3 Hand

3.1 Introduction

Injuries to the hand play a major role both in sports and in occupations. The hand is among the most frequently injured parts of the body. Although the injuries themselves are rarely life threatening, the loss of sensory and motor capabilities severely compromises a patient’s well-being. Diagnosis of hand injuries can be difficult due to the close proximity of many anatomical structures, and particularly since symptoms can be subtle. This is especially true of the wrist. Differences in the motion of the carpal bones make the wrist subject to a wide range of injuries from acute and chronic stresses. Thorough familiarity with the functional anatomy and detailed knowledge of the patterns of motion in specific sports are required to make a precise diagnosis.

The primary functions of the hand are sensation and grasping. Sensation is especially crucial on the radial aspect of the index finger and on the ulnar aspect of the thumb, the surfaces primarily involved in grasping, feeling, and holding. Mobility of the hand and the entire upper extremity is important for grasping. The hand must be able to reach the mouth. The arm provides a balanced motor system that permits both forceful and fine coordinated motions.

Evolutionary specialization of the thumb as an opposable digit provides humans with exceptional motor abilities in the upper extremities. This specialization makes the thumb the most important digit of the hand; preservation of its function is one of the highest-priority goals in therapy.

3.2 Clinical Examination

Patient History

Clinical examination begins with systematically taking a history of all personal and medical data. The patient’s age, occupation, and leisure and athletic activities often influence the indications for hand surgery, as do comorbidities, social background, and emotional disorders. The patient’s general condition as well as cardiovascular problems, diabetes, coagulopathy and convulsive disorders can significantly influence decisions pertaining to surgical intervention. Chronic symptoms require a thorough history. The patient should discribe any previous illnesses or earlier injuries, and indicate the duration of present symptoms. Inquire when symptoms occur and whether they fluctuate over time. Have the patient describe patterns of pain and behavior of the hand in motion and under stress. A thorough history will provide sufficient information for a tentative diagnosis. For example, altered sensation and weakness in the index and middle fingers accompanied by nighttime paresthesia is often characteristic of carpal tunnel syndrome. Sudden, occasionally painful, snapping over the metacarpal heads when flexing and extending a finger is a typical sign of trigger finger. When evaluating chronic symptoms, inquire about previous periods of occupational disability. It is also important to determine which previous interventions were successful in alleviating symptoms.

In acute trauma, always document the time, site, and description of the accident. Record the type of injury. Differentiate between cuts, crush injuries, saw accidents, injuries from chemical action or burns, bite wounds, and closed trauma. This information can be important for determining subsequent diagnostic strategy. Do not underestimate the significance of seemingly minor injuries. It is important to determine the precise time of the accident since this has therapeutic consequences. This applies particularly to replantation and treatment of open wounds, but also to primary repair of a torn tendon, which will usually only be effective if performed within the first 10–14 days. The object that caused the injury should be known; this is important in evaluating the danger of infection in open wounds.

Often, the clinical suspicion developed while obtaining the history only requires confirmation in further diagnostic studies. If the patient has already consulted another physician, it is important to obtain precise information about prior treatment and the course of therapy to date.

Observation

General Observation

It is best to follow a routine when examing the patient, especially when preparing a medical opinion. Inspection begins as the patient enters the examining room. Valuable information about pain and compensatory posture can be obtained by observing the patient’s spontaneous behavior. Compare both sides when inspecting the patient, and include the entire upper extremity. Document the shape and posture of the hand first. The shape can be altered by generalized or localized swelling, congenital or acquired deformities involving position, contractures, and muscle atrophy. Localized swelling may be found with inflammation, tumors, after injury of the capsular ligaments, and in fractures. Ganglia originating either at the tendons, synovial lining, or the joints (Figs. 3.1) can cause swelling. Muscle atrophy occurs after prolonged periods of inactivity or as a sequelae of compressive neuropathy (thenar atrophy after prolonged compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel). Axial deformities suggest a fracture or dislocation; limp flexion of the distal phalanx of a finger suggests injury to an extensor tendon. Next, the skin is inspected. The color of the skin provides information on the current state of vascular supply to the hand. Color changes may occur as a result of bacterial infection (with localized hyperemia and erythema). They may also occur with systemic or metabolic disorders (shiny atrophic skin in progressive scleroderma; hyperpgimentation of the palmar furrows in Addison disease; palmar erythema in chronic disorders involving hyperglobulinemia, such as cirrhosis of the liver). Skin color may also change with inflammatory joint disorders (spotted erythema and cyanosis in rheumatoid arthritis).

Fig. 3.1 Ganglion on the extensor side of the wrist.

The calluses on the palmar surface provide clues about occupation and physical exertion. Dominance of the hand (right or left-handed patient) should be taken into consideration. Inability to perspire is a sign of impaired nerve function in the hand or finger, particularly when clearly demarcated from the normal adjacent skin. Dry and scaly areas of skin are a sign of loss of nerve function in the hand or finger. The appearance of the fingernails (i.e., deformation, change in color, or change in consistency) can provide information about systemic disorders or metal intoxication. Hollow nails suggest iron-deficiency anemia; “half and half” nails suggest renal insufficiency and cirrhosis of the liver. Hourglass nails, often together with clubbed fingers, are seen in bronchial carcinoma and other lung disorders, cirrhosis of the liver, regional enteritis, and cyanotic heart defects. Mees stripes are seen with thallium and arsenic poisoning. In postmenopausal women, posterolateral swelling is often observed in the distal interphalangeal joint. This is known as Heberden’s nodes and can present as a painful flexion contracture of the distal joint. Arthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint, referred to as Bouchard’s nodes, is rare in comparison.

Fig. 3.2 Rheumatic hand with swan-neck deformity of the index finger, boutonnière deformity of the middle finger, and ulnar deviation of the long fingers.

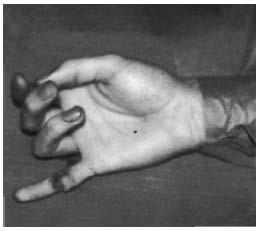

In addition to swelling of individual fingers and finger joints, symmetric swelling at the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints can be observed in rheumatoid arthritis. Often, these joints (especially the metacarpophalangeal joints of the index and long fingers) are the first location in which the chronic inflammatory disorder will manifest itself. This can be accompanied by transient joint effusions and tenosynovitis. Women are most frequently affected (women:men=3:1). Patients complain of typical morning stiffness in the affected joints, and pain during motion or palpation. Increasing destruction of the capsular ligaments, tendons, and articular surfaces in the further course of the disease can produce characteristic finger deformities. These include:

– Swan-neck flexion deformity of the metacarpophalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints with an overextended proximal interphalangeal joint (Figs. 3.2).

– Boutonnière deformity with flexion in the proximal interphalangeal joints and extension in the distal interphalangeal joint (Figs. 3.2).

– Deformity of the thumb with 90° flexion in the metacarpophalangeal joint and 90° hyperextension in the distal joint.

– Ulnar deviation of the fingers (Figs. 3.2).

Examination of a severely injured hand is difficult yet imperative. Often inspection of visible injuries permits an estimation of the degree of injury and subsequent diagnostic procedure. The location of the injury provides some information about the damaged structures. Palmar lesions primarily involve flexor tendons and neurovascular structures; dorsal lesions usually involve extensor tendons, bones, and joints. The position of injured fingers can be a sign of tendon injuries. Axial and rotational defects provide information about fractures and joint injuries, such as dislocations and tendon tears. In complex injuries, neurovascular bundles and tendon stumps can be inspected. It is also important to evaluate the degree of contamination of the hand (Figs. 3.3 and 3.4).

Fig. 3.3 Flexor tendon injury.

Fig. 3.4 Circular-saw injury.

Fig. 3.5 Syndactyly of the middle and ring fingers.

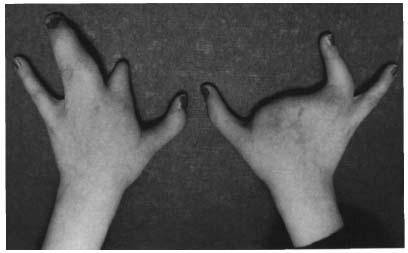

Deformities

Congenital anomalies of the upper extremity are rare and are only found in one of 600 newborns. Approximately 10% of this number are estimated to be severe functional deformities. Polydactyly is the most frequent deformity of the hand, followed by syndactyly. Deformities can be caused by hereditary diseases such as trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) and exogenous factors such as thalidomide (Figs. 3.5 and 3.6).

Fig. 3.6 Bilateral cleft hands.

Fig. 3.7 Palpation of the scaphoid.

Palpation complements the impression gained by inspection. Systematic palpation of the hand includes evaluation of soft tissue, bone, and joints. Turgor and perspiration of the hand are also assessed. The skin of the palm of the hand is significantly thicker than that of the dorsal hand. Numerous fibers radiate from the palmar aponeurosis as retinacula into the skin of the hollow of the hand, firmly connecting it to the aponeurosis. This makes it possible to firmly grip objects without the skin separating from the subcutaneous tissue. Evaluate the skin’s surface texture (smooth or rough; dry or moist), mobility, and temperature. Swelling may be due to effusion or changes in the soft tissue or bone; evaluate swelling for consistency (soft, hardened, or fluctuant). Knotty changes or changes over a wide area detected in the connective tissue on the hollow of the hand can suggest a Dupuytren’s contracture. Tender areas should be precisely localized; check for radiating pain. Nodular thickening in the annular ligaments that causes a snapping sound and transient locking during flexion or extension suggest a trigger finger. Abrasion injuries are examined by evaluating restoration of capillary flow.

Palpation should not be limited to the hand. The examination should include the elbow, shoulder, and cervical spine, particularly when pain radiates into the forearm. Be particularly alert to localized tenderness resulting from overuse (medial and lateral humeral epicondylitis) and peripheral nerve compression syndromes, including supinator syndrome, pronator teres syndrome, and cubital tunnel syndrome. Compare results with the contralateral side to confirm findings.

The major landmarks for palpation of the hand include:

Radial styloid. This is an important orientation point for palpation of the wrist. Tenderness to palpation over this area can suggest tendinitis at the insertion of the brachioradialis as can occasionally occur in athletes whose sport involves backhand motions. Isometric muscle tensing increases the pain.

Fig. 3.8 Palpation of the trapezium and the first metacarpal.

Anatomical snuffbox and scaphoid. The anatomical snuffbox is located on the dorsum of the wrist, distal to the radial styloid. It is readily discernible with the wrist in slight ulnar deviation and the thumb extended and abducted. This hollow is bounded by the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis on the radial aspect, and the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus on the ulnar aspect. The scaphoid is palpable on the floor of the hollow (Figs. 3.7). Pain to palpation in this area, together with pain during radial deviation, suggests injury to the scaphoid. Due to the strong forces acting on it, this is the most frequently fractured carpal bone.

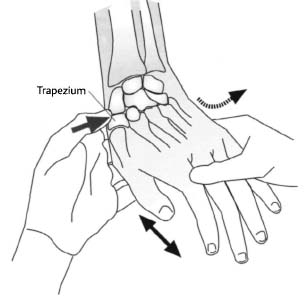

Trapezium and base of the first metacarpal. Together with the base of the first metacarpal, the trapezium forms the joint of the base of the thumb. The trapezium is distal to the snuffbox and is palpable with the thumb in flexion and extension (Figs. 3.8). The joint of the base of the thumb has a slight degree of physiologic dorsopalmar mobility. Traumatic changes such as Bennett or Rolando fractures and degenerative changes such as osteoarthritis will be painful to palpation in this area. A rupture of the palmar capsule of the joint results in abnormal motion with respect to the base of the second metacarpal.

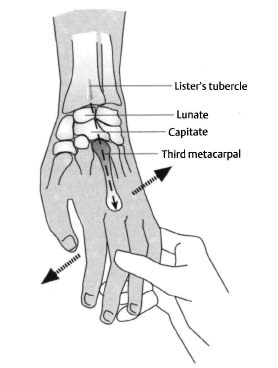

Capitate and base of the second metacarpal. The capitate is palpable proximal to the largest and most important of all metacarpal bases, the third metacarpal.

Lunate and Lister’s tubercle. The lunate is palpable in flexion and extension immediately distal to Lister’s tubercle, which lies on the dorsal aspect of the distal radius directly in line with the third metacarpal (Figs. 3.9). The lunate can be damaged by dislocation, avascular necrosis, and fractures. In these cases, palpation will usually reveal localized tenderness, and moving the wrist will be painful. The tendon of the extensor carpi radialis brevis covers the lunate together with the capitate and the base of the third metacarpal.

Fig. 3.9 Linear alignment of Lister’s tubercle, lunate and capitate bones, and third metacarpal.

Fig. 3.10 Palpation of the pisiform.

Fig. 3.11 Palpation of Guyon’s canal.

Ulnar styloid. The ulnar styloid is another important landmark for palpation of the wrist. Pain in this area can be attributable to tendinitis at the insertion of the flexor carpi ulnaris. The tendon of this muscle is ulnar to the tendon of the palmaris longus and palpable if the wrist is extended or dorsiflexed against resistance with the fist clenched. In rheumatoid arthritis, painful swelling can occasionally be demonstrated here. The ulnar styloid is frequently injured in falls and crush injuries.

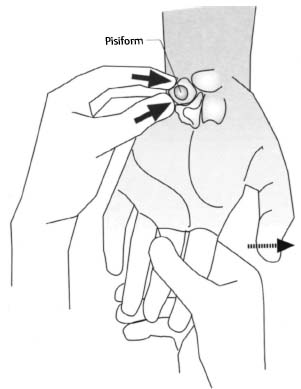

Triquetrum and pisiform. The triquetrum lies distal to the styloid. It is palpable under the pisiform when the wrist is in radial deviation. The pisiform is palpable as a sesamoid bone on the distal flexor carpi ulnaris (Figs. 3.10). The flexor retinaculum, the extensor retinaculum, the tendons of the abductor digiti minimi, and the fibrous complex of the ulnocarpal compartment insert on the pisiform.

Fig. 3.12 Anatomy of Guyon’s canal.

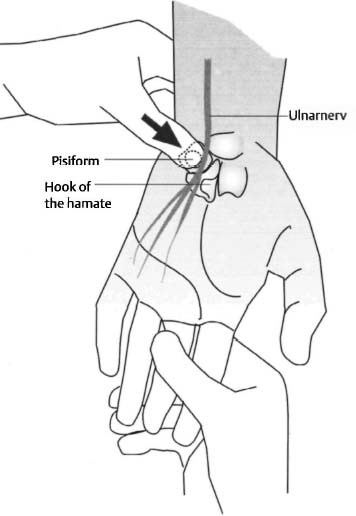

Hamate and Guyon’s Canal. The hamate may be difficult to palpate because it lies in a deep plane and is covered by a cushion of soft tissue. The prominent hook of the hamate and the pisiform form the lateral boundary of Guyon’s canal, through which the ulnar artery and nerve pass (Figs. 3.11). The canal becomes clinically significant with compression of the nerve in acute and chronic trauma. Tumors can also cause nerve compression. Specific symptoms can vary significantly; complete or partial compression may be present depending on the cause, the anatomical position, and the pattern of the nerve branches. (Figs. 3.12.)

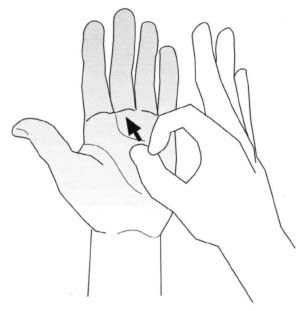

Palmaris longus. The tendon of the palmaris longus is best palpated with the wrist slightly flexed and the thumb and small finger opposed (Figs. 3.13). The tendon appears prominently on the palmar aspect of the wrist. It is distal and marks the palmar surface of the carpal tunnel. The palmaris longus is among those muscles that show the greatest variations and form, attachment, and bilateral symmetry. In approximately 12% of the population, the palmaris longus is absent. The tendon of this muscle is important as a graft for replacing injured finger flexor tendons.

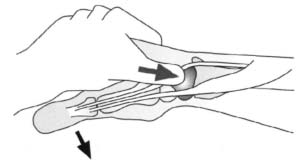

Carpal tunnel. The hook of the hamate on the ulnar side, the scaphoid tuberosity, and the trapezium on the radial side define the carpal tunnel. This tunnel contains the median nerve and the flexor tendons of the fingers that extend from the forearm into the hand. The transverse carpal ligament covers the tunnel. As in Guyon’s canal, various factors such as connective-tissue disorders with synovialitis, systemic diseases, trauma, and tumors can compress the nerve in the tunnel and affect sensory and motor function. Opposition of the thumb can be impaired by loss of function of the opponens when the thenar branch is affected. (Figs. 3.14).

Flexor carpi radialis. The tendon of the flexor carpi radialis is radial to the tendon of the palmaris longus and palpable in flexion with the fist clenched and the wrist in radial deviation (Figs. 3.15). This tendon crosses the scaphoid and inserts at the base of the second metacarpal.

Fig. 3.13 Palpation of the palmaris longus.

• Extrinsic extensor tendons First dorsal compartment. This compartment forms the palmar margin of the anatomical snuffbox. It contains the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus and the extensor pollicis brevis. These tendons can be distinguished as they leave the compartment by having the patient extend or abduct the thumb (Figs. 3.16). This region is affected in stenosing tenosynovitis (De Quervain) and because of the close proximity of the superficial branch of the radial nerve. De Quervain is caused by inflammatory swelling of the synovial lining of the compartment, which narrows the tunnel and causes pain during movement. Repetitive rotational motions in the wrist can contribute to this disorder. Paddlers and canoeists are among those frequently afflicted with the disorder. Pain in this region can also be caused by radial styloiditis, generally a tendon disorder involving the insertion of the brachioradialis.

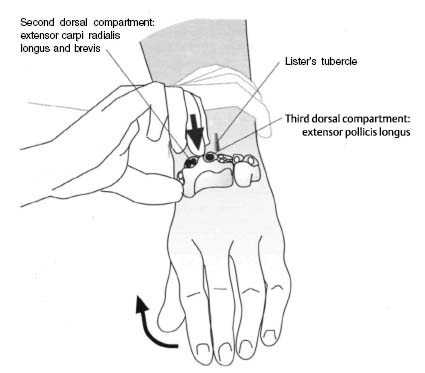

Second dorsal compartment. This compartment contains the tendons of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis. These tendons are palpable when the patient makes a fist. This causes the tendons to stand out on the radial side of the Lister tubercle (Figs. 3.17).

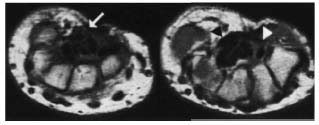

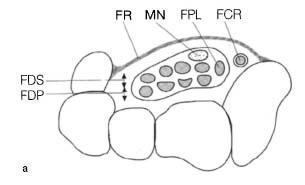

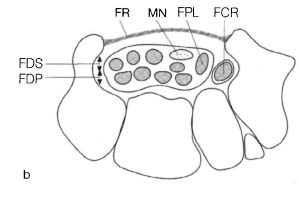

Fig. 3.14 Schematic cross-sectional anatomy of the carpal tunnel.

a Axial section at the inlet at the level of the pisiform.

b Axial section at the outlet at the level of the hook of the hamate. Abbrevations: FR = flexor retinaculum, FDS and FDP = tendons of the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus, FCR = flexor carpi radialis tendon, FPL = flexor pollicis longus tendon, MN = median nerve.

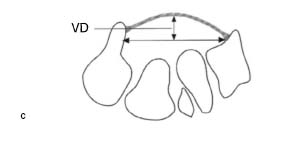

c Diagram for measuring the volar deviation (VD) of the flexor retinaculum. This is defined as the distance between the maximum protrusion of the flexor retinaculum and a line drawn between the trapezial tuberosity and the hook of the hamate.

Fig. 3.15 Palpation of the flexor carpi radialis tendon.

Fig. 3.16 Palpation of the first dorsal compartment.

Fig. 3.17 Palpation of the second dorsal compartment.

Fig. 3.18 Palpation of the third dorsal compartment.

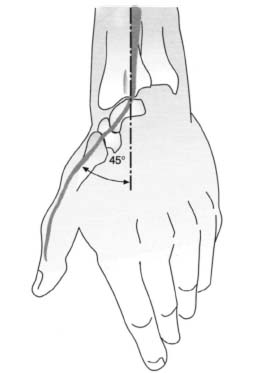

Third dorsal compartment. The tendon of the extensor pollicis longus can be palpated on the ulnar side of the Lister tubercle in the third dorsal compartment.

This tendon forms a 45° angle (Figs. 3.18). It continues on to the thumb, crossing the tendons of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis.

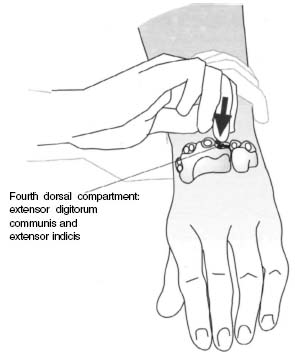

Fig. 3.19 Palpation of the fourth dorsal compartment.

Fig. 3.20 Palpation of the fifth dorsal compartment.

Fig. 3.21 Palpation of the sixth dorsal compartment.

Fourth dorsal compartment. The tendons of the extensor digitorum communis and extensor indicis lie in this compartment. They are not as accessible as the other extensor tendons, but each tendon should be palpated individually (Figs. 3.19). The tendon of the extensor muscle lies deeper; in rare cases it will have its own separate tunnel.

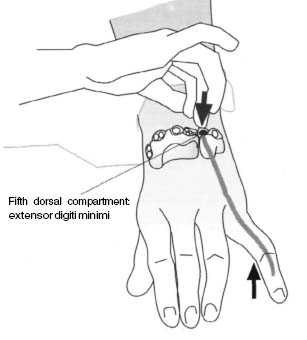

Fifth dorsal compartment. The extensor digiti minimi tendon will be palpable immediately lateral to the ulnar styloid when the patient rests the hand on the table and raises the little finger (Figs. 3.20). As with the extensor indicis tendon, the extensor tendon of the little finger can move independently of the other extensor tendons; this can be demonstrated by having the patient extend the little finger and index finger while flexing the other fingers. Because of its location immediately adjacent to the radioulnar joint, the extensor digiti minimi tendon can be injured in a posterior dislocation of the ulnar head.

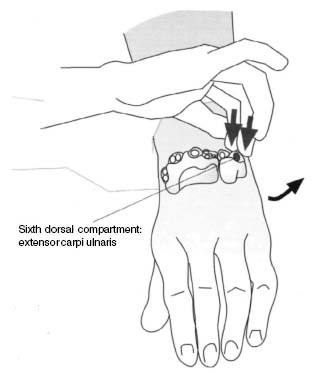

Sixth dorsal compartment. This compartment contains the tendon of the extensor carpi ulnaris. This tendon is palpable between the tip of the ulnar styloid and the base of the fifth metacarpal with the wrist extended and in ulnar deviation (Figs. 3.21). If the ulnar styloid is avulsed in a radial fracture, the tunnel can also tear, causing the tendon to dislocate over the ulnar styloid with an audible snapping noise when the wrist is pronated.

• Intrinsic extensor tendons

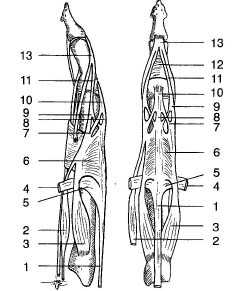

The tendons of the intrinsic muscles of the hand (the interossei and lumbricals) are difficult to palpate. They form a complex extensor apparatus of the finger (Fig. 3.22).

Thenar and hypothenar eminences. Palpate the ball of the thumb and little finger, and evaluate their size and consistency. Prolonged compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel can lead to atrophy of the thenar musculature. Compression of the ulnar nerve in or proximal to Guyon’s canal can lead to atrophy of the hypothenar eminence. Findings should always be compared with the contralateral hand.

Fig. 3.22 Anatomy of the extensor tendons of the fingers: (1) tendon of the extensor digitorum, (2) lumbrical, (3) interosseus, (4) deep transverse metacarpal ligament, (5) transverse part of the superficial intertendinous lamina, (6) intertendinous lamina (hood of the extensor expansion), (7) medial part of the interosseus tendon, (8) medial part of the extensor digitorum, (9) lateral part of the interosseus tendon, (10) intermediate band, (11) lateral band, (12) triangular ligament, (13) terminal tendon of the dorsal aponeurosis.

Palm. Structures within the palm are difficult to palpate because of the soft tissue covering them. In Dupuytren’s contracture, areas of knotty or cord-like thickening will be palpable in the palmar aponeurosis, particularly on the ulnar side over the fourth and fifth metacarpals. These areas can extend into the fingers. In addition to thin, tendon-like strands that do not show significant adhesions to the skin, thick cordlike and knotty structures with adhesions to subcutaneous tissue will be present. Pitting may also be present. Flexion contractures of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints with limited abduction of the fingers can occur.

Dorsum. In contrast to the flexor tendons, the extensor tendons on the dorsum of the hand are readily palpable, particularly at the heads of the metacarpals. The fourth and fifth metacarpals can be passively moved relatively easily, while the second and third metacarpals are securely anchored in the carpal region and allow little motion. Metacarpal fractures often occur in the neck region. Primary symptoms include swelling and tenderness to palpation. The fifth metacarpal is the most frequently fractured.

Fig. 3.23 Tear of the palmar plate.

Phalanges. The thinner soft-tissue envelope of the phalanges makes them more accessible to palpation. Document any deformities, swelling, or tenderness to palpation, especially in the joints. Swelling in the proximal interphalangeal joints that is tender to palpation is often a sign of disruption of the capsular ligaments, particularly in athletes (Figs. 3.23). Delayed or incorrect diagnosis and treatment of these injuries can lead to chronic swelling and impairment of function.

Fingertips. Infections of the hand can arise from minor injuries to the fingers and fingertips that are left untreated. Thorough palpation is required where infection is suspected. Even minor, apparently superficial, infections can progress proximally along the tendon sheaths. An infection in the little finger can spread through the tendon sheaths and the synovial lining of the wrist to the thumb, or vice versa, in a Ushaped pattern of inflammation. Palpation of the infected tendon is intensely painful. Chronic infections can lead to permanent loss of function in the hand and, under certain conditions, to life-threatening situations. Paronychia is the most frequent infection of the hand and usually occurs at the base of the fingernail. A distinction is made between a periungual felon (along the nail fold), a subungual felon (beneath the nail), and a subcutaneous felon that is very painful because of the tight connective tissue.

Assessing Range of Motion

To obtain an overview of hand function, evaluate various forms of grasping, the clenched fist, extension of all the fingers, abduction and adduction of the fingers, and opposition of the thumb. The patient should be able to touch each fingertip with the tip of the thumb. Always compare both hands. These simple tests can often provide important information about possible injuries, which can then be evaluated in more specific examinations. The precise active and passive ranges of motion of the hand and finger joints are determined separately for each joint; the respective measured arcs are recorded in degrees. These initial findings are documented and used as the basis of subsequent studies. The ranges of motion of the elbow, shoulder, and cervical spine should also be determined in preliminary tests.

The patient should be able to perform active motion without pain. The following ranges of motion are regarded as normal:

• Wrist

– Dorsal extension and palmar flexion 35°–60°/0°/50°–60°

– Radial deviation and ulnar deviation 20°/0°/40°

– Supination and pronation 90/°0/°90°

• Finger joints

– Metacarpophalangeal extension and flexion 10°–30/°0/°90°

– Proximal interphalangeal extension and flexion 0/°0/°100°

– Distal interphalangeal extension and flexion 0/°0/°90°

– Abduction and adduction 20/°0/°20°

• Thumbs

– Metacarpophalangeal extension and flexion 0/°0/°50°

– Interphalangeal extension and flexion 20/°0/°90°

– Abduction and adduction 45/°0/°0°

– Anteversion and retroversion 45/°0/°0°

Mobility of the wrist will vary according to the patient’s occupation, age, and sex. Factors influencing the range of motion include the joint contour, the capsular ligaments, and the musculature acting on the joint. Joint motion can be limited in active motion, passive motion, or both. Reversible limitations of normal wrist and finger motion are often the result of acute or chronic tenosynovitis and fibrous proliferation with intra-articular or periarticular adhesions. Permanent limitations result from destruction of the articular surface, fractures, and shortening of the capsular ligaments or tendons.

Fig. 3.24 Evaluation of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon.

Differences in active and passive ranges of motion, and changes in the range of motion according to the position of the joint, narrow the differential diagnosis. For example, equal limitations in the active and passive ranges of motion of a joint, regardless of the position of the joint, are a sign of shortening of the surrounding capsule and ligaments. An extension deficit in a proximal interphalangeal joint that does not change as the metacarpophalangeal joint moves is a sign of adhesion of a tendon at the level of the metacarpophalangeal joint. With an adhesion in the palm region, you can neutralize the resulting flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joint by passively flexing the metacarpophalangeal joint. Adhesions of the flexor tendons in the carpal tunnel only permit extension of the fingers when the wrist is in flexion. Adhesions of the extensor tendons in the forearm prevent flexion in the wrist when the patient makes a fist; adhesions of the flexor tendons prevent extension with the fingers extended. Impairment of active movement of only one finger is a sign of a tendon rupture or a neurologic lesion.

Specific Tests

Evaluating Flexor Tendon Function

Tendon injury must be excluded in any wound on the flexor side of the hand and finger. Always evaluate tendon function against resistance to distinguish partial tears from complete tears.

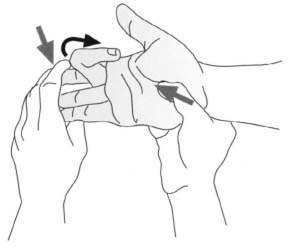

Flexor digitorum superficialis. The tendon of the superficial flexor of the finger inserts at the base of the middle phalanx. To test its function in isolation (flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joint), hold all of the patient’s fingers in extension except for the one you want to test (Figs. 3.24). This draws all the deep flexor tendons distally and locks them. In an isolated complete tear of the flexor digitorum superficialis, flexion in the proximal interphalangeal joint will be significantly impaired. Since muscle tension proximally displaces the stump of the tendon in any injury to a flexor tendon, you should attempt to palpate the precise position of the proximal end preoperatively. The stump can also appear as a painful thickened area in the region of the proximal phalanx. The superficial flexor tendon can be absent; always compare both hands.

Fig. 3.25 Evaluation of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon.

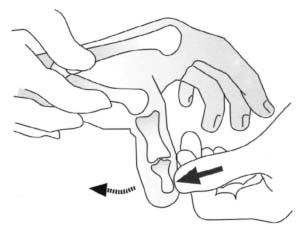

Flexor digitorum profundus. The tendon of the deep flexor of the finger inserts at the base of the distal phalanx. To evaluate its function (flexion in the distal interphalangeal joint), instruct the patient to actively flex the distal interphalangeal joint while you immoblize the proximal interphalangeal joint in passive extension (Figs. 3.25). An acute tear of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon renders active flexion in the distal interphalangeal joint immpossible; in an older tear, flexion will be significantly limited. Normal flexion in the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints will still be possible. If both flexor tendons are served, flexion will only be possible in the metacarpophalangeal joint using the interossei. When the patient places the hand with the dorsum flat on the examining table, the injured finger will be completely extended.

Flexor pollicis longus. Evaluate the function of the flexor pollicis longus tendon with the metacarpophalangeal joint immobilized in passive extension. If the distal interphalangeal joint cannot be flexed, then a tendon tear or paralysis of the muscle is present. Some flexion in the metacarpophalangeal joint may be possible if the thenar musculature is intact.

Evaluating Extensor Tendon Function

Clinical evaluation of extensor tendon lesions is more difficult than that of flexor tendon lesions because of the unique anatomy of the dorsum of the hand. Open injuries occur far more frequently than closed injuries, which are often accompanied by ligament tears with bony avulsion fractures. Function may still be present in partial tears of the extensors. Testing against resistance is required to distinguish partial tears from normal ligaments.

Fingers with three phalanges are extended using the extensor digitorum communis and the intrinsic muscles (interossei and lumbricals). The index and little finger also have their own extensor muscle. To test the function of the extensor digitorum tendon in isolation, have the patient extend the metacarpophalangeal joint against resistance with the interphalangeal joints flexed. When evaluating extension, remember that the extensor tendons influence each other through the juncture in the dorsum of the hand. An isolated lesion proximal to this connection will only result in a slight extension deficit as the affected finger can be extended via the extensor tendons of the adjacent fingers.

If active extension of the distal phalanx of a finger is not possible and the distal phalanx hangs flaccid (“drop finger”), this may be due to an intrasubstance tear in the extensor tendon, avulsion of the tendon from the distal phalanx, or a ligament tear with a bony avulsion fracture (mallet fracture).

Another frequent injury is a tear of the central slip of extensor tendon over the proximal interphalangeal joints. Swelling, hematoma, and tenderness to palpation over the dorsal aspect of this joint may be the only evidence of a tear of the central slip in an acute injury, unless a true lateral radiograph demonstrates an avulsion fracture over the extensor side at the base of the middle phalanx. Active flexion of the distal phalanx in the affected finger should be evaluated with the proximal interphalangeal joint immobilized in extension. Painful reduction of the active flexion in the distal interphalangeal joint can be an important sign of a tear of the central slip.

Stability Tests with Ligament Tears and Dislocations

• Interphalangeal joints

The interphalangeal joints are very stable although ligament injuries regularly occur, particularly in sports. These injuries most often involve the proximal interphalangeal joints. Injuries (tears) of the ligaments usually present as localized swelling and tenderness to palpation; signs of instability with passive hyperextension and lateral displacement are encountered less frequently. Test radial and ulnar opening at the proximal interphalangeal joints with the finger extended. If the palmar capsular plate is torn in addition to the collateral ligament, the middle phalanx will be displaced and tilted toward the uninjured side. Rotational instability will also be present.

Tears of the palmar plate. The palmar plate can tear as a result of dorsally directed force. Comparison of both hands is required to demonstrate abnormal hyperextension. The ligament tears many involve avulsion fractures of the bone.

Collateral ligament tears. Collateral ligament tears result from lateral forces, usually from the radial side. A clinically measured joint opening of less than 20° is regarded as a sign of an incomplete tear; a joint opening of more than 20° is regarded as a sign of a complete tear.

• Dislocations

Dislocations of the interphalangeal joints are immediately apparent from the resulting deformity in the dislocated joint. Evaluate stability after closed reduction.

Dorsal dislocation. Dorsal dislocation results from axial stresses with hyperextension. The distal palmar plate tears. This can be accompanied by a torn collateral ligament.

Palmar dislocation. Dorsal stresses and rotation of the flexed middle phalanx will result in palmar dislocation.

Lateral dislocation. The dislocation results from lateral forces. The respective collateral ligament and the volar plate tear.

• Metacarpophalangeal joints of the long fingers and thumb

The metacarpophalangel joints of the long fingers are ball-and-socket joints. They allow abduction and adduction in addition to flexion and extension. Collateral ligament tears are rare in these joints. In dislocations, the palmar plate tears as a result of strong hyperextension stresses. Dislocations can be complete or incomplete and dorsal or palmar. Complete dorsal dislocations occur more frequently. Here, the head of the phalanx will be palpable in the palm of the hand. Closed reduction is seldom possible because the palmar plate or tendons are interposed in the joint space.

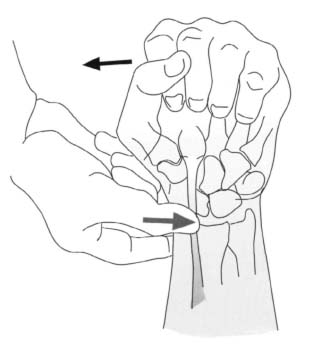

Stability test for an ulnar collateral ligament tear at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. Also known as gamekeeper’s thumb, this injury to the ulnar collateral ligament at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb occurs as a result of forced radial deviation of the extended thumb. This injury is often sustained in a fall on the hand. Evaluate stability with the thumb flexed 20°–30°; otherwise the accessory collateral ligament (if intact) can mask the tear of the collateral ligament in extension (Figs. 3.26). A joint that can also be opened in extension is the sign of a complex capsular ligament injury. Forceful stability testing can itself produce a surgical indication; abducting the thumb causes the collateral ligament to irretrievably slip beneath the extensor aponeurosis of the thumb, which precludes normal healing. Comparative examination of both hands is important as generalized ligament laxity can simulate a ski thumb.

Fig. 3.26 Stress test in a tear of the ulnar collateral ligament at the metacarpophalangeal joint.

• Carpometacarpal joints

Crush injuries and falls on the hand can produce dorsal dislocation of the fourth and fifth carpometacarpal joints as these are less stable. However, fracture dislocations in this region are encountered more frequently. These may present as a bayonet deformity of the hand, which can occasionally be masked by massive swelling. The carpometacarpal joint of the thumb is a very mobile joint. Complete dislocations are rare in comparison to Bennett fracture dislocations.

Tests for Nerve Compression

• Median nerve Carpal tunnel syndrome

Tinel’s sign. With compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel (carpal tunnel syndrome), you can elicit paresthesia by tapping the nerve at the site of compression (Figs. 3.27). This test will produce false negative results in cases where chronic compression has been present and nerve conduction significantly reduced for a long period of time.

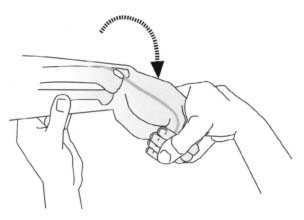

Phalen’s test. Maximum flexion or extension of the wrist can also lead to significant paresthesias in the distribution of the nerve in carpal tunnel syndrome (Figs. 3.28a, b). As with the Tinel’s sign, false negative results are possible in chronic cases.

• Radial nerve

Wartenberg syndrome

Tinel’s sign. When the margin of the brachioradialis compresses the superficial branch of the radial nerve in the distal forearm, tapping here can elicit tingling sensations.

Fig. 3.27 Tinel’s sign. Eliciting paresthesia by tapping the median nerve when carpal tunnel syndrome is present.

Figs. 3.28a, b Phalen’s test. Eliciting paresthesia by compression of the median nerve, at the end of the range of flexion and extension of the wrist, to evaluate carpal tunnel syndrome.

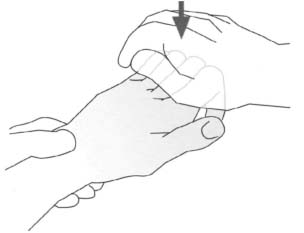

Fig. 3.29 Finkelstein test for evaluation of stenosing tenosynovitis (De Quervain disease).

• Ulnar nerve

Distal ulnar nerve compression syndrome

Tinel’s sign. This is sometimes negative. Distal ulnar nerve compressive neuropathy presents as a motor paresis of the ulnar nerve without loss of sensation.

Tests to Evaluate Vascular Supply

Allen test. This test is suitable for evaluating the radial and ulnar arteries in the hand. With the thumb, index finger, and middle finger, compress both arteries on the patient’s distal forearm. Then instruct the patient to open and close the fist so that the venous blood is pressed out of the hand through the dorsal veins. When the patient opens the fist, the palm of the hand will be pale. Removing compression from one artery while maintaining it on the other should normally cause the hand to rapidly flush pink as it is perfused. If the released artery is partially or completely occluded, this reaction will not be seen; the hand will only regain its normal color slowly. Test the second artery in the same manner, and repeat the test in the contralateral hand for comparison. If the hand does not become pale, even with increased pressure on both forearm arteries, a “median artery” or other arterial variant may be present. The Allen test can also be used to test vascular supply to a finger.

Other Tests

Finkelstein test. This test can be used to distinguish between simple radial styloiditis and stenosing tenosynovitis (De Quervain disease), a painful irritation of the synovial lining of the first dorsal compartment. Instruct the patient to adduct the thumb into the palm and make a fist. Immobilize the forearm and place the wrist in ulnar deviation. In a positive test, the patient will report pain in the tunnel (Figs. 3.29). This test will be false positive in patients with STT-arthrosis.

Examination of both motor and sensory function is required. Muscular strength is evaluated according to Table 1.8 (see p. 24).

Motor Function Testing

It is important to test motor function with direct muscle or tendon injuries and with central or peripheral nerve lesions. Electrodiagnostic studies are helpful and complement unusual clinical findings. To evaluate complete or partial motor paralysis, it is only necessary to test a few muscles. Complex nerve lesions, particularly peripheral lesions, require a standardized systematic evaluation of the musculature of the forearm and hand. Compensatory movements by muscles other than those being examined should be neutralized to avoid inaccurate diagnoses when testing the function of individual muscles. For example, failure of the dorsal interossei and the abductor digiti minimi can be masked by the function of the finger extensors if the test is done with the metacarpophalangeal joints in hyperextension. Similarly, the finger flexors can simulate movements of the palmar interossei if these muscles are tested with the long fingers flexed at the metacarpophalangeal joints. Other causes of inaccurate diagnoses include anomalies of innervation. These primarily affect the thenar region.

Wrist extension. The primary extensors of the wrist are the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis (radial nerve, C6–C7), and the extensor carpi ulnaris (radial nerve, C7). Secondary extensors include the extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, and extensor indicis proprius. Immobilize the patient’s forearm with one hand and instruct the patient to extend the wrist with the fist clenched against the resistance of your other hand.

Wrist flexion. The primary flexors of the wrist are the flexor carpi radialis (median nerve, C6–C8), and the flexor carpi ulnaris (ulnar nerve, C8–T1). Secondary flexors include the palmaris longus, the flexor pollicis longus, and the deep superficial finger flexors. The strongest flexor is the flexor carpi ulnaris. Flexion is best evaluated with a clenched fist against resistance because the clenched fist neutralizes the function of the finger flexors.

Ulnar deviation of the wrist. This is primarily due to the action of the flexor carpi ulnaris (ulnar nerve, C8–T1). Immobilize the patient’s forearm with one hand and instruct the patient to move the wrist into ulnar deviation against the resistance of the thumb of your same hand.

Radial deviation of the wrist. The main muscle effecting radial deviation in the wrist is the flexor carpi radialis (median nerve, C6–C8). The procedure is similar to that of the ulnar deviation test.

Fig. 3.30 Evaluation of finger extension.

Finger extension. The primary extensors include the extensor digitorum communis (radial nerve, C7–C8), extensor indicis proprius (radial nerve, C7–C8), and the extensor digiti minimi (radial nerve, C7). Test these muscles at the metacarpophalangeal joint with the wrist immobilized in a neutral position and the interphalangeal joints flexed. Flexion in the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints is necessary to prevent the intrinsic muscles and secondary extensors from contributing to the extension. (Figs. 3.30). Extension in the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints can be tested with a flicking movement of the fingers (Figs. 3.31). This test evaluates the function of the interossei and lumbricals (ulnar nerve, C8–T1).

Finger flexion. The primary flexors are the flexor digitorum profundus in the distal interphalangeal joint (ulnar part of the ulnar nerve, C8–T1, and radial part of the median nerve, C7–C8), the flexor digitorum superficialis in the proximal interphalangeal joint (median nerve, C7–C8), and the lumbricals in the metacarpophalangeal joint (median nerve, C7, for the medial lumbricals and ulnar nerve; C8 for the lateral lumbricals). For a preliminary test of the strength of the finger flexors, instruct the patient to flex the fingers. Interlock your fingers with the patient’s and try to pull them open. Differentiation between the superficialis and profundus is discussed in the previous section.

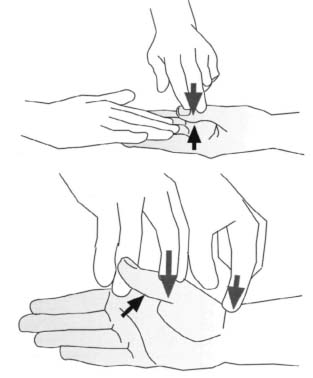

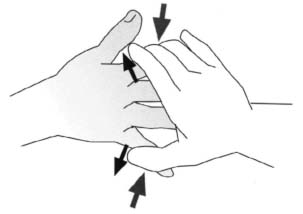

Finger abduction. The dorsal interossei (ulnar nerve, C8–T1), and the abductor digiti minimi (ulnar nerve, C8–T1) are the primary abductors. The long extensors of the fingers are secondary abductors. Abduction may be tested in all fingers simultaneously by applying resistance to the second and fifth finger (Figs. 3.32), or by testing the middle finger in isolation (Fig. 3.33).

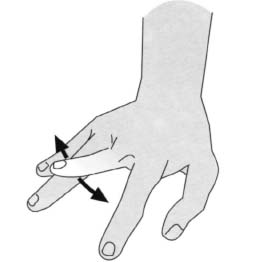

Finger adduction. The primary adductors are the palmar interossei (ulnar nerve, C8–T1). The long flexors of the fingers act as secondary adductors. To test finger adduction, try to pull the patient’s extended adducted phalanges apart. It is best to examine two fingers at the same time (i.e., index and middle finger, middle and ring finger, and ring and little finger). An alternative test is to try to pull a piece of paper from between the patient’s extended fingers while the patient attempts to maintain a grip on the paper. Compare the strength of this grip with the strength of the contralateral hand (Fig. 3.34).

Fig. 3.31 Evaluation of the interossei and lumbricals with a flicking movement.

Fig. 3.32 Evaluation of finger abduction.

Fig. 3.33 Evaluation of the abduction and adduction of the middle finger in isolation.

Fig. 3.34 Evaluation of finger adduction.

Thumb extension. The primary extensors are the extensor pollicis brevis at the metacarpophalangeal joint (radial nerve, C7), and the extensor pollicis longus at the interphalangeal joint (radial nerve, C7). When the thumb extensors are weak, extension can be effected at the metacarpophalangeal joint by the abductor pollicis.

Thumb flexion. The primary flexors are the flexor pollicis brevis at the metacarpophalangeal joint (deep part of the ulnar nerve, C8, and superficial part of the median nerve, C6–C7), and the flexor pollicis longus at the interphalangeal joint (median nerve, C8–T1). To test flexion, instruct the patient to flex the thumb toward the hypothenar eminence against the resistance of your thumb hooked into the patient’s.

Figs.3.35a, b Evaluation of the abduction of the thumb perpendicular to the palm; observation of the abductor pollicis brevis (a). Palpation of the tendon of the abductor pollicis longus adjacent to the tendon of the extensor pollicis brevis (b).

Figs. 3.36 Lüthy bottle sign.

Fig. 3.37 Froment sign

Fig. 3.38 Nail sign. Limited pronation of the thumb due to failure of the opponens pollicis. The thumbnail of the affected side is not completely visible.

Thumb abduction. The primary abductors include the abductor pollicis longus (radial nerve, C7) and the abductor pollicis brevis (median nerve, C6–C7). Evaluate these muscles with the thumbs abducted perpendicular to the palm (Figs.3.35a, b). With paralysis of the abductor pollicis brevis, the patient cannot bring the web between thumb and index finger into contact with a bottle when grasping it, as shown. This is known as the Luthy bottle sign (Fig. 3.36).

Thumb adduction. The adductor pollicis with its oblique and transverse heads is the primary adductor (ulnar nerve, C8). To evaluate adduction, first immobilize the ulnar side of the patient’s hand. Instruct the patient to attempt to place the extended thumb in a palmar-abducted position with the nail perpendicular to the palm of the hand. Now instruct the patient to adduct the thumb toward the index finger against resistance on the ulnar side of the thumb. Weakness of the adductor pollicis can be detected when the patient attempts to hold a piece of paper between the thumb and index finger. The flexor pollicis longus will compensate, producing forced flexion of the distal phalanx of the thumb known as Froment’s sign (Figs. 3.37).

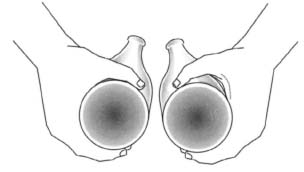

Opposition of the thumb and little finger. The primary muscles of opposition are the opponens pollicis (median nerve, C6–C7), and the opponens digiti minimi (ulnar nerve, C8). Evaluate opposition by instructing the patient to oppose the thumb and the tip of the little finger. Then grasp the thenar and hypothenar eminences with one hand each. Try to separate the fingers by pressing on the metacarpophalangeal joints. If the opponens pollicis is paralyzed, the thumb will be weakly pronated compared with the contralateral side (Figs. 3.38).

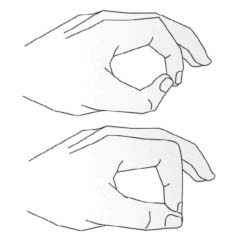

Fig. 3.39 “O” test. Patients with failure of the flexor pollicis longus and the second flexor digitorum profundus cannot form an “O” with the thumb and index finger.

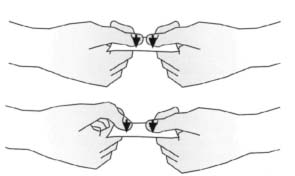

Pinch mechanism. The pinch mechanism is a combined motion involving several muscles. Normally, the thumb and index finger will form an “O”. With normal muscle function you will be unable to change the shape of the “O”, even with a strong pull, when you hook your index finger in the circle created by the two fingers. In an anterior interosseous nerve syndrome, the index flexor digitorum profundus and the flexor pollicis longus are paralyzed. The distal phalanx of the thumb and index finger will remain extended and the patient will be unable to form an “O” (Figs. 3.39).

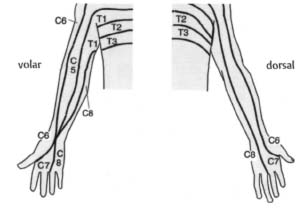

Examining Sensation

Examining sensation in the upper extremities is generally limited to evaluating pain and sense of touch. Usually tests for other qualities (temperature sensation and proprioception) are unnecessary. The history will often provide the first important signs of disturbed sensation. One should inquire in particular, about paresthesia and dysesthesia in the hand region. In addition to the location and the time of occurrence of pain, situations that can elicit pain symptoms are also of interest. Often one only needs to apply brief, focused tactile and algesic stimuli to confirm the tentative diagnosis. Insofar as they are not caused by cerebral or spinal lesions or disorders, sensory disorders follow the innervation pattern of the spinal nerve roots, plexus, and peripheral nerves. Knowledge of the segmental (radicular) and peripheral innervation pattern is crucial to making an accurate diagnosis. Overlapping between regions of sensory supply and variations in the pattern of sensory supply must also be taken into consideration. For example, the ring finger can be completely supplied by either the median nerve or the ulnar nerve. Figure 3.40 shows the segmental sensory supply to the hand.

Peripheral sensory innervation is supplied by the following nerves:

Fig. 3.40

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree