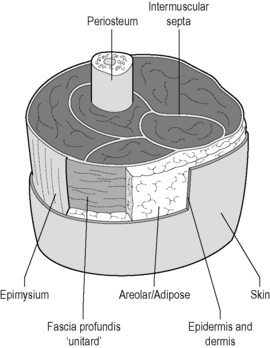

6.2 Fascial palpation The fascial system has been described as an ‘endless web,’ that is, far more organized than was previously imagined (Schultz & Feitis 1996). Fascia surrounds the entire body just under the skin as the superficial fascia, and enwraps all the other tissues and organs of the body as the deep fascia. It is, as observed by Ida P. Rolf, PhD, the “organ of form” (Rolf 1977). But in addition to its anatomical and physical properties, the fascial system is increasingly recognized for its physiologic properties (Langevin et al. 2004, 2006). While the hand is probably the primary palpatory tool, manual therapists will occasionally use more than just the palms of the hands and fingers for this purpose, with knuckles, fists, forearms, elbows, and sometimes even involving tools (See Chapter 7.14) being employed. • First, the organization of the thoracolumbar fascia, where the superficial posterior layer has a significantly different directionality than the deeper layer. In turn, the middle layer has a significantly different thickness and organization than the first two. Obviously, this speaks to their different functional roles, and knowledge of the anatomy can influence the treatment plan. • The second example involves the muscles of the posterior neck. This extraordinarily complex group has the all-important function of aligning the head such that the eyes are parallel to the horizon. At least a dozen muscles or muscle groups are present on each side of the midline. As the hands and fingers palpate from superficial to deep, different fiber directions will be encountered as well as different levels of muscle tone. Fig. 6.2.1 • Typical fascial layering, seen here as in the thigh. Other areas contain more or fewer layers between skin and bone. From Chaitow, 2010, with permission. Just deep to the superficial fascia is the deep fascia, which forms the “endless web” described by Schultz and Feitis (1996). It surrounds and supports muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and organs. • the relative weakness or tightness in muscles • the amount of induration, edema or fibrosis in soft tissues • the feel, densitiy and mobility of palpable fascial structures • identification of regions in which reflex activity is operating • possible differences in the quality of perceived tissue vitality (flaccid, toned, etc) • variations in regions of the body Philip Greenman (1989), in his book Principles of Manual Medicine, summarizes the five objectives of palpation. He suggests that the practitioner/therapist should be able to: 1. detect abnormal tissue texture 2. evaluate symmetry in the position of structures, both physically and visually 3. detect and assess variations in range and quality of movement during the range, as well as the quality of the end of the range of any movement 4. sense the position in space of yourself and the person being palpated 5. detect and evaluate change in the palpated findings, whether these are improving or worsening as time passes.

Palpation tools

What is being palpated?

Layers (see Figure 6.2.1)

Palpating for information

Palpation objectives

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine