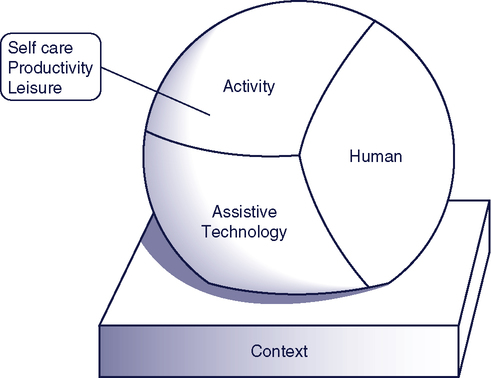

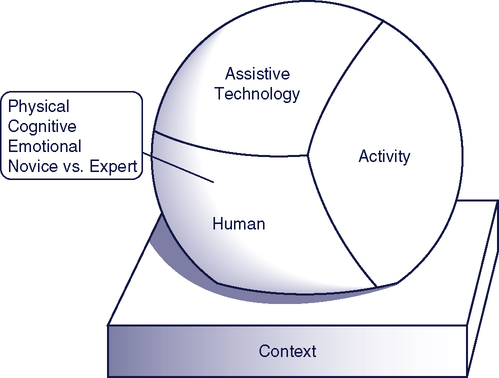

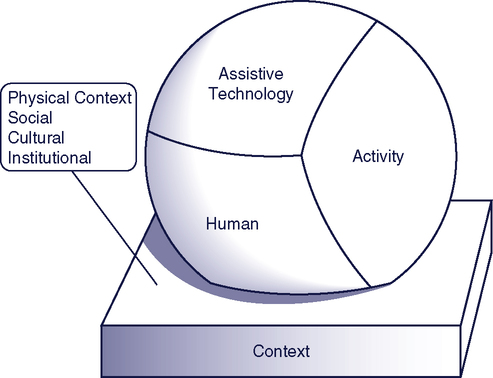

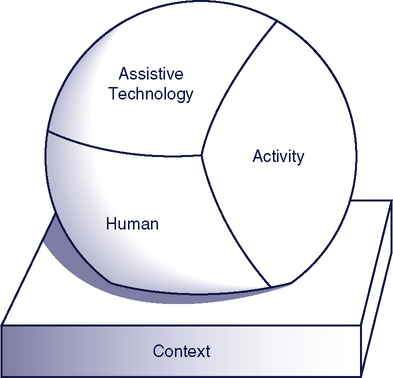

Upon completing this chapter you will be able to do the following: 1. Describe the components of an assistive technology system 2. Describe and discuss the Human Activity Assistive Technology (HAAT) model 3. List the major performance areas in which assistive technology systems are applied 4. Discuss the contexts in which assistive technologies are used 5. Delineate the major considerations in designing an assistive technology system 6. Describe the application of the HAAT model in the process of designing an assistive technology system In Chapter 1 we defined an assistive technology device as “an item, piece of equipment, or product system … that is used to increase, maintain, or improve functional capabilities of individuals with disabilities” (Public Law 100-407). In this chapter we build on this base by defining an assistive technology system as consisting of an assistive technology device, a human operator who has a disability, and an environment in which the functional activity is to be carried out. In this chapter we formalize this concept of a system and lay the groundwork for applying it to specific applications in later chapters. Before we describe a model that guides the selection and evaluation of assistive technology, two generic models will be presented that provide a foundation for one specific to assistive technology. These models are the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (2001)37 and the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E).33 Both of these models include elements of the person, an activity, and the environment to understand a specific construct (health domains and health-related domains in the first instance and occupational performance in the second). The ICF was described in more detail in Chapter 1. The ICF was derived from the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Disability and Handicap (1980),36 with the addition of environmental factors and use of more inclusive language being two main distinctions between the two versions. It “provides a description of situations with regard to human functioning and its restrictions and serves as a framework to organize this information.”37 Two components comprise factors of health and healthrelated states: body structures and functions, and activities and participation. The framework includes two contextual factors: environmental and personal factors. The term “body functions” refers to the functions of various systems in the body such as vision, sensation, and movement. Body structures include the anatomical structures that support the body functions (e.g., nerves, organs, and bones). Activity refers to the performance of a task or action by a person, while participation involves performance of the activity within an individual’s life roles or situation.37 The environmental context includes elements related to the physical, social, attitudinal, and institutional components. Finally, the personal factors include aspects such as age, sex, and lived experiences that have the potential to affect activity and participation.37 Another model that is useful for understanding the relationship between the person and their activity and environment is the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (CMOP),10 which was revised as the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E) in 2007.33 It conceptualizes the relationship between these three elements and their combined influence on occupational performance (the choice, organization, and satisfactory completion of daily activities) and engagement in occupations, which is defined as the choice, organization, and satisfactory completion of daily activities.10 Components of the person factor include physical, affective (emotional), and cognitive elements. Occupation is composed of self-care, productivity, and leisure; while the environment consists of physical, social, cultural, and institutional elements. The dynamic interaction of these elements influences an individual’s performance in chosen or required occupations.10 Both of these models are similar in that they include elements of the person, his or her activities, and environment. The ICF mentions assistive technology as an aspect of the environment, specifying products and technology for personal use in daily living for purposes such as personal indoor and outdoor mobility and transportation, communication, education, employment, and culture, recreation, and sport.37 It is not specifically mentioned in the CMOP. These models are useful in understanding assistive technology because they identify factors that affect participation in daily activities across the lifespan. However, they are limited as the role and considerations of assistive technology are not specified. A model is now presented that explicitly includes assistive technology as a component of the completion of daily activities. This model is intended to be used as a framework for the selection, implementation, and evaluation of assistive technology systems. The human activity assistive technology (HAAT) model is proposed as a framework for understanding the place of assistive technology in the lives of persons with disabilities, guiding both clinical applications and research investigations. The model has four components—the human, the activity, the assistive technology, and the context in which these three integrated factors exist. The human component includes physical, cognitive, and emotional elements; activity includes self-care, productivity, and leisure; assistive technology includes intrinsic and extrinsic enablers; and the context includes physical, social, cultural, and institutional contexts. Each of the components shown in Figure 2-1 plays a unique part in the total system. Consideration of each of these elements and their interaction is necessary for the design, selection, implementation, and evaluation of appropriate assistive technology and for research into various aspects of assistive technology development and use. The characterization of the model—with the elements of human, activity, and assistive technology forming a collective that is nested within a physical, social, cultural, and environmental context—is intended to show the dynamic interaction between the initial three factors and the pervasive influence on them, both individually and collectively, of the various contexts. The interaction among the components of the HAAT model can be illustrated through application to our case study of Marion. The activity is the fundamental element of the HAAT model shown in Figures 2-1 and 2-2 and it defines the overall goal of the assistive technology system. The activity is the process of doing something, and it represents the functional result of human performance. Activities are carried out as part of our daily living, are necessary to human existence, can be learned, and are governed by the society and culture in which we live.10 [A]ctivities … of everyday life, named, organized, and given value and meaning by individuals and a culture. Occupation is everything people do to occupy themselves, including looking after themselves … enjoying life … and contributing to the social, and economic fabric of their communities. …2,10 Activities are categorized in three basic performance areas: activities of daily living, work and productive activities, and play and leisure.10 Activities of daily living include dressing, hygiene, grooming, bathing, eating, personal device care, communication, health maintenance, socialization, taking medications, sexual expression, responding to an emergency, and mobility. Included in work/productive activities are home management activities, educational activities, vocational activities, and care of others. The play and leisure area includes activities related to self-expression, enjoyment, or relaxation. While these lists suggest that certain activities form specific categories, in reality the meaning an individual gives to an occupation determines in which performance area it is placed.10,25 For example, gardening may be a productive activity for one person and a leisure activity for another. Further, the meaning of an activity may vary depending on the role the individual assumes at the time the activity is performed. Christiansen and Baum (1997)12 define roles as “positions in society having expected responsibilities and privileges” (p. 54). The model in Figure 2-1 represents someone doing something someplace. Who is doing it? The individual with a disability is “operating” the system. Figure 2-3 highlights the human component of the HAAT model. Two theoretical approaches are useful when considering the human operator and his or her ability to use assistive technology: (1) the conceptualization of the person from the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (CMOP)10 and (2) occupational competence.24 The CMOP conceptualizes human abilities as comprised of three elements: physical, cognitive, and affective.10 Physical abilities include strength, coordination, range of motion, balance, and other physical properties. Cognitive components include attention, judgment, problem solving, concentration, and alertness, while affect includes emotional elements. It is important to understand a person’s abilities in each of these areas as they relate to the use of the desired technology. An appropriate match is needed between the person’s abilities and the requirements of the technology to ensure effective use.31 Where a mismatch occurs, devices will be misused or abandoned, as they do not meet the user’s needs. In the HAAT model, the motor outputs of communication, mobility, and manipulation are required in order to accomplish the goals defined by activities. These three areas require that the human operator possess motor output skills as well as sensory function to perform these activities. These are akin to the physical domain of CMOP. For example, visual or auditory input is typically required for communication. If these skills are impaired, assistive technology systems can provide assistance by requiring different skills. For example, when a hearing aid compensates for reduced hearing thresholds or a Braille output system avoids the need for visual reading, the assistive technology provides replacement or augmentation of a sensory system. Finally, central processing is required for the successful completion of activities. Components of central processing include perception, motor control, and cognition, similar to the CMOP cognitive domain. If the human’s capabilities are limited, then assistive technology systems can often provide assistance in this area as well. For example, procedures for device operation may be simplified for an individual who experiences difficulty in sequencing tasks, or recall aids may be incorporated to assist someone who has memory deficits. Psychological function (referred to as “affect” in CMOP) influences performance of activities, for example, through motivation, self-efficacy, and perception of the value of the activity. These human performance components of the HAAT model are examined in detail in Chapter 3. Occupational competence gives a dynamic context to the understanding of human abilities and how a person changes and adapts their engagement in activity in response to environmental demands and changes in their own abilities. While CMOP is useful to conceptualize human behavior at a given point in time, occupational competence helps understand behavior across the life span. Five constructs are important to the notion of occupational competence.24 Capacity refers to the potential skill, ability, or knowledge that an individual can apply to a given activity. Capacity changes with development and aging, as well as with trauma or illness. Effectance is the extent to which the individual reaches or uses their capacity in a given task. When a person is motivated to perform well in an activity, effectance approaches capacity. Affordances are those environmental elements that can facilitate performance of a task, providing the individual perceives them as a facilitator. Self-efficacy is a well-known concept described by Bandura (1977)5 that refers to an individual’s belief that they can be successful in a particular situation. Finally, competence is the selfperception of satisfactory performance as compared to some defined standard. Collectively, these constructs contribute to occupational competence, i.e., the ability to meet the demands that are required for successful engagement in various life roles.24 Thus, expectations by and of the individual, relative to performance of an activity, change as the person grows and acquires new skills, or conversely, as they age or experience illness or trauma and lose skills. This notion of occupational competence illustrates the dynamic elements of physical and cognitive capacities and how they are influenced by the individual’s attitudinal and motivational characteristics to meet the demands of various life roles. We can distinguish between a person’s skill and his or her ability. An ability is a basic trait of a person, what a person brings to a new task, whereas a skill is a level of proficiency, which is comparable to “effectance” as described by Matheson and Bohr (1997).24 In assistive technology applications, this distinction is important. It is usually possible to obtain an assessment of a person’s abilities, but it is difficult to predict the level of skill that she will develop using the technology. Ability can also mean transferring a skill from a related area and applying it to a new task. For example, a person with a disability might develop skill in the use of a joystick as a computer interface and then transfer this motor skill to the use of a power wheelchair. In this type of situation, the acquired skill in the first task becomes an ability that can be used in the second task. In Chapter 1 we defined soft technologies as “the human areas of decision making, strategies, training, and concept formation.” In particular, strategies are part of the human skills required for the success of an assistive technology system. As Enders (1999)15 has pointed out, people who have disabilities use strategies to complete tasks. These can often either replace assistive technologies completely or compensate for deficiencies in the technology. For example, Marion uses strategies to enhance her augmentative communication system functionality. She may wave instead of typing “hi,” or at times she may use pre-stored words to increase her speed and spell at other times to increase the participation of her communication partner. As in other aspects of the assistive technology system, the strategies used are highly dependent on all the other aspects of the assistive technology (AT) system. The context determines which strategies are important and useful; the characteristics of the technology affect which strategies are important to success; and the activity dictates the choice of strategies. Enders has proposed that strategies make up one side of a three-pronged approach to assistive technology applications that she calls “a human accomplishment support system.” This framework is consistent with the HAAT model. The other two aspects of the framework are personal assistants and assistive technology devices. Over the past several decades the models used to describe disability and the disablement process have changed dramatically.29 In the 1950s the focus was on the disabled person’s “problem” of an inability to participate in work, play, education, and daily activities of living; this problem was “in the person”; that is, it was strictly the result of the impairment. More recently, there has been an increasing awareness that the difficulties experienced by individuals with disabilities result as much from environmental factors as from the impairment itself. Initially the focus was on the physical or built environment, with much effort to make curb cuts, install elevators, and so on. As individuals with disabilities began to participate more fully in society, it became evident that the social and attitudinal barriers were just as great as the physical ones. A “minority group model” of disability emerged in which the attention was shifted away from the impairment to the social, political, and environmental disadvantages forced on people who have disabilities.9 Bickenbach et al. (1999) conceptualized disability in a different way.6 In their view, disability was a universal experience if a person lives long enough. Contrary to the minority group model, which advocated for special status for individuals with disabilities, the universalism concept advocated for broader social justice and policies that were more inclusive of persons with disabilities, actions that would benefit a broader segment of society. With these new perspectives, problems of societal participation were no longer attributed to the impairment of the person with a disability. Rather, lack of participation in society was viewed as resulting from limitations in the social and physical environments. The emphasis on participation in ICF is indicative of the move away from a “problem in the person” concept to a “problem in the environment” model. In the HAAT model we have captured these external influences in the context. As shown in Figure 2-4, the context includes four major considerations. These are (1) the physical context, including natural and built surroundings and physical parameters, (2) the social context (with peers and with strangers), (3) the cultural context, and (4) the institutional context including formal legal, legislative, and socio-cultural institutions such as religious institutions. The contexts in which the human carries out the activity can be determining factors in whether the person successfully uses an assistive technology system. The supports and barriers in these environments are important considerations in the selection and evaluation of these systems. One further distinction is important in the consideration of context, which is the level of the environment. Three levels of environments have been described in the literature: microenvironment, meso environment, and macro environment.17,22 The microenvironment refers to the closest, most intimate environments in which a person functions, such as their home, school, or work setting. Here the person and their abilities are known, roles are defined and rules and expectations are understood. The meso environment describes those settings in which a person functions less frequently and includes various community facilities such as community centers, shopping malls, and churches. The macro environment refers to the broader social and cultural contexts that impose a legislative and moral behavioral framework on the person.22 Each of these environments influences the use of assistive technology systems. It is important to understand how each aids or hinders the use of assistive technology. Ambient sound (including noise) can have a major effect on the intelligibility of voice synthesizers or voice recognition systems. Sounds generated by devices such as printers, power wheelchairs, voice output communication aids, and auditory feedback from computer programs can be disruptive in a classroom. Church and Glennen (1992)13 discuss ways of controlling sound and lighting to avoid interference in the classroom while still facilitating the functional gains provided by the assistive technology.

Framework for Assistive Technologies

Human performance and assistive technologies

Foundation for a Human Activity Assistive Technology Model

A Human Activity Assistive Technology Model

The activity

The human

Skills and Abilities

The contexts

Physical Context

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine