Femoral Shaft Fractures: Retrograde Nailing

Robert F. Ostrum

Eric D. Farrell

Retrograde femoral intramedullary nailing has become an accepted method of treatment for femoral shaft fractures, especially those associated with other injuries. Early attempts at retrograde nailing with entry portals through the medial femoral condyle led to comminution and malunion. Moving the starting point to a centromedullary position produced better results with fewer complications. Prior to the introduction of locked plates, internal fixation of comminuted, supracondylar femur fractures was associated with a relatively high incidence of malunion, nonunion, hardware failure, and loss of knee motion. For this reason, a retrograde locking nail was developed. Originally designed as a short nail for distal femur fractures, full-length nails were ultimately developed to manage diaphyseal injuries.

Current indications include diaphyseal femoral-shaft fractures at least 5 cm below the bottom of the lesser trochanter down to the supracondylar femur including fractures with an intercondylar split. Associated musculoskeletal injuries often favor retrograde over antegrade femoral nailing. The ability to do a retrograde nailing in a patient with an ipsilateral acetabulum fracture, which might require a posterior approach, allows for the femoral shaft to be treated and for a pristine area around the posterior trochanter for fixation of the acetabulum fracture.

Ipsilateral fractures of the femur and knee can often be managed through a single, small incision with placement of a retrograde femoral nail and an antegrade tibial nail. In multiply injured patients with other ipsilateral or contralateral lower-extremity fractures, supine retrograde nailing on a radiolucent table allows either simultaneous or sequential fixation of other fractures, saving valuable operating time.

Bilateral femoral-shaft fractures are excellent candidates for retrograde nailing. One of the best indications for a retrograde nail is an ipsilateral hip and shaft fracture. Most authors recommend independent fixation of both injuries with cannulated screws or a sliding hip screw proximally followed by a retrograde nail for the shaft fracture. This approach allows for the best possible treatment of each fracture without compromising fixation of either one.

Relative indications for retrograde nailing include femoral shaft fracture in the obese or very muscular patient or in patients with trochanter lipodystrophy where antegrade nailing may be difficult. Polytraumatized patients often benefit from rapid positioning on a

radiolucent table and freeing the area around the pelvis and abdomen for simultaneous treatment by other surgical disciplines. Although antegrade nailing techniques can be done on a radiolucent table rather than a fracture table, it is still more cumbersome than a retrograde approach. The supine position allows for more physiologic treatment of the lungs and brain in a seriously injured patient being resuscitated.

radiolucent table and freeing the area around the pelvis and abdomen for simultaneous treatment by other surgical disciplines. Although antegrade nailing techniques can be done on a radiolucent table rather than a fracture table, it is still more cumbersome than a retrograde approach. The supine position allows for more physiologic treatment of the lungs and brain in a seriously injured patient being resuscitated.

Contraindications to retrograde nailing include patients with open growth plates; previous anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; or preexisting hardware or prosthesis that would block a retrograde insertion technique. The use of a retrograde nail in complex, grades IIIA and IIIB, open femur fractures is controversial due to the risk of contamination and subsequent infection in the knee joint. Other treatment modalities, such as bridging external fixation, may be more appropriate.

Preoperative Planning

A detailed history and physical examination of the patient should be performed. Many patients with femur fractures have serious associated limb or life-threatening injuries. The condition of the soft tissues and limb compartments, as well as the neurovascular status should be clearly documented.

Full-length radiographs of the entire femur are necessary. Dedicated radiographs of the knee and hip are needed to rule out intercondylar extension or ipsilateral femoral-neck fractures. Displaced intra-articular fractures are often obvious; however, traction views or fluoroscopic radiographs in the operating room may be helpful in identifying subtle injuries to the knee joint. Full-length films also allow determination of the length and diameter of the intramedullary canal. Small women, persons of Asian descent, and those with developmental problems often have very narrow canals. Most manufacturers do not make retrograde nails smaller than 9 or 10 mm in diameter. This must be recognized prior to surgery so that either a nail of appropriate diameter is available or other surgical options are considered. Many studies have shown that the best results following retrograde femoral nailing are achieved with full-length nails inserted to the lesser trochanter. The surgeon should be certain that a full complement of nails is available at the time of surgery.

The decision to use a percutaneous or limited open approach for nail insertion may be dependent on several factors. The presence of an intra-articular split in the femoral condyles should be a priority concern when planning the approach. Visualization and fixation may be compromised by an ill-placed incision. Cannulated screws of similar metallurgy to the retrograde nail should be available, as well as a sliding hip screw for associated hip fractures. When planning for treatment of an ipsilateral femoral-neck fracture, important decisions must be made prior to surgery about the table and patient position during this combined surgical technique. For patients with multiple fractures, as well as a femoral shaft fracture, proper positioning of all involved extremities and adequate prepping and draping can all be done prior to the initiation of surgery if preoperative planning is performed.

Surgery: Patient Positioning, Technique, and Results

Nailing is usually performed under general anesthesia, but in isolated injuries in the elderly, a spinal may be utilized. Retrograde intramedullary femoral nailing is performed with the patient supine on a radiolucent table. Some authors prefer a bolster under the torso, but we believe that this can interfere with the determination of appropriate femoral rotation. With few exceptions, we favor a straight supine position and anterior positioning of the patella. The limb is sterilely prepped and draped from the toes to the iliac crest. It is important to have the entire leg exposed to allow for evaluation of length and rotation, as well as placement of proximal anterior-posterior locking screws.

Knee flexion between 40 and 60 degrees is a key part of the case. Too little knee flexion does not allow for correct position of the guide pin or passage of the reamers and nail, which can impinge on the tibial plateau. Too much flexion can cause the patella to obscure

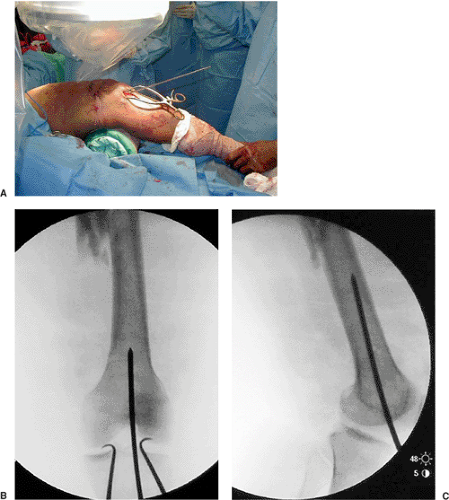

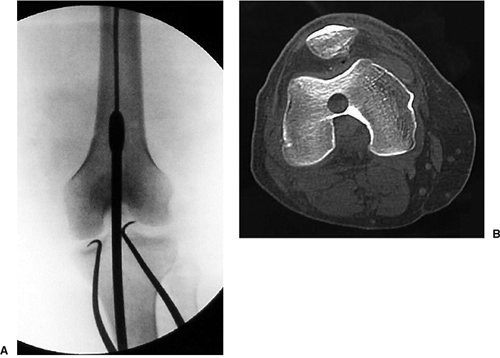

the distal-femoral entry site and leads to excessive shortening in comminuted fractures. Appropriate flexion can be maintained with a radiolucent triangle or sheets used as bolsters with the leg maintained in neutral rotation. For the percutaneous approach, a 2- to 3-cm incision is made just medial to the patellar tendon. Alternatively, a patellar tendon splitting approach can be used. Our preference is medial to the tendon because the incidence of anterior knee pain appears to be less with this approach. The fat pad and synovium are bluntly dissected from the intercondylar region by spreading with a scissors. The intercondylar notch is either visualized through a larger incision or palpated through the percutaneous incision. Anterior-posterior fluoroscopy is used, and a trochar-tipped guide pin is positioned in the center of the notch. Rotation of the fluoroscopy unit to a lateral view needs to confirm that the guide pin is centered just at the tip of the inverted V formed by Blumensaat’s line. The guide pin is then inserted 4 to 5 cm into the distal femoral metaphysis, with the surgeon making sure that it is centered in both projections (Fig. 22.1). The entry portal is created with the use of a cannulated 12- or 13-mm straight reamer while the patellar tendon is protected with retractors or a sleeve. The guide pin is then removed (Fig. 22.2).

the distal-femoral entry site and leads to excessive shortening in comminuted fractures. Appropriate flexion can be maintained with a radiolucent triangle or sheets used as bolsters with the leg maintained in neutral rotation. For the percutaneous approach, a 2- to 3-cm incision is made just medial to the patellar tendon. Alternatively, a patellar tendon splitting approach can be used. Our preference is medial to the tendon because the incidence of anterior knee pain appears to be less with this approach. The fat pad and synovium are bluntly dissected from the intercondylar region by spreading with a scissors. The intercondylar notch is either visualized through a larger incision or palpated through the percutaneous incision. Anterior-posterior fluoroscopy is used, and a trochar-tipped guide pin is positioned in the center of the notch. Rotation of the fluoroscopy unit to a lateral view needs to confirm that the guide pin is centered just at the tip of the inverted V formed by Blumensaat’s line. The guide pin is then inserted 4 to 5 cm into the distal femoral metaphysis, with the surgeon making sure that it is centered in both projections (Fig. 22.1). The entry portal is created with the use of a cannulated 12- or 13-mm straight reamer while the patellar tendon is protected with retractors or a sleeve. The guide pin is then removed (Fig. 22.2).