Giant Cell Arteritis & Polymyalgia Rheumatica: Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA)—also known as temporal arteritis—is the most common form of systemic vasculitis in adults. GCA is a panarteritis that occurs almost exclusively in older people and preferentially affects the extracranial branches of the carotid artery. The most feared complication of GCA is blindness, which usually can be prevented by early diagnosis and treatment with glucocorticoids. Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is an aching and stiffness of the shoulders, neck, and hip-girdle area that can occur with GCA, or more commonly, by itself.

Essentials of Diagnosis

General Considerations

Although the causes of PMR and GCA are unknown, the disorders share many risk factors and probably mechanisms of pathogenesis. Age is the greatest risk factor for developing either condition. Almost all patients who have GCA are older than 50 years (the average age of onset is 72). The incidence of GCA rises from 1.54 cases per 100,000 people in the sixth decade to 20.7 per 100,000 in the eighth decade.

PMR is 2–4 times more common than GCA, and its incidence also rises with age. Women are twice as likely as men to have GCA or PMR. Both conditions develop most often in Scandinavians and in Americans of Scandinavian origin. GCA rarely develops in black men.

GCA and PMR are associated with the same human leukocyte antigen genes as those seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (ie, human leukocyte antigen-DR4 variants *0401 and *0404). The pathogenesis of GCA appears to be initiated by T cells in the adventitia responding to an unknown antigen, which prompts other T cells and macrophages to infiltrate all layers of the affected artery and to elaborate cytokines that mediate both local damage to the vessel and systemic effects (Figure 30–1). The differential expression of inflammatory cytokines may explain the clinical subsets seen in GCA. Patients with the highest levels of interleukin-6, for example, are more likely to have fever and less likely to experience blindness. MRI and ultrasonography show that PMR is caused by inflammation of the synovial lining of the bursa and joints around the neck, shoulders, and hips.

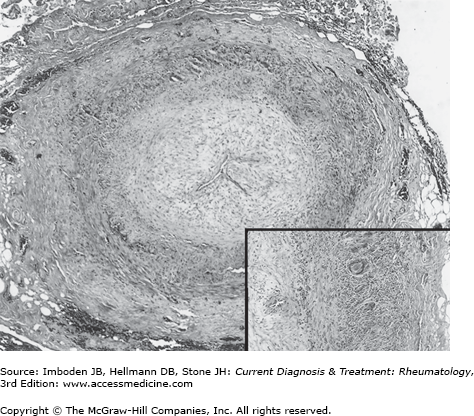

Figure 30–1.

Giant cell arteritis. Temporal artery biopsy showing endothelial proliferation, fragmentation of internal elastic lamina, and infiltration of the adventitia and media by inflammatory cells. Giant cells are especially well seen in the inset. (Reproduced, with permission, from Hellmann DB. Vasculitis. In: Stobo J, et al, eds. Principles and Practice of Medicine. Appleton & Lange; 1996.)

Although GCA may develop later in some patients with PMR, patients who have only PMR are not at risk for losing their vision and usually require small doses of prednisone (ie, <20 mg/day). In contrast, patients with GCA are at risk for losing their vision and require higher doses of prednisone (≥40 mg/day) to prevent blindness. Because patients who have GCA and PMR require treatment with glucocorticoids for months or years, it is important to minimize the likelihood of adverse effects from therapy (eg, osteoporosis, hypertension, and cataracts).

Clinical Findings

The classic symptoms of GCA include headache, jaw claudication, PMR, visual symptoms, and malaise (Table 30–1). The onset may be gradual or sudden. The American College of Rheumatology has developed classification criteria for the diagnosis of GCA (Table 30–2).

| Symptoms | Percentage of Cases |

|---|---|

| Headache | 70 |

| Jaw claudication | 50 |

| Constitutional symptoms | 50 |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 40 |

| Visual loss | 20 |

| Abnormal temporal artery | 50 |

| Anemia | 80 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate >50 mm/hour | 90 |

| Arthritis | 15 |

| Criteriona | Definition |

|---|---|

| Age at disease onset ≥50 years | Development of symptoms or findings beginning at age 50 or older |

| New headache | New onset or new type of localized pain in the head |

| Temporal artery abnormality | Temporal artery tenderness to palpation or decreased pulsation, unrelated to arteriosclerosis of cervical arteries |

| Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | ESR ≥50 mm/hour by the Westergren method |

| Abnormal artery biopsy | Biopsy specimen with artery showing vasculitis characterized by a predominance of mononuclear cell infiltration or granulomatous inflammation, usually with multinucleated giant cells |

The most frequent finding during a physical examination is an abnormal temporal artery, which develops in only 50% of patients; thus a normal temporal artery does not exclude the diagnosis of GCA. The temporal artery may be enlarged, difficult to compress, nodular, or pulseless. About 15–20% of patients have axillary or subclavian disease, which manifests as diminished pulses, unequal arm blood pressures, or bruits heard above or below the clavicle or along the upper arm. Tongue ulcers, mass lesions of the breast and ovaries, and aortic regurgitation are other signs of GCA.

The intensity and location of the headache, the most common symptom, varies greatly from patient to patient. The headache is typically described as a dull, aching pain of moderate severity, localized over the temporal area, but variations in location, quality, and severity occur often. The most striking feature of the headache is that the patient notices that it is new or different. Even if the patient has had migraine or other headache problems in the past, features of the new headache are different. Patients frequently describe tenderness of the scalp, especially when they comb or brush their hair. Some patients localize the tenderness to the temporal arteries, which may be enlarged or nodular in only a minority of cases.

Jaw claudication, defined as pain in the masseter muscles associated with protracted chewing, develops when the oxygen demand of the masseter muscles exceeds the supply provided by narrowed and inflamed arteries. Typically, patients with jaw claudication notice pain when eating foods that require vigorous chewing, such as meats, and little or no pain when chewing soft foods. Of all the possible symptoms of GCA, jaw claudication is the most specific for this disease. Many patients do not provide such a classic description of jaw claudication, and instead report a vague sense of discomfort along the jaw or face, with or without protracted chewing. Atypical manifestations of jaw claudication include discomfort over the ear or around the nose.

PMR is defined as pain and stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and hip-girdle area that are usually much worse in the morning. Criteria for the diagnosis of PMR have been developed (Table 30–3).

|

The shoulders are more commonly involved (70–95%) than the hips (50–70%). Shoulder pain in PMR may begin unilaterally but quickly becomes bilateral. Patients with PMR may report great difficulty getting out of bed, arising from the toilet, or brushing their teeth. People in whom GCA develops frequently describe feeling “old” for the first time at the onset of the disease. The stiffness is especially severe in the morning but may improve, usually a little but sometimes markedly, during the day. When asked to localize the pain, patients often say the pain is “in the flesh” rather than in the joints. Examination of the shoulders and hips is usually unremarkable except for decreased active and passive range of motion. Swelling, erythema, and heat are usually absent. However, some patients with PMR or GCA experience arthralgia or arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint, wrists, fingers, knees, or ankles. Rarely, pitting edema develops in the patient’s hands or feet.

About one third of patients with GCA have visual symptoms, chiefly diplopia or visual loss. Visual hallucinations occur rarely. The visual loss may be transient or permanent or monocular or binocular. Visual loss is the most feared complication of GCA because it is usually irreversible. Blindness can develop abruptly but more often is preceded by episodes of blurred vision or amaurosis fugax. Rarely is visual loss the first manifestation of GCA; on average, visual loss develops 5 months after the onset of other GCA symptoms. The direct cause of visual loss in GCA is usually occlusion of the posterior ciliary artery, a branch of the ophthalmic artery, which is a branch of the carotid artery. The posterior ciliary artery supplies blood to the optic nerve head. Interruption of that flow leads to anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree