Features of Osteoarthritis at Specific Sites

Features of osteoarthritis of the knee

The knee is comprised of one synovial cavity with three principle compartments: the medial and lateral tibiofemoral joints, and the patellofemoral joint. Any or all of these compartments may be affected by osteoarthritis, although different patterns of involvement occur and may be associated with different epidemiological risk factors.

Since the knee is a large and relatively superficial joint, the signs of osteoarthritis can be easily appreciated clinically. Modest synovitis results in local warmth and joint effusion. Small effusions tend to fill in the sulci on the medial and lateral aspects of patellae. Larger effusions tend to open up the large suprapatellar pouch, presenting a swelling above and to either side of the patella.

There is a natural weak point in the posterior aspect of the knee capsule, and with any synovial effusion there is a potential for a cyst-like protrusion to form known as a ‘popliteal’ or Baker’s cyst (4.1). This may cause localized posterior pain, and may expand into the calf as a calf cyst.

Course crepitus is a common feature of osteoarthritis, and is readily appreciated by holding the front of the knee as it moves. It probably reflects fibrillation of the articular cartilage, or eventually bone rubbing on bone, and hence friction on movement. Bony swelling, i.e. osteophyte, can be palpated and often seen, particularly on the medial and lateral aspects of the knee.

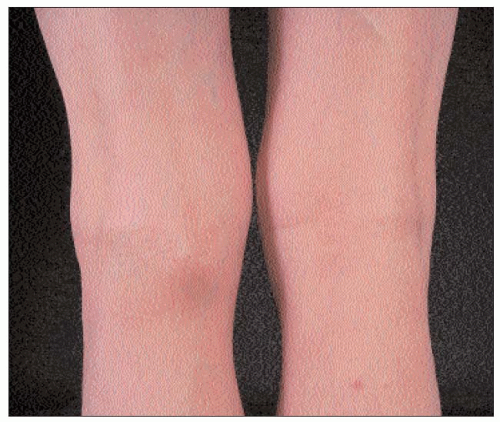

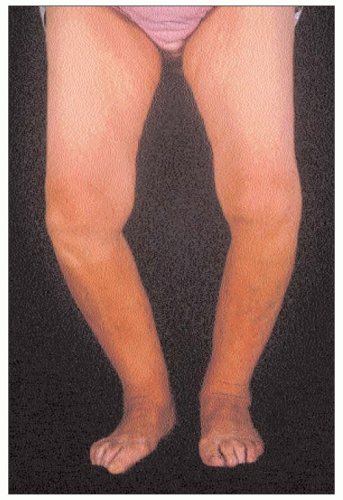

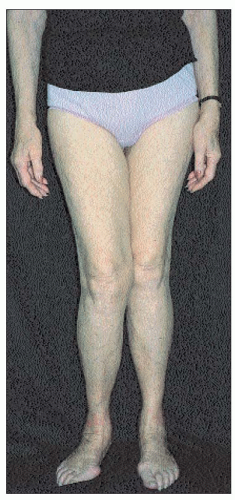

Varus (4.2) and valgus (4.3) deformities should be assessed standing, since they are then maximized. Varus is the more common since osteoarthritis targets the medial more than the lateral tibiofemoral compartment. Fixed flexion deformity is also common. It may be obvious with the patient standing, but mild degrees are best assessed with the patient lying down and pushing both knees backwards onto the couch. This manoeuvre also allows detection of quadriceps wasting, which is common and often exaggerated by the extent of the bony swelling.

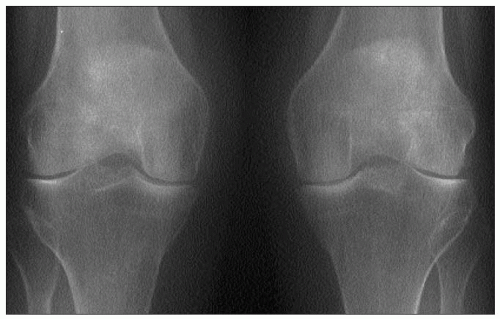

4.2 Severe bilateral varus deformity, with accompanying fixed flexion, in an elderly woman with knee osteoarthritis. |

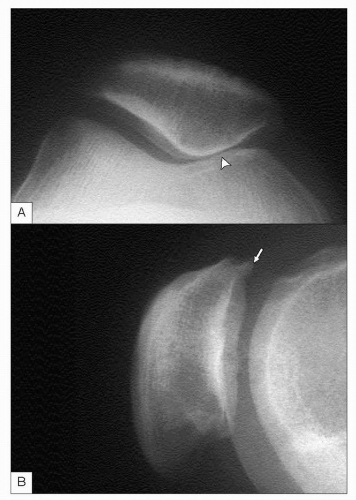

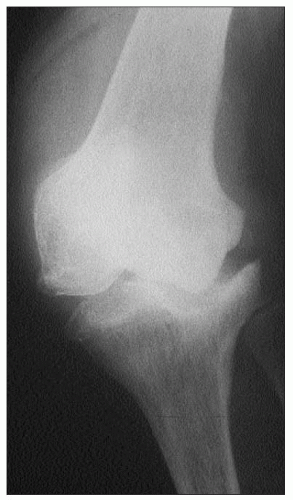

The pattern of compartmental involvement has, for many years, been masked by the limited extent to which structural involvement was determined by radiology. Many early studies employed only a single anteroposterior, non-weightbearing view which often underestimates the degree of tibiofemoral involvement and completely ignores the patellofemoral joint. It is now recognized that loading the tibiofemoral compartment, by taking the radiograph with the patient standing, allows a better estimate of the intercortical distance. Furthermore, a semi-flexed position brings the maximally affected cartilage into the weight-bearing position and increases the sensitivity of detecting tibiofemoral narrowing. It is now recognized that the patellofemoral compartment is commonly affected by osteoarthritis and indeed is a common cause of anterior knee pain. Osteophyte can be readily recognized using most standard radiographic techniques, but joint space narrowing is best appreciated using an axial view (4.4).

4.3 Gross right valgus and mild left varus deformity in a patient with osteoarthritis. This asymmetrical combination is sometimes called ‘windswept’ or ‘skier’s’ knees. |

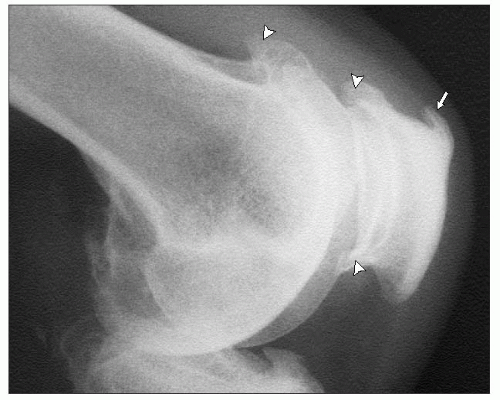

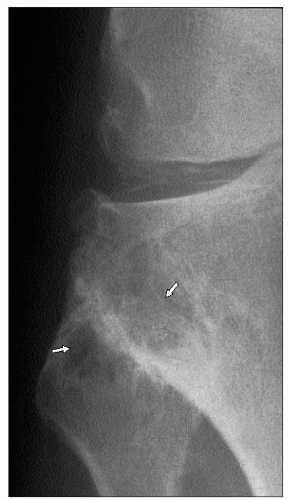

Using sensitive imaging techniques, it is apparent that most cases of knee osteoarthritis involve all three compartments to some extent, but cartilage narrowing usually predominates in just one or two compartments. Osteophytes are often more widespread at many sites within the knee, and tend to show characteristic directions of growth. For example, in the medial tibiofemoral compartment, they tend to grow horizontally and then away from the joint line (4.5); whereas in the lateral tibiofemoral compartment, the femoral osteophyte grows proximally away from the joint line, but the tibial osteophyte often grows vertically towards the femur (4.6). In the patellofemoral compartment, lateral subluxation is common (readily seen on the skyline view) and osteophyte tends to grow laterally, hugging the femoral contour (4.7). Lateral views show osteophyte superiorly and inferiorly, and often enthesophyte at the quadriceps and patella tendon insertion sites (4.8). Presumably, these differences in osteophyte direction are driven by biomechanical forces. Surgical removal of tibiofemoral osteophytes has been shown to increase joint movement, so the osteophytes appear to be a stabilizing factor that help splint the osteoarthritic joint as it loses cartilage and remodels its shape.

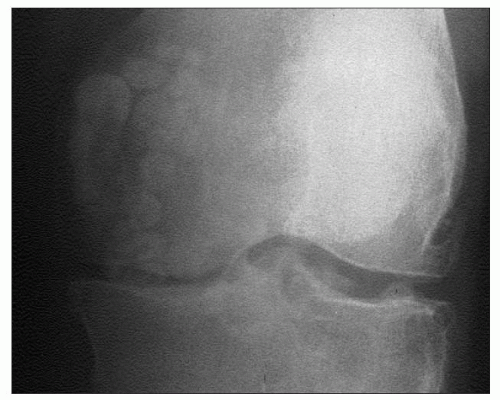

Osteochondral bodies are not infrequent within the capsule and ligaments of the joints (4.9), and may relate to locking, if close to the joint line. Chondrocalcinosis is readily appreciated in the knee, and 80% of cases of chondrocalcinosis are apparent on anteroposterior radiographs. Calcification occurs in the fibro- and hyaline cartilage and may also be apparent in the capsule of the joint (4.10).

Predominant medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis appears to be particularly common in men. Associated meniscal degeneration is usually a feature, and is more often appreciated if other imaging modalities (such as MRI) are used. Varus deformity, often with fixed flexion if severe, is the most common deformity in men with knee osteoarthritis. Varus deformity is a risk factor for more rapid X-ray progression.

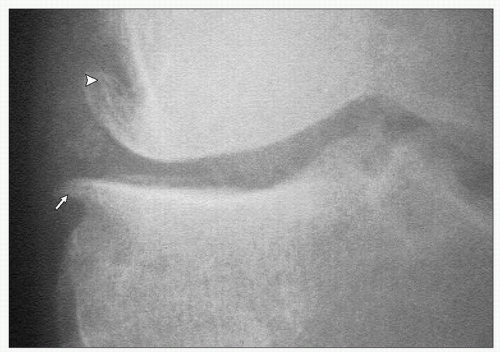

4.5 Medial tibiofemoral osteophytes, growing horizontally (arrow) or away (arrowhead) from each other. |

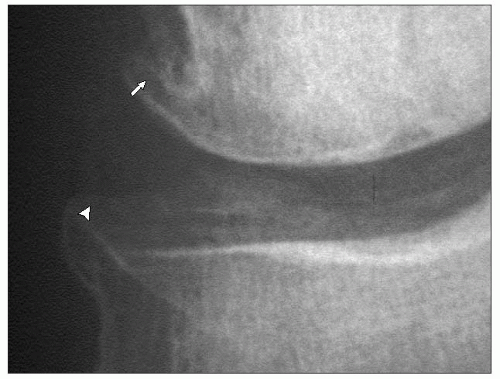

4.6 Lateral tibiofemoral osteophyte. The femoral osteophyte (arrow) is growing proximally away from the joint, but the tibial osteophye (arrowhead) can be seen coming upwards towards the joint. |

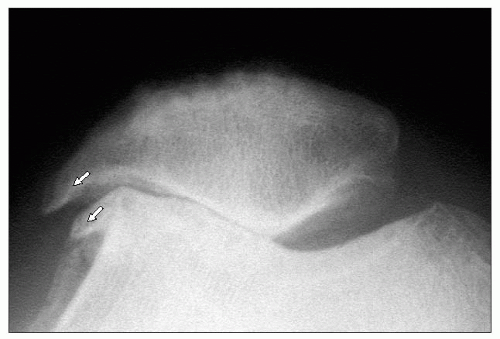

4.7 Skyline view showing marked lateral narrowing, lateral patella subluxation, and osteophytes on both the femoral and patella aspects (arrows), following a similar direction of growth. |

4.10 Knee radiograph showing medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis and chondrocalcinosis of fibrocartilage and hyaline cartilage (‘pyrophosphate arthropathy’). |

Predominant patellofemoral osteoarthritis is also common, particularly in women. Since the patella is intimately involved in the quadriceps mechanism, muscle wasting and disability appear to be a prominent feature of patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Characteristics of patellofemoral pain include well-localized anterior knee pain, particularly bad when going up or down stairs or an incline, and progressive aching anteriorly when sitting, relieved by getting up and ‘stretching the legs.’

The third most common pattern is a combination of both patellofemoral and medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis. The more knee compartments involved, and the more severe the structural changes, the more likely it is to detect calcium pyrophosphate or apatite crystals in aspirated knee synovial fluid.

Isolated lateral tibiofemoral osteoarthritis is a very uncommon pattern. However, pathological involvement is often present, and it may be that the natural varus deformity (common in medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis) tends to open up the lateral tibiofemoral joint. If this is the case, cartilage loss in this compartment is not readily appreciated radiographically. Predominant involvement of the lateral tibiofemoral joint may be associated with preceding trauma, previous lateral meniscectomy, or apatite-associated destructive arthritis (4.11). A valgus deformity is the usual consequence of severe involvement.

In contrast to osteoarthritis, chronic inflammatory synovitis, such as occurs with rheumatoid arthritis, usually results in a diffuse tricompartmental pattern of joint space loss and little, if any, bone response (4.12).

The superior tibiofibular joint is the final joint of the knee. Although radiographic osteoarthritis and often marked cystic change (4.13) can occur at this joint, it is rarely a cause of symptoms. Cystic change at this site is more common in patients with knee chondrocalcinosis.

4.12 Knee radiographs of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis showing diffuse joint space narrowing with osteopenia, and without osteophyte or sclerosis. |

Features of osteoarthritis of the hip

Osteoarthritis of the hip is a common clinical problem, and is responsible for a great deal of pain and suffering, as well as being the main indication for hip arthroplasty. Unlike osteoarthritis elsewhere, it shows an overall equal sex distribution, but it predominates in younger men (preretirement age) and in elderly women. The principle clinical feature is pain. This is usually felt anteriorly, deep in the groin. It may, however, radiate widely and can be felt in the anteromedial thigh, buttock or the anteromedial aspect of the knee, and may extend as far as the ankle. It can present as knee pain alone, and this may lead to clinical confusion until the knee and hip are both examined.

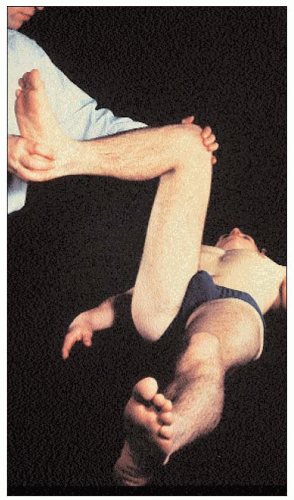

4.14 Internal rotation with the hip in flexion. This is first movement to become painful and restricted with hip arthropathy, and is the most sensitive clinical test for early hip osteoarthritis. |

4.15 Right hip osteoarthritis in a 59-year-old man, showing the typical deformity of hip flexion (with compensatory knee flexion) and external rotation. |

4.16 Advanced right hip osteoarthritis in an elderly woman, showing typical late deformity of hip (and knee) flexion, external rotation, and adduction at the hip. |

Restriction of movement commonly occurs and may be relatively painless. The restriction initially affects internal rotation of the hip, particularly in flexion (4.14). Later a flexion deformity of the hip occurs, and the patient may walk with a flexed knee to compensate and a degree of equinus. Leg length shortening, due to both the flexion deformity and possibly loss of joint space, can result in a compensatory scoliosis. At an even later stage, a fixed adduction and external rotation of the hip can occur (4.15, 4.16).

Muscle wasting is not readily appreciated at the hip, especially in elderly patients, although gluteal and quadriceps wasting is often present. Acute synovitis can occur, including pseudogout, but appears to be unusual in clinical practice. Functional limitation is often a major problem through interference with daily activities, such as putting on socks, getting in and out of cars, and walking.

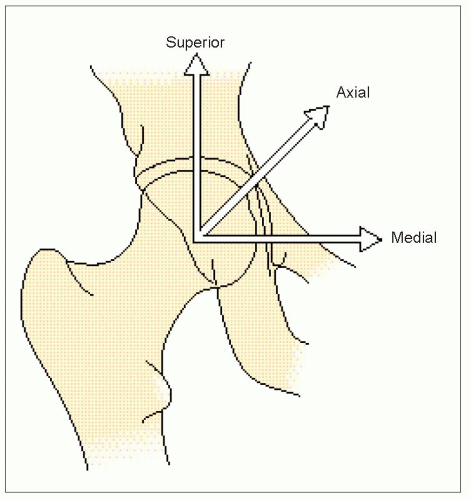

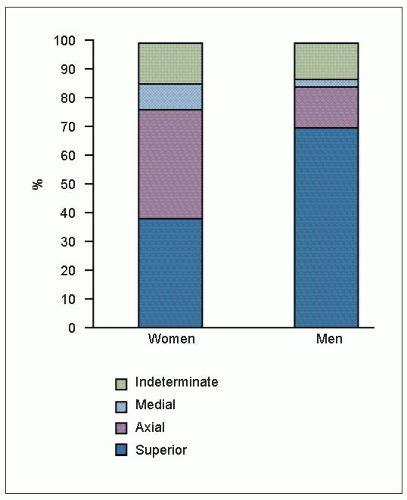

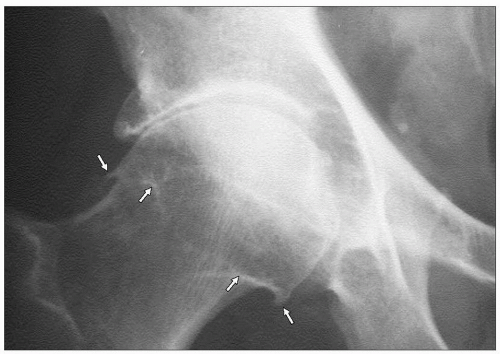

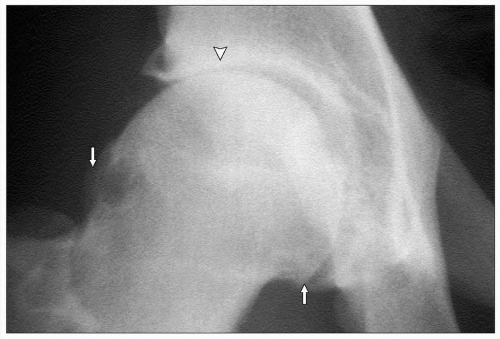

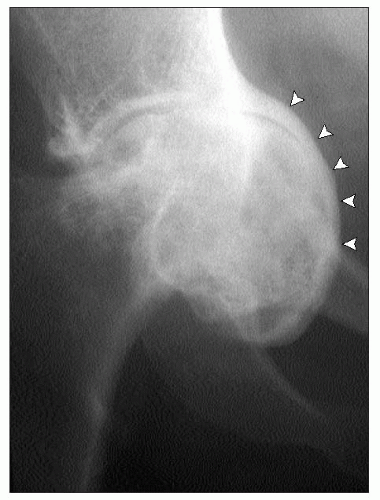

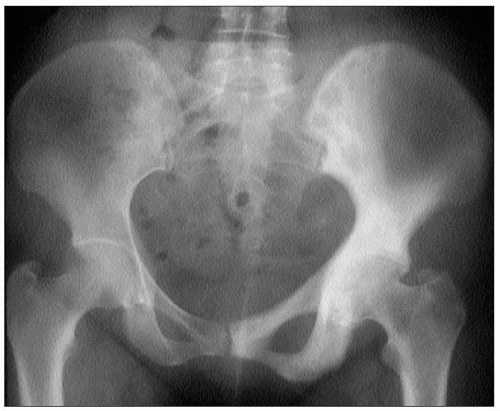

Radiographically, osteoarthritis of the hip tends to be a focal disease with regard to joint space loss. Superiornarrowing is the most common pattern, especially in men, though focal-narrowing may also be axial or medial (4.17). The superior pattern may be predominantly superolateral (4.18), and associate eventually with upwards and outwards subluxation of the femoral head, or superomedial. The medial (4.19) or axial patterns are less common (4.20), but an axial pattern, in particular, may result in a protrusio acetabulae abnormality (4.21).

4.18 Superolateral narrowing in hip osteoarthritis. There is also osteophyte on the femoral head (arrows), and sclerosis at the site of maximal narrowing (arrowhead). |

4.21 Protrusio acetabulae abnormality – the femoral head has migrated axially, narrowing the acetabular bone and pushing it inwards into the pelvis (arrowheads). |

Sometimes, especially with late, marked osteoarthritis, a discrete pattern is hard to discern (an ‘indeterminate’ pattern). A uniform concentric pattern of cartilage loss is very rare and, especially if there is paucity of accompanying osteophyte, should always suggest an underlying inflammatory or metabolic disease.

Unless there is a specific localizing factor in operation, such as prior trauma, the pattern of involvement is usually identical if osteoarthritis affects both hips.

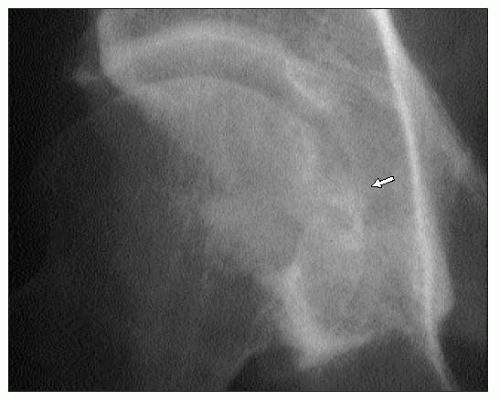

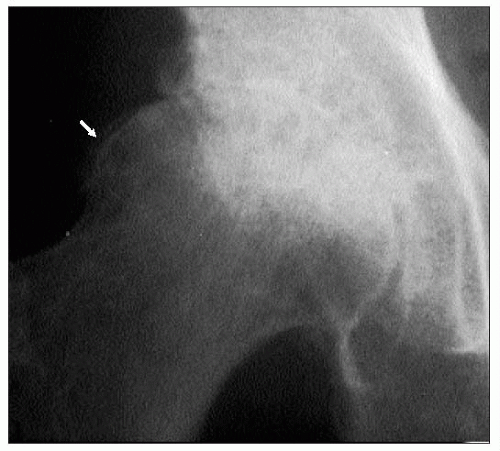

Osteophyte occurs at specific locations which can include the acetabular margin, and the site of capsular insertion on the femur where it may appear as a line across the femoral head, which is in reality a two-dimensional view of a ring of osteophyte (4.22). Cortical buttressing may occur, as well as trabecular thickening. The latter tends to occur parallel to the forces acting on the femoral neck, and thus buttress the medial aspect of the femoral neck. Chondrocalcinosis may be seen occasionally in the hyaline cartilage of the femur (4.23), and in the acetabular labrum, though it is more prevalent in the symphysis pubis (4.24). Osteochondral bodies may be seen around the joint, with some appearing to form as extensions to acetabular osteophyte.

Cyst formation can occur in the acetabulum, and is particularly common in patients with pyrophosphate arthropathy, especially in association with haemochromatosis (4.25). Avascular necrosis of the femoral head can sometimes be appreciated as a focal-marked loss of bone stock.

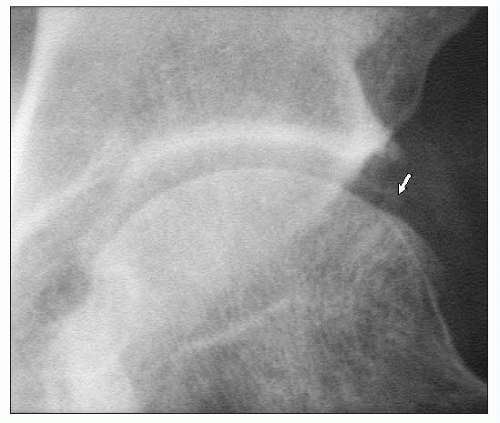

4.23 Hip chondrocalcinosis affecting the femoral head hyaline cartilage, just visible superolaterally (arrow). |

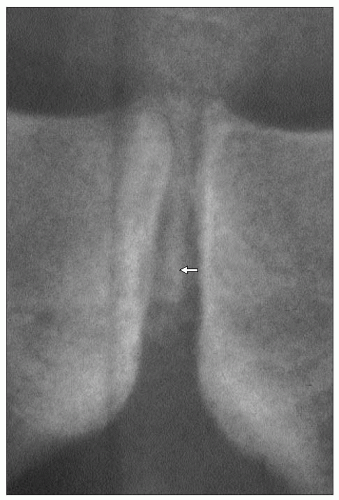

4.24 Chondrocalcinosis (arrow) of the symphysis pubis (the most common site for chondrocalcinosis in the pelvis). |

There has been discussion as to how much dysplasia might predispose to osteoarthritis. It appears to be an unusual cause of sporadic osteoarthritis, but occasionally patients presenting with osteoarthritis show clear evidence of acetabular dysplasia, or even possible congenital dislocation of the hip. Prior trauma leading to leg length shortening or malalignment may be appreciated. All these factors have been implicated in determining speed of progression in hip osteoarthritis, but recent meta-analyses suggest that only some of these may be important (Table 4.1).

Paget’s disease is common in the pelvis, and may affect the acetabulum with resultant hip osteoarthritis, often with diffuse joint space narrowing (4.26).

4.26 Paget’s disease affecting the left hemipelvis and resulting in osteoarthritis. Note the diffuse, rather than focal narrowing at the hip. |

Table 4.1 Hip osteoarthritis: factors associated with progression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Features of osteoarthritis of the hand and wrist

All joints of the hand and wrist can potentially be affected by osteoarthritis (4.27, 4.28), although certain patterns of involvement are characteristic. Distal interphalangeal joint involvement is particularly common, often as part of generalized nodal osteoarthritis. Clinically, this usually starts with development of painful Heberden’s nodes around the time of the menopause. These often appear cystic or soft in the early stages of development (4.29) and occur at the superolateral aspects of the joint. Once established, the two superolateral swellings either side of the extensor tendon may fuse to form a hard bony posterior bar (4.30). Nail dystrophy with ridging (‘Heberden’s nodes nails’) is an occasional associated feature (4.29). Varying degrees of inflammation can be appreciated while the nodes evolve to their final form. The onset tends to be stuttering with sequential involvement of new joints, often in a symmetrical fashion, with earlier involvement of the dominant hand.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree