1 Introduction This introductory chapter is intended to survey the meanings and problematic of the wish for a child in the context of its social and cultural environments. We have found that ethical-moral views colored by social as well as religious paradigms significantly affect reproductive and sexual behavior. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) draws not only on the experiences of a complex treatment system transmitted over 2500 years, but also, a holistic view of the individual that is rooted in notions from our time and context. TCM can be utilized in fertility consultations as an alternative as well as supplement to other medical methods. In this context, it benefits from the fact that the unusual reception of TCM in the West has integrated aspects of psychological diagnosis and care, in addition to the therapeutic application of acupuncture/moxibustion and Chinese medicinals, into a special treatment concept. Involuntary childlessness refers to a state that is characterized by the condition of barrenness (also called infertility or sterility). In 1967, the Scientific Group on the Epidemiology of Infertility of the WHO recognized involuntary infertility (inability to fertilize or conceive) as a disease. According to the WHO definition, infertility/sterility is diagnosed when a couple is unable get pregnant against their explicit wishes after more than 24 months in spite of regular unprotected sexual intercourse (ICD-10 Diagnosis: Female sterility [N97.x], male sterility [N46]). In Germany, 15% of all couples have problems with fertility.16 In the United States, a 2002 survey by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention found that about 12% of women of reproductive age (7.3 million) had difficulty getting pregnant or carrying a baby to term. It is becoming evident that fertility problems will increase further in the coming years because women, those with a higher level of education in particular, are delaying the question of having a child until the time that biomedicine tends to associate with approaching menopause. Meanwhile, in Germany, 40% of all women aged 35–39 and 43% of women aged 40–44 remain childless from choice. In the United States, the figure is 41.6% for all women of child-bearing age. (Table 1.1 shows the proportion of childless women among persons born in 1955 in various EU countries.) From 1961–1999, the average age of prima-paras (first pregnancies) in Germany rose from 24.9 to 28.9, and the figures are similar in many other developed countries. One reason for this development is the fact that people prioritize economic and societal success when planning their personal lives. The limit for this goal keeps getting pushed forward into the years between ages 30 and 40, as a result of which there is hardly any time left in this short span of 10–20 years for the attention that could be focused on producing a child. Another aspect, though, is the notion that the “wish child” is supposed to serve as much as possible the fulfillment of parents’ needs for maximum social conformity and the completion of their own life plans, hence requiring it to arrive as “planned.” Behind this idea we often find a mechanistic understanding of the extremely complex process that can ultimately lead to the creation of new life; an understanding that is further promoted and propagated by artificial techniques regardless of their minute success rates. Success rates refer to the so-called “baby take-home” rate. In Germany, this amounts to an average 16% per embryo transfer. According to the German IVF Register 2002, this comprised 17.49% for IVF, 19.79% for ICSI, and 10.28% for the re-implantation of originally cryoconserved ovums in the pronuclear stage. Hence, we see a baby take-home rate of a good 15% per started cycle in IVF (in vitro fertilization) and ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection).5 In 2006, Canadian clinics achieved a live birth rate of 27% for IVF treatments.*

1 Fertility Treatment—Its Social and Cultural Context

Andreas A. Noll

Reduced Fertility—Epidemiology—Causes

| Country | Proportion |

| Germany (all states) | 22% |

| Finland | 18% |

| Netherlands | 17% |

| United Kingdom | 17% |

| Denmark | 13% |

| Ireland | 13% |

| Sweden | 13% |

| Belgium | 11% |

| Spain | 11% |

| Italy | 11% |

| France | 8% |

| Portugal | 7% |

Source: Eurostat 2001; quoted after Engstler and Menning.10

This illusion of realizability at will reduces the process of fulfilling the wish for a child to a clockwork mechanism that merely has to be set in motion at the crucial time. Nevertheless, many couples are greatly disappointed when they find that their wish for a child does not come true at the intended time.

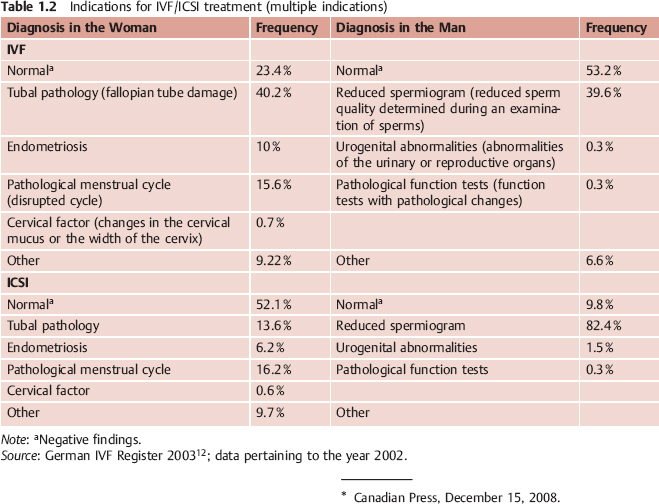

After sometimes decades of birth control and the strains of work (stress, shift work, etc.) and the environment (toxins, nutrition, etc.), women’s hormone production and menstrual cycle and men’s sperm production are not like those of a 25-year-old (Table 1.2). It is assumed that the release of stress-related hormones (like prolactin or cortisol) can trigger endocrinologic or immunologic mechanisms (such as antibodies in the cervix), which in turn lead to reduced fertility. In addition, the role of social security as the foundation for long-term life planning has been limited considerably by unemployment as well as increasing demands for mobility and flexibility.

These developments have given rise to a variety of different assumptions: from a threatened “extinction of the population” and the “social duty” of parenthood, to the insinuation that voluntary childlessness signals egocentrism and antisocial behavior. Parenthood, by contrast, is presumed to signify maturity and a sense of responsibility towards society at large. Involuntarily childless couples may therefore suffer stigmatization and often feel pushed into social isolation because of their problems.

Due to an attitude of high personal hopes, an age-related reduction in fertility, and social expectations, many couples develop an overwhelming desire to have a child, for the sake of which they are prepared to make many personal or financial sacrifices. “Most commonly, this group is composed of couples who are extremely successful in society, highly oriented towards social norms, and with a great need for functionality and self control.”6

Reproduction and Sexuality

In the West—Christianity, Enlightenment, and the “Pill”

Sexuality is an innate power that gives humans the possibility to gain pleasure. This energy reaches its peak with the onset of sexual maturity. This does not mean, however, that it is not present before or after this time span. A child also gains pleasure, just as older people past their reproductive age can have a fulfilled sex life. In this respect, human sexuality is something that can first be lived out independently from reproduction. In our context, however, it is important that sex—irrespective of autoerotic activities—is per se directed at a partner and in this aspect acquires a social and cultural dimension.

In the recent past, the “sexual revolution” and the contraceptive pill in particular have separated sex from reproduction. “Free love” created the possibility of having sex without begetting a child, while modern biomedicine now promises a child without sex. We must apparently distinguish here between two terms—sexuality and reproduction—which in fact exist separately from each other but are nevertheless intimately interwoven.

The close connection between sexuality and reproduction was formed in our culture under the influence of Christianity. Hinduism likewise postulates “chastity in marriage,” as a result of which sexuality was shifted into the realm of extramarital activities like prostitution, a process that was and is certainly also found in the Greco-Roman-Christian cultural complex as a result of sexual asceticism.

The Christian Church proceeded from a black-and-white image of woman as holy mother or evil temptress. However, this development only occurred with the increasing institutionalization of Christianity into a church, while women enjoyed a status of fundamental equality in the early stages of this religion. In this regard, early Christianity was influenced by stoicism, whose basic premises were the absence of passion, the primacy of reason, virtue, and a lifestyle in correspondence with nature. Philon of Alexandria, for example, a Greek Jewish theologian, postulated that sexual intercourse in marriage should only take place for the purpose of producing offspring, not for the sake of pleasure.

Similarly, according to Clement of Alexandria (2nd- 3 rd century CE), marital sex should only take place for the sake of reproduction, and man and woman should live like brother and sister the rest of the time. Particularly significant for Christian moral theology was Aurelius Augustinus who branded any type of pleasure as sinful and evil (4th- 5th century CE). In early Greece of the 6th century CE, Pythagoras, as well as later Xenophon, Plato, Aristotle, and Hippocrates alike, shared the view that excessive sexual intercourse was harmful. Influenced by these Greek traditions, the apostle Paul finally relegated women to the above-mentioned roles. For centuries thereafter, the “evil” prostitute and sexual temptress on the one side, coexisted with the “holy” mother in the service of reproduction on the other.

The notion that the male seed (just like a seed of grain) already contained all life and that women therefore merely served as a fertile field survived into the 17th century. Thomas Aquinas (13th century) imagined the sexual act in paradise without any sensation of pleasure and considered matrimony as the will of God, as long as it serves the begetting of children. Martin Luther also saw sexual pleasure as resulting from the Fall of Man, but tolerated marriage also “for the sake of harlotry,” as a medicine against unchastity. This purposive-rational attitude continues to survive in Calvinism and in radical Puritanism (in the United States).

In the course of enlightenment, which demanded in the 17th and 18th centuries, a “free man, absolved from a self-imposed immaturity” (Kant, 1724–1804), sexuality experienced a partial redefinition in the relationship between man and woman, in the sense that it stressed emotional, sensual relationships based on respect and mutuality. This development was continued by the Romanticists in the 18th century.

A very different view, however, was taken by Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). In his work and on the basis of psychoanalytic reasoning, he created new notions about sexuality that have deeply influenced our thinking even to this day. Influenced by mechanistic ideas, terms like “drive,” “suppression,” “the unconscious,” and so on, are deeply anchored in our use of language. Freud “mechanized” and (pathologized) sexuality as a source of neuroses as well as of cultural developments. Many couples in fertility treatment appear to give more priority to these aspects than to a lively sexuality; and sexual intercourse itself as well as fertilization become increasingly mechanized in the course of the various attempts, and are performed with a purposive attitude.

In the East—Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism, and Modern China

In China as well, issues of reproduction and sexuality have been determined significantly by the culture as a whole, which since the 5th century BCE, was shaped by the two great religious-philosophical currents, namely Confucianism and Daoism, and later, since the 1st century CE, by Buddhism.

Confucianism

Founded by Kongzi in the 5th century BCE, Confucianism is rooted in a worldview that defines the individual as part of society, and not only on a synchronic plane, that is, during the person’s lifetime, but also in terms of obligations towards ancestors and descendants. All individual efforts should serve first and foremost the creation and preservation of a good and just society by a system of mutual, carefully graded rights and responsibilities. The personal fulfillment of wishes and claims of the individual was secondary to this, unlike in the West, where the individual was the governing force since Plato. All human efforts, hence also sexuality, had to be subordinated to this overarching benefit to society as a whole. Reproduction assumed a central role until the modern age, especially since neo-Confucianism developed around the 12th century in the Song dynasty. Concepts of sexuality, on the other hand, were primarily developed in Daoism.

Confucianism, which should in fact be considered a philosophical and social concept rather than a religion, moreover incorporated ancestor worship, practiced in China since thousands of years. This tradition is based on a system of mutual obligations within families, far beyond the present existence. The “begetting of sons” (see pp. 18ff) was therefore an indispensable part of this system. With regard to reproduction, Confucian thought also influenced the other two great religions in China, Daoism and Buddhism.

Daoism

Daoism is designed much more loosely than Confucianism. We can distinguish between several developments since its creation by Laozi and Zhuangzi, most likely contemporaries of Kongzi:

- sociopolitical developments (Laozi)

- philosophical teachings (Zhuangzi)

- a religion with a particular world of deities (assimilated from popular religion, which also included the fangshi [“magicians”] widely popular until the Qing period)

- the ability to cultivate life (yang sheng)

- religious cult with sometimes sexual practices, and so on

In particular, with regard to the aspect of “cultivating life” (yang sheng), which included efforts to achieve longevity and immortality, numerous strategies were developed in the areas of sexuality and reproduction. More details on this topic and on Confucianism can be found in the contributions of Dagmar Hemm (pp.18ff).

Buddhism (Mahayana)

For Buddhism, all life is suffering. This suffering has four causes, of which the second cause is desire, or thirst, that is, for the so-called “lusts of the five senses,” for existence, for becoming, and for non-existence. The goal of Buddhism is liberation from the eternal cycle of rebirth. This is achieved by practicing the “eight-fold path of right conduct”:

- right insight

- right intent

- right speech

- right actions

- right livelihood

- right efforts

- right mindfulness

- right concentration

In this context, Confucian ideas about descendants and ancestors are just as irrelevant as Daoist ideas about longevity and immortality. Hence, Buddhist monks are not allowed to touch women or spend time with a woman in a secret or non-public place, let alone engage in sexual intercourse. In Buddhism, sexuality is not seen as reprehensible per se, but only as part of general badness that must be overcome because it stands in the way of enlightenment.

We also need to mention that Tantric Buddhism, a school of Buddhism, consciously cultivated sexuality in “red” or “left-handed” Tantra and engaged in sexual practices to unite the polarities. But not all forms of Tantrism include real sexual intercourse, such as Buddhist and Hindu Tantrism. During the time of Kublai Khan (1216–94 CE), this school exerted considerable influence, which, however, declined afterwards and partly continued to exist in turn in Daoist communities like the Quanzhen order.

Syncretism

Throughout Chinese history, the combination of these three great philosophical-religious currents in a great variety of ways led to alternating sexually liberal and repressive periods, as happened for different ideological reasons in European history as well.

Modernity

Since the 17th century, that is, with the end of the Confucian-influenced Ming dynasty and the beginning of the Manchu Qing dynasty, the influence of Western thought has grown, especially due to the activities of mostly Protestant missionaries. Nevertheless, their influence has remained marginal until today.

With the foundation of the socialist People’s Republic of China in 1949, and most vividly during the Cultural Revolution since the middle of the 1960s, the large family with many children was propagated as a socialist ideal. The subsequent “one-child policy” successfully slowed down population growth, sometimes with abortive methods up until the last months of pregnancy that are quite severe from a Western perspective. The continued existence of the “wish for sons” (see pp. 18 ff), however, has promoted a selective practice of abortions on the one hand, and the intensive implementation of fertility-enhancing methods from Western and Traditional Chinese Medicine, on the other.

Integration: TCM

TCM as practiced here in the West is rooted in a complex medical system with 2500 years of transmitted experience. This system is linked inseparably to Chinese culture and history. The knowledge and ideas that stem from our own cultural background serve as an additional source. The process of familiarizing ourselves with ideas that are initially foreign to us, however, crystallizes the relativity of our own thinking. New horizons can open up when we surmise the dilemma of Western thinking—to mention just a few, the ethics debate over gene technology, abortion, or pre-im-plantation diagnosis—as a dead-end inherent in the system. Rooted in our time and environment, the initially vague discomfort that we experience towards mechanistic and particularizing ideas gives rise to a longing for a holistic conception of the human being. This desire originated in and becomes more concrete precisely in the acceptance of or at least confrontation with, even if only partial and quite selective, an often exoticized and glamorized paradise of the East; it can thus point to new perspectives. This synthesis of East and West, which might arise in a few branches, can offer new impulses here as there.

Reception—Opportunities

The comments at the beginning of this chapter clearly show that modern biomedicine and complementary medicine, here referring to TCM, can both contribute to our efforts at fertility treatment. Chinese medicine offers us the chance to build bridges between the deconstructed view of the human body in the West and the fragments of ancient Chinese medicine that will have to be at least partially reconstructed. The reason for this is that it was also influenced by Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, even if not always in a way that we find desirable. In this context, the deconstructed view of the human body in the West concerns on the one hand the relationship between man and woman, in the private and public realm alike, which covers innumerable different areas. On the other hand, however, it also concerns desolate notions about the functioning of a body or its individual parts with neither connection to spirit or soul nor to other parts of the organism. In general, the goal of medicine should be to restore health and thereby the unimpeded life of the organism in all aspects, internally and externally. This goal should be our first maxim, especially in a process as sensitive and affected by multilayered aspects as the creation of new life, of a new autonomous being. Interventions into this extremely complicated set of rules may be necessary, but should always be undertaken with the following quote from Goethe’s (1797) poem “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” in the back of the mind:

- “I have need of Thee!

- From the spirits that I called,

- Sir, deliver me!

- “Back now, broom,

- into the closet!

- Be though as though

- wert before!

- Until I, the real master

- call thee forth to serve once more.”*

Bibliography

- Beier KM, Bosinski HAG, Loewit K. Sexualmedizin. 2nd ed. Munich: Urban & Fischer; 2005.

- Brand M von. Der Chinese in der Öffentlichkeit und der Familie, Wie er Sich Selbst Sieht und Schildert. Berlin: Reimer; ca. 1910.

- Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden (editor). Sex. Vom Wissen und Wünschen. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz; 2001.

- Eberhard W. Guilt and Sin in Traditional China. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1967.

- Felberbaum R. Fortpflanzungsmedizin: Methoden der Assistierten Reproduktion Werden Sicherer. Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 2004;101:A-95/B-83/C-82. http://www.aerzteblatt.de/v4/archiv/artikel.asp? id= 40 109 (accessed April 24, 2009).

- Gebhard U, Hößle C, Johannsen F. Eingriff in das Vorgeburtliche Menschliche Leben. Neukirchen-Vlyun: Neukirchener Verlagsgesellschaft; 2005.

- Goldin PR. The Culture of Sex in Ancient China. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press; 2002.

- Granet M. Die Chinesische Zivilisation. Familie, Ge-sellschaft, Herrschaft. Von den Anfängen bis zur Kaiserzeit. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp; 1985.

- Kang C. Man and Land in Chinese History. An Economic Analysis. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1986.

- Leutner M. Geburt, Heirat und Tod in Peking. Berlin: Reimer; 1989.

- Linck G. Frau und Familie in China. Munich: Beck; 1988.

- Rieder A, Lohff B (editors). Gender Medizin. 2nd ed. Vienna: Springer; 2007.

- Ruan F-F. Sex in China. New York: Plenum Press; 1991.

- Schnitzer C (editor). Mannes Lust & Weibes Macht. Dresden: Sandstein; 2005.

- Strauß B, Beyer K. Ungewollte Kinderlosigkeit. Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. 2004;20.

- Thöne C, Rabe T. Wir Wollen ein Kind! Unfruchtbarkeit: Ursachen und Behandlung. Munich: dtv; 1996.

- Wile D. The Chinese Sexual Yoga Classics including Women’s Solo Meditations Texts. New York: State University of New York Press; 1992.

- Brand M von. Der Chinese in der Öffentlichkeit und der Familie, Wie er Sich Selbst Sieht und Schildert. Berlin: Reimer; ca. 1910.

___________

* Translation copyright Brigitte Dubiel, http://german.about.com/library/blgzauberl.htm, accessed April 24, 2009.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>