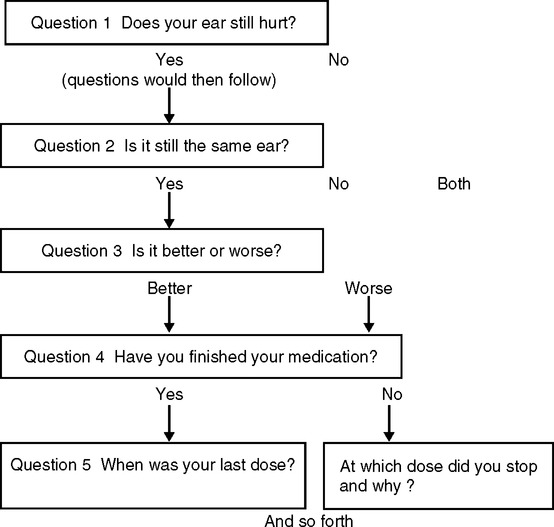

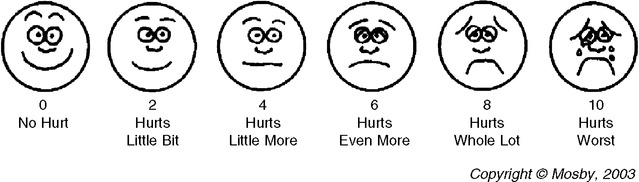

Upon successfully completing this chapter, you will be able to: • Differentiate between open-ended questions and closed-ended questions and give examples of both. • Contrast reflecting and clarifying and give examples of both. • Explain the importance of clarifying in an interview. • Give examples of leading the interview, and explain how this is different from asking leading questions. • Explain why silences should be encouraged in an interview. • Explain why summarizing information is important. • Explain the difference between hearing and listening To make gathering information easier, and to ensure that all necessary points are covered, some specialties develop algorithms for specific complaints (Fig. 3-1). An algorithm states an issue and offers paths to follow, depending on the patient’s answer at each step. For example, if the answer to a specific question is “yes,” a suggestion for the next question follows. If the answer is “no,” the next question follows a different pattern. This works well in some instances but may not allow for individual responses. An algorithm system may be too focused for individual patients, or too general for a focused interview. However, even the most inadequate algorithm at least leads in a general direction of questioning that the physician prefers. Another tool to help with a preset plan, and to cover as much necessary information as possible, is the use of acronyms. An acronym is a simple phrase or word with a question coordinated for each letter. Acronyms are easy to remember. Questions may be either general or specific, with additional questions added based on each answer you receive. For example, Box 3-1 shows an acronym—MDVISIT—that could be used for a routine physician’s office visit. As the patient answers each question, remember that even the best acronym or algorithm will not replace your responsibility to adjust your questions based on what you see or hear during the time you spend with the patient. Talking with patients to determine a current history requires most of the following points: • “Can you describe the ….(pain, sensation, bleeding, etc.)?” • “How long has this been bothering you (or going on, etc.)?” • “What happened to cause you to ask for help? Did it get worse, bother you more, etc?” • “Has it happened in the past? What did you do about it that time?” • “Does anything make it better or worse?” • “Have you taken anything?” or “What are you taking?” The following suggestions should help make each exchange of information more effective: • Before you begin, review the patient’s chart. Knowing the patient’s background and medical history shows that you are interested and concerned and gives you an idea of the questions you should ask. • Sit in a comfortably relaxed and open position; crossed arms transmit rejection, rigid posture is intimidating, and slouching is unprofessional. • Sit at the patient’s level, face-to-face. If it is culturally acceptable to the patient, maintain eye contact. • Show your interest by appropriate facial and nonverbal expressions, such as smiling and nodding. • Listen attentively and stay centered on the conversation. Patients are aware when you are not listening. • Start with general questions, such as “How may we help you today?” and work toward more probing questions. Working from simple to complex gives you time to establish rapport and builds the information background. • Phrase your questions to require an extended response in the patient’s own words, unless you need specific information. This is called open-ended questioning and requires that patients form answers in their own words. Closed-ended questions require brief, specific answers. (See “Getting to the Point,” later in this chapter, for further discussion of these concepts.) • Remember incongruence? Look for cues that conflict with the patient’s statements of concern. What is actually bothering this patient? There may be much more to discover than the initial or presenting complaint. • Remember that many responses are subjective, or obvious only to the patient; for example, pain to one patient may be discomfort to another. A small amount of blood to one patient may be hemorrhage to another. Closed-ended questions help clarify responses, such as exactly how much blood, or registering pain on a scale of 1 to 10 (Fig. 3-2).

GATHERING INFORMATION: LEARNING ABOUT THE PATIENT

GATHERING INFORMATION

SETTING THE STAGE

Because pain perception is subjective and varies significantly from one patient to another, pain assessment tools help make documentation reasonably simple. Although there are patients who tolerate high levels of pain with few complaints, and highly reactive patients who confuse discomfort with pain, scales such as this one help maintain a level of consistency and conformity in recording reports of pain. (Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale. In Wong DL, Hockenberry-Eaton M, Wilson D, Winkelstein ML, Schwartz P. Wong’s Essentials of Pediatric Nursing, 6th ed. St. Louis, Mo, Mosby, 2001, p. 691.)![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

GATHERING INFORMATION: LEARNING ABOUT THE PATIENT

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue