I. PELVIC RING DISRUPTIONS

Pelvic ring disruptions are a common cause of death associated with trauma, with head injuries being the most common cause.1–3 Approximately two-thirds of pelvic fractures are associated with other fractures and injuries to soft tissues. The fatality rate from pelvic hemorrhage with current management techniques ranges from 5% to 20%.4,5 If a patient presents with signs and symptoms consistent with shock, the mortality rate increases to 57%.6 In the acute setting, early mortality in patient with pelvic fractures occurs as a result of hemorrhage. Multisystem organ failure is the more common cause of death in the subacute setting (after 24 hours).7

II. PELVIC ANATOMY AND STABILITY

The pelvis is a ring that consists of the bony architecture (sacrum, ilium, ischium, and pubic) and ligaments that provide rotational and vertical stability. The anterior pelvic ring provides approximately 40% of the stability. Disruption of the pubis symphysis and the pelvic floor (sacrospinous, sacrotuberous) ligaments will result in rotational instability. The posterior pelvic ring provides 60% of the stability. Disruption of the posterior bone–ligamentous complex can result in vertical instability. A stable pelvis can be defined as one that will withstand normal physiologic forces without abnormal deformation (mobilization without significant displacement or deformation).8

Most pelvic ring injuries are stable fractures that can be treated nonoperatively with protected weight bearing and early mobilization. The stable pelvic fractures are often low-energy mechanism, such as a fall from a standing height in an elderly patient, and are usually isolated injuries. The unstable pelvic fractures are less common, but they raise greater concern because of the increased morbidity and mortality associated with them. Unstable pelvic fractures are often a result of high-energy injury such as motor vehicle accident or fall from significant height. Patients with unstable pelvic fracture are often polytrauma patients presenting with associated head, chest, abdomen, and extremity injuries. The pelvic fracture may require early temporary stabilization with an external fixator or pelvic binder as part of the resuscitation care and then definitive surgical fixation to provide stability and avoid deformity.

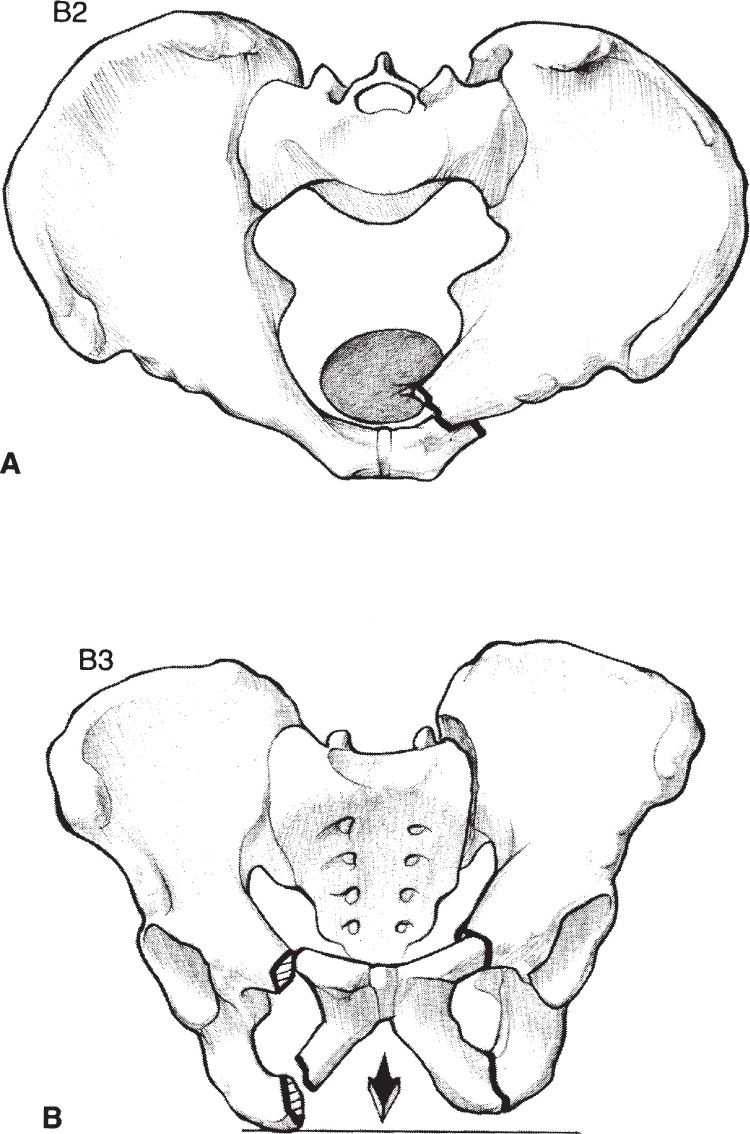

III. CLASSIFICATION OF PELVIC FRACTURES. Numerous systems have been proposed, but the Tile classification system is the most widely used.9 This classification is based on the stability and mechanism of injury. The Young–Burgess classification system has expanded on this work by adding a combined mechanism notion.1

A. Tiles Classification: Types

- Type A: stable

- Type B: rotationally unstable, but vertically and posteriorly stable

- Type C: rotationally and vertically unstable

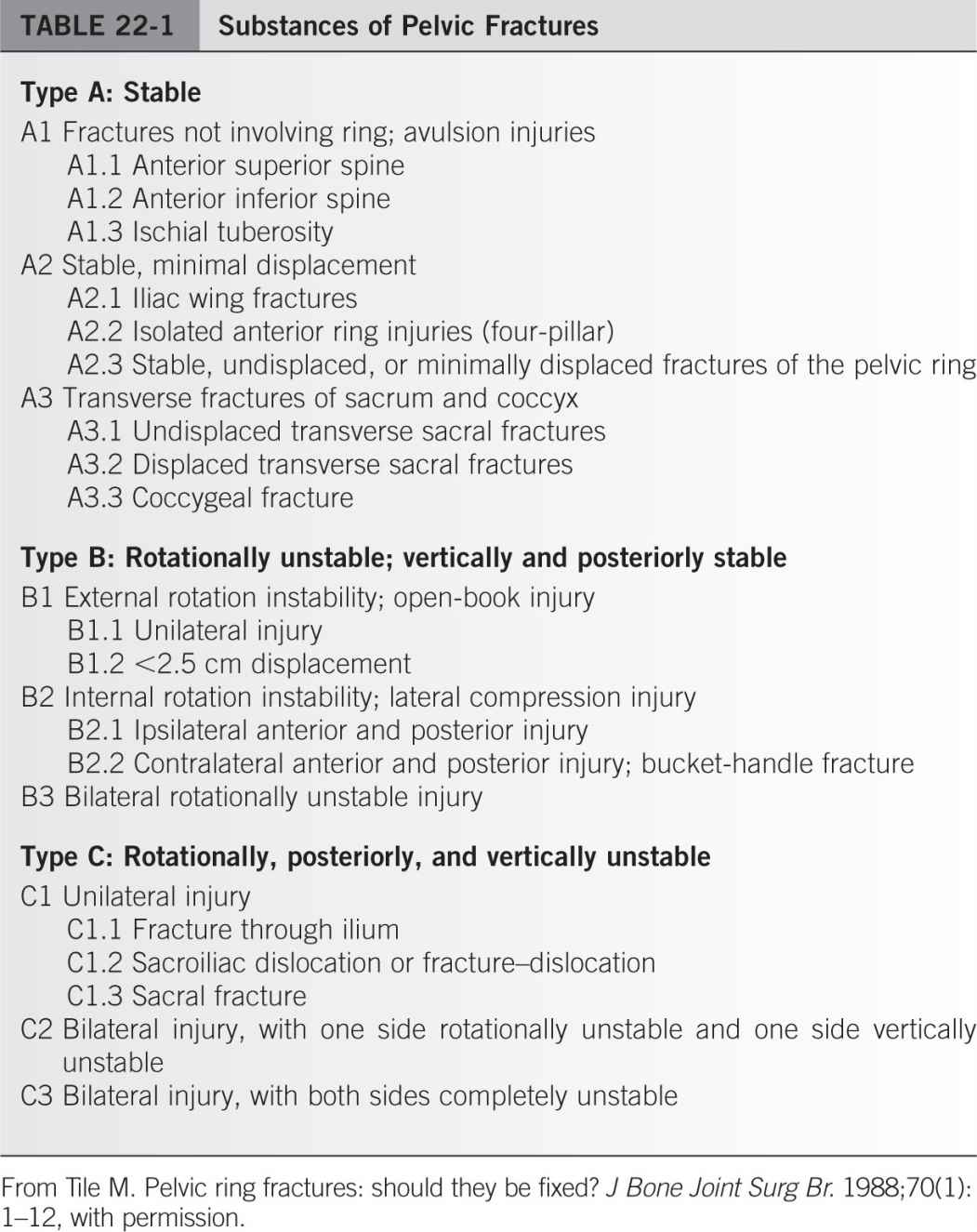

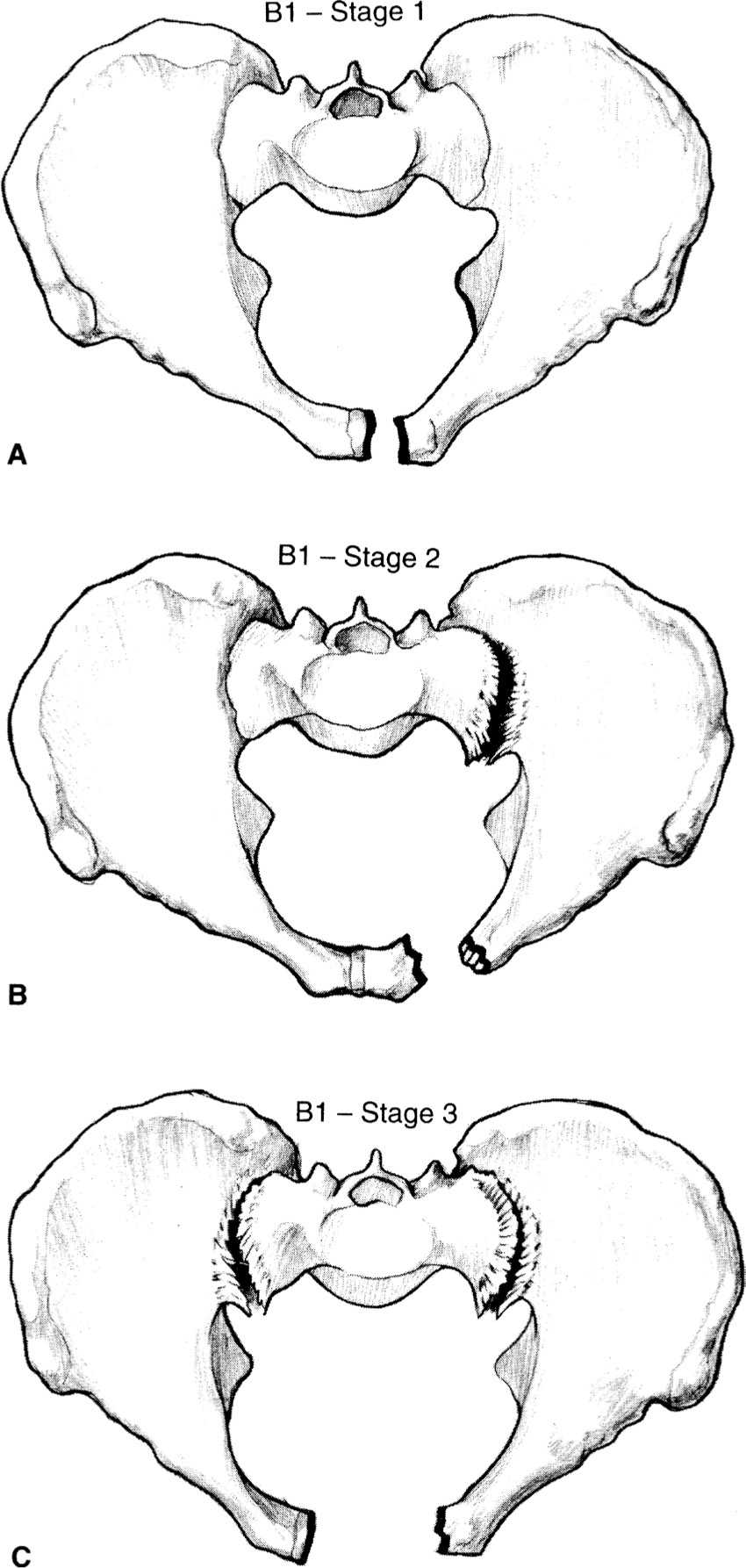

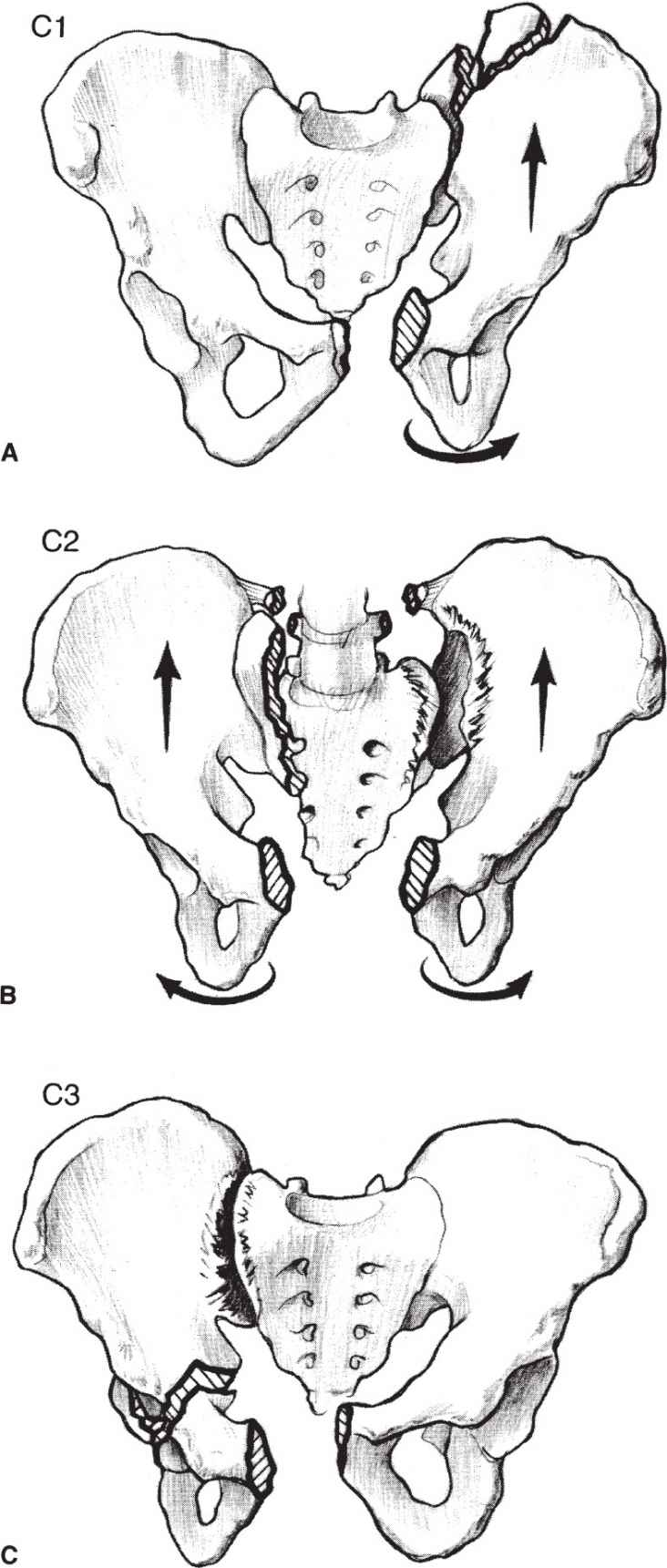

B. Subtypes that have important influences on treatment are presented in Table 22-1 and illustrated in Figs. 22-1 to 22-3.

Figure 22-1. A: Type B1, stage 1 symphysis pubis disruption. B: Type B1, stage 2 symphysis pubis disruption. C: Type B1, stage 3 symphysis pubis disruption. (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic Trauma Protocols. New York, NY: Raven; 1993:228, with permission.)

Figure 22-2. A: Type B2 lateral compression injury (ipsilateral). B: Type B3 lateral compression injury (contralateral). (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic Trauma Protocols. New York, NY: Raven; 1993:228, with permission.)

Figure 22-3. A: Type C1 pelvic injury. B: Type C2 pelvic injury. C: Type C3 pelvic injury. (From Hansen ST, Swiontkowski MF. Orthopaedic Trauma Protocols. New York, NY: Raven; 1993:229, with permission.)

C. Fractures of the acetabulum are discussed in Chapter 23.

D. Note for historical purposes that a Malgaigne fracture is a vertical fracture or dislocation of the posterior sacroiliac joint complex involving one side of the pelvis.

IV. ASSESSMENT AND EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT

A. Pelvic ring disruptions in a hemodynamically unstable patient require assessment per the advanced trauma life support protocol. It is important to identify life-threatening injuries, specifically ruling out other sources of hemorrhage. A multidisciplinary team approach has been shown to decrease mortality.8,10,11

- Pelvic fractures are suspected in patients presenting with pain, swelling, crepitus, or tenderness over the symphysis pubis, anterior iliac spines, iliac crest, or sacrum, but a good roentgenographic examination is essential for diagnosis. Correlation of the mechanism of injury with evaluation of the AP pelvis can help determine whether there is a stable or unstable pelvic fracture and risk of hemorrhage. Patients with these injuries are often unconscious or intubated, so the examination for pelvis or lower extremities deformity and open wounds is critical. Historically, manual stress examination for stability was recommended. However, recent studies identify poor sensitivity for identifying unstable pelvic fractures with stress examination.12

- Mandatory physical examination should include assessing the perineal region and performing a rectal, vaginal, and a neurologic evaluation. Despite the difficulties involved, a pelvic (in women) and rectal examination should be done to check for fresh blood, open wounds, perineal sensation in a conscious patient, a displaced unstable prostate, and sphincter tone. Open pelvic fractures historically have had high mortality rates up to 50%. However, in a recent review article, the rate has been reduced because of improved treatment to reduce hemorrhage, local infection, and sepsis.13 Pelvic fractures frequently are associated with neurologic damage, so a careful neurologic evaluation should be done in all patients.

- Signs of significant pelvic trauma are perineal ecchymosis, laceration, scrotal/labial swelling, flank ecchymosis, Morel-Lavallee lesion (soft-tissue degloving injury).14,15 Beware of associated injuries that include extremities fractures, neurologic deficit, urologic, gynecologic, and gastrointestinal systems.

B. Other specific studies. Patients with all but minimal trauma should have an indwelling urinary catheter for the dual purposes of measuring urine output while the associated shock is being treated and investigating possible bladder trauma. Urethral and bladder disruptions can be missed in up to 23% of pelvic fracture patients on their initial evaluation.16 If there is blood at the penile meatus, a retrograde urethrogram should be performed before passage of the catheter, which should be preformed by a consulting urologist.1,2 Cystogram should be performed if there is concern for bladder rupture (gross hematuria or increased red blood cell in the urinalysis).

V. PELVIC HEMMORHAGE CONTROL AND TEMPORARY STABILIZATION1,5

A. Symptoms and signs. At presentation, approximately 20% of patients with pelvic fracture are in shock. Severe backache can help differentiate the pain of retroperitoneal bleeding from the pain of intra-abdominal bleeding.

B. Resuscitation. Most causes of hemorrhage are adequately handled by rapid replacement and maintenance of blood volume, followed by reduction (when appropriate) and stabilization of the fractures. Adequate blood replacement is the first priority, and its effectiveness is monitored by the patient’s pulse, blood pressure, central venous pressure, and urine output. Blood loss of 2,500 mL is common, and blood replacement is usually necessary even without evidence of an open hemorrhage. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage is a useful test to rule out intra-abdominal injury at the site of hemorrhage if imaging studies are unavailable.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree