Forearm Osteotomy for Multiple Hereditary Exostoses

Carley Vuillermin

Carla Baldrighi

Scott N. Oishi

DEFINITION

ANATOMY

Knowledge of the normal anatomy and biomechanics of the forearm in the immature individual is instrumental in understanding the pathogenesis of the deformity and ultimately in planning appropriate treatment.

During forearm pronation-supination, the relationship between the radius and ulna changes. This rotational movement requires near-anatomic alignment of both as well as integrity of the proximal and distal radioulnar joints and the interosseous membrane. Minimal axial or rotational bone deformity, asymmetric bone shortening, or ligament instability can hinder this function.

The ulna acts like a swivel hinge around which the radius rotates. The axis of forearm rotation is oblique.

PATHOGENESIS

Approximately 10% of individuals with manifestations of multiple exostoses have no family history of MHE.22

The prevalence of MHE in the general population is estimated to be at least one in 50,000, with a median age of first diagnosis of 2 to 3 years of age (exostoses rarely develop before age 2 years).22 An average of five or six exostoses, involving both upper and lower extremities, is found at the time of the first consultation.9

The presence of exostoses is almost always evident by the age of 12 years.

Osteochondromas develop at numerous sites in the immature skeleton, they may affect any bone except the skull. They most commonly affect the ends of long bones and flat bones including the scapula and pelvis.

Osteochondromas consist of a base or stalk covered by a cartilaginous cap. They arise from the peripheral aspect of the growth plate of bones that undergo endochondral ossification.14

They are the product of abnormal proliferation of chondroblasts and subsequent defective remodeling of the metaphysis. This leads to the two main characteristics of this condition: skeletal metaphyseal exostoses and retardation of longitudinal bone growth.

They migrate away from the physis with longitudinal growth.14

In MHE, the exostoses vary greatly in number, location, size, and configuration. They tend to have a more irregular and bizarre shape than solitary osteochondromas.

Should always be continuous with the medullary cavity of the bone from which they arise

Once skeletal maturity is reached, the lesions will become quiescent.22 Lesions that enlarge after skeletal maturity should be investigated to exclude malignant change.

NATURAL HISTORY

Deformity of the forearm is seen in 30% to 60% of the individuals with MHE.22 The forearm deformities can be progressive and result in a variable amount of weakness, pain,4 functional limitation, and aesthetic deformity.

The deformities are almost always accompanied by discrepancy in length between the two bones. Asynchronous longitudinal growth between paired bones leads to a greater risk of anatomic distortion. Most of the longitudinal growth of the ulna occurs at the distal physis,15 which is also the more commonly affected physis (30% to 85% of the cases).22, 23

The affected ulna typically remains relatively shortened and curved, and this often leads to significant bowing of the radius. When the ulna is shorter, the ulnar-sided soft tissue acts as a tether, causing bowing of the radius. In addition, the local presence of the exostosis itself causes radial bowing by disturbing hemiepiphy-seal growth.15

A serious risk associated with MHE is the potential for malignant transformation of an exostosis into chondrosarcoma. This can occur at any age, but it is exceedingly rare during childhood.22

Patients affected by MHE have a normal life expectancy unless malignant degeneration and metastasis develop.9 The risk of malignant degeneration in adults with MHE has been reported to range from 0.57% to 5%.12, 22, 31

MHE can have a serious influence on the quality of life of affected individuals, affecting sporting participation, occupation, and daily activities.8

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The diagnosis is rarely difficult as 90% of affected individuals have a positive family history, and therefore initial history taking should focus on the symptoms and functional impairment that exist.

Physical examination of the upper extremity should assess for location of disease burden and common associated findings.

It is a common finding that the deformity is quite asymmetric. One forearm may be heavily affected, whereas the other relatively spared.

Shortening of the forearm, specifically relative shortening of the ulna, increased radial bow and possible radial head dislocation.

A mild flexion deformity of the elbow is often present.

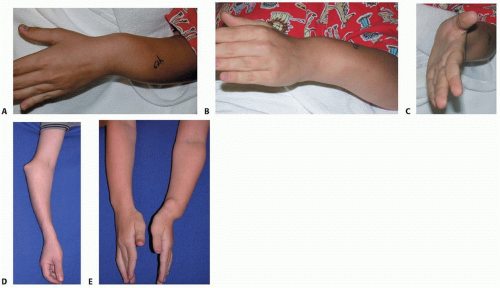

At the wrist level, an increased ulnar tilt of the radial epiphysis, ulnar deviation of the hand, and progressive ulnar translocation of the carpus are often present. These deformities can lead to a loss of radial deviation of the hand and loss of pronation-supination of the forearm (FIG 1).

The loss of forearm pronation-supination may develop early and become progressively more severe as the child ages.26 Pronation-supination may be limited due to altered mechanical alignment, osteochondroma blocking motion, or radial head dislocation. The greater the number of osteochondromas and shorter the ulna, the greater the loss of motion.10, 32

Radial head dislocation is reported to occur in 22% of the affected forearms.23 It may present as pain, a mass on the lateral side of the elbow, altered carrying angle, decreased elbow range of motion or decreased pronation-supination, or catching.

It is possible to have neurologic impingement from either direct compression by an osteochondroma or through deformity including radial head dislocation.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographic evaluation is usually sufficient to confirm the diagnosis and to determine the number, location, and morphology of the exostoses (FIG 2).

Like solitary osteochondromas, the exostoses may be described as sessile or pedunculated; they nearly always point away from the physis, however in the hand they may not. In MHE, the lesions tend to be larger and have a more bizarre shape (see FIG 2).

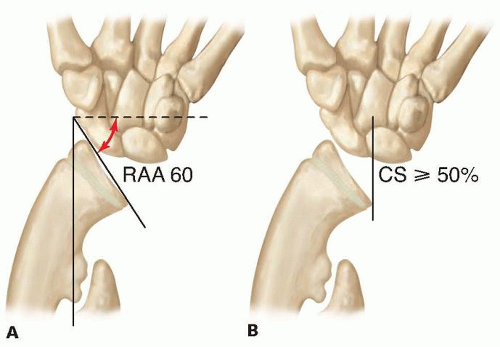

At least two full views of the forearm (true anteroposterior and lateral containing both the elbow and the wrist) are necessary to properly assess the ulnar variance, the radial articular angle (RAA), the carpal slip, and the relative radial bow. These radiographic measurements are useful in the surgical planning phase (FIG 3).2

FIG 3 • The RAA and carpal slip (CS). A. The RAA is defined as the angle between a line running along the articular surface of the radius and another line that is perpendicular to a line joining the center of the radial head to the radial border of the distal radial epiphysis (the radial styloid in skeletally mature individuals). The normal range of the angle is 15 to 30 degrees. B. CS is measured by determining the percentage of the lunate that is in contact with the radius. First, a line is drawn from the center of the olecranon through the ulnar border of the radial epiphysis (the radial articular surface in skeletally mature individuals).1 This line normally bisects the lunate. An abnormal CS is defined as being present when ulnar displacement of the lunate exceeds 50%. (Adapted from Akita S, Mursae T, Yonenobu K, et al. Long-term results of surgery for forearm deformities in patients with multiple cartilaginous exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:1993-1999.)

Alterations of the radial head on radiographs must always be assessed. They range from flattening to subluxation and complete radial head dislocation.

Masada et al15 morphologically classified the involvement of the forearm in MHE into three types (FIG 4). This classification is also used for treatment planning.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree