbar hemorrhage, traumatic optic neuropathy, and eyelid laceration can all result in loss of vision if not identified and managed appropriately.34 A relative afferent papillary defect (RAPD) is a sensitive indicator of visual impairment suggesting asymmetrical damage to retina, optic nerve, chiasm, or optic tract.

Globe Rupture

Globe rupture is differentiated into open, with a full-thickness tear through cornea, and sclera and closed, without a full-thickness tear. Globe rupture is a common cause of blindness after trauma; it requires a high index of suspicion, as it is not always obvious.35 Signs of globe rupture include decreased visual acuity, a severe subconjunctival hemorrhage involving all quadrants of the conjunctiva, and limited external ocular muscle movement. In addition, globe collapse may be seen manifested by low intraocular pressure (IOP), extruded eye contents, and a hyphema if open. In this circumstance, applied pressure can cause further expulsion of globe if there is an open rupture, and this should be avoided at all cost. A shield should be taped over the eye and the patient transported to a facility where surgery can be accomplished within 24 hours.

Retrobulbar Hemorrhage

This condition is a compartment syndrome of the eye, with irreversible damage occurring after 60 minutes of ischemia.36 Hemorrhage and edema in the orbit lead to an increase in IOP, compression of the blood supply, and ischemia of optic nerve and retina. Signs of retrobulbar hemorrhage include proptosis, loss of vision, pain, and an absent RAPD or dilated pupil. The condition requires relief of the pressure with a lateral canthotomy and inferior cantholysis, then ultimately surgical decompression.

Eyelid Laceration

Eyelid laceration may be a sign of a more serious ocular injury. An assessment for a penetrating globe injury or foreign body should be conducted. If the eyelid cannot close, the cornea dries, so even small eyelid lacerations can threaten vision loss. Medial lacerations can damage the lacrimal system, and upper eyelid laceration can damage the levator palpebrae, resulting in ptosis.27 Eyelid lacerations should be treated with generous antibiotic ointment application, covering with a wet gauze, and then surgical repair.

Facial trauma: dental injuries

An avulsed tooth should be replaced in its socket whenever possible, and the athlete instructed to bite down on some gauze to keep it in place. If replacement is not possible, the tooth should be placed in Hank’s solution to preserve it.37–40 The tooth should be handled only by the crown and gently washed if not clean. Reimplantation within 30 minutes results in a 90% success rate, saving the tooth, so an immediate dental referral is essential. A delay greater than 2 hours decreases the success rate to only a 5% chance.41 Mouth guards are a key prevention strategy for dental injuries.42

Facial trauma: facial fracture

Facial fractures account for 4% to 18% of all sports injuries, and sports are responsible for 6% to 33% of all facial bone fractures.43–45 Midface and mandibular fractures may threaten the airway or can cause a lot of bleeding. Orbital or zygomatic fractures can threaten vision.

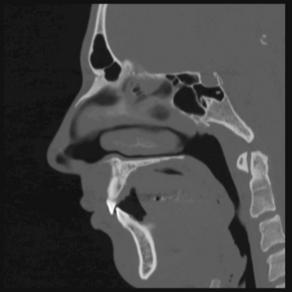

Facial Fracture: Orbital Blowout Fracture

Orbital blowout fractures generally result from blunt trauma to eye, and then collapse of the inferior or medial orbital wall. The collapse may entrap the medial and lateral rectus muscles, thus reducing external ocular muscle movement on examination. Orbital blowout fractures are more common than globe rupture, as the collapse of the inferior orbital wall helps decrease the amount of pressure absorbed by the globe.46 Physical examination often reveals diplopia, enopthalmos, and infraorbital hypoesthesia secondary to damage to the infraorbital nerve.47,48 Computed tomography (CT) scan imaging can exclude strangulation of the extraocular muscle, which can otherwise cause necrosis if not identified.

Superior orbital fissure syndrome occurs when there is compression of cranial nerves 3 or 4 as they pass through the superior orbital fissure. Typically, the increased IOP will limit external ocular muscle movement and cause paresthesiae of the forehead and brow. This syndrome needs emergency surgery (Fig. 1).49

Facial Fracture: Zygomatic Fractures

Zygomatic anatomy includes the cheekbone, orbit, and orbital rim. The zygomatic bone acts as an attachment for the masseter muscle and the outer facial frame. Zygomatic fracture therefore affects vision, jaw function, and the width of the face. Mechanism of injury is usually blunt trauma, presenting with flattening of the cheekbone. There may also be subconjunctival hemorrhage, periorbital ecchymosis, a palpable step-off in the upper outer or inferior orbital rim, emphysema, trismus, malposition of the globe, and diplopia. Fracture management should include operative fixation within 2 weeks50,51 for displaced or comminuted fractures (Fig. 2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree