Fig. 6.1

These are examples of inadequate plain radiographs of a femur fracture. (a) AP radiograph; (b) lateral radiograph. As the knee joint is not included on the radiograph, a distal femur fracture could be easily missed. It is imperative that the entire bone be included in the radiographic series

Associated Injuries

Multiple injuries are commonly associated with femoral shaft fractures and include not only other musculoskeletal injuries but also systemic injuries to the chest, head, and abdomen. Clearly any other extremity can be involved, but particular care should be given to the affected leg, specifically the hip and knee joints. The most common injury around the hip is a concurrent femoral neck fracture which has been reported to occur in approximately 2.5 % of femoral diaphyseal fractures [4]. As noted it is critical to assess for a femoral neck fracture as this injury can easily be missed in both conscious and unconscious patients. However a concurrent hip dislocation, pelvic ring injuries, and acetabulum fractures can also be present depending on the mechanism of injury.

About the knee, the most commonly associated injury is a ligamentous injury, specifically injury to the PCL. This instability can be difficult to detect before the fracture is stabilized, so the knee should be thoroughly examined after fixation. Surgeons should also assess the limb for an ipsilateral tibia fracture known as a “floating knee.” These patients tend to be very seriously injured, and almost 30 % of patients with a “floating knee” have other significant musculoskeletal injuries in the same limb [5] (Fig. 6.2).

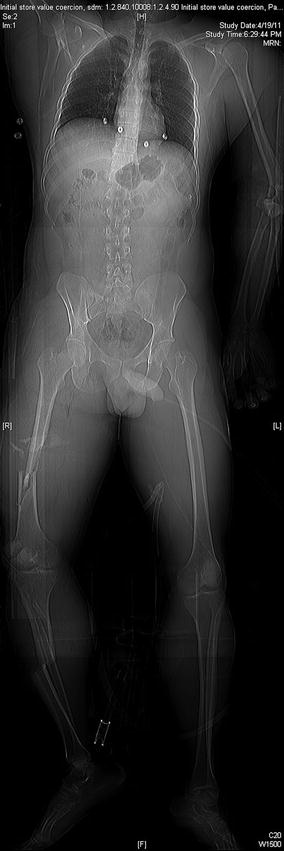

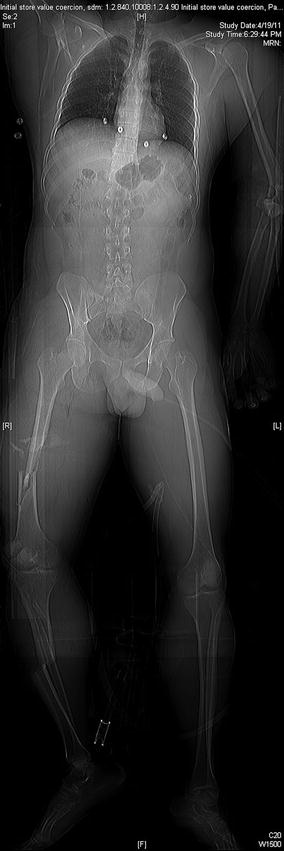

Fig. 6.2

This is a scout film from a CT scan performed on a polytrauma patient. Notice the ipsilateral femoral shaft fracture and tibia fracture or “floating knee.” Also noted on this scout film is a left elbow dislocation

The most commonly associated systemic injuries that occur in patients with femoral shaft fractures are significant head or thoracic injuries. Abdominal injuries tend to be less common and, if present, often signify a concurrent pelvic ring injury. The severity of head and chest trauma can significantly influence the manner of treatment of femoral shaft fractures, especially as it relates to timing of fixation [6]. This matter will be discussed in a later section.

Initial Management

Nonoperative management of femoral shaft fractures in adults is not appropriate except where adequate equipment, technology, and personnel are not available. Indeed, surgical stabilization is established as the standard of care for almost all femoral shaft fractures. Timing of surgical stabilization has become a more significant variable, even if definitive stabilization has to be delayed secondary to associated injuries. Stabilization should be performed as soon as the patient has been appropriately resuscitated and is felt to be stable from any concomitant systemic traumatic injuries. Some controversy exists in regard to timing of treatment in polytrauma patients with concurrent chest and/or head injuries, and this matter will be examined in a later section.

Traction

Placement of a distal femoral traction pin is a good temporizing measure and can always be considered in patients that are too unstable to go to the operating room within the first several hours after injury. This procedure can be done in the emergency department or in the ICU and will help stabilize the bone and soft tissue envelope while holding the fracture out to length prior to definitive fixation. A pin placed 3–4 cm proximal to the superior pole of the patella and midlateral to slightly anterior in the femur usually avoids an intra-articular path, which is important if the pin must be utilized more than temporarily (Fig. 6.3). Twenty-five pounds of traction is usually sufficient. The goal is not to reduce the femur fracture but to keep the limb from shortening and control the muscle spasms and further fracture instability that accompany a femoral shaft fracture. The traction pin can also be used during nailing if prepped into the field or can be removed prior to the procedure. Patients can remain in skeletal traction for as long as necessary for appropriate resuscitation and while awaiting clearance from other services. Placement of proximal tibial traction pins for femur fractures is less utilized, as traction must be pulled through a possibly injured knee joint. There have been no studies to show an increased rate of infection in femurs that were treated initially with distal femoral traction and converted to intramedullary nails.

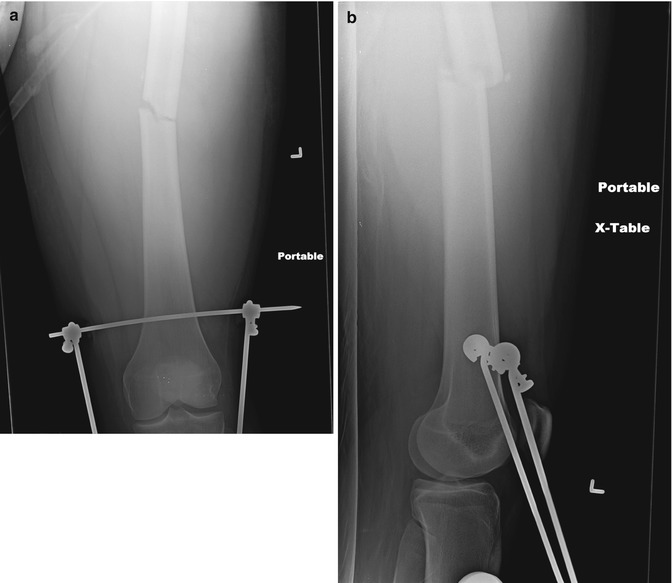

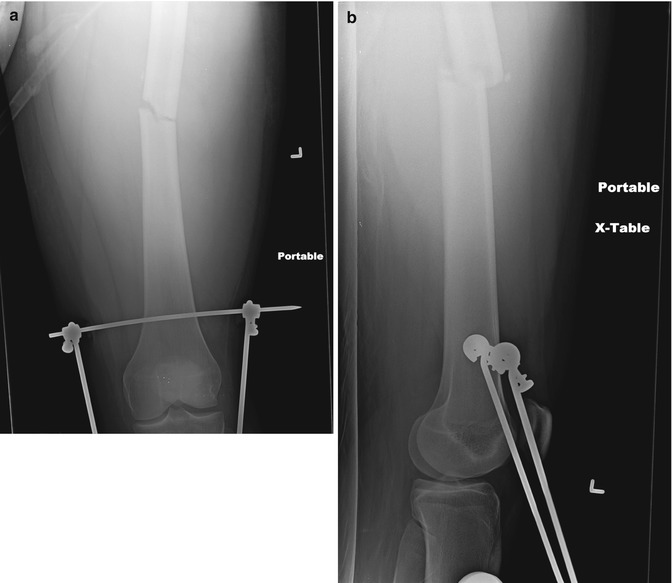

Fig. 6.3

An AP (a) and lateral (b) radiograph of the knee following placement of a distal femoral traction pin. Note the position of the pin approximately 3 cm proximal to the superior pole of the patella and slightly anterior. This pin position can facilitate nailing as a guidewire, and intramedullary nail can pass posterior to this traction pin during operative stabilization

External Fixation

Application of a uniplanar external fixator to femoral shaft fractures can be a very good temporizing step in a patient who may be too unstable for definitive operative management. The best indication for external fixation is in the polytraumatized, under-resuscitated patient already in the operating room (e.g., following an exploratory laparotomy), although it should be considered in patients with a large open, contaminated soft tissue injury or in an extremity with a vascular injury [7]. A simple external fixator should be placed with two pins proximal and two pins distal to the fracture site, typically with pins oriented from anterior to posterior or medial to lateral or somewhere in between those corridors. This quick procedure should leave the limb out to length and stable even for an extended stay in the critical care unit.

Placement of a temporizing spanning external fixator presents no barrier to definitive fixation with an intramedullary nail. Nowotarski et al. [8] examined the role of initial external fixation with early conversion to intramedullary nail in multiply injured patients. They examined 1,507 patients treated with nailing, and 59 (4 %) of those were treated with early external fixation in patients who were deemed to be critically ill and poor candidates for an immediate procedure. These patients had a mean Injury Severity Score of 29 on initial exam. All fractures were stabilized with a unilateral external fixator within the first 24 h after the injury. The average operative time was 30 min for placement of the external fixator. The average duration before a conversion to an intramedullary nail was 7 days and the infection rate was 1.7 %, which is comparable to the infection rate in immediate intramedullary nail placement. They therefore concluded that immediate external fixation followed by early closed intramedullary nailing is a safe treatment method for fractures of the shaft of the femur in selected multiply injured patients [8]. Many centers routinely perform conversion to nail up to 2–3 weeks post-injury provided no pin tract problems are evident.

Immediate fixation

Immediate definitive treatment is an option in a patient with an isolated femur fracture or in a polytrauma patient that has been sufficiently resuscitated. A stable patient will be more comfortable following stabilization of this long-bone fracture, and fixation should be done as soon as is reasonable for patient comfort as well as to lower the risk of further local and systemic injury due to the unstabilized fracture. Fixation within 24 h is generally endorsed, indicating that while emergent night work is not typically required, expeditious scheduling should be undertaken.

Treatment

Plating: Compression Versus Bridge

Indications for plate fixation of a femoral shaft fracture are limited with the advent of modern nailing techniques. However, plating can be considered in a patient with large open wounds, if the instrumentation, expertise, or imaging capability for intramedullary nailing is not available; in periprosthetic femur fractures; and in some select pediatric femur fractures. Plating can be accomplished through a subvastus lateral incision, or submuscular plating can be performed using a percutaneous technique. Wenda et al. demonstrated that closed plating techniques merely increase the difficulty of the operation without imparting any real benefit [9]. When performing a lateral incision, however, surgeons must control bleeding from the perforating vessels. Plating is not recommended for most femoral shaft fractures if interlocked intramedullary nailing is available. Also, as plating represents a load-bearing type of construct as opposed to the load-sharing construct of an intramedullary nail, patients often require protected weight bearing for 12–14 weeks, which may negate some of the anticipated benefits of early fixation and mobilization.

Compression Plating

Standard compression plating can be done in any simple fracture pattern (transverse, spiral, short oblique) through a direct lateral approach or through a traumatic wound. Anatomic reduction of the fracture in these simple patterns can be performed directly with reduction clamps. Interfragmentary lag screws should be placed if possible, and then a large fragment compression plate can be placed laterally to be used as a neutralization plate. Current recommendations suggest three to four well-spaced bicortical screws proximal and distal to the fracture site through a 10–14-hole plate to provide long, balanced fixation.

Bridge Plating

If there is a significant amount of comminution present, bridge plating can be considered. Reduction of the fracture mostly occurs indirectly in these fractures. Direct manipulation of fragments can be undertaken, but care should be taken to avoid stripping the soft tissues from any pieces. Correct length, alignment, and rotation of the femur must be restored. Longer plates are typically required and should ideally have a bow in order to restore the patient’s normal anatomic femoral bow. Comparison radiographs of the uninjured leg can be a helpful adjunct in significantly comminuted fractures or in open fractures with a significant amount of bone loss. One can also consider prepping the nonoperative limb into the operative field for direct comparison.

Percutaneous bridge plating is also an option. A small incision is made through the tensor fascia lata at the level of the epicondyle distally, and a counter incision is made laterally at the level of the vastus ridge. The plate can then be slid submuscularly in a retrograde fashion. Typically the plate is then attached to the bone with a single bicortical screw at one of the incisions, and the leg is then manipulated to gain a reduction prior to fixation through the opposite incision. Care must be taken as mentioned above to assure that the correct length, alignment, and rotation has been accomplished prior to fixation. Additional screws can then be placed percutaneously into the plate with the goal of four well-spaced bicortical screws on both sides of the fracture site.

Intramedullary Nail

Where available, reamed, locked, intramedullary nailing represents the standard of care for femoral diaphyseal fractures. Outcomes following treatment of femoral diaphyseal fractures with intramedullary nailing are excellent, and the complications are minimal. Non-reamed nails have been associated with a higher incidence of nonunion and hardware failure and should not be used. In addition to benefitting union rates, limited reaming does not increase the incidence of malunion, infection, pulmonary embolism, or compartment syndrome [10].

Antegrade Nailing

Most femoral diaphyseal fractures can be managed with an antegrade femoral nail, and antegrade nailing is the preferred method of treatment of these authors. Common positioning strategies include supine on the fracture table with the limb in a traction boot or skeletal traction, supine on a radiolucent table with a large bump underneath the patient’s injured hip and the entire limb draped free into the field, or lateral either on a traction table or with the limb draped free. Each position has its advantages and disadvantages. Use of a fracture table may be helpful when a surgeon does not have any assistants as the fracture position is maintained by the traction (Fig. 6.4). The fracture tends to sag on the fracture table, however, and reaching the piriformis fossa can sometimes be a challenge, especially in obese patients. The supine position on a radiolucent table is preferentially employed at many centers where ample help available. Setup time is minimal. The limb can be manipulated during the procedure to assist in obtaining an appropriate starting point in the piriformis fossa or greater trochanter, depending on the type of nail selected. Assistants are necessary to manipulate the limb, or a distal femoral or proximal tibial traction pin may be placed to facilitate regaining length and achieving reduction (Figs. 6.5 and 6.6). Finally, the lateral position is extremely useful when nailing morbidly obese patients in an antegrade fashion, but setup time can be quite extensive. This position provides easier access to the piriformis or trochanteric starting point. It can also be advantageous in very proximal femoral shaft fractures in order to counteract the usual flexion deformity in these types of fractures. However, fluoroscopic visualization of the proximal femur is difficult in the lateral position, and care must be taken to avoid allowing the distal fragment to drift into valgus because of gravity.

Fig. 6.4

This is a demonstration of positioning a patient supine on a fracture table for intramedullary nailing of a right femur fracture. (a) Positioning with both legs into traction boots and the arm on the affected side brought across the body to facilitate nailing. (b) Note that the non-affected limb is also placed in a traction boot and dropped down to facilitate fluoroscopic evaluation of the affected limb. The nonoperative limb can also be placed into a well-leg holder if the surgeon prefers. (c) The patient from the end of the table, with the well leg dropped out of the operative field. It should be noted that with this technique, the femur fracture tends to sag on the fracture table; this deforming force will have to be overcome in order to reduce the fracture. A crutch placed under the drapes can be useful to help counteract this sag

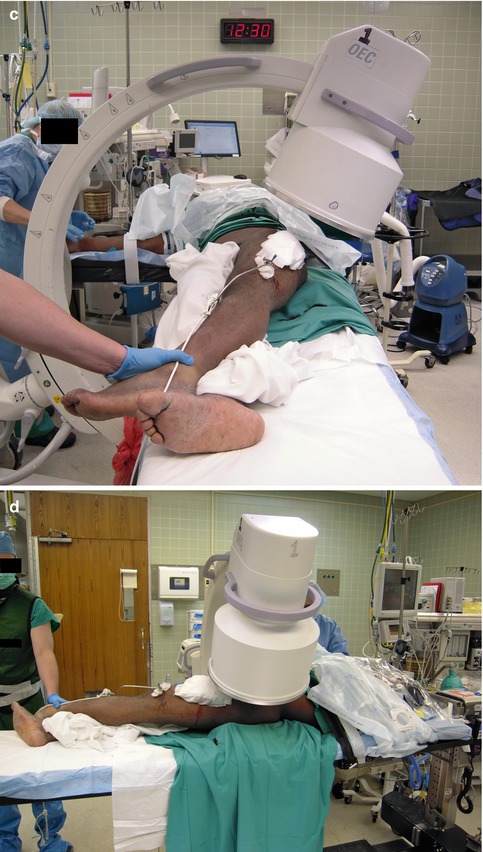

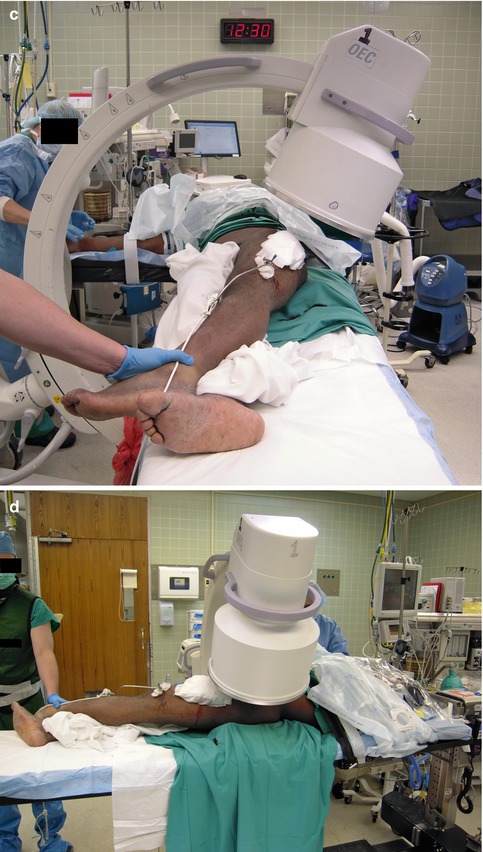

Fig. 6.5

An example of the positioning of a patient with a left femur fracture supine on a radiolucent table. The patient had a previously placed distal femoral traction pin during prolonged resuscitation following multiple gunshot wounds. (a) The bump placed under the fractured limb, allowing easier access to the piriform fossa. (b, c) Position of the image intensifier for obtaining an AP radiograph. (d, e) Position of the image intensifier for obtaining a lateral radiograph of the proximal femur. Occasionally the limb has to be manipulated from the foot in order to obtain a good lateral radiograph. The traction pin may also be removed prior to the procedure or prepped into the field with use of a sterile traction bow and sterile rope. If this is to be utilized, the traction should be taken off the opposite side of the distal end of the table, pulling traction medially and adducting the limb

Fig. 6.6

An example of placement of a guidewire with the patient in a supine position. In a thin patient, this can be done with relative ease in this position

As noted, modern nail instrumentation allows the surgeon to choose nails designed to be inserted either through the piriformis fossa in line with the canal or through the greater trochanter slightly lateral to the femoral canal. No compelling data demonstrate superiority of one approach over the other. Both nail types contain an anterior bow, and the trochanteric nails also have a lateral bend proximally to account for the off-axis starting point. Modern straight femoral nails should not be placed through a greater trochanteric insertion point because the femoral neck is at risk of being damaged by the stiff nail, and this tends to malreduce the fracture. Similarly, one must be very meticulous with reduction of the fracture when using trochanteric start nails to assure that the implant does not force the femur into varus upon insertion.

It is also critical to ream the canal with the fracture site well reduced. Fluoroscopy should be used during reaming to assure that the canal is not eccentrically reamed at the fracture site. Passage of the nail will facilitate improved alignment when the fracture is in the isthmus, the narrowest portion of the femoral diaphysis. However, if the fracture is proximal or distal to the isthmus and the canal eccentrically reamed, reduction may not be affected by nail passage. Most sources now recommend a ream to fit approach, and most manufacturers recommend over-reaming 1 mm larger than the selected nail size. In straightforward diaphyseal femur fractures, a smaller nail (typically an 11 or 12 mm nail) is sufficient in most adult femur fractures.

Retrograde Nailing

Multiple established indications for retrograde femoral nailing include but are not limited to ipsilateral femoral neck fractures identified prior to nailing, ipsilateral tibia fracture (“floating knee” injuries), ipsilateral acetabulum fractures, bilateral femur fractures, morbid obesity, and pregnancy. Some centers preferentially treat virtually all femoral shaft fractures with a retrograde reamed nailing technique, citing ease of positioning, relative rapidity of the procedure, and equivalent functional results as support. As in antegrade nailing, the starting point is critical in retrograde nailing and must be in line with the somewhat more distant canal to avoid creating angular malalignment. The knee joint and proximal femur must both be adequately visualized using fluoroscopy. The nail is inserted through an entry point in the knee joint at the level of Blumensaat’s line on the lateral view and just anterior to the posterior cruciate ligament fibers.

Controversies

Multiply Injured Patient/Damage Control

The dogma of early total orthopedic care for multiply injured patients has undergone a dramatic shift over the last decade. With the advent of widespread ATLS protocols and critical care advances, more patients are surviving injury constellations that were frequently fatal in the past. Critical care and orthopedic surgeons, in response to evidence supportive of appropriate, targeted early intervention for the most seriously injured patients, have adapted their practices to incorporate damage control measures when early total care is not appropriate. This practice involves early often temporary stabilization of injuries via brief procedures with limited blood loss in order to assist in the resuscitation of multiply injured patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree