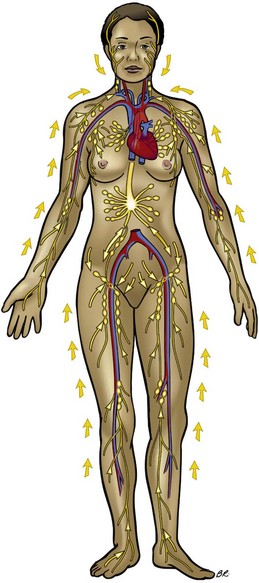

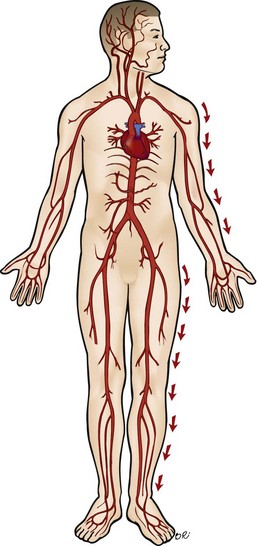

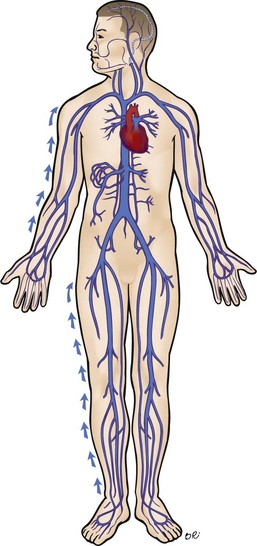

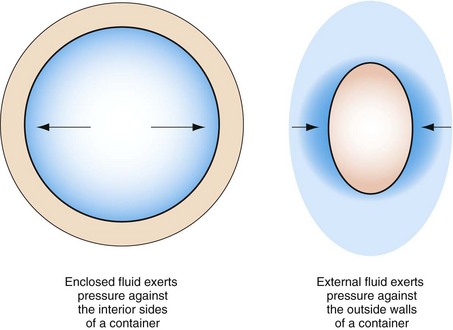

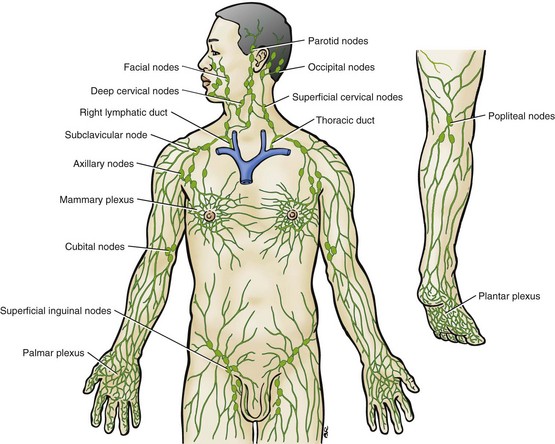

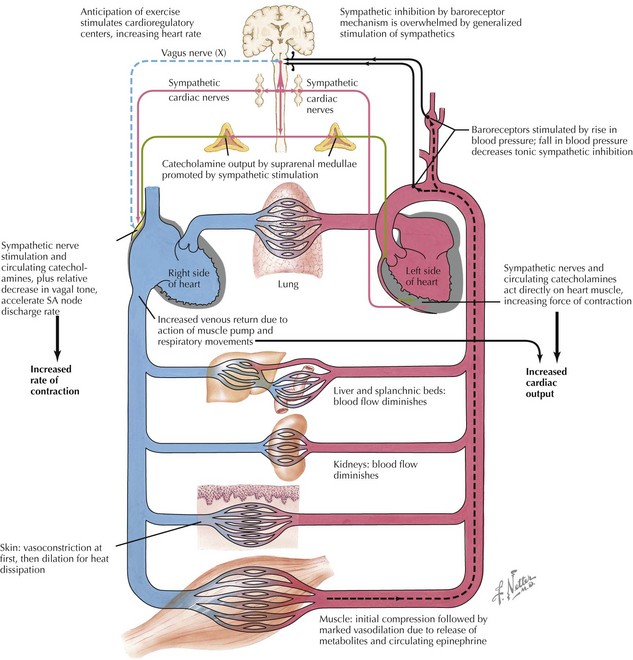

Chapter 13 Indirect and Direct Functional Techniques Step-by-Step Protocol for Full-Body Lymphatic Drain Step-by-Step Protocol for Lymphatic Drain Massage for Swelling of an Individual Joint Area or Contusion Multifidi, Rotatores, Intertransversarii, and Interspinalis Subscapularis and Latissimus Dorsi Rhomboid, Pectoralis Major and Minor, Anterior Serratus Sacroiliac Joint and Pelvis Alignment After completing this chapter, the student will be able to perform the following: 1 Perform indirect functional techniques. 2 Perform direct functional techniques. 3 Perform circulation support and lymphatic drain massage. 4 Perform connective tissue application. 5 Perform trigger point therapy. A sequence of indirect and direct functional techniques is shown in Figure 13-1. FIGURE 13-1 Examples of direct and indirect application. A, Moving tissues into ease takes less effort. B, Moving tissues into bind requires more effort. C, The indirect ease position places target tissues on slack. D, Moving tissue with direct methods to and through bind makes tissues taut. E, Local tissues can be addressed by moving them into ease and holding. F, Direct/bind local tissue stretching is effective. G, Very specific points can be addressed first by moving the area into ease. H, Then, after holding a specific target area in ease, move the area into bind, possibly just into the bind. 1. The blood circulatory system, including arteries and veins 2. The interstitial or anatomic space around cells and lymphatic vessels • Lack of exercise. Exercise in which muscles alternately contract and relax stimulates lymph circulation and cleans muscle tissue. If muscles stay contracted or flaccid, lymph circulation decreases drastically inside muscles, and edema can result. • Overexercise. During exercise, both blood pressure and capillary permeability increase, allowing more fluid to seep into interstitial spaces. If movement of fluid exceeds the ability of the lymphatic capillaries to drain the areas, fluid accumulates. This seems to be a contributing factor to delayed-onset muscle soreness. • Salt. The body maintains a specific ratio of salt to fluids. The more salt a person consumes, the more water is retained to balance it, which can result in edema. • Heart and kidney disease. These diseases affect blood and lymph circulation. Lymph massage stimulates the circulation of lymph. Caution is indicated because the increase in fluid volume could possibly overload an already weakened heart and kidneys. • Menstrual cycle. Water retention and a swollen abdomen are common before or during the menstrual cycle. • Lymphedema. Lymphedema is a condition of stasis of lymph secondary to obstruction of lymph vessels or disorders of the lymph nodes. Limbs affected by this condition become very swollen and painful, resulting in difficulty moving the affected limb and disfigurement. Lymphedema can be life-threatening. Interstitial fluid is contaminated, and even small wounds can become infected. • Inflammation. Increased blood flow to an injured area and release of vasodilators, which are part of the inflammatory response, can cause edema in localized areas. This is a common response to injury and surgery. • Other causes. Medications, including steroids, hormones, and chemotherapy for cancer, may cause edema as a side effect. Scar tissue and muscle tension can cause obstructive edema by restricting lymph vessels. Lymph circulation involves two steps: 1. Interstitial fluid flows into the lymphatic capillaries. Plasma is forced out of blood capillaries into spaces around the cell walls. As fluid pressure between cells increases, cells move apart, pulling on the microfilaments that connect the endothelial cells of the lymph capillaries to tissue cells. This pull on the microfilaments causes the lymph capillaries to open like flaps, allowing tissue fluid to enter the lymph capillaries. 2. Lymph moves through a network of contractile lymphatic vessels. The lymphatic system does not have a central pump, as the heart does. Various factors assist in the transport of lymph through the lymph vessels. The massage application consists of a combination of short, light, pumping, gliding strokes beginning close to the torso at the node cluster and those directed toward the torso; the strokes methodically move distally. The phase of applying pressure and drag must be longer than the phase of release. The releasing phase cannot be too short because the lymph needs to drain from the distal segment. Therefore, the optimal duration of the pressure and drag phase is 6 to 7 seconds; for the release phase, it is about 5 seconds. This pattern is followed by long, surface gliding strokes with a bit more pressure to influence deeper lymph vessels. The direction is toward the drainage points (following the arrows on the diagram in Figure 13-2). When possible, position the area being massaged above the heart, so that gravity can assist lymph flow. (See specific protocol, beginning on page 219.) The purpose of circulatory massage is to stimulate efficient flow of blood through the body. Current research seems to indicate that this effect is not as pronounced as was once believed (see Chapter 3). However, because the research findings are somewhat mixed, it is prudent to consider a form of massage application that logically would support this body function by mimicking normal function. Compression is applied over the main arteries, beginning close to the heart (proximal), and systematically moves distally to the tips of the fingers or toes. Manipulations are applied over the arteries, with a pumping action at a rhythm of approximately 60 beats per minute, or whatever the client’s resting heart rate is. Compressive force changes internal pressure in the arteries, stimulates intrinsic contraction of arteries, and encourages movement of blood out to the distal areas of the body. Compression also begins to empty venous vessels and forms an arterial-venous pressure gradient, encouraging arterial blood flow (Figure 13-3). The next step is to assist venous return flow. This process is similar to lymphatic massage in that a combination of short and long gliding strokes is used in conjunction with movement. The difference is that lymphatic massage is done over the entire body, and movements are usually passive. With venous return flow, gliding strokes move distal to proximal (from fingers and toes to the heart) over the major veins. The gliding stroke is short—about 3 inches. This enables the blood to move from valve to valve. Long gliding strokes carry blood through the entire vein. Both passive and active joint movements encourage venous circulation. Placing the limb or other area above the heart brings gravity into assistance (Figure 13-4). Chronic swelling usually occurs around joints, tendons, and bursae. Edema acts as a protective mechanism in attempting to reduce the problem that is causing the inflammation. A portion of the treatment for this condition involves addressing fluid issues of both blood and lymph. When massage is used, the goal is to reduce the fluid enough to increase function—not to interfere with the protective process and increased stability provided by hydrostatic pressure (Figure 13-5). Permeability is the rate at which a fluid (water) moves across a membrane. Fluid moves by osmosis and diffusion. The application of effective massage is dependent on all of these factors (Figure 13-6). FIGURE 13-6 Effects of exercise on circulation. (Netter illustration from www.netterimages.com. © Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.) • Increased sympathetic arousal, which increases both stroke volume and heart rate • Increased buildup of pressure within the vessels To create temporary pressure, do the following: 1. Position the area where increased arterial circulation is desired, below the heart if possible: Seated, standing, and semireclined positions are most desirable. 2. A broad-based compression force is used against the tissue over the arteries. Begin close to the torso. If the arms are the target, begin where the arms join the torso (same for the legs). 3. Compression must be deep enough to close off the arteries so that pressure builds. The rate of on/off compression of the arteries is timed to the client’s heart rate, which is determined by the closest pulse rate in the area. For example, if the pulse rate is 60 beats per minute, the compression rate would be approximately 1 second on/1 second off—it is helpful to count, such as “1—(compress) and (release); 2—(compress) and (release).” 4. Pressure systematically moves distal toward fingers and toes. 5. The athlete can make a fist and can release or curl the toes and release at the same rhythm. Perform three or four repetitions in the area until the distal area is increased in temperature. 1. As with lymphatic drain, begin close to the torso and glide no more than 3 to 5 inches with the direction toward the heart to take advantage of the valve system in the veins. Systematically move toward the distal end of the limb. 2. Use kneading to move blood within capillary beds, dispersing it through soft tissue. 3. Have client actively contract and relax muscles and move joints in the area. Think of this action as similar to that of a pump. Passive joint movement can be used if necessary. It is effective to move the joint through its entire range of motion. 4. Repeat the entire sequence, then shift location a bit to address a different vein. 5. Calf muscles act as a secondary heart pump, especially influencing venous returning blood flow. The client can move the ankle in slow circles to activate this pumping action. This can also be taught as a self-help method. It is especially effective if the client lies on a slant board with the head slightly lower than the heart. This method is helpful even if the target area is not placed above the heart. 6. The respiratory pump supports venous return by channeling thoracic pressure during breathing. This is primarily caused by diaphragm action. Therefore it is important for the breathing mechanism to be normal. The following protocol is meticulous and detailed. It covers all current applications for lymphatic drainage that are based on physiologic mechanisms. It is presented in the ideal order of application to target lymphatic fluid flow. (Author’s note: I personally seldom perform the procedures as written here. Instead, I pick, choose, and modify. However, for learning purposes, I strongly suggest that you practice the protocols for both full-body application and local application until you are comfortable with the procedures, concepts, and outcomes.) This protocol addresses increased movement of interstitial fluid into the lymphatic capillaries without fibrosis. Management of fibrotic tissue is discussed on page 227. Contraindications for lymphatic drain massage include the following: • Compromised urinary or cardiovascular function, especially congestive heart or kidney failure • Systemic illness with symptoms such as fever, diarrhea, vomiting, and unexplained edema • Edema present in the acute phase of an injury (first 24 hours) • Increased physical activity such as a competition or a game followed by a 24- to 48-hour period of relative inactivity • Increased physical activity as above, but with insufficient recovery time (common in training camp schedules) • Increased water intake without appropriate electrolyte balance • Delayed-onset muscle soreness; sore all over, best described as achy • Stiffness that will not stretch out and is not clearly confined to a particular area • Skin and superficial fascia palpated as taut from increased hydrostatic pressure • Skin and superficial fascia palpated as boggy, spongy, soggy (increased fluid but not enough to push against skin, as previously described) • Difficulty palpating muscle fiber structure due to fluid accumulation overlay • Decreased definition of joints • Reduced range of motion of joints as a result of edema • Difficulty in lifting the skin and fascia from the surface layer of muscles • Deep, broad-based and narrow, superficially based types of compression; both are painful • Pitting edema and prolonged blanching of skin after compression • Drag on the skin and superficial fascia can create pockets of fluid that feel like small water balloons. • Reflexive methods are ineffective in resolving complaints. • Connective tissue applications may make symptoms worse, at least temporarily. 1. Increase fluid intake with proper electrolyte balance (50% water-diluted sport drink or pediatric fluid replacement drink such as Pedialyte). 2. Eat diuretic-type foods such as pineapple, papaya, berries, cucumbers, radishes, and celery. 1. Position the client on the back (supine) with arms and legs bolstered above the heart but with no areas of joints in a closed packed position (typically ends of range of motion). 2. Begin on upper thorax and use glide, knead, and compression to prepare the tissue. Goals are to increase skin pliability and connective tissue ground substance pliability, and to reduce any areas of muscle tension so that lymph capillaries and vessels are unobstructed. Continue into the abdomen, paying particular attention to abdominal and diaphragm muscles. 3. Mobilize the ribs by applying gentle but firm, broad-based compression beginning at the sternoclavicular joint, and work down toward the lower ribs. Make two or three passes, working from the sternum out toward the lateral edge. If an area of restriction is found, various methods can be used to increase mobility in the area. Compressing the restricted area while the client coughs is usually effective. Massage the intercostals. 4. Place client in side-lying position, and use glide, knead, and compression to continue to increase tissue pliability and rib mobility. Work from the iliac crests upward toward the axilla. Pay particular attention to the anterior serratus. Repeat on the other side. 5. Place client in the prone position (face down). Use glide, knead, and compression to increase tissue pliability and rib mobility. Begin at the iliac crest and systematically work toward the shoulder and neck. Do both left and right sides. 1. Reposition client in the supine position with arms and legs bolstered above the heart. 2. Place hand (a flat or loose fist) just below either clavicle, and compress and release. Repeat 3 or 4 times. Repeat method over sternum. Repeat method over the abdomen. Compress with exhale, release with inhale. Note: Repeat this procedure approximately every 15 minutes during the session (Figure 13-8). 3. Begin surface draining procedure. This process consists of dragging and sliding the skin to the tissue bind in various directions to pull on the microfilaments, while opening the ends of the lymph capillaries so that interstitial fluid can move from around cells into lower-pressure areas of lymph vessels. This needs to be done in a repetitive, rhythmic, slow manner, as with a pump. Drag skin to bind and let it return, drag skin again, etc. Each skin movement has a slightly different direction vertically, horizontally, diagonally, and circularly. The skin movement phase is a little longer than the release phase. Remember, the massage application is structured to mimic the pull of skin and fascia that would normally affect microfilaments attached to the lymphatic capillaries. Begin skin drag at the closest lymph node area, and work distal. This decongests and lowers pressure, allowing fluid to move from high pressure to low pressure. 4. Begin skin movement at the thorax midline above the diaphragm, and work toward the area under the clavicles. (Do both sides.) When this area is thoroughly addressed, repeat chest compression. 5. Continue with skin movement below the diaphragm, and change direction to drain toward the groin. 6. Have client do deep breathing while you gently but firmly knead the abdomen; then repeat chest compression. Compress on exhale, release on inhale. 7. Position client on side and repeat skin drag method, starting near the axilla, and drain from the waist up toward the axilla; below the waist, drain toward the groin, starting proximal to the region where drainage occurs. Do both sides. 8. While client is in the side-lying position, rhythmically compress the ribs (compress on exhale, release on inhale). 9. Place client in the prone position and drain again: Above the waist toward the axilla, and below the waist toward the groin. Compress the ribs in rhythm with the breathing.

Focused Massage Application

Indirect and Direct Functional Techniques

![]() Log on to your Evolve website to view additional examples of direct and indirect application.

Log on to your Evolve website to view additional examples of direct and indirect application.

Fluid Dynamics

Inflammation and Fluid Dynamics

Edema

The Lymphatic System

Lymphatic Drain Massage

Treatment

The Circulatory System

Massage Methods

Treatment

Increasing Arterial Circulation

Venous Return

Lymphatic Drain Massage

Assessment for Increased Interstitial Fluid Volume

Step-by-Step Protocol for Full-Body Lymphatic Drain Massage

Phase 1—Preparing the Torso

Phase 2—Decongesting and Draining the Torso (Figure 13-7)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Focused Massage Application

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue