I. FRACTURES OF THE TIBIAL PLATEAU1–4

A. For practical purposes, fractures of the tibial plateau are classified as follows:

- Undisplaced (a vertical fracture of the plateau)

- Split (a split fracture with displacement, with or without slight comminution)

- Depressed (centrally depressed fracture)

- Split and depressed with an intact tibial rim

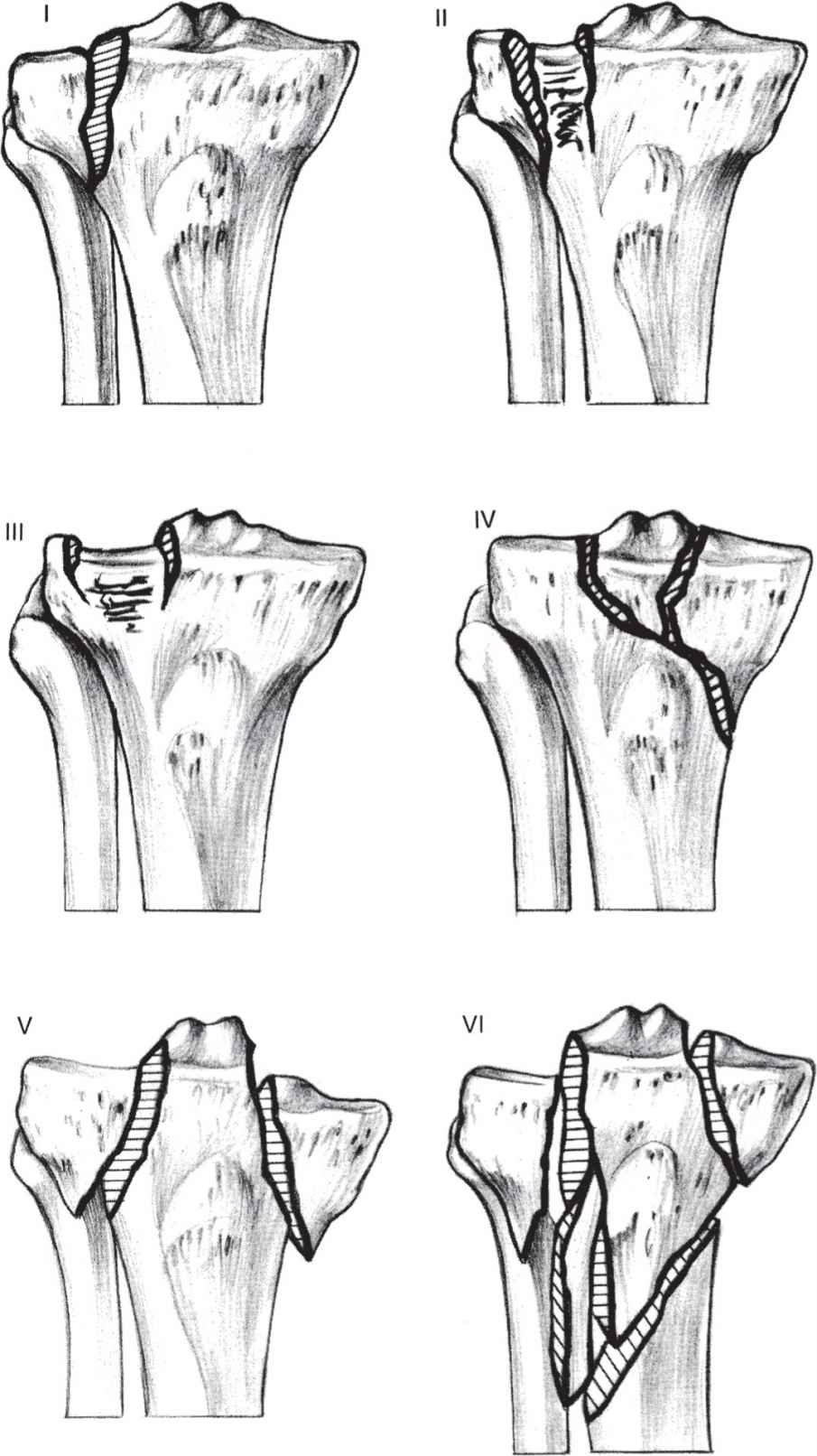

- Any of 1 through 4 with metaphyseal or even diaphyseal extension. The elements of these descriptions are contained within Schatzker system (Fig. 26-1).

Figure 26-1. Schatzker’s classification system. I: split; II: split with depression; III: depression; IV: medial condyle; V: bicondylar; VI: bicondylar with shaft extension. (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic Trauma Protocols. New York, NY: Raven; 1993:315, with permission.)

B. Examination is different from that for other knee injuries. It is wise to carry out a definitive examination only after roentgenographs have been obtained. Differential diagnosis includes a major ligamentous injury or knee dislocation.5–7 The examination should include inspection for wounds, evaluation of the distal circulation (pulses and capillary refill), and neurologic (motor or sensory) function. Motion and stability should not routinely be assessed in these injuries; however, this type of injury can be associated with ligamentous or meniscal damage.1

C. Radiographs. Oblique films in addition to the routine anteroposterior and lateral radiographs are often helpful in identifying fracture lines and articular displacement. Computed tomography demonstrates minor fractures and accurately depicts the degree of depression of the tibial plateau; axial cuts with sagittal reconstruction are the routine.

D. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful when there is clinical concern for associated ligamentous injury. The incidence of complete ligamentous or meniscal disruption associated with operative tibial plateau fractures on MRI has been reported as high as 99% in one follow up study. In split-depressed fractures, depression was greater than 6 mm and widening was greater than 5 mm, predicted lateral meniscal injury in 83% of fractures, compared with 50% of fractures with less displacement (P < .05). Increasing displacement can also be associated with cruciate ligament injuries and lateral collateral ligament injuries in almost 30% of patients.

- Undisplaced fractures. In some settings, especially when multiple injuries are involved, fixation with two percutaneous cannulated cancellous lag screws is advisable to ensure maintenance of reduction. For isolated injuries, generally nonoperative management is selected. A splint is applied, and the leg is elevated for the first 24 to 48 hours. Knee aspiration is carried out if a significant hemarthrosis is present, and knee motion may be started with continuous passive motion (CPM) if available. As soon as the patient is comfortable and the range of motion is increasing, he or she can be followed up as an outpatient. Follow-up radiographs should be obtained shortly after motion is instituted to ensure that the fracture remains nondisplaced. Touch-down weight bearing should be maintained for 8 weeks to prevent displacement from shear forces.

- Displaced fractures

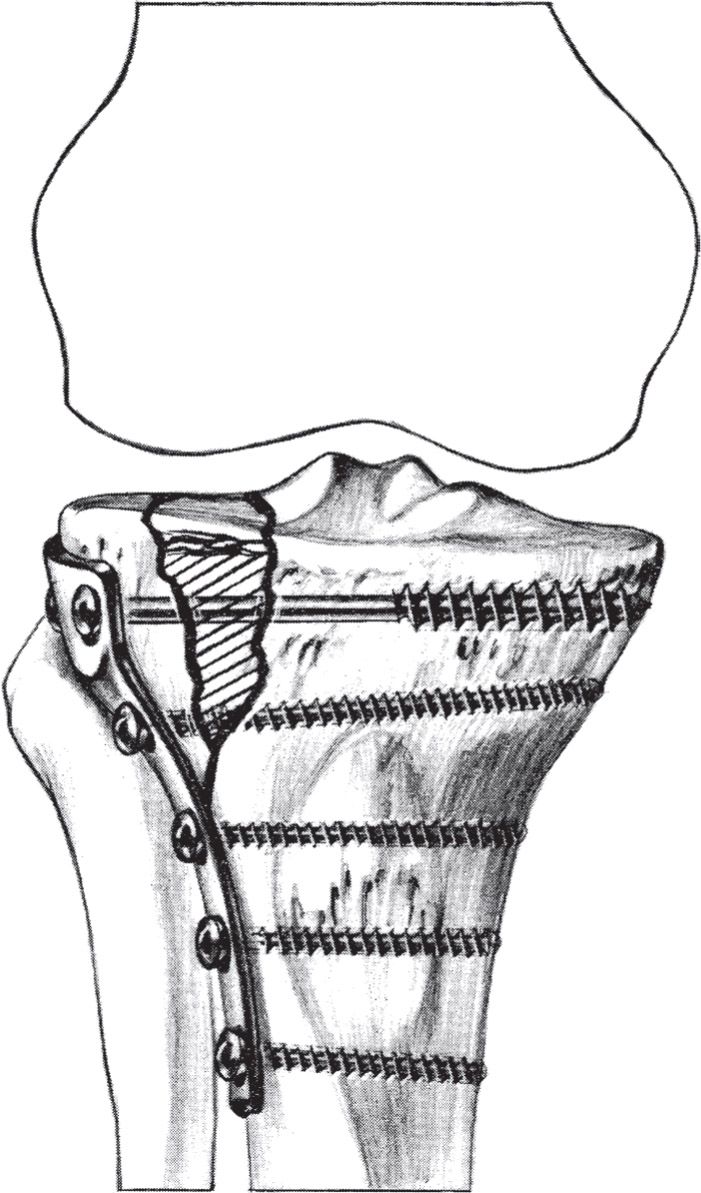

a. Split fracture. Open reduction and fixation is generally done if there is a significant widening (lateral or medial displacement of more than 3 to 5 mm) of the plateau.8,9 The internal fixation must be rigid enough to allow movement of the joint as soon as there is soft-tissue healing. In this situation, the authors prefer to use the Association of the Study of Internal Fixation (ASIF) buttress plate (Fig. 26-2) or a dynamic compression or locking plate when the patient is osteoporotic.4 Recently, there has been a move toward use of smaller implants for all tibial plateau fixation. Specialized 3.5-mm T- and L-buttress plates allow the placement of more screws under the articular surface. If the patient is young and has dense bone, multiple percutaneous cannulated lag screws can be inserted under fluoroscopic and/or arthroscopic control. Percutaneous placement of a large reduction clamp is often successful in providing reduction of the fracture. If open reduction and internal fixation are not feasible, treatment should be as for comminuted fractures.

Figure 26-2. Internal fixation of a split depression fracture of the tibial plateau using L-buttress plate fixation with bone grafting of the elevated segment. (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic Trauma Protocols. New York, NY: Raven; 1993:318, with permission.)

b. Central depression of the plateau. If depression is greater than 3 to 5 mm, especially with valgus stress instability of the knee greater than 10° in full extension, most authors currently recommend elevation with bone grafting and fixation.2,3,9,10 More recently, articular reductions have been done with arthroscopic visualization with percutaneous technique for elevation of the segment. Autogenous bone graft has typically been the treatment of choice, but allograft and cancellous substitutes such as corallin hydroxyapatite and calcium-phosphate cements have been successfully used.9 Randomized trials comparing calcium-phosphate cements and to controls have suggested that use of calcium-phosphate bone cement for the treatment of fractures in adult patients is associated with a lower prevalence of pain at the fracture site in comparison with the rate in controls (patients managed with no graft material). Loss of fracture reduction is also decreased in comparison with that in patients managed with autogenous bone graft. Generally, percutaneous lag screws are adequate for support of the elevated joint surface and bone graft or graft substitute material.

c. Split-depressed fractures with a displacement/depression of more than 3 to 4 mm are treated with reduction, fixation, and early motion in most young patients. Generally, this reduction is done with an open technique with an anterior or anterolateral approach, elevation, and bone grafting using buttress or locking buttress plates for older patients (Fig. 26-2) and lag screws or 3.5-mm small fragment T- or L-plates or one-third tubular plates (as washers) in younger patients. These fractures may be managed with arthroscopic reduction in skilled hands. Secure fixation is critical so that early motion with or without CPM can be initiated. Patients are generally limited to touch-down weight bearing for 12 weeks to prevent late fracture settling. If the patient’s limb is stable to varus and valgus stress in an examination under anesthesia shortly after injury, traction treatment with a tibial pin and early motion is an option.10,11 The patient is placed in a cast-brace (as described in Chapter 8, III.H) or a hinged knee brace after 3 to 4 weeks.1 This treatment is not currently recommended on a routine basis. If the instability exceeds 10°, reduction and fixation as described earlier is indicated.11

d. Fractures with metaphyseal/diaphyseal extension are treated similarly to split-depressed fractures if the joint extension is significant. Generally, buttress plate fixation and bone grafting are required. When the injury is bicondylar, stripping the soft tissues off both condyles from an anterior approach should be avoided; this results in a high incidence of nonunion and deep infection. Instead, the most unstable condyle (usually lateral) is selected for the buttress fixation via an anterolateral approach and the other condyle is stabilized by percutaneous screw fixation, fixation with a posterior medial incision and small buttress plate, or neutralization with an external fixator for 4 to 6 weeks while motion is limited. With all tibial plateau fractures treated with operative stabilization, it is important to examine the knee for ligamentous stability after completing the fixation in the operating room to rule out ligamentous injury (see II.B).1 The functional results of treatment are often better than the routine radiographs seem to predict. Early motion of the knee joint and delayed full weight bearing are the keys to the maximum restoration of joint function.2–4

- Apply a cast-brace (as described in Chapter 8, III.H) off the self-hinged knee braces, which are lightweight and limit varus and valgus stress and are more widely used. The same ambulation protocol, touch-down weight bearing, is followed.

- In special situations, the patient is placed in a long-leg cast until the fracture is healed. Then the patient is placed in a rehabilitation program to regain full extension and flexion of the knee to beyond 90°. The patient is kept on protected weight bearing for at least 3 to 4 months. This treatment is generally limited to patients with a severe neurologic condition or significant osteopenia.

E. Complications

- Significant loss of range of motion may occur, particularly if early movement is not instituted.

- Early degenerative joint changes with pain can occur regardless of the degree of joint reconstruction. In some instances, the pain may be severe enough to require arthroplasty or arthrodesis.8

- The infection rate following operative treatment is reduced in experienced hands. Most infections occur because of excessive soft-tissue stripping.

- Nerve and vascular injuries that occur at the time of injury or subsequent to treatment are not uncommon.12 Nerve injuries are usually traction injuries, and recovery is unpredictable. Compartmental syndrome may be present and should be treated as described in Chapter 3, III.

II. EXTRAARTICULAR PROXIMAL TIBIAL FRACTURES

A. Classification. Proximal tibial fractures are classified similar to diaphyseal fractures (see III.C).

B. Examination. Initial examination should be comprehensive including inspection, palpation, and lower extremity neurovascular assessment. The integrity and condition of the soft tissues should be carefully inspected. The alignment of the lower extremity should also be noted. The compartments of the leg should be palpated and passive flexion and extension of the toes performed to assess for pain and possible compartment syndrome. Distal pulses may be palpable despite ischemia from increased compartment pressure. Definitive diagnosis may require measurement of intracompartmental pressures (see Chapter 3, III). The diagnosis of a compartment syndrome is a surgical emergency and requires prompt release of pressure to preserve muscle and nerve viability. A careful examination of the extremity pulses is imperative to rule out potential vascular injury.

C. Radiographs. Although a tibial diaphyseal fracture may be obvious from clinical examination, anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the tibia (including the knee and ankle joints) are needed to plan management. Radiographs should be carefully reviewed to ensure fracture lines do not reveal intraarticular extension. Computed tomograms or plain tomograms can be helpful to identify intraarticular extension when plain X-rays are difficult to interpret.

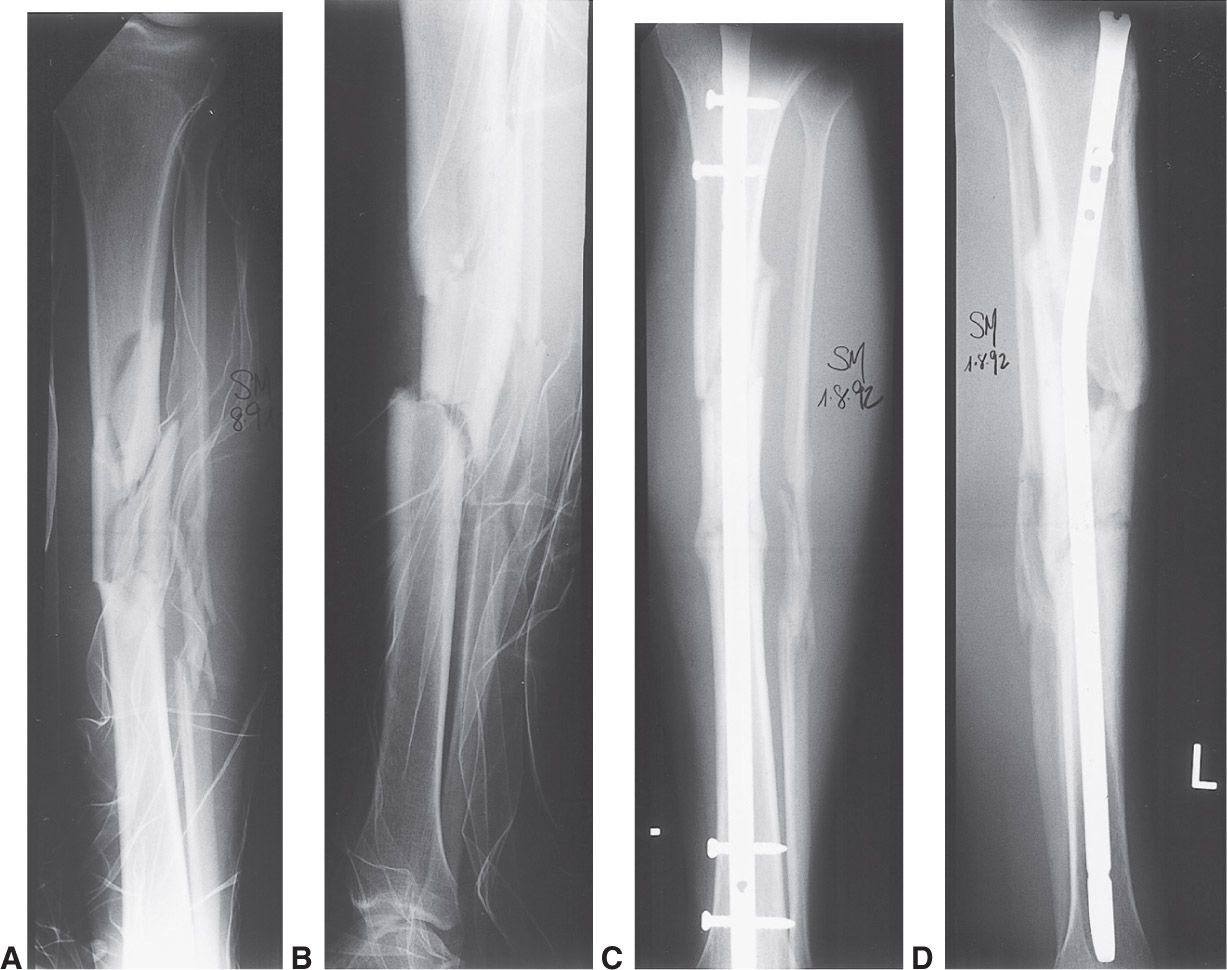

Figure 26-3. Displaced closed fractures of the tibia shaft, when shortened more than 1 cm or considered to be unstable, are best treated with interlocking nails. A,B: Preoperative radiographs of a shortened, unstable segmental fracture of the tibia shaft. C,D: The interlocking nail in place. The screws placed through the holes in the nail proximal and distal to the fracture provide length and rotational stability for the fracture. Nearly all fractures of the femoral shaft in skeletally mature individuals are treated with similar interlocking nails, allowing mobilization of the patient and early range of motion of adjacent joints.

D. Treatment. Extraarticular proximal tibial fractures are often the result of high-energy trauma with displacement and comminution. Most authors agree that operative management of such fractures is warranted to optimize patient outcomes. However, it remains unclear which surgical option (plate, nail, external fixator, or combination) is preferable. The rates of nonunion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree