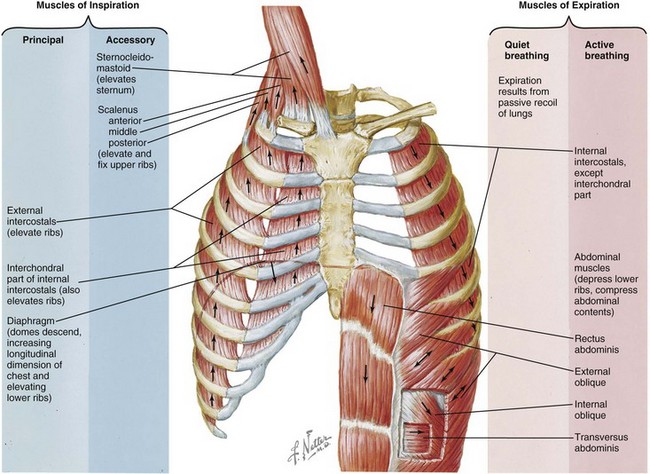

Chapter 5 After completing this chapter, the student will be able to perform the following: 2 List the benefits of exercise. 3 Describe how exercise is part of a fitness program. 4 Explain the importance of proper breathing to fitness. 5 List and explain the components of a fitness program. 6 Explain intensity, duration, and frequency as these terms relate to a conditioning program. 7 Explain why it is important to include endurance, aerobic exercise, adaptation, and training stimulus threshold in a therapeutic exercise program. 8 Explain the importance of core strength as it relates to functional training. 9 List the major energy-producing systems in the body and their implications for fitness programs. 10 Identify the physiologic changes that occur with exercise. 11 List and describe the three main components of an exercise program that targets fitness. 12 Incorporate strength training into physical fitness. 13 Describe how flexibility supports an exercise program. 14 Explain the transition from fitness training to sport-specific training. Benefits from physical activity include the following: • Decreased risk of death from coronary heart disease and of developing hypertension, colon cancer, and diabetes • Improved muscle strength and stamina • Improved mood and increased general feeling of well-being • Decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression • Increased control of pain and joint swelling associated with arthritis/arthrosis • Promoting weight loss as a result of increasing calories burned • Controlling blood pressure through exercise and diet • Improving cholesterol levels. In particular, aerobic exercise raises blood levels of HDL cholesterol. HDL cholesterol carries LDL cholesterol to the liver, preventing it from clogging arteries. • Reducing the tendency for smoking and other detrimental behaviors, because exercise calms nervous tension Proper breathing at all times is important. If breathing is not effective, the ability to exercise is compromised. Breathing patterns, both functional and dysfunctional, serve as a direct link to altering autonomic nervous system patterns, which in turn affect endocrine function and mood, feelings, and behavior. Especially when working with athletes, the breathing function may be a causal factor in many soft tissue symptoms (Figure 5-1). FIGURE 5-1 Respiratory muscles. Contraction of the diaphragm is the main factor producing inspiration during normal, quiet breathing; expiration is a passive process in this type of breathing, caused by passive recoil of the lungs. Active breathing requires the activity of additional muscles and involves energy expenditure for both inspiration and expiration. (Netter illustration from www.netterimages.com. ©Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.) If the athlete does not balance oxygen/carbon dioxide levels through increased activity levels, overbreathing in excess of physical demand can occur. Patterns of breathing dysfunction (overbreathing) are quite common in the athletic population. This can occur for a variety of reasons, including inability to achieve parasympathetic dominance (relaxation) after training or competition; dysfunction of respiratory muscles (Box 5-1); or restricted structure, particularly of the ribs and thoracic vertebrae. Assessment for functional breathing problems is very important. If breathing issues are apparent, the athlete should be referred to his or her physician for evaluation to rule out a serious pathology such as asthma, chronic bronchitis, and cardiac and endocrine disorders. Those with cardiac and/or respiratory conditions are prone to breathing dysfunction. To recognize and then develop an appropriate treatment plan, a brief overview of breathing functions is presented here, and an assessment and treatment plan are suggested with a basic protocol in Unit Two. It is strongly suggested that the text Multidisciplinary Approaches to Breathing Pattern Disorders1 be obtained and studied thoroughly.

Fitness First

Being Fit

Breathing

Overview of Breathing Function

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree