Chapter 18 Fibromyalgia syndrome and chronic widespread pain

KEY POINTS

Treatment programmes should be multimodal, addressing the physical and psychological aspects of the condition

Treatment programmes should be multimodal, addressing the physical and psychological aspects of the conditionINTRODUCTION

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a common chronic muscular pain syndrome that is frequently treated by physiotherapists and occupational therapists. The classification criteria for FMS proposed by the American College of Rheumatology (Wolfe et al 1990) are

Although chronic musculoskeletal pain associated with tenderness, fatigue, sleeplessness and general malaise has been recognised for centuries (Smythe 1989), the authenticity of FMS generates (often vigorous) debate. It is argued that the FMS construct is flawed. The overlap between other conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome and the absence of distinct pathological markers in FMS means the condition cannot be considered a discrete disorder. In the UK, researchers examined the relationship between tender points, pain and symptoms of distress such as depression, fatigue, and sleep quality. It was found that most participants with chronic widespread pain (CWP) had fewer than 11 tender points, and counts of 11 or more tender points were also found in participants with regional pain and no pain. Additionally there was a significant association between tender point count and scores for depression, fatigue, and sleep problems, independent of pain (Croft et al 1994). Consequently these authors concluded that high tender point count was a measure of general distress, and argued that the combination of CWP and high tender point count represented one end of a continuum of pain and tender points rather than a particular clinical condition.

In some respects the debate over the ‘existence’ of FMS is irrelevant. Patients with FMS or CWP may or may not have a high tender point count. Those that do generally are more distressed and have more somatic symptoms (McBeth et al 2001). However, the strength of the ACR 1990 criteria is that they provide clinicians and researchers with a simple, uniform case definition for clinical investigation that has a high sensitivity (88.4%) and specificity (81.1%) for FMS (Wolfe et al 1990). For this reason the diagnostic label of FMS is useful.

PREVALENCE OF FMS AND CWP

The prevalence of FMS, using the ACR criteria is 2% overall but it is much more common in women (3.4%) than men (0.5%) and prevalence increases with age (Wolfe et al 1995). No population studies of the prevalence of FMS have been carried out in the UK, although the point prevalence of CWP has been reported to be 11–12%. When the more stringent ‘Manchester definition’ of CWP is used, the figure is 4.7% (Hunt et al 1999). The diagnosis of FMS appears to be increasing in the UK. However, this is perhaps due to a greater acceptance of the condition among GPs rather than a real increase. Additionally, wide geographical variations in diagnosis exist (Gallagher et al 2004, Hughes et al 2006).

The prognosis of FMS and CWP is poor (Papageorgiou et al 2002). It has been reported that when patients are followed up over a prolonged period, there was little change in pain, functional disability, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and psychological status from baseline. Once CWP is established it is likely to persist, to some extent, in most people.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND SPECIAL TESTS

Patients with FMS or CWP present with many symptoms and often have other musculoskeletal conditions. It is important such conditions are adequately screened to avoid unnecessary morbidity. Rheumatological conditions mimicking FMS include: mild systemic lupus erythematosus, polyarticular osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, hypermobility syndromes and perhaps osteomalacia. Non-rheumatological diseases mimicking FMS include neoplastic and neurological diseases such as: multiple sclerosis, thyroid dysfunction, chronic infections, and some psychiatric conditions. When considering a diagnosis of FMS all other possible diagnoses must be excluded. Standard blood tests include: full blood picture, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, nuclear antibody profile, creatine kinase, thyroid function tests and C2 +.

PATHOLOGY OF FMS AND CWP

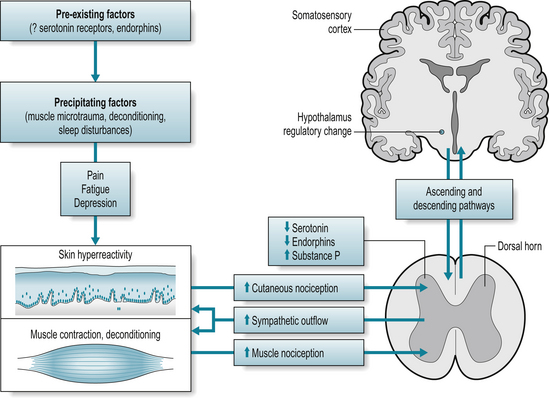

A summary for the possible pathophysiology of FMS and CWP is given in Figure 18.1 and the process considered below.

NEUROENDOCRINE DYSFUNCTION

FMS could be classified as a ‘stress related syndrome’. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) plays a critical role in the body’s response to threatening stimuli. Dysfunction of the normal stress response can lead to the initiation and maintenance of FMS symptoms. In FMS a number of studies have investigated alterations of the HPA axis with some studies reporting elevated evening basal plasma cortisol levels and others reporting decreased 24-hour urinary free cortisol (Wingenfeld et al 2007). Alterations in the stress-response systems are thought to contribute to the development and maintenance of FMS and CWP (Crofford & Clauw 2002).

ABNORMAL PAIN PROCESSING

FMS may be related to altered central nervous system (CNS) processing of nociceptive stimuli. Noxious insult normally stimulates particular primary afferent nerve fibres. This information is then transmitted via the dorsal horn of the spinal cord to the thalamus and cerebral cortex where nociceptive information is consciously perceived, and interpreted in light of past experience. Injury and the activation of primary afferents, specifically A-delta and C fibres, results in the release of an ‘inflammatory soup’ which includes bradykinin, prostaglandins, histamine, potassium, adenosine, serotonin, substance P, and cytokines. The effect of this on nociceptors is hypersensitivity to noxious stimuli, associated with depolarisation and spontaneous discharge of nociceptors, commonly referred to as peripheral sensitisation (Bennett 2000). Increased neuronal barrage from peripheral pain generators to the CNS can result in increased excitability of spinal cord neurons, i.e. central sensitisation, and is responsible for increased spontaneous activity of the dorsal horn neurones, increased excitability to afferent inputs, prolonged after-discharge, and expansion of peripheral receptive field of the neurones of the dorsal horn.

The experience of allodynia (a painful response to a non-painful stimulus) and hyperalgesia (an increased response to a stimulus which is normally painful) in FMS are thought to be expressions of peripheral and central sensitisation in FMS. Vaerøy et al (1988) and Russell et al (1994) demonstrated a three-fold increase in the concentration of the neurotransmitter substance P in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with FMS. Substance P modulates nociception and signalling intensity of noxious stimuli and so increased levels play a critical role in FMS symptoms, in conjunction with other neurotransmitters, e.g. serotonin. This neurotransmitter plays a key role in mood, cognition, deep sleep, and circadian and neuroendocrine rhythms, and also inhibits release of substance P in the spinal cord in response to peripheral stimuli. Reduced serotonin levels (or its precursor tryptophan) occur in FMS. Low serotonin and increased substance P could amplify pain-ful sensory signals.

Commonalities amongst people with FMS or CWP are shown in Box 18.1. Other factors that have been linked to FMS include: being divorced, lower educational achievement, low household income, physical stress at work, being widowed, being disabled, and a family history of chronic pain.

ASSESSMENT OF THE PATIENT IN PAIN

ASSESSMENT PROCEDURES FOR PHYSIOTHERAPISTS AND OCCUPATIONAL THERAPISTS

A full history, including past medical history and previous investigations, should be taken. It may be necessary to contact the referring physician to get a comprehensive picture of the patient’s past medical history. The therapist should enquire about the history of the current episode. As it can sometimes be difficult to establish the ‘current’ episode with chronic pain conditions, note should be taken of when increasing problems started, precipitating factors and management to date. It may be necessary to conduct the assessment over several appointments because of activity tolerance and pain. As with all conditions it is important to ensure that ‘red flags,’ or indicators of serious pathology, are excluded, consequently the standard ‘mandatory’ questions should be asked (Box 18.2).

BOX 18.2 Mandatory questions to identify ‘red flags’

General health: any rheumatoid arthritis, ischaemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, history of cancer, recent surgery

General health: any rheumatoid arthritis, ischaemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, history of cancer, recent surgeryPain

Identify with the person, on a body chart, areas of pain, paraesthesia or numbness, factors aggravating and easing pain, diurnal variation, and severity of pain.

PHYSIOTHERAPY ASSESSMENT

A full description of joint examination techniques can be obtained from Petty (2006). However, the physiotherapist should ensure each area of pain and possible source of pain is assessed and details recorded (Table 18.1).

Table 18.1 Detailed recording of pain areas and pain sources

| Local observations | Bony contours Colour changes Swelling Muscle atrophy Muscle spasm |

| Active and passive range of movements | Willingness to move Pain Range Joint end feel |

| Static muscle tests | Pain Muscle strength Muscle weakness |

| Special tests | Additional testing (e.g. ligaments) should be carried out as appropriate |

| Palpation | Painful areas should be gently palpated noting pain, temperature, and sympathetic changes such as sweating. Palpation should be conducted with regard to individual’s increased sensitivity to pressure (allodynia and hyperalgaesia) |

| Other symptoms | Sleeplessness, fatigue, anxiety, and depression should be discussed and their impact recorded |

Manual tender point survey

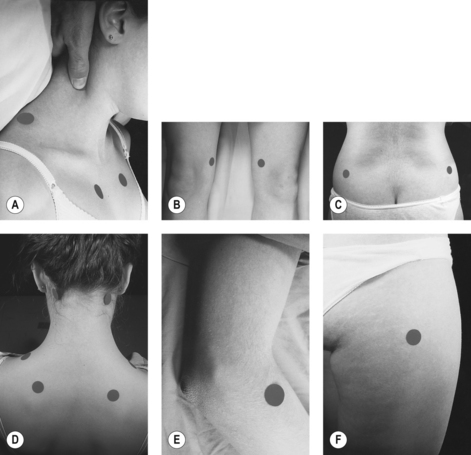

Tender points (Fig. 18.2A-F) should be examined manually or with a pressure algometer (Fig. 18.3). Tender points are considered ‘positive’ if the patient complains of pain at approximately 4 kg/cm2 of pressure, which is about the pressure required to blanch the nail bed of the thumb. Okifuji et al (1997) have described a standardized procedure for examining tender points, which is described in a booklet and CD developed by Sinclair et al (2003).

Figure 18.2 (A-F) Locations of the nine pairs of tender points for diagnostic classification of fibromyalgia.

Adapted from Ch. 62 Figure 62.1 p702 with permission from: Goldenburg DL 2003 Fibromyalgia and related syndromes. In: Hochberg MC et al (eds.) Rheumatology (3rd edn), Elsevier, London.

Cardiovascular fitness

Often people with FMS and CWP are sedentary and deconditioned. Their baseline fitness should be identified and used in future exercise prescription. The 6-minute walk test has been demonstrated to correlate significantly with aerobic fitness in patients with FMS (King et al 1999).

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY ASSESSMENT

Occupational therapists assess the functional impact of FMS, and factors limiting performance including: physical, psychological, social and environmental influences. Extending the assessment over more than one session will encourage a therapeutic relationship, initially focusing on activities of daily living, and later progress to more sensitive issues such as psychological changes.

Physical assessment

The following should be observed and recorded:

Upper limb function can be observed through:

A more detailed examination may be necessary for some. The Gait Arms Legs and Spine (GALS) assessment is a relatively quick physical assessment to perform. Details of how to perform this and a training video are available at www.jointzone.org, in the musculoskeletal examination section.

Psychological assessment

Establishing rapport and developing a therapeutic relationship assists the therapist in evaluating psychological status, and careful observation and pertinent discussion can give an indication of psychological well-being (Box 18.3).

Social/environmental assessment

A social/environmental assessment will contextualise an individual’s roles (Box 18.4). Given the potential complexity of social situations it may be appropriate to gain understanding as the intervention progresses rather than on initial assessment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree