CHAPTER 19 Fixed-Bearing Uni

Long-Term Outcomes

Historical Background

Modern UKA implants have evolved from the early designs of MacIntosh and McKeever.1 These prostheses, introduced in the 1950s and 1960s, were metallic hemiarthroplasty implants designed to resurface only the tibial plateau. Early reports of both implants were encouraging; however, metallic hemiarthroplasty never gained popularity due to early loosening and to the advent of metal-to-plastic cemented arthroplasty.2

Classic Indications

In 1989, Kozinn and Scott3 published their classic article detailing the selection criteria for appropriate candidates for UKA. This involves consideration of the patient’s age, weight, occupational and recreational demands, range of motion, extent of angular deformity, and intra-articular pathology of the knee. According to their criteria, patients over 60 years old with a low-demand lifestyle are the best candidates. Patients should not be obese; ideally, patients should weigh less than 82 kg (180 pounds). They should have minimal pain at rest, a preoperative range of motion of at least 90°, and no more than a 5° flexion contracture. The angular deformity in the coronal plane should be less than 15° (10° of varus to 15° of valgus) and must be passively correctable to neutral after removal of tibial osteophytes. Intraoperatively, examination of the patellofemoral joint and opposite femoral compartment should not reveal exposed subchondral bone. In addition, the best results are obtained with intact cruciate ligaments. Patients with generalized inflammatory arthropathy are not candidates for UKA. Chondrocalcinosis is considered a relative contraindication for this procedure. Avascular necrosis is not contraindicated as long as adequate healthy bone is available to support the implants.

Expanding Indications: Patient Age, Activity, and Weight

Traditionally, UKA has been used to treat elderly, low-demand patients. However, the indications may be expanding. Pennington et al.4 in 2003 reviewed the results of UKA in patients 60 years of age or younger. These were all physically active patients. At the time of surgery, all patients were employed and participated in high-demand activities. Forty-five UKAs were reviewed at a mean of 11 years. Only three knees were revised. For the remaining 42 UKAs, 93% were rated as excellent. Survivorship was calculated at 92% at 11 years.

Similarly, Parratte et al.5 in 2009 reviewed 35 UKAs in patients less than 50 years old. They reported good clinical results and survivorship (80% at 12 years), but also noted that polyethylene wear is the major concern following UKA in this younger age group.

Kozinn and Scott3 believed that weight in excess of 82 kg should be a contraindication for a UKA. In support of this criterion, Berend et al.6 reported that body mass index (BMI = kg/m2) greater than 32 predicted early failure and reduced survivorship. The 82-kg cutoff weight limit continues to be challenged, however. Some cautiously suggest that the cutoff weight limit for a UKA could be raised to 90 kg.7 Naal et al.8 reported that BMI had no association with early clinical outcome or implant failure. Tabor et al.9 also suggested that youth and obesity should not be considered contraindications to UKA. In fact, in their analysis, obese patients had better survivorship than nonobese patients at 20 years.

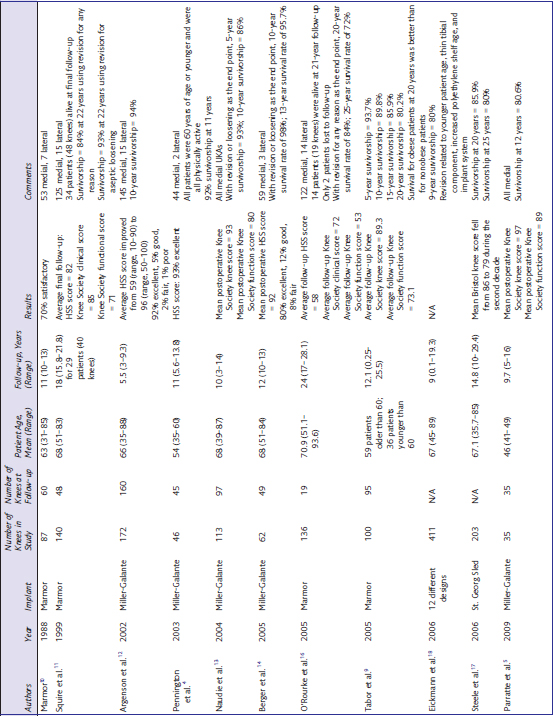

UKA Long-Term Results (Table 19–1)

Much of the published literature combines medial and lateral UKAs. One of the earliest long-term outcome studies of fixed-bearing UKAs was by Marmor in 1988.10 This included 60 Modular Marmor arthroplasties, 53 medial UKAs, and 7 lateral UKAs. At a minimum of 10 years’ follow-up, patients maintained a 70% satisfactory result.

Table 19–1 Long-Term Results of Studies Including Both Medial and Lateral Fixed-Bearing Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

Over the last decade, there have been numerous studies demonstrating the excellent long-term outcomes and survivorship of more modern fixed-bearing UKAs. Squire et al.11 reviewed 140 consecutive Marmor cemented UKAs with an all-polyethylene tibial component inserted between 1975 and 1982 and published their long-term outcomes. At final follow-up, 34 patients (48 knees) were alive and available for review. Only four patients (four knees) were lost to follow-up. There was a minimum of 15 years’ follow-up on 29 patients (40 knees). At this length of follow-up, 12.5% of UKAs required revision. The survivorship analysis showed encouraging results. Using revision surgery for any reason as an end point, survivorship was 84% at 22 years. Using revision surgery for aseptic loosening as an end point, survivorship was 93% at 22 years. Disease progression in the contralateral compartment and tibial subsidence with wear were the major long-term problems. Overall satisfaction, however, was excellent in these patients. In 2002, Argenson et al.12 reviewed 160 UKAs (145 medial and 15 lateral) with an average of 5.5 years’ follow-up (range, 3–9.3 years). Mean patient age was 66 (range, 35–88). Average Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score improved from 59 (range, 10–90) to 96 (range, 50–100). Ninety-two percent of these knees were graded as excellent. The 10-year survivorship was 94% with revision for any reason or radiographic loosening as the end point.

Naudie et al.13 in 2004 reported on their results from 113 medial UKAs. They noted excellent pain relief and restoration of function with a mean follow-up of 10 years. With revision or radiographic loosening as an end point, survivorship was 93% at 5 years and 86% at 10 years. Mean Knee Society knee and function scores improved at final follow-up to 93 and 80 points, respectively. In 2005, Berger et al.14 reported on 62 consecutive UKAs with a minimum of 10 years’ follow-up. Mean postoperative HSS score was 92, with 92% good to excellent results. The 10-year survival rate was 98%. In addition, Berger et al.15 reported that, at 10 years’ follow-up, patellofemoral symptoms were present in only 1.6% of patients. However, at 15 years’ follow-up, 10% of patients had moderate to severe patellofemoral symptoms. Although in this series progressive patellofemoral arthritis was the primary mode of failure, clinical results and survivorship were excellent. O’Rourke et al.16 in 2005 reported on a series of 136 consecutive UKAs with a minimum 21 years’ follow-up. With revision for any reason as the end point, survivorship was 84% at 20 years and 72% at 25 years. The patients most at risk for revision were younger at the time of surgery. Although the clinical and functional scores in this group were relatively low at this long-term follow-up, it is important to note that this was a group of elderly patients with multiple medical and orthopaedic comorbidities. Steele et al.17 reviewed the Bristol database to determine survivorship beyond 10 years of a fixed-bearing UKA. Although the mean Bristol knee score fell from 86 to 79 during the second decade, survivorship was satisfactory into the second decade (85.9% at 20 years and 80% at 25 years).

A review of the literature highlights the important role of implant design in fixed-bearing UKA outcomes. A paper by Eickmann et al.18 in 2006 reviewed 411 fixed-bearing medial UKAs placed by a single surgeon in the 1980s to 1990s. There was a 9-year survivorship of 80%. This result was highly dependent on implant design. Nine-year survival improved to 94% when tibial component thickness was greater than 7 mm and polyethylene shelf age was less than 1 year. Factors that were associated with revision included younger patient age, thinner tibial component, increased polyethylene insert shelf age, and implant system utilized.