Fractures of the Coronoid

Bernard F. Morrey

INTRODUCTION

Unlike other topics, when to fix a coronoid fracture is a bit complex and requires a more detailed discussion. The fracture uncommonly exists as an isolated injury, so comments regarding the ligaments and radial head are in order.

COLLATERAL LIGAMENTS

I assume any coronoid fracture must cause some injury to one or both of the collateral ligaments. Hence, my exposure usually involves a posterior incision, from which I can inspect each ligament complex, as necessary. As discussed in the appropriate chapter on ligament injury, the lateral ligament must always be formally repaired; the medial ligament will typically heal if the ulnohumeral joint is reduced and stable (1).

RADIAL HEAD

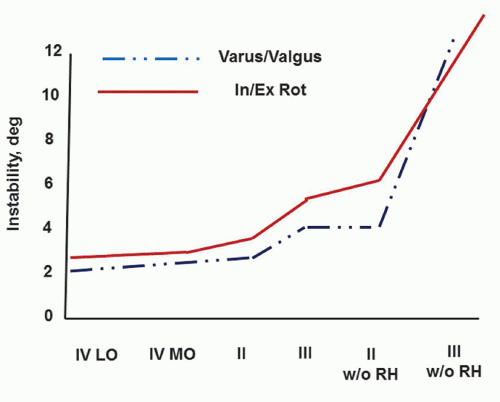

The radial head has long been known to be important to compensate for coronoid deficiency (2). It is this relationship that has emerged as the key as to whether the coronoid fracture needs be fixed (3,4). It has been shown the radial head constitutes 60 and the coronoid 40% of the anterior articular surface of the elbow (4).

When the radial head is present, and the collateral ligaments are intact, up to 50% of the coronoid may be absent and the elbow will remain stable (Fig. 7-1) (3,4). Hence, the value of either fixing the radial head fracture, if possible, or replacing the head with a prosthesis is clear in the face of these specific associated injuries. Procedures to address fractures of the radial head are discussed in detail in Chapters 5 and 6.

CORONOID

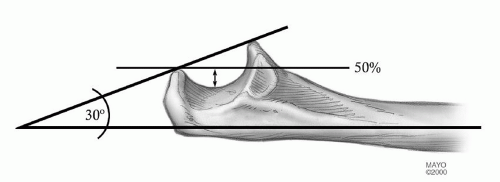

As noted above, the significance of a coronoid fracture is becoming somewhat clearer. It depends on the integrity of the ligaments and the radial head, but at least 50% of the process is required to have any possibility of adequate stability to be present. This can be estimated by a line drawn from the tip of the olecranon to the base of the fracture (Fig. 7-2). If this line is parallel to or anterior to the ulnar shaft, adequate stability is a possibility. I resolve this by an examination under anesthesia. Pay particular attention to rotatory stability, as the coronoid is especially important with these loading modes (3).

Classification

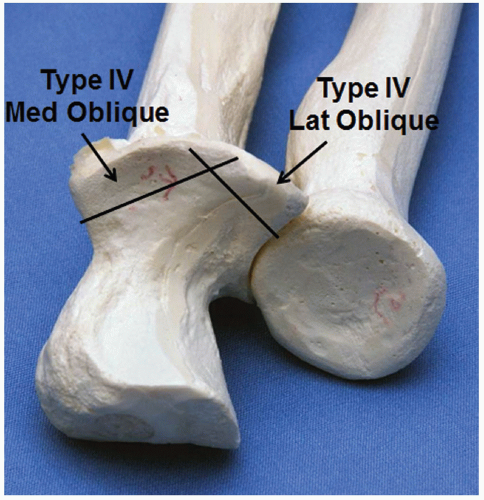

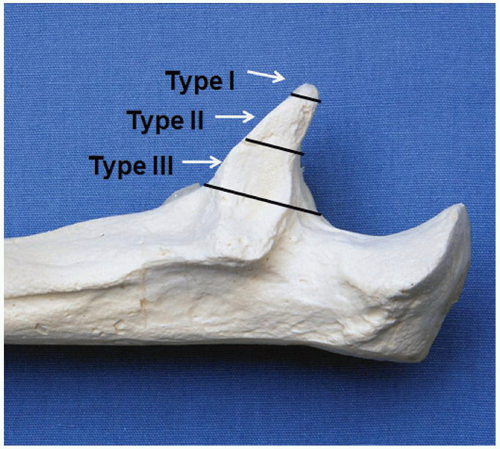

Regan and Morrey (5) have described three fracture types depending on the extent of the fracture (Fig. 7-3). As more experience has been gained with these fractures, it is now recognized that these fractures are more complex (6). Currently, the simple modification of the original classification includes medial and lateral oblique fractures (Fig. 7-4). However, it has been recently shown that for practical matters, the original classification system is probably adequate as a basis of our clinical decisions (7).

FIGURE 7-1 Data demonstrating that the elbow can potentially be stable with 50% coronoid deficiency if the radial head and collateral ligaments are competent. |

FIGURE 7-2 Coronoid 50% rule. A line from the tip of the olecranon and parallel to the shaft passes through 50% of the coronoid. |

FIGURE 7-3 Regan-Morrey classification of coronoid fractures. Some type II and all type III are unstable. |

Indications

Type l fractures need not be fixed.

Type II Fracture

In type II fractures, as much as 50% of the coronoid is involved, and the elbow is considered unstable unless proven otherwise. Examination under anesthesia is carried out. If posterior displacement occurs with less than 40 to 45 degrees of flexion, the residual articulation is considered inadequate and the ulnohumeral joint must be stabilized. If the fracture fragment is large enough for fixation,

osteosynthesis is performed. If the fragment is too small for fixation or is comminuted, then a plate may be used to stabilize and orient the fracture fragments, or if this is not possible, a heavy no. 5 suture is placed over the fragment (or fragments), which is brought to its anatomical location and tied through drill holes placed in the ulna. The rigidity and stability of the construct are then assured by the application of a hinged external fixator. The distraction device is maintained for 3 to 6 weeks, depending upon the nature of the injury (8) (see Chapter 12).

osteosynthesis is performed. If the fragment is too small for fixation or is comminuted, then a plate may be used to stabilize and orient the fracture fragments, or if this is not possible, a heavy no. 5 suture is placed over the fragment (or fragments), which is brought to its anatomical location and tied through drill holes placed in the ulna. The rigidity and stability of the construct are then assured by the application of a hinged external fixator. The distraction device is maintained for 3 to 6 weeks, depending upon the nature of the injury (8) (see Chapter 12).

Type III Fracture

These injuries are the most difficult to treat as, by definition, the ulnohumeral joint is grossly unstable. If the coronoid is a large fragment and has not been comminuted, it may be fixed with a screw or plate and screws and the joint will be stable. If comminuted, a stabilization plate is employed.

Indications for Fracture Fixation (1,9-12)

Type II fractures with an intact, fixed, or replaced radial head and in which the elbow is grossly unstable when flexed less than 50 or 60 degrees.

All type III fractures.

Isolated anteromedial coronoid fractures resulting in varus overload; these fractures have a propensity for articular incongruity, subluxation, and arthritis.

RELATIVE CONTRAINDICATIONS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree