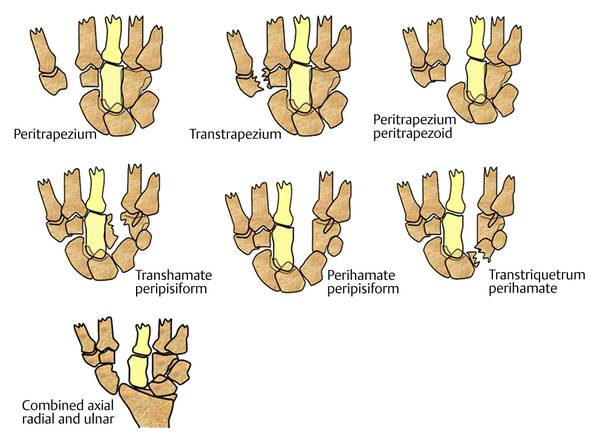

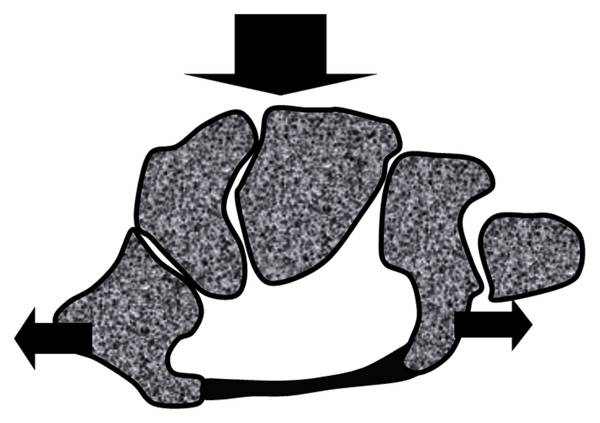

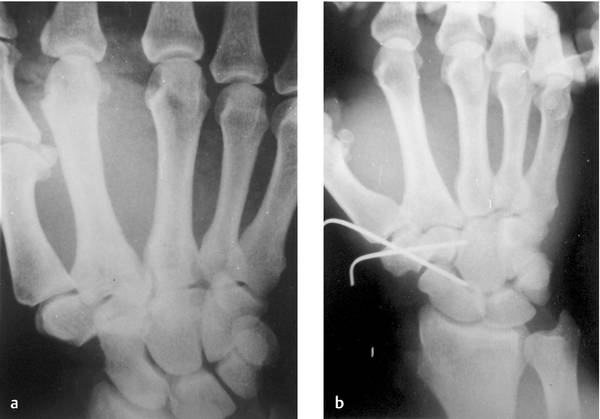

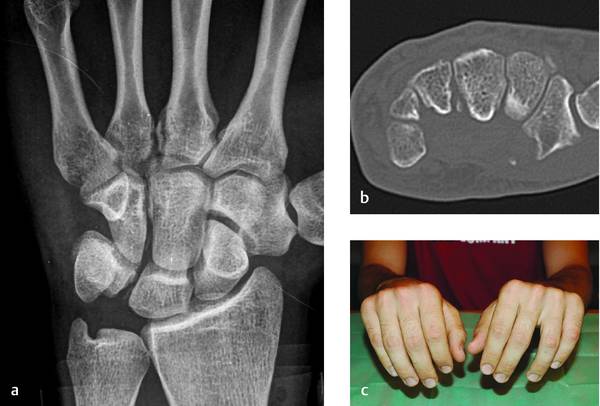

For clarity of treatment we will employ the accepted classification of carpal instabilities into dissociative (CID) affecting relationships between bones of the same row; nondissociative (CIND) affecting relationships between different rows; and complex (CIC) when both these injuries occur together.1 This chapter deals mainly with axial fracture-dislocations and will also pay attention to the isolated bone dislocations and translunate perilunate injuries that have recently received a proposed classification. In 1989 Garcia-Elias et al2 reviewed the literature and clinical reports of the Mayo clinic and proposed a classification for injuries of this type (▶ Fig. 14.1). The mechanism of these injuries is trauma in a dorsopalmar direction over the carpus (▶ Fig. 14.2). This tends to flatten the carpal arcs, both proximal and distal. The line of injury lies between or across the bones of the distal carpal row and through the midcarpal joint. This is why these injuries fall into the category of CIC instabilities described above. Because production of these injuries requires high-energy trauma, there may also be associated lesions such as distal radius fracture3 and, more frequ ently, carpometacarpal (CMC) fracture dislocations or soft tissue damage.4 Fig. 14.1 Garcia-Elias classification. (Reprinted from Garcia-Elias et al. Traumatic axial dislocations of the carpus. J Hand Surg Am. 1989; 14: 446–457 with permission from Elsevier.)2 Fig. 14.2 Representation of the dorsopalmar forces acting on the distal carpal arc that collapses under this pressure. The cases revised by Garcia-Elias et al were classified into six categories: three affecting the radial side of the distal carpal row (peritrapezium, peritrapezium-peritrapezoid, and transtrapezium), and three affecting the ulnar side (transhamate peripisiform, perihamate, and transtriquetrum perihamate). Although both sides can be affected, we could find only one case, reported by Freeland and Rojas in 2001.5 In this case the line of injury ran between hamate and capitate and proximally through scaphoid and lunate, and distally again between scaphoid and capitate and between capitate and trapezoid. Thus, scaphoid, trapezium, and trapezoid maintained their relationship. Lesions affecting the ulnar side between capitate and hamate are the most commonly reported in the literature (58%).6 Among those affecting the radial side—reported to be 40% of axial fracture dislocations—the peritrapezium is by far the most frequent. Nevertheless, some cases of peritrapezium-peritrapezoid have been published although the denomination of the injury does not always follow this classification.7,8,9,10 In the first case,7 a mechanism of transverse compression combined with twisting was reported and Devlies et al9 reported a dorsal blow from the blade in a mixing machine. Both include a transverse compression force such as can be found in rolling presses and other kinds of industrial machinery (▶ Fig. 14.3). Fig. 14.3 An AP radiographic projection of a case of peritrapezium-peritrapezoid dislocation (a). Widening between second and third metacarpal can be seen (b) after reduction; the STT joint lines’ parallelism is restored. In some cases the line of injury may extend beyond the distal carpal row and be prolonged proximally, as in the transtriquetrum perihamate type, or disrupt ligaments between the lunate and the triquetrum (▶ Fig. 14.4). In several case reports, the axial dislocation of the ulnar side (capitate-hamate) progresses proximally through the scapholunate ligaments,11,12,13,14,15,16 which could be considered a variation of axial ulnar fracture-dislocations. Among these there is a particular case reported by Somford et al,15 which had a lunotriquetral coalition. Many of these papers have reported cases as “isolated dislocation of the scaphoid associated with axial carpal dislocation or dissociation,” which is not an exact definition of the injury. “Axial-ulnar fracture dislocation associated with scapholunate dissociation” would be a preferable description. A different mechanism of production (flexion and ulnar deviation) is suggested by Kanaya et al in their case reported in 2010.16 Fig. 14.4 (a) AP X-ray view showing avulsion from the capitate, (b) transverse CT scan view that shows the avulsion of the capitate and also from the trapezium. A dorso palmar compression was the mechanism of the prooduction as stated before. (c) Divergence between ring and long fingers can be observed and flattening of the transversal arch of the head of the metacarpals as a clinical manifestation of the injury. Another possibility affecting the radial side combined with a lunotriquetral injury exists but, to date, only one case has been reported, by Chin and Garcia-Elias.17 Even when this classification is accepted, there are still reported cases that do not conform to it. There is one reported case of dislocation of the whole proximal carpal row.18 These authors speculate on a mechanism of pure extension and axial load without ulnar or radial inclination. There is another group of cases that could be considered a different type and that instead of axial fracture-dislocations might be named transverse fracture-dislocations of the carpus. Three reports have been published and reported as transscaphoid, transcapitate, and transhamate axial dislocation.19,20,21 Two have been published under the same denomination and the other as pericapitate rather than transcapitate.19,20 The qualification of “axial” needs to be defined as the line of injury being completely transversal, lying in the coronal plane. Diagnosis of these injuries is not always easy. Concomitant lesions and nonideal radiological projections make it difficult and some cases are not diagnosed even after first-case surgery, as in the case illustrated in ▶ Fig. 14.5. Radiological references such as Gilula lines and loss of parallelism of joint surfaces are of value in identifying something wrong in the carpus.6 CT scanning is of great value for clearly defining the type of injury and revealing occult injuries. Fig. 14.5 A case of perihamate axial dislocation associated with a transhamate CMC dislocation. (a) Initial radiograph that shows an associated fracture of the neck of the fifth metacarpal and of the bases of the third and fourth metacarpals but no suspicion of injury to the capitate–hamate joint. (b) After initial treatment, widening of the space between hamate and capitate can be seen. Also transhamate fracture dislocations of the third, fourth, and fifth CMC joints were present. (c) After fixation for arthrodesis of the CMC of the third and fourth metacarpals, reduction of the dislocation of the fifth metacarpal and fixation of the dorsal fragment of the hamate and arthrodesis between hamate and capitate. (d) After removing the hardware and making a tenolysis of the extensor tendon of the small finger.

14.2 Axial Fracture-dislocations of the Carpus

14.2.1 Garcia-Elias et al classification

14.2.2 Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree