The dancer’s foot and ankle are subjected to high forces and unusual stresses in training and performance. Injuries are common in dancers, and the foot and ankle are particularly vulnerable. Ankle sprains, ankle impingement syndromes, flexor hallucis longus tendonitis, cuboid subluxation, stress fractures, midfoot injuries, heel pain, and first metatarsophalangeal joint problems including hallux valgus, hallux rigidus, and sesamoid injuries will be reviewed. This article will discuss these common foot and ankle problems in dancers and give typical clinical presentation and diagnostic and treatment recommendations.

Key points

- •

The dancer’s foot and ankle are subjected to high forces and unusual stresses in training and performance.

- •

To keep dancers healthy, the health care team and the dancer must work together.

- •

The physician must be an advocate for the dancer and work to provide an accurate diagnosis and an effective treatment strategy.

- •

Monitoring performance and rehearsal load, fitness, and general health of the dancer will help to maximize the dancer’s healing potential.

- •

Creativity is needed to modify treatment plans to accommodate the dancer’s need to maintain strength, flexibility, and fitness during recovery.

Introduction

Dance is a demanding art form requiring years of training, musicality, and motor control, often at the extremes of joint range of motion. Elite dancers are athletes whose rigorous training, rehearsal and performance schedules predispose them to injury. The stresses of dance can result in common overuse injuries as well as some injuries unique to dancers. Dance has many forms, including classical ballet, modern, contemporary, jazz, tap, break dance, hip-hop, musical theater, ballroom, Irish, African, Flamenco, folk, aerial and contact improvisation.

Reports on professional dancers show high rates of injury in ballet, modern, and Irish dancers. In a Swedish study, 95% of the professional dancers sustained at least 1 injury during a 1-year study period. The foot and ankle are the most frequently injured areas in dancers, with significantly higher rates reported in female ballet dancers. The sur les pointes position requires maximal ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot plantar flexion, while placing high forces across those joints ( Fig. 1 ). Dance injuries may be the result of acute trauma, such as landing from a leap or turn, or more commonly from repetitive microtrauma, usually after a rapid increase in training volume and intensity. Menstrual irregularities, disordered eating, low energy availability, low vitamin D, and osteopenia may contribute to dancers’ risk for injury or delayed healing.

This article will review some common problems involving the foot and ankle in dancers, precipitating factors, clinical presentation, diagnostic tips, and treatment recommendations.

Introduction

Dance is a demanding art form requiring years of training, musicality, and motor control, often at the extremes of joint range of motion. Elite dancers are athletes whose rigorous training, rehearsal and performance schedules predispose them to injury. The stresses of dance can result in common overuse injuries as well as some injuries unique to dancers. Dance has many forms, including classical ballet, modern, contemporary, jazz, tap, break dance, hip-hop, musical theater, ballroom, Irish, African, Flamenco, folk, aerial and contact improvisation.

Reports on professional dancers show high rates of injury in ballet, modern, and Irish dancers. In a Swedish study, 95% of the professional dancers sustained at least 1 injury during a 1-year study period. The foot and ankle are the most frequently injured areas in dancers, with significantly higher rates reported in female ballet dancers. The sur les pointes position requires maximal ankle, hindfoot, and midfoot plantar flexion, while placing high forces across those joints ( Fig. 1 ). Dance injuries may be the result of acute trauma, such as landing from a leap or turn, or more commonly from repetitive microtrauma, usually after a rapid increase in training volume and intensity. Menstrual irregularities, disordered eating, low energy availability, low vitamin D, and osteopenia may contribute to dancers’ risk for injury or delayed healing.

This article will review some common problems involving the foot and ankle in dancers, precipitating factors, clinical presentation, diagnostic tips, and treatment recommendations.

Ankle sprains

Ankle inversion injury is the most common traumatic injury in dance as it is in athletics. Many authors report ankle sprains as the most frequent acute injury. The mechanism of injury is typically an inversion injury (rolling over the lateral border of the foot), often while en pointe or demi-pointe, or in a missed landing from a jump. The lateral ligaments are most frequently injured, with the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) the most commonly injured ligament. The ATFL is injured when the ankle is plantar flexed; the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) is injured when the ankle (foot) is in dorsiflexion (neutral) and inverted.

A history of previous ankle sprain is the greatest risk factor for an ankle sprain injury. Dancers and athletes who have had an ankle sprain have impaired dynamic postural control (more postural sway than controls or uninjured dancers). Even after return to full professional dance or sport participation, and without complaints of instability, measurable differences in postural sway can be demonstrated.

Diagnosis includes physical examination revealing tenderness to palpation over the anterolateral ankle ligaments, swelling, and ecchymosis. Radiographs should be obtained if there is any bony tenderness over fibula, sinus tarsi, or fifth metatarsal. If symptoms do not improve in a week, a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan should be obtained to identify possible osteochondral injury to the talus or occult fracture.

Most sprains resolve with conservative management. Early functional treatment of ankle sprains is recommended for dancers. Compression bandage, icing, ankle air-stirrup brace in athletic shoes outside of class, and limited class participation should be instituted as pain allows. Severe sprains may require use of a removable boot for 3 weeks. The boot should be worn for walking and sleeping, but removed for icing and range-of-motion exercises. Dancers with high-level sprains may need to do floor barre classes, Pilates or Gyrotonics before return to class and performance.

Note that dancers with generalized hypermobility may have a prolonged recovery compared with non-hypermobile dancers.

Rehabilitation should include strengthening, edema control, and range of motion and proprioception exercises. Ballet dancers require full mobility of their hindfoot and midfoot joints to dance en pointe. An ankle sprain can lead to posterior ankle impingement if adequate care to achieve posterior talar glide and ankle dorsiflexion is not obtained, as the insufficient ATFL ligament allows the talus to move forward in the plantar flexed position, resulting in impingement of bone and/or soft tissues in the posterior ankle joint. It is important in dancers to encourage work on attaining full dorsiflexion at the tibiotalar joint following an ankle sprain; therapists should be encouraged to assist the dancer in posterior talar glide with manual therapy. Many dancers have a very flexible ankle with a moderately or highly arched (cavus) foot. They may have subtle hindfoot varus and are more prone to reinjury. One study found that fatigue-induced changes of dynamic postural control were more pronounced in those athletes with a history of ankle sprain, while changes in static sway velocity were similar for both groups. Therefore, despite successful return to full dance after an ankle sprain, some sensorimotor control deficits remain, which can put the dancer at risk for reinjury of the ankle. Work on the entire kinetic chain is crucial for full recovery. Core strengthening, proprioception, and proximal hip strengthening exercises should be included in any dancer’s rehabilitation from ankle sprain in addition to fibularis longus and brevis muscle strengthening. Work on unstable surfaces and balance tasks with eyes closed will help in assisting return of proprioception and full function. Practicing relevés in parallel position with a tennis ball held between the malleoli can help the injured dancer retrain ankle strength and motion in a neutral ankle position.

Achilles

Chronic Achilles tendinopathy, retrocalcaneal bursitis, and acute tendinitis may be seen in male and female dancers. Comin and colleagues evaluated Achilles and patellar tendons in 79 professional ballet dancers and found a 12% prevalence of sonographic abnormalities in the Achilles and patellar tendons of asymptomatic dancers. Dancers who force their turnout, leading to increased pronation in the midfoot and hindfoot, are at risk for Achilles tendon problems. Failure of the dancer to land with his or her heels on the ground from jumps also can contribute to shortening of the Achilles tendon and risk for injury. In young dancers during periods of rapid growth, there is relative tightness and weakness of the gastrocnemius–soleus complex, placing them at risk for Achilles tendinitis. In a prospective study, Mahieu and colleagues identified plantar flexion weakness and increased dorsiflexion excursion as significant predictors for Achilles tendon overuse injury. In the Comin study, only those dancers with hypoechoic changes seen on ultrasound later developed symptomatic Achilles tendinitis, suggesting that ultrasound in asymptomatic dancers may help identify those at risk.

Tight ribbons around the ankle in ballet dancers may cause irritation. Ballet dancers may need adjustment of tight ribbons around the ankle, or the use of ribbons with elastic sewn in the area over the tendon to reduce pain. Careful stretching and the use of a night splint while sleeping can alleviate most symptoms. Eccentric strengthening exercises, physical therapy with modalities such as Graston technique, or deep tissue massage may be beneficial. The use of a stretch box in the studio and back stage at the theater has been found to be a good preventative measure for some companies.

Achilles Tendon Rupture

Rupture of the Achilles tendon is unusual in female dancers, more commonly seen in male dancers over age 30. It typically presents as a sharp pain and inability to rise up on the toes to demi-pointe. Landing in hyperdorsiflexion or eccentric loading of the foot during push-off can result in an acute Achilles tendon rupture. Thompson test will be positive, and when examining the patient in the prone position with the knees flexed, the relaxed resting posture of the injured leg will demonstrate the foot in more dorsiflexion than the uninjured side. A palpable defect is usually present, but acute swelling may mask this finding.

Acute ruptures in dancers generally are treated with surgical repair, and any suspected rupture should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon.

Sever disease

Sever disease (calcaneal apophysitis) is a common cause of posterior and or plantar heel pain in young dancers with open growth plates. There is a high incidence in Irish dancers, but it can also be seen in any child or adolescent dancer who complains of heel pain. The dancer may complain of morning pain or pain with jumping, heel strike, and percussive movements. Radiographs usually are negative but may show relative widening of growth plate. On physical examination, the dancer will be tender over the apophyseal ossification center and calcaneal growth plate.

Treatment includes avoidance of painful activities, usually 3 weeks in removable boot cast, night splint for sleeping, and gentle Achilles stretches. The young dancer may need to continue the night splint for an additional month as symptoms subside. Return to dance includes relative rest such as avoidance of jumps and other painful activities until symptoms are resolved.

Plantar fascial strain

The plantar aponeurosis is a strong band of fascia extending from the base of the heel to the base of the toes. The plantar fascia may be strained, partially torn, or simply inflamed (plantar fasciitis). Occasionally there is an acute injury, most often insidious in onset after increased training intensity. Walls and colleagues reported on MRI findings of the right ankles in 18 professional Irish dancers; insertional Achilles tendonopathy was observed in 14 dancers, and plantar fasciitis was seen in 7 dancers.

Dancers will usually have pain with their first few steps in the morning, may have tenderness over the plantar fascia, and rarely will have ecchymosis or swelling. Diagnosis is based on physical examination with tenderness over the palpation along the plantar fascia worse with dorsiflexion of the toes and decreased with plantar flexion of the toes. Calcaneal wall tenderness if present should alert the clinician to a possible calcaneal stress fracture (or Sever disease in a skeletally immature dancer) and need for further imaging.

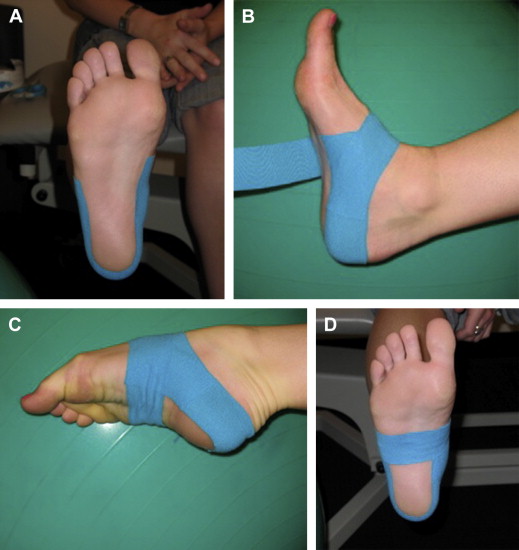

Treatment should include relative rest, including avoiding painful activities, icing, calf stretches and plantar arch stretches, stiff soled shoes when not dancing (such as clogs or hiking boots), and use of a dorsiflexion night splint for sleeping. In severe cases, a removable boot for walking for 3 to 6 weeks may be required. Many dancers get relief from taping the arch for dance until symptoms improve ( Fig. 2 ).

Ankle impingement syndromes

Posterior Ankle Impingement

Posterior ankle impingement is a painful condition due to compression of the soft tissues between the posterior edge of the tibia and the calcaneus when the ankle is in plantar flexion. Bony impingement may be associated with an accessory bone of the ankle, called an os trigonum, or a prominent posterior lateral process of the talus called Steida process ( Fig. 3 ). Some authors have reported concurrent flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tenosynovitis secondary to an impinging os trigonum in dancers. A fracture of the posterolateral process of the talus can also cause posterior ankle pain.

Dancers with posterior ankle impingement usually complain of recurrent pain posterior and lateral, behind the fibularis tendons and stiffness and limitation in plantar flexion. Pain is exacerbated by plantar flexing the foot and relevé. This condition may be mistaken for fibularis or Achilles tendonitis, and may follow an ankle sprain. Those with FHL tendonitis and os trigonum have posteromedial ankle tenderness and pain with flexion of the great toe against resistance. Crepitus may be palpated behind the medial malleolus with range of motion of the great toe. Triggering of the great toe may be present. Functional hallux rigidus may be present, as demonstrated by a limitation of great toe dorsiflexion with the knee fully extended and the ankle in full dorsiflexion.

The dancer complains of decreased active and passive plantar flexion, and may have difficulty achieving the full pointe position on the affected side. Swelling and tenderness may be present behind the lateral ankle joint anterior to the Achilles tendon. It is often exacerbated by forcing plantar flexion on the affected side to achieve as much range of motion as the unaffected side. Dancers with posterior ankle impingement will have a positive plantar flexion sign: pain with forced passive plantar flexion performed by the practitioner with the dancer’s knee flexed at 90°. This test will not be positive in Achilles, fibularis, or isolated FHL tendinitis.

Radiographs in maximal plantar flexion, or with the dancer en pointe, can demonstrate a bony block or os trigonum ( Fig. 4 A). MRI is helpful to identify posterior bone edema in the talus and calcaneus, and to identify fluid in the FHL tendon sheath. An injection of lidocaine posterior to the fibularis tendons with pain relief can be diagnostic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree