Flexion Contracture Associated with Total Knee Arthroplasty

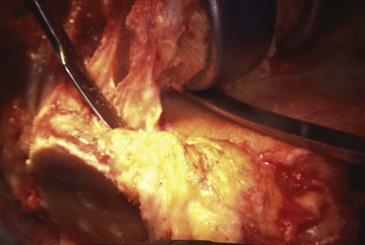

A fixed flexion contracture can result from several disease processes, including osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and posttraumatic arthritis. Often a common pathway starts with pain and leads to decreased motion and posterior capsular scarring. The scarring promoted by the inflammatory component of rheumatoid arthritis also plays a role. In arthrosis resulting from osteoarthritis or trauma, osteophytes play a significant role. Osteophytes develop posteriorly and in the intercondylar area (Figure 8-1). The intercondylar osteophytes form a mechanical block to extension, and they also alter cruciate kinematics. Osteophytes often overgrow the entire intercondylar notch, obscuring the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), in knees in which advanced arthritis is present and the anterior cruciate ligament is absent.

Posterior osteophytes can impede flexion because of impingement and scarring. They limit extension by scarring and tenting up the posterior capsule. When a flexion contracture becomes chronic and long-standing, secondary hamstring contracture can occur.

The goals of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are to provide adequate pain relief along with a knee that is stable and has a functional range of motion. The amount of knee flexion necessary for various activities of daily living is discussed in Chapter 7. The amount of knee extension necessary for a good functional result remains controversial. In a gait analysis study, Perry and colleagues reported in 1975 that −15 degrees of extension was necessary for a good functional result.1 In my experience, a permanent flexion contracture of 15 degrees after TKA may or may not be dysfunctional for the patient. On the other hand, I have yet to see a patient with a 10-degree flexion contracture report disability. In other words, −10 degrees of extension is acceptable, −10 to −15 degrees is borderline, and −15 or more is not acceptable.

Another controversy exists about how much of a preoperative flexion contracture has to be corrected at the time of surgery. The 1989 article by Tanzer and Miller is often quoted.2 They reported a small series of 35 TKAs with preoperative flexion contractures of less than 30 degrees. Only five of the knees in the series had flexion contractures greater than 20 degrees. The authors noted that the flexion contractures tended to improve after surgery and complete correction intraoperatively was not necessary. To an extent, I am in agreement with this, as discussed later. I think it is very important not to overcorrect for flexion contractures, resulting in a knee with hyperextension. In short, I would rather have a knee with a 5-degree contracture than one with 5 degrees of hyperextension. Similarly, I would rather have a knee with 10 or 15 degrees of a flexion contracture rather than 10 or 15 degrees of hyperextension.

Treatment Options

Treatment options for flexion contractures can be sorted into three categories: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative measures. Postoperative measures are discussed in the section on ancillary measures.

Preoperative Measures

Preoperative measures such as manipulation and serial casting or dynamic splinting are usually amenable only in patients with inflammatory arthritis without osteophyte formation (which can cause a bony block to extension). This type of treatment is especially appropriate for the adult patent or the patient with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis with bilateral hip and knee flexion contractures about to undergo hip and knee replacement surgery. In this situation, the hip arthroplasty is almost always performed first (see Chapter 10). While the patient is under anesthesia for the hip surgery, the knee is gently manipulated (stretched) for 3 to 5 minutes. Maximal extension is recorded, and a long-leg cast is applied at approximately 5 degrees less than the maximal extension. The cast must be well padded to avoid undue skin pressure. The following day, the cast is bivalved and lined as a resting cast. Ideally, the anesthetic used is an epidural, which can be left in place for several days, permitting daily manipulations with a new cast until progress ceases. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, I have seen preoperative flexion contractures of 90 degrees almost entirely corrected before attempting TKA (Figure 8-2). Obviously, this method is preferable to excessive bone resection to achieve an adequate extension gap. Because these patients are always osteopenic, care must be taken to avoid forceful manipulation and the possibility of a fracture (usually supracondylar). As noted earlier, this preoperative manipulation method is not appropriate for the osteoarthritic patient with a bony block to extension.

Intraoperative Measures

Various intraoperative measures can be used to correct a flexion contracture. It may be difficult to expose this knee, and the measures I recommend are covered in Chapter 7. The treatment options include removal of osteophytes both anteriorly and posteriorly. The posterior capsule can be stripped from both femur and tibia. Additional distal femoral resection is necessary for severe contractures. Occasionally, extra proximal tibial resection will be appropriate in the presence of patella baja. The amount of posterior tibial slope applied to the tibial resection should be zero rather than the usual 3 to 5 degrees. Finally, PCL substitution is helpful to facilitate release of posterior structures and correct posterior tibial subluxation, which either preexists in severe contractures or occurs as extension is achieved (Figure 8-3).

Osteophyte Removal

Anterior osteophytes in the intercondylar notch can build up and limit extension because of impingement. They will be removed with routine bone resection, allowing room for adequate extension to occur. Posterior osteophytes are more common in varus knees than valgus knees and more prevalent medially than laterally. The posterior capsule often contracts around the osteophytes, and their removal releases the posterior capsule enough in many cases to gain full extension with routine amounts of distal femoral bone resection when preoperative contractures are 15 degrees or less. The posterior osteophytes are best accessed and cleared after preliminary femoral and tibial preparation.

The trial femoral component is inserted without a trial tibial component. The knee is flexed and held upward with a bone hook. A curved  -inch osteotome is passed sequentially tangent to the metallic posterior condyles so that it removes any uncapped femoral bone and frees up the posterior osteophytes. The same maneuver is an efficient way to strip some of the posterior capsule from its femoral attachment. After the contour of the femoral component has been outlined on the posterior condylar bone, the trial femur is removed and the uncapped femur and remaining osteophytes are resected (Figure 8-4). An osteotome also can be used to strip the posterior capsule from the back of the tibia. I rarely do this maneuver, however, and gain most of the capsular stripping from the femoral side.

-inch osteotome is passed sequentially tangent to the metallic posterior condyles so that it removes any uncapped femoral bone and frees up the posterior osteophytes. The same maneuver is an efficient way to strip some of the posterior capsule from its femoral attachment. After the contour of the femoral component has been outlined on the posterior condylar bone, the trial femur is removed and the uncapped femur and remaining osteophytes are resected (Figure 8-4). An osteotome also can be used to strip the posterior capsule from the back of the tibia. I rarely do this maneuver, however, and gain most of the capsular stripping from the femoral side.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree