Forearm Fractures: Intramedullary Nailing

Daniel M. Zinar

Indications/Contraindications

Diaphyseal fractures of the forearm in adults are relatively common injuries that usually occur after intermediate or high-energy trauma. With widespread dissemination of the methods of fixation advocated by the AO/ASIF, plate fixation of these injuries has become the gold standard. Numerous authors have shown high rates of union and excellent functional outcomes after plate osteosynthesis of these fractures. The chief drawbacks with this fixation method are the long incisions and wide exposure necessary to reduce and fix the fractures. Radial nerve palsies are common after open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and refracture rates of the forearm vary from 1% to 20% and are most common in the proximal one third. Furthermore, the resultant scar can be a significant cosmetic deformity, particularly in female patients.

Intramedullary nailing of forearm fractures is not meant to replace conventional plate fixation. Rather, it is indicated in a small subgroup of patients in whom nailing may be more advantageous than plate osteosynthesis. The indications for intramedullary nailing of the radius and ulna include segmental fractures, gunshot fractures with severe comminution, refracture of the forearm after plate removal, fracture occurring above or below an existing plate, unstable fractures in children or adolescents, and fractures in athletes who participate in contact sports.

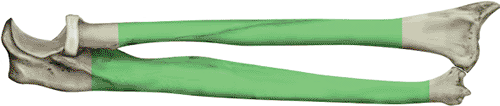

Forearm nailing is contraindicated in adults whose intramedullary canal measures less than 3 mm at the narrowest point. Fractures less than 3 cm from the proximal or distal end of the bone should not be nailed because of inadequate fixation of the short segment of bone (Fig. 11.1). Nailing should be avoided in patients with preexisting deformity of the forearm that would preclude nailing without an osteotomy. Finally, nailing is not the fixation method of first choice to stabilize corrective osteotomies or treat nonunions.

Preoperative Planning

Forearm fractures may occur as an isolated injury or after multiple trauma. In the severely injured patient, basic and advanced trauma life support (ATLS) and a full trauma evaluation and resuscitation are mandatory. Once life-threatening and limb-threatening injuries have been addressed, the injured arm is carefully evaluated. The entire upper extremity is inspected for open wounds, ecchymosis, abrasion, deformity, and other injury. The limb is palpated from shoulder to fingers by the surgeon looking for areas of tenderness or fracture crepitus. Ipsilateral injuries to the shoulder, upper arm, elbow, wrist, and hand commonly occur after high-energy trauma. The arm is critically examined to ensure that a compartment syndrome does not exist. If the surgeon has any doubt, the compartment pressure should be measured. After the lower leg, the forearm is the second most common site for a compartment syndrome. The axillary, brachial, radial, and ulnar pulses should be palpated and compared with those of the opposite side. The sensory and motor components of the radial, medial, and ulnar nerves must be documented. In patients with proximal injuries, the function of the brachial plexus requires evaluation. If the fracture is open, the wounds should be sterilely dressed, the limb splinted, and intravenous antibiotics administered. The patient should be brought to the operating room as soon as possible for irrigation and debridement.

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the entire injured and uninjured forearm are obtained to determine proper nail length, diameter, and radial bow. Three methods of determining correct nail length are used: First, the patient’s uninjured arm is measured with a tape measure from the tip of the olecranon to the ulnar styloid, and 1 cm is subtracted from the measurement; second, a nail of known length is intraoperatively placed against the affected bone while traction is used to keep the bone to the appropriate length, and the fit of the nail is checked fluoroscopically; or third, the fit is checked preoperatively through the use of radiographic templates with known magnification parameters. Because the radial head is often difficult to palpate, the radial length can be determined by subtracting 2 cm from the ulnar length.

Special projections, such as oblique radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scanning, or other imaging modalities, are not helpful in preoperative planning.

Surgery

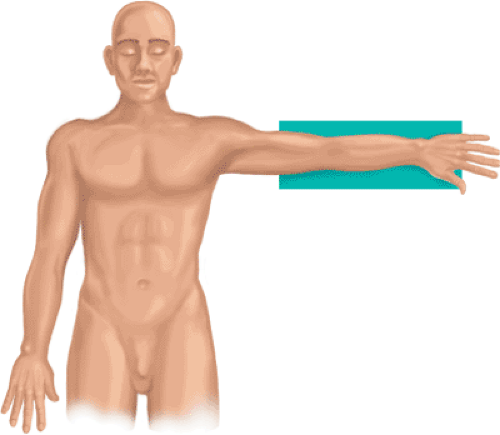

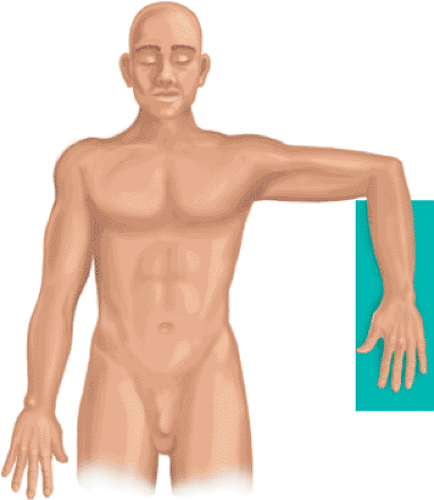

General anesthesia is preferred over regional anesthesia because the relaxation obtained improves the chances of achieving a closed reduction. Closed nailing is more successful if surgery is done within 72 hours of injury. The patient is placed supine on an operating table, and a radiolucent arm table is used to support the extremity (Fig. 11.2). A mobile, C-arm, image intensifier is brought in from the head of the table. The surgeon sits at the axilla while the assistant is positioned at the end of the hand table. For ulnar nailing, the shoulder is abducted and internally rotated, and the elbow is flexed to 90 degrees. The elbow is “bumped” with a stack of towels for easier access to the olecranon (Fig. 11.3).

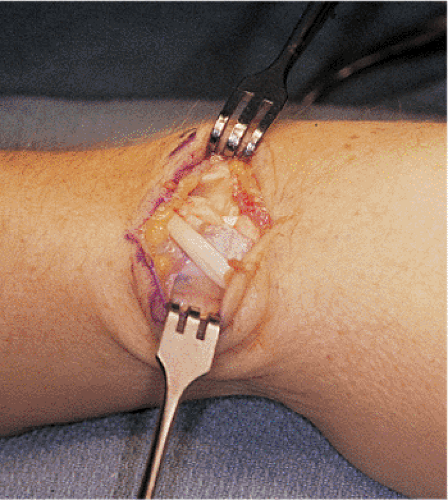

Fracture reduction can be accomplished by a closed or open method. Closed nailing is preferable because it preserves blood supply and enhances fracture healing. Closed reduction is achieved by longitudinal traction or direct pressure at the fracture site. Traction

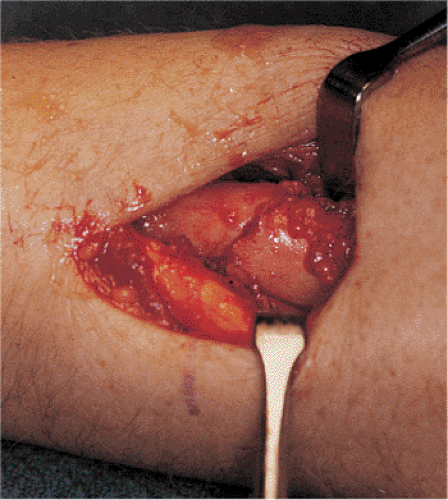

devices with finger traps have not been successful. The surgical assistant should wear sterile lead gloves to minimize radiation exposure to his/her hands. When the fracture fragments are locked in bayonet apposition, a mini–open technique through a 2- to 4-cm incision may be used to reduce the fragments (Fig. 11.4).

devices with finger traps have not been successful. The surgical assistant should wear sterile lead gloves to minimize radiation exposure to his/her hands. When the fracture fragments are locked in bayonet apposition, a mini–open technique through a 2- to 4-cm incision may be used to reduce the fragments (Fig. 11.4).

Figure 11.3. With nailing of the ulna, the elbow is bent 90 degrees for access to olecranon, where the surgeon will place the entry portal. A stack of towels is placed under the elbow. |

Entry Portal

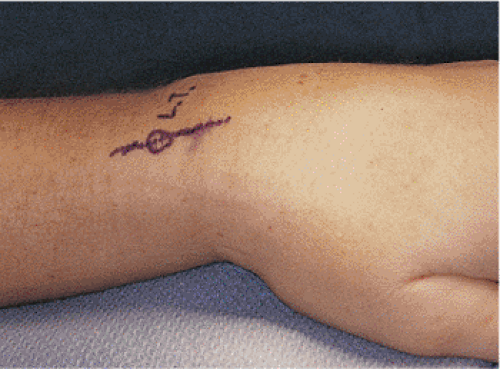

A tourniquet is used whenever possible to minimize blood loss. If both bones are fractured, the radius is approached first. However, both bones are prepared for nailing before nailing is initiated in either bone. A 1.5-cm incision is made just lateral to Lister’s tubercle at the distal radius (Fig. 11.5). The extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon is identified and

released from its sheath around Lister’s tubercle (Fig. 11.6). The interval between the short and long wrist extensors is identified (Fig. 11.7). The surgeon must identify the distal edge of the radius to avoid inadvertent insertion through the scaphoid. The medullary canal is entered obliquely through a 2.0-mm pilot drill hole at the dorsal margin of the radius (Fig. 11.8). The wrist is flexed and placed over a stack of towels to prevent inadvertent perforation of the volar cortex (Fig. 11.9). The entry portal is enlarged with a cannulated 6.0-mm reamer (Fig. 11.10).

released from its sheath around Lister’s tubercle (Fig. 11.6). The interval between the short and long wrist extensors is identified (Fig. 11.7). The surgeon must identify the distal edge of the radius to avoid inadvertent insertion through the scaphoid. The medullary canal is entered obliquely through a 2.0-mm pilot drill hole at the dorsal margin of the radius (Fig. 11.8). The wrist is flexed and placed over a stack of towels to prevent inadvertent perforation of the volar cortex (Fig. 11.9). The entry portal is enlarged with a cannulated 6.0-mm reamer (Fig. 11.10).

Figure 11.4. A 4-cm mini–open incision is used to reduce a completely displaced fracture of the radius. |

Figure 11.5. A 2-cm incision is centered over Lister’s tubercle for creation of an entry portal into the radius. |

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|