Getting Started as a Regular Exerciser

Edward M. Phillips

Jennifer Capell

Steven Jonas

INTRODUCTION

By this stage of the book, you will have most likely come to the understanding that the hardest part of becoming and staying a regular exerciser is the mental work that has to be done at all the stages of the process: getting ready to begin, becoming active, and then staying with it. In the previous three chapters, we have dealt with the central mental task: mobilizing motivation and keeping it activated. In this chapter we will deal with additional mental aspects of getting started, whether your patient is going to try the lifestyle exercise approach or the leisure-time scheduled exercise approach, whether it be a sport such as running or an athletic activity such as aerobic dance.

Remember, if all that people needed were advice on what sports to do, and when to do them, we would have a nation of regular exercisers, and this book would be unnecessary. However, observation and research tell us that the majority of successful regular exercisers have spent a significant amount of time mentally preparing and engaging in their activity: thinking about what they are going to do and why they are going to do it. They use approaches on the order of either the Wellness Motivational Pathway (Chapter 5) or the Behavior Change Pyramid (Chapter 6). Further, we have suggested that you strongly advise your patient to take some time to think about what she is going to do and why she wants to do it, to write down her thoughts, and to then carefully consider what she has written even before taking that first step.

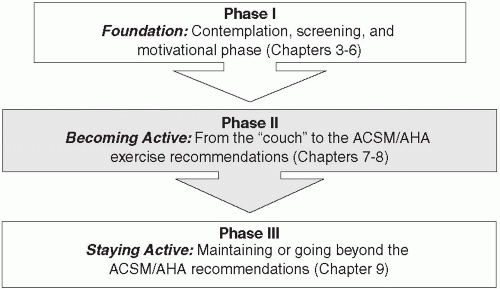

The process of assisting your patient in moving from a sedentary lifestyle to an active one can be broken down into three stages: the Foundation Phase, the Becoming Active Phase, and the Staying Active Phase. As you have discovered in the previous chapters of this book, a fair amount of the “work” involved with getting active happens before your patient begins his first “workout.” These pre-activity components, including progressing through the Stages of Change by the patient, screening and professional assessment to determine readiness for regular exercise and exercise risk for the patient, and Mobilizing Motivation make up Phase I, the Foundation Phase. These topics have been covered in Chapters 3, 4, 5, 6.

Once your patient has been adequately prepared to begin an exercise program, she enters Phase II, the Becoming Active Phase. In this phase, your patient will progress from a sedentary state up to the ACSM/AHA recommended minimal exercise levels (1). This phase is the focus of the present chapter and the next, and part of Chapter 10. Finally, once your patient has reached the nationally recommended minimum and has maintained it for some period of time (and has been sufficiently congratulated by you for doing so!), she will progress to Phase III, the Staying Active Phase, the topic of Chapter 9 and part of Chapter 10. In this phase, she will have a choice to maintain her current level at or above the ACSM/AHA minimum recommendations, or to safely progress to an even more active lifestyle. Figure 7.1 illustrates the three phases of lifestyle change from sedentary to active.

As we move into the actual prescription of exercise, we will present two options: the general principles of exercise prescription, which should enable you to prescribe a personalized program for your patients, and a specific program. The generalized principles are covered in Chapters 8 and 9, while the specific program is the topic of Chapter 10.

Although Figure 7.1 shows a linear progression through the three phases, patients can and will move between the phases over time. For example, motivation will periodically wane in all individuals, requiring the patient, with our without your assistance, to remobilize his motivation. Similarly, a patient who has reached Phase III could regress back to the ACSM/AHA minimum recommended levels, or even back to the sedentary level. In such situations, remind your patient that: a) every regular exerciser experiences such variations, at one level or another; b) he has not “failed,” or is a not a “bad” person for doing so;

and c) when he is ready to do so, you will be there to encourage him to return to whatever the appropriate phase, and start progressing again.

and c) when he is ready to do so, you will be there to encourage him to return to whatever the appropriate phase, and start progressing again.

THE KEY PRINCIPLES FOR SUCCESSFULLY PRESCRIBING REGULAR EXERCISE

Key Principles for Successful Exercise Prescription

Set “SMART” goals

Focus first on the “regular” in “regular exercise”

Gradual change lead to permanent changes

More is better than less, but something is better than nothing

Set “SMART” Goals

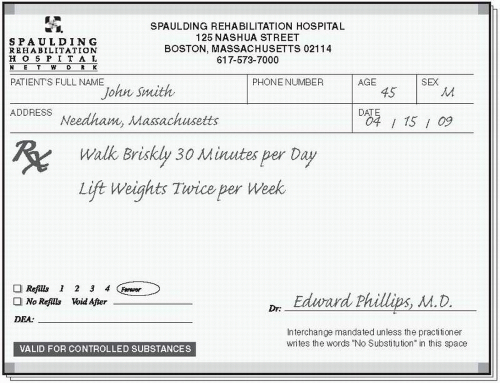

As we have discussed earlier, it is critical that your patient has a well-defined goal(s) that she is working toward. As with any goal, your patient’s active lifestyle goals should follow the “SMART” (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time-Bound) formula. These points will be elaborated upon as we proceed. We encourage you to write your patient’s goal(s) on her Exercise Prescription to ensure that, together, you have determined the goal(s). This then becomes a handy reminder for your patient as she progresses toward the goal(s). Some patients do set multiple goals for themselves, which can be helpful in both mobilizing and maintaining motivation. As we have noted more than once, when setting a goal, your patient should consider questions such as what the primary reason(s) is for becoming more active: Why is this important? What do I expect to get out of the activity? Am I prepared to make the adjustments in lifestyle in order to reach the goal? (See Figure 7.2.)

Focus First on the “Regular” in “Regular Exercise”

Patients will have the greatest chance of success if they focus first on the “regular” component, rather than on the “exercise” component of “regular exercise.” Assuming that the mental preparation and planning have been done appropriately, we recommend that your patient begin by focusing first on developing the habit of regular exercise by building the time for exercise, whether in the lifestyle or the leisure-time scheduled approach, into their life on a regular basis. Before your patient can succeed at committing to any given activity, he needs to convince himself that he can do it on a regular basis. The ACSM and AHA recommend that adults be moderately physically active for 30 minutes at least five days a week, or for 20 minutes at least three days each week if participating in vigorous exercise. Moderate-intensity exercise is

defined as working hard enough to noticeably increase heart rate and breathing, yet still being able to carry on a conversation, and vigorous exercise is activity that substantially increases heart rate and breathing. Vigorous-intensity exercise is formally defined as >60% [V with dot above]O2 R. See Chapter 8 for a more extensive discussion of exercise intensity (2). In addition, it is important to discuss the regularity, or distribution, of activity throughout the week. It is preferable for your patients to try to distribute their activity sessions throughout the week, rather than fitting all activity into the weekend, for example. An even distribution, especially as the activity level increases, is less likely to cause overuse injury, can help increase metabolism for a greater period of time over the course of the week, and provides a greater benefit for both the heart and skeletal muscles. In the non-conditioned person, intermittent episodes of a significantly increased heart rate can increase the risk of sudden death from heart attack. These heart rate increases may result from activities such as climbing several flights of stairs quickly while carrying a heavy briefcase. With respect to the musculoskeletal system, muscles worked out on a regular basis, on alternate days at least, go through a cycle of build-up, breakdown, and further build-up. This process leads to increased endurance and strength.

defined as working hard enough to noticeably increase heart rate and breathing, yet still being able to carry on a conversation, and vigorous exercise is activity that substantially increases heart rate and breathing. Vigorous-intensity exercise is formally defined as >60% [V with dot above]O2 R. See Chapter 8 for a more extensive discussion of exercise intensity (2). In addition, it is important to discuss the regularity, or distribution, of activity throughout the week. It is preferable for your patients to try to distribute their activity sessions throughout the week, rather than fitting all activity into the weekend, for example. An even distribution, especially as the activity level increases, is less likely to cause overuse injury, can help increase metabolism for a greater period of time over the course of the week, and provides a greater benefit for both the heart and skeletal muscles. In the non-conditioned person, intermittent episodes of a significantly increased heart rate can increase the risk of sudden death from heart attack. These heart rate increases may result from activities such as climbing several flights of stairs quickly while carrying a heavy briefcase. With respect to the musculoskeletal system, muscles worked out on a regular basis, on alternate days at least, go through a cycle of build-up, breakdown, and further build-up. This process leads to increased endurance and strength.

Gradual Change Leads to Permanent Changes

Being sedentary or being active is a habit. Habits are hard to break. Changing a sedentary habit into an active habit will take time and is best tackled in small increments. In Chapter 8 you will learn how to actually prescribe exercise for your patients as you might prescribe any other health-related intervention, and to help them maintain or progress their exercise program over time.

In this process, you will help your patient to determine a starting point that does not seem overwhelming or difficult to her, and from there, to progress by small amounts each week. This approach decreases the chance of overuse injury and increases the chances of success in changing her sedentary habit into an active habit. For most people, “too much, too soon,” whether in the lifestyle or leisure-time scheduled approach, will lead to muscle pain and possible injury, as well as to greater likelihood of early quitting. Furthermore, a series of small, “doable,” changes will soon result in big changes. A few weeks or months into the program, your patient will likely look back at the extent of her progress, and be surprised but motivated and proud of her accomplishments.

The encouraging news is that just as a sedentary habit is hard to break but can be done if done gradually, an active habit is also hard to break—meaning that once your patient has made the effort to gradually change his habit and to incorporate regular activity into his lifestyle, it will be significantly easier to maintain this new way of life. In fact, he will most likely even enjoy the benefits of the exercise!

More Is Better than Less, but Something Is Better than Nothing

Throughout this book, we recommend that your patients strive to reach and maintain an exercise level of at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity, or 60 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise each week—the recommendations established by the ACSM and AHA. The benefits of physical activity increase with the amount of activity performed, because of the dose-response relationship between exercise and the health benefits accrued from the exercise. Therefore, as your patients begin and progress through their exercise program, they should be encouraged to keep increasing at a safe rate of progression at least until they reach the national minimal recommended levels.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree