Working with elderly patients in a nursing home or similar institutional environment is a challenging task for a practitioner of any discipline. Although individually the number of illnesses these patients may suffer from is quite large, as a group they share certain conditions in common, which distinguish them from other patients receiving Oriental medical treatment. The practitioner needs to become aware of these features in order to deliver the best healthcare possible to this sometimes neglected segment of our population.

While treatment modalities are almost intrinsically connected to diagnosis, there are still general treatment principles that are part of the infrastructure of Oriental medicine that are worthy options for this group of patients. If the practitioner has an opportunity to treat such patients he/she should realize that geriatric patients are different from the average person encountered in an outpatient setting. Because of their age, delicate condition, and clinical complexity, there are treatment adaptations that are critical in the care of the elderly person.

Additionally, a more generalized diagnostic approach to thinking about the older patient is presented, such as the complexity of their medical history, possible drug and herbal interactions, how to diagnose their pain, and classical and modern Oriental approaches to aging, which can illuminate treatment plans, acupuncture points, and herbal selection. Each of these parameters is discussed below.

The problems of the elderly are frequently compound and complex. Their problems can range from physical to mental, and some may have both. This is no surprise to the practitioner who sees the relationship between the physical and mental manifestations of the self. There is a preponderance of mental disorders such as senile dementia or Alzheimer’s disease and from a Chinese perspective, there can be complicated syndromes characterized by the secondary pathological products of stagnant blood and phlegm, which are pernicious and difficult to treat. Patients in nursing homes, assisted living centers or other similar environments are also confined due to a variety of reasons. Whether ambulatory, bedridden or wheelchair-bound, in general they require a degree of care they or their family cannot provide.

In directing treatment toward the elderly, combine compassion with realism. Consider their conditions to see what you can do. To a certain degree some of their symptoms can be addressed. Aid and comfort in the form of human interaction, appropriate professional touch, and the instruments of Oriental medicine, can go a long way, so while cure may not be attainable, the reconciliation of the condition, that is, healing, can occur. The specific guidelines for treatment that I have used to direct my treatment approach for the elderly are discussed below.

General Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients in Institutional Settings

General Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients in Institutional Settings

- Make sure you have the written consent of your patient or appropriate guardian when treating the elderly patient.

- With all patients, medical history is important, but thorough personal medical history is of utmost importance in treating the elderly due to their often weakened condition and the multiple illnesses they may have. Obtain a complete medical history so you know all the conditions the patient has. It is more likely that they have a more lengthy medical history than a younger person simply due to age. You will probably need to get this information from the patient’s medical chart as they may not remember their complete history or have the ability to talk at length with you. Due to the patient’s age, length of the history, memory problems, and complexity of the case, communication with their physician is important. Hence. the Oriental medical provider should cultivate skills in communicating with the Western doctor. Diagnosed illnesses will usually imply that the patients are also taking multiple Western medications, which singularly or in combination may produce certain side-effects, which can be further complicated with Oriental herbs. See a discussion of herbs and the elderly later in this chapter.

- Discuss anything in the medical chart you don’t understand with the patient’s assigned medical personnel such as their doctor or nurse.

- Treat those who are able to articulate how they feel or those you feel can sustain and benefit from Oriental medical therapy.

- When you have identified the complaint against the background of their medical history, explain to the patient and/or their family in clear, simple terms what you will be doing, what you hope to attain, what techniques you will be using, and what the treatments may feel like. Don’t make promises about the outcome, but do inform each group about all of these things so they have a sense about what is occurring in treatment and its possible outcome.

- Proceed slowly. Do not attempt to do too much in any one treatment, especially for the elderly whose vital qi is weak. Evaluate therapeutic outcome weekly.

- Patients are individuals. Choose the modality of treatment that best corresponds to the patient’s condition. The major modalities employed in Oriental medicine for the elderly and their suitability are discussed later and summarized at the end of this chapter in Table 7.5.

- Realize that for the most part, these patients are now in their final home. They are here to be cared for. This is probably the place where they will die and many of them know this. They may be despondent and depressed. While the things you can do for them may be limited, your presence alone can give them solace and that attention is good medicine.

- Discuss anything in the medical chart you don’t understand with the patient’s assigned medical personnel such as their doctor or nurse.

Treatment Adaptations

Treatment Adaptations

Patient Positioning

As with the administration of most acupuncture, a supine position is generally recommended for treatment. Especially with the elderly though, there are times when this is not possible due to their limitations. However, if a treatment must be administered in a sitting position such as in bed or a wheelchair use caution in needling chest points such as LU-1 (zhong fu) or CV-17 (shan zhong). In general, avoid abdominal needling such as CV-12 (zhong wan) in such patients. In these cases, if the patient moves in treatment or has a sagging posture, the needle could become displaced and possibly cause a pneumothorax, break, bend, or become deeply embedded in the tissues.

Be careful treating patients reclining on their stomachs when receiving acupuncture. Support their necks with a face cradle that is properly angled. This position may be contraindicated for patients with respiratory illnesses, back pain, severe abdominal distention or illnesses of the abdominal cavity, or for patients on oxygen.

Geriatric Pathology: Kidney Vacuity, Stagnant Blood, and Phlegm

Geriatric Pathology: Kidney Vacuity, Stagnant Blood, and Phlegm

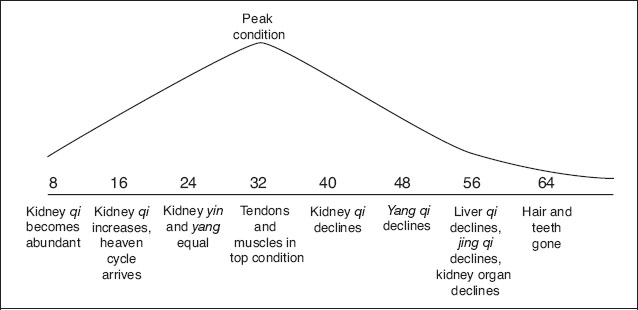

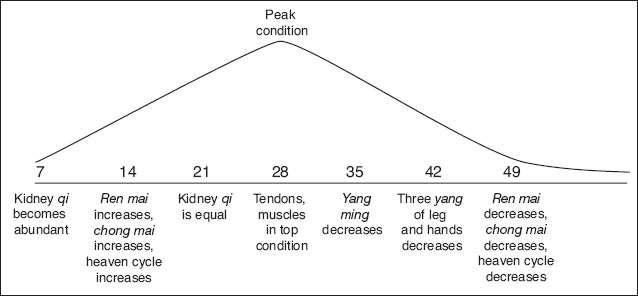

Historically in Chinese medicine, most illnesses of the elderly have been attributed to the decline of kidney qi as outlined in the qi cycles for men and women (Figs 7.1) and (7.2), or a combination of spleen and kidney vacuity. While kidney qi, which is responsible for growth, maturation, and development, inevitably declines over time, the illnesses of the elderly should be relatively benign if we use this model exclusively to predict aging pathology. Under this scenario hearing diminishes, teeth and bones become brittle, hair grays or is lost, the menses cease, eyesight lessens, and digestive disorders ensue. Certainly these conditions do indeed occur, yet as physicians we know that the illnesses most of the elderly are developing today are much more complex, devastating, and life-threatening than those one would predict according to the kidney qi.

Age 8 The kidney qi becomes abundant, the hair begins to grow longer, and the teeth begin to change.

Age 16 The kidney qi becomes more abundant, he begins to have his heaven cycle, he is full of jing-qi (semen), he can ejaculate and have a child; intercourse (yin/yang harmonization possible).

Age 24 The kidney qi is equal (i.e., kidney yin/yang are balanced), the tendons, muscles, bones, become strong; the wisdom teeth grow.

Age 32 All tendons, muscles, bones in top condition.

Age 40 The kidney qi weakens, the hair begins to fall off, and the teeth begin to wither.

Age 48 The yang qi in the upper part of the body declines, with the complexion looking withered, hair turns grey.

Age 56 The liver qi begins to weaken, the heaven cycle becomes exhausted, the jing-qi (semen) becomes scanty, and the kidney organs decline, and all parts of the body begin to grow old.

Age 64 All hair and teeth are gone.

Stagnant Blood

Yan De-Xin, a contemporary Chinese physician, has revolutionized Chinese views on gerontology with his thesis that most modern day illnesses are caused by blood stagnation. It is his theory that static blood (yu xue), a causative factor of illness in and of itself, likewise is the etiological precursor, which can cause multiple qi and blood disorders.

In Chinese medical theory, blood stagnation is problematic because it involves blood and qi stasis, and movement of both are requisite for the healthy human organism. This physiological occurrence seems to be an integral part of the pathologies of aging, and the reader, if interested, should acquaint him/herself with Yan De-Xin’s thesis, which expounds the etiology and subtle clinical manifestations of blood stagnation.1 Table 7.1 shows the patterns of static blood as gleaned from subjective symptoms, medical history, physical exam, organ systems, and laboratory findings, according to Yan De-Xin2, and a diagnosis of static blood pattern may made by looking at the evidence of all these things. Clinically, if there are more than four criteria within any two of these categories, one may diagnose the disease as manifesting a pattern of static blood.

Yan De-Xin amply supports his theory with classical sources. One idea he advances is that drugs are a leading cause of blood stagnation. Because the elderly may be on or may have taken many drugs, their health is intimately connected to their drug history. His preventative regimes revolve around strengthening the qi, activating the blood, and transforming stasis. For the clinician, this suggests the use of blood-activating herbs and acupuncture points, which perform similar functions. Consult “Recognition and prevention of herb—drug interactions” by Chen3 to ascertain that the blood stasis herbs chosen are not contraindicated for the patient, for instance that the patient is not on Coumadin (warfarin—a blood thinner) or has any coagulation problems.

Fig 7. 2 The qi cycle for women.

Age 7 The kidney qi becomes abundant, the hair begins to grow longer, and the teeth begin to change.

Age 14 The ren mai begins to flow, the heaven cycle begins, and the chong mai begins to grow in abundance, menstruation begins, pregnancy is possible.

Age 21 The kidney qi becomes equal (i.e., the yin/yang are balanced), the wisdom teeth begin to grow.

Age 28 The tendons, muscles, bones become hard, the hair grows to the longest, the body and mind are in top condition.

Age 35 The yang ming channels begin to weaken with the result that the complexion starts to wither, the hair begins to fall off.

Age 42 The three yang channels of the hands and legs begin to weaken, the complexion looks even more withered, the hair turns grey.

Age 49 The ren mai becomes deficient, the heaven cycle becomes exhausted, the chong mai becomes weakened and scanty, her body becomes old, she can not become pregnant

Acupuncture does not have the biological complexity of herbs because the needles regulate the physiological functioning of qi and blood. Table 7.2 provides a prioritized list of the points I have found to be the most useful in activating the blood. I highly recommend the integration of at least one of these into any acupuncture prescription. If not actually needled they can be palpated by the practitioner prior to treatment as part of a diagnostic assessment of blood stagnation. Additionally, the patient can be taught to stimulate these points on a daily basis by rubbing them vigorously for two to three seconds or the practitioner may do so during treatment. If needling is performed, needles may be inserted to the standard depths of insertion in the standard locations using a dispersion technique. Needling retention time depends upon the balance of the treatment the practitioner is administering but is usually 10 – 15 minutes.

Phlegm

Contemporary and ancient scholars provide added insight into geriatric pathology in their discussions of the secondary pathological product of phlegm. Of course, in Oriental medicine the concept of phlegm is very complex and extends beyond the narrow definition of respiratory secretions, but those well trained in Oriental medicine should understand its nuances. Some interesting concepts about phlegm from Cheung4 are listed below and can be applied to the elderly. Following each of these scholarly observations, I have listed my comments in parentheses:

- To manage intractable diseases and bizarre disorders never overlook the possibility of phlegm. (Certainly many geriatric diseases such as Alzheimer’s are intractable and bizarre and seem to have a phlegm component.)

- When definitive management fails the hidden culprit may be phlegm. (It is difficult to manage many geriatric diseases, hence phlegm is likely involved.)

- Dysfunction of every organ can generate phlegm. (As we know, with age, organ function declines; hence the possibility of phlegm formation escalates.)

- Eight out of ten people are plagued by phlegm. (Apart from obvious clinical manifestations, statistically the elderly are automatically part of this group.)

- Prolonged retention of turbid phlegm will easily cause an accumulation of static retention of ecchymotic blood, which will promote congealing of phlegm. (This illustrates the cyclic inter-relationship between phlegm and blood stasis. Phlegm can lead to blood stasis, which in turn can exacerbate the original problem of phlegm. Additionally, blood and phlegm have the same origin, which is fluid. Hence, there is often a common denominator between the origins of static blood and phlegm formation.)

- In terms of treatment many ancient scholars admonish, “Those who are skillful in managing phlegm, do not directly treat phlegm, but treat qi.” (Treating the qi certainly assists the practitioner in addressing the root of the problem to bring about greater resolution of the phlegm. As we have already established, qi vacuity is also a major component in illnesses due the natural decline of vital qi. As far as an overall treatment strategy is concerned this approach makes sense, because it is the vacuity of the organs’ functions that is the root of the phlegm formation.)

| Signs and Symptoms of Static Blood | |

| Subjective symptoms | |

| Fever | Generalized fever, for instance, tidal fever. Local fever in specific areas, i.e., skin, muscle, etc. |

| Pain | Immovable, fixed |

| Bleeding | Excessive and difficult to stop as in hemoptysis, hemafecia |

| Distention | Certain areas of the body such as head and eyes experience distention that does not decrease. Continues over time |

| Itching | Feeling of crawling beneath skin |

| Numbness | Inability to feel or electrical feeling, lack of perception of heat and cold |

| Stiffness | Stiff, inhibited movement such as with the neck |

| Dry mouth | Mouth dry, but not thirsty |

| Dreams | Little sleep but dreams of danger and fright |

| Memory | Insomnia, palpitations, poor memory |

| Mental states | Senility, dementia, crazy speech |

| Symptoms in the organ systems | |

| Heart | Palpitations, heart pain, disturbed shen, mania, angina |

| Liver/Gall bladder | Depression, agitation, easy vesation, floaters |

| Spleen/Stomach | Epigastric and abdominal pain and aching, lack of eating, constipation, diarrhea |

| Lung | Enduring cough, panting, phlegm tinged with blood |

| Kidney | Lower abdominal distention, urination problems, constipation |

| Physical signs | |

| Hair | Withered, dry, yellowish, weak hair |

| Face | Dark complexion |

| Eyes | Dark around the orbit, yellow sclera |

| Ears | Deafness |

| Cheeks | Red flush or lines |

| Nose | Red marks |

| Lips | Dark lips |

| Chin | Dark chin |

| Tongue | Dark red or purple with stasis marks |

| Neck | Distended veins, lumps |

| Chest | Stirring or throbbing of chest |

| Abdomen | Abdominal distention, masses, hardness |

| Back | Painful protruding vertebrae |

| Limbs | Enlarged toes and fingers, coldness |

| Skin | Stiff dry scaly skin, lumps, moles, patches |

| Voice | Hoarseness |

| History | |

| Chronic illness | Enduring disease must have stasis |

| Surgery | Internal adhesions and scars |

| Menses | Menstrual problems |

| Reproduction | Infertility, menopause |

| Lifestyle | Smoking, alcohol, sweet, fatty foods |

| Injury | External |

| Laboratory examination | |

| Blood | Viscosity of blood and plasma increased, hyperlipidemia, high bilirubin, increased erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets |

| Nail bed circulation | Increased capillary loops, decreased velocity, exudation, and bleeding |

| Cardiac system | Damaged myocardium, enlarged heart, diseased valves, reduced blood flow |

| Internal organs | Enlarged spleen and liver, lung or abdominal tumors, polyps, diverticula |

| Brain | Cerebral arteriosclerosis, epilepsy, cerebral hematoma or tumor |

Table 7.1 Patterns of static blood

| Points | Energetics |

| KI – 1 (yong quan) | The primary point for vascular problems. Diagnostic and treatment point for blood disturbances anywhere in the body. Improves circulation and regulates blood pressure because the source of blood is in the kidneys |

| LI-4 (he gu) | As the metal point on a wood channel (metal controls wood), regulates the smooth flow of qi in the lower burner. Because the blood follows the qi, it regulates blood flow as well. Major point to move blood stagnation inlower jiao (one of the three burners) |

| SP-10 (xue hai) | Sea of Blood point. Intersects with the chong mai vessel. Treats blood stagnation anywhere in the body, particularly in the lower abdomen |

| BL-17 (ge shu) | Influential point that dominates the blood. Back shu point of the diaphragm. Moves the blood by moving the qi of the diaphragm |

| ST-25 L (tian shu) | Diagnostic point for blood stagnation anywhere in the body due to its connection to the liver. At this point, the portal vein goes to the liver |

| SP-6 (san yin jiao) | For blood stagnation in the abdomen due to poor venous circulation or problems of the liver, spleen, and kidney channels in bringing qi and blood to the middle jiao |

Table 7.2 Clinically effective points to resolve blood stasis

Phlegm is a difficult pathology to remediate because its nature is heavy, turbid, and sticky, and its formation is usually a result of zang fu organ dysfunction, static blood, or pre-existing phlegm. In the elderly, diseases characterized by phlegm are numerous. They include gallstones and kidney stones, atherosclerotic plaques, arthritic bone deformities, mania, psychosis, memory problems, edema, facial paralysis, cough, chronic bronchitis, joint pain, stroke, digestive disorders, angina, vertigo, coma, burning leg sensations, and atrophic limbs. For perhaps the most comprehensive discussion of phlegm see CS Cheung’s Abstract and Clinical Review article on phlegm4, which details it in its myriad formations with corresponding differentiations and herbal formulae. Table 7.3 reminds the practitioner of points that are clinically effective in the resolution of phlegm. It comprises the points I have found most useful in its management.

| Points | Energetics |

| LI-14 (bi nao) | Resolves phlegm and disperses masses anywhere in the body, particularly in the upper jiao and head |

| ST-40 (feng long) | As the luo point of the stomach, sweeps phlegm from the body |

| SP-4 (gong sun) | Drains excesses such as damp and phlegm from the spleen and stomach |

| CV-12 (zhong wan) | Resolves phlegm in the spleen and stomach |

Table 7.3 Clinically effective points to resolve phlegm

Physical Limitations

Physical Limitations

As they age, some patients will never regain full control over their bodies. Like them, we need to recognize these physical limitations. For instance, do not try to make a patient walk without a walker if the patient’s physician has required it or if the patient is incapable of walking. Likewise, check bone density levels in suspect patients to see if they have the weight-bearing capacity to allow them to walk. Ultimately, what we are trying to do in our treatment is to enhance the quality of life of the patient. Oriental medicine can assist in this goal because it is predicated on natural forces that promote proper physiological functioning.

Pain

Pain

Many of the disorders suffered by the elderly have pain as a component, and this pain is usually chronic. As such, it tends to affect the quality of life adversely. Whether it is the pain of an illness like arthritis, or low back pain, chronic neuropathy, advanced painful malignancies, post-fracture or post-operative pain, pain relief should be part of a larger pain management plan that usually requires several modalities. Appropriate treatment plans require a precise differentiation of the pain. A comprehensive discussion of pain differentiation and a multi-disciplinary pain management plan is listed in my article “The differential diagnosis of pain in classical Chinese medicine.”5

While an Oriental medical practitioner’s frame of reference for treating pain is very broad due to its definition of pain, the Western model has more limitations. Even the National Institute of Health’s Consensus Statement maintains that acupuncture, tai qi, qi gong, and tuina techniques adapted for the elderly are useful therapies; there are few side-effects—a consideration of note, especially for a population that has many health disorders. 6

Treatment Modalities

Treatment Modalities

The TDP Lamp or the Mineral Infrared Therapy Device

The TDP lamp or the far infrared device are two superb tools for conferring therapeutic heat that can correct many conditions. Due to the size of the lamp they are not the most practical tools to bring to a nursing home on every trip, but if they can be stored there they are excellent choices for elderly patients. The heat of the lamp is relaxing, soothing, and comforting. The modality itself is non-invasive and able to treat large local areas such as the back or abdomen. The use of the lamp is suitable for a variety of conditions, especially yang vacuity that the elderly tend towards, by promoting increased metabolism and increased blood circulation.

Excellent results can be obtained both for musculoskeletal problems such as shoulder, back, or neck tension, or for internal problems such as frequent night-time urination, diabetes, insomnia, skin disorders, and neurasthenia. The lamp is effective for other problems such as arthritis, soft tissue injuries, sciatica, bedsores, or the rehabilitation and restoration of any diminished normal function following illness, injury, surgical intervention, or age-related degeneration. As with any treatment, frequency of treatment and length of application of the therapy vary according to the patient’s presentation.

Each of the devices works slightly differently and more can be read about each particular device by consulting the product literature but what they have in common are all of the aforementioned features. See Chapter 20 for a further discussion of the TDP lamp and Figure 20.1 for a photograph.

Palpation

Palpation is the process of examining the surface of the body by touch to detect the presence of disease. Sometimes it involves the use of pressure to certain points or areas to determine the patient’s reaction to that touch. This technique is usually not that effective if the patient’s vitality is low as is the case for many of the elderly. They tend not to be able to respond to the diagnostic palpation. Patients may also perceive the procedure as painful instead of as a message about their bodily condition. However, areas of heat, cold, tension, or flaccidity can be determined through palpation and interpreted by the practitioner. Be gentle.

Scalp Acupuncture

Scalp acupuncture is a microsystem of Oriental medicine, which utilizes needling points on the scalp to treat a variety of disorders. It is highly effective for a subset of conditions such as musculoskeletal problems that include muscular atrophy, motor impairment, sequelae of post-stroke disorders, paralysis, involuntary movement problems, multiple sclerosis, and other difficult-to-treat conditions where there is nervous system involvement. The elderly in nursing homes may have many of these ailments.

Electricity

Electrical acupuncture is a method by which electricity is applied to acupuncture needles in order to provoke a constant stimulus to the needles, which is difficult and even impossible to achieve by hand, or to impart an electrical charge to an acupuncture point. It can be employed for numerous conditions, most notably bi-syndromes, which are conditions characterized by obstruction with symptoms of pain, or inflammation. Electricity is useful in inducing analgesia because of its superior ability to stimulate the needles with a frequency that cannot be elicited by hand. It is the frequency of stimulation that disperses the obstruction causing the pain or inflammation.

Personally, I do not employ electricity to any patient due to its cold nature. Additionally, because many symptoms of the elderly can be categorized as yang vacuity, it may be incompatible with their conditions. The stimulus can also be very jarring and unpleasant, particularly to a delicate older person. The use of electricity is contraindicated for patients with heart conditions and pacemakers.

Needles

Needles of course are the primary instrument of Oriental medicine. They are used to regulate the flow of qi and blood in the channels. Needles may be employed to treat the elderly, however, keep the following points in mind when treating these patients:

- Their vital qi may be weak, hence it becomes difficult to get the de qi stimulus.

- Due to decreased vital qi, use few needles so as not to deplete the patient’s energy. In general, apply a mild stimulus if any and insert shallowly.

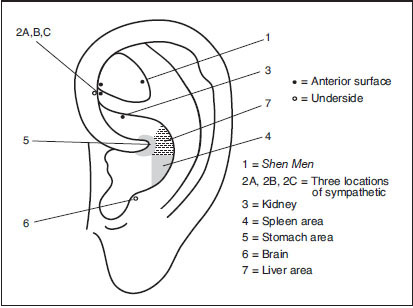

- All body parts may not be readily accessible to needling if the patient is in a wheelchair or bedridden so select points in consideration of the patient’s ability to move. Through the microsystem of the ear or the scalp however, all body parts and organs can be treated with needles. Both are excellent choices.

- Fine needles inserted with a tube should be used to prevent bruising, bleeding, or trauma to these delicate patients. I recommend using a #1 gauge, 30mm Seirin needle.

| Point | Energetics |

| 1. Shen men | Quiets the heart, calms the spirit, and puts the patient into a state of receptivity for the treatment. For restlessness and common mental disorders. Neutralizes toxins, cures inflammation. Additionally is one of the best clinically effective points for pain because it pertains to the heart. The Huang Di Nei Jing text says, “When the Heart is serene, all pain is negligible.” Good for insomnia. The elderly may have all of these as problems |

| 2. Sympathetic (three locations) | Relieves pain. The elderly have many disorders characterized by pain. Regulates the autonomic nervous system. Dilates blood vessels; for opthamalogical diseases |

| 3. Kidney | To tonify the root qi of the body, the foundation yin and yang, which declines with aging |

| 4–5. Spleen and stomach | To reinforce post-natal qi, which is frequently weak in the elderly due to age and poor nutrition. Builds blood. Since the spleen dominates the muscles, this combination is good for weak muscles that the elderly may have due to lack of exercise or other factors |

| 6. Brain | Regulates neurological function, benefits the mind. Regulates excitation or inhibition of the cerebral cortex. General treatment point for diseases of the nervous, digestive, endocrine, and urogenital systems. For neuropsychiatric disorders. Also for insomnia and prolapse, common in the elderly |

| 7. Liver | Promotes free-flowingness of qi in the body. Maintains the harmonious relationship between the internal and external environment. Moves blood, moves stagnation, builds blood and yin, increases energy |

Note: Modify according to other signs and symptoms; i.e., add points for specific conditions or areas of pain such as prostate, low back, or hypertension.

Table 7.4 Standardized ear treatment for geriatric patients

Auricular acupuncture

Auricular acupuncture is a method of diagnosing and treating through the microsystem of the ear. It is one of the most useful methods of treatment for any patient regardless of age or condition. It has a high rate of efficacy in adjusting the flow of qi and blood in a relatively non-invasive manner, and is suitable for musculoskeletal, internal, emotional, chronic, and acute problems including pain and inflammation. The ear is easily accessible to treat.

Auricular acupuncture is an extremely effective modality to employ for the elderly; in fact, it is my method of choice. Table 7.4 presents a core ear acupuncture treatment I have constructed, which I use as a skeletal outline in the treatment of elderly patients. Based upon specific signs and symptoms, this formula may be modified. An illustration of these points is also provided in Figure 7.3.

Almost unequivocally I employ gold Magrain pellets in one ear then alternate ears for subsequent treatments. Clean the ear well. Use gold pellets to ward off infection in patients who may have reduced wound-healing capacity. Retain the pellets for 3 to 5 days unless the patient is exposed to water or high humidity levels, which could increase the risk of infection—in which case the pellets are worn for fewer days. Instruct the patient to stimulate the pellet mildly for 3 to 5 seconds about 3 to 5 times a day or see if an attendant or family member can do so. The ear is an extremely powerful vortex of energy, yet auricular acupuncture is relatively gentle, well accepted, easy to learn and administer. Remember to remove or provide written instructions for the patient or the caregiver to remove the pellets within 3 to 5 days to guard against infection or if the pellet becomes uncomfortable to the patient, or plan to return to the nursing home to do this yourself.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree