9 Fracture management

Cases relevant to this chapter

Essential facts

1. Most displaced fractures must be reduced and stabilized, followed by rehabilitation to restore function.

2. Many fractures are suitable for non-operative treatment but major long bone fractures are usually treated surgically.

3. Periarticular fractures or intra-articular fractures that result in joint incongruity or malalignment are best treated with internal fixation.

4. Most paediatric fractures are amenable to non-operative treatment, but fractures involving the growth plate require accurate reduction and occasionally internal fixation.

5. Dislocations may be associated with neurovascular injury and require urgent reduction.

6. Trauma is the most common cause of compartment syndrome.

7. Fractures and dislocations can be associated with nerve or vascular injury.

8. Early infection typically occurs in open fractures; the risk is minimized by appropriate early management – wound excision and debridement, skeletal stabilization, and early wound closure or coverage.

9. Non-union affects about 5% of fractures; it is more common in susceptible patients who sustain high-energy or open fractures with extensive damage to the bone blood supply.

10. Mal-union is a relatively common complication after a fracture, especially following non-operative treatment. Some degree of mal-union is relatively well tolerated in some locations, such as the clavicle and humeral shaft.

11. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis is associated with displaced intra-articular fractures; the risk is proportional to the degree of residual joint incongruity.

12. Avascular necrosis is an occasional complication especially in displaced fractures, where the blood supply to one major fragment crosses the plane of the fracture and is disrupted. It is most commonly associated with talar neck, femoral neck and scaphoid fractures.

13. Fat embolism is complication of long-bone fractures and results in symptoms similar to those of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

14. Lower-limb deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) occur in <1% of fractures; risk factors include older age, multiple trauma, lower-limb trauma and concomitant head injury. Low-molecular-weight heparin, unfractionated heparin and foot pumps prevent DVT in patients with fractures.

Definition of fracture

A fracture is any loss in the continuity of bone and is most frequently the result of trauma. The term fracture encompasses all bony injuries, from simple undisplaced cracks in bone to major complex long-bone fractures with extensive soft-tissue injuries. Some additional terms in common use help describe the fracture. An open (compound) fracture is one in which there is a wound in communication with the fracture site. A comminuted fracture is one in which there are more than two main fragments. Inspection of radiographs allows description of the deformity. Angulation describes the relation of the long axis of the proximal and distal segments of bone. Displacement refers to the degree of separation between the bone ends (Fig. 9.1). Rotation is best judged on clinical examination and refers to the degree of rotational malalignment at the fracture site. Angulation, displacement and rotation are described in relation to the major proximal fragment (even if this is quite short).

Principles of treatment

• Reduce the fracture under anaesthesia (if displaced)

• Maintain the reduction until the fracture heals

Reduction is usually desirable in displaced or angulated fractures, but is not always required (e.g. most clavicular fractures heal uneventfully with a satisfactory outcome despite some displacement). The fracture can be reduced by closed methods (e.g. manipulation or traction) or by direct surgical exposure – open reduction. Once the fracture is reduced, the surgeon then has to choose some method of treatment to maintain the reduction until union occurs. Non-operative or operative methods can be chosen. Each method has advantages and disadvantages, and several options can be considered in most situations. The decision is influenced by location and morphology of the fracture, the presence of associated injuries and the experience of the surgeon.

Non-operative treatment

The disadvantages include:

• Reduction is not always precise.

• Stability is often inadequate for major injuries.

• Mal-union rates are higher in adults.

• More outpatient visits and radiographs are required to monitor treatment.

Types of non-operative treatment

1. Bed rest: some fractures can be treated with rest and analgesia alone, e.g. isolated pubic ramus fractures.

2. Cast treatment: reduction and cast application is suitable for many common injuries in adults and children, particularly distal radial fractures.

3. Splints: there is a variety of modern splints available that can be introduced at the outset or during the course of treatment to assist in immobilizing the fracture.

4. Traction: this method of treatment confines the patient to bed, sometimes for long periods, and is seldom used now in adults.

Operative treatment methods

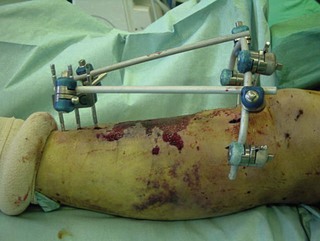

External fixation

External fixation devices are attached to bone by pins or wires and consist of an external frame (Fig. 9.2). Devices vary in design from simple uni-axial frames to complex circular frames for more difficult problems. The main advantages are minimally invasive surgery and versatility of application. Disadvantages are problems with pin-track infection, poor patient acceptance and a higher rate of mal-union. These devices are particularly suitable for use in situations where application of internal fixation would be difficult or risky. Examples include distal metaphyseal fractures, bone where there has been previous osteomyelitis, multiple fractures, or extensive skin damage and swelling following high-energy trauma. External fixation may be used temporarily in these situations until internal fixation is deemed safe.

Indications for external fixation

• Closed fractures with extensive soft-tissue trauma

• Juxta-articular fractures where nailing and plating are technically difficult

• Temporary stabilization of long-bone fractures in multiple trauma

• Leg lengthening after post-traumatic shortening

• Correction of complex post-traumatic angular/rotational deformity.

Internal fixation

Internal fixation devices fall into two main categories: intramedullary devices and plates. Other variations are used, such as screws or wiring techniques. Intramedullary nails are widely used in the treatment of lower-limb long-bone fractures in adults. They can be inserted with minimally invasive surgery and are excellent for restoring normal length, alignment and rotation. They are biomechanically very strong and are ideal for lower-limb diaphyseal fractures, where union times may be prolonged (Fig. 9.3). They are associated with a reliably high rate of union and very low rates of mal-union. Other complications, such as infection, are also very low. They cannot be applied so easily to the bones in the upper limb. The narrow medullary canals in forearm bones make nailing difficult to apply in the radius and ulna. The humerus can be more readily nailed, but the entry points at the elbow and shoulder are associated with complications. In children, flexible intramedullary nails can be used to stabilize long-bone fractures and the radius and ulna. Nails should not cross an open physis in a child.

Plating is most commonly used for metaphyseal fractures, displaced intra-articular fractures and diaphyseal fractures in the upper limb in the adult (Fig. 9.4). The main advantage is that a very precise reduction can be achieved, which is important when anatomical reduction is closely related to functional outcome (e.g. displaced intra-articular fractures). It is a more invasive technique and the complication rate associated with plating of diaphyseal fractures in the lower limb is higher than with intramedullary nailing.

Isolated screws are used in epiphyseal injuries (Salter–Harris types III and IV; see Chapter 11) to maintain continuity of the reduced articular surface and to stabilize a slipped upper femoral epiphysis (see Chapter 25). Percutaneous pinning of unstable fractures that have been reduced by manipulation is a useful and widely used technique in children and is effective when combined with the application of a plaster cast. Examples include percutaneous pinning of a supracondylar humeral fracture and a bayoneted distal radial fracture.

Indications for internal fixation

• Displaced intra-articular fractures – plates, wiring techniques

• Periarticular fractures – plates

• Lower-limb long-bone fractures – intramedullary nails

• Fractures with vascular or nerve injury

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree