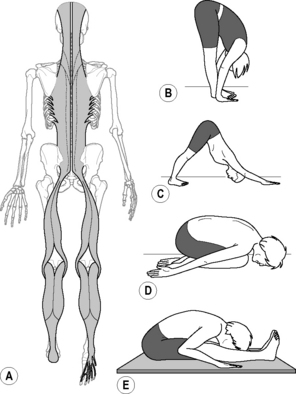

7.21 Fascia in yoga therapeutics Yoga (yoke, union, the balancing of opposites) is a form of somatopsychic self-training whose origins in the mists of prehistory are meshed with the related field of martial arts (Feuerstein 1998). Yoga was and is a primal exploration into ‘Spatial Medicine.’ How can function be altered by changing a person’s shape (Myers 1998)? Yoga’s first practical text, quoted above, was written nearly two thousand years ago. In its entirety, yoga is a highly complex system for self-realization, whose maps and descriptions of the upper realms of mental, emotional, and spiritual states are full of allegorically rich imagery it shares with Hinduism and the healing system of Aryuveda (Lad 1984). The subtleties and range of yoga’s ‘eight-fold path,’ chakras, and meditative states, however beneficial, are beyond our scope here, where we confine ourselves to the ‘limb’ of physical training known as hatha yoga. • Pranayama (breathing practices designed to quiet the mind, induce the relaxation response, and improve autonomic physiology) • Asana (physical postures and movements designed to engage/stretch shortened or bound tissues, strengthen weak muscles, and integrate movement) Both of the first two methods require an element of mindfulness or attention, considered essential to the practice. Mindless repetition of the postures is thought to have less benefit, while ‘any movement done mindfully and with attention to the breath is technically yoga’ (Davis 2009). • verbal cues or guided imagery concerning specific areas to move, relax, or give attention • manual adjustment of the subject by the therapist • pre- and post-therapy body scans to promote proprioceptive awareness of changes • Ashtanga is a vigorous form that requires a higher strength quotient and raises the heart rate and internal body temperature of the practitioner (Swenson 1999). • Vinyasa (‘Flow yoga’) uses a slower form of movement transitioning between postures (Kraftsow 1999). • ‘Classic’ is a more physically static (but still mentally dynamic), positionally precise holding of postures (sometimes supported by physical ‘props’). The Iyengar method of yoga is an influential proponent of this end of the spectrum, as is Bikram yoga (Iyengar 1966; Barnett 2003). • ‘Restorative’ is a variation of static yoga designed to induce deep relaxation in various fully supported poses (Lasater 1995). There are studies indicating beneficial effects of yoga as therapy for certain physiological conditions (Nagendra 1986; Jain et al. 1993; Pilkington et al. 2005). The effect of controlled breathing practices (pranayama) on fascial tissues and physiology is very hard to measure in isolation from other factors, but research points to where common sense would take us: that increased breath will better oxygenate tissues, and breathing movements will strengthen and coordinate the trunk from the neck to the pelvic floor (Farhi 1996; Iyengar 1996; Sherman et al. 2005; Kirkwood et al. 2005; Androjna et al. 2008). The effects of the practice of asana on the fascial tissues share much with the previous chapter on stretching, so these findings need not be repeated here (see Chapter 20). Subjective feelings and anecdotal reports of calm well-being, balance, and spring-in-the-step abound after yoga or yoga therapy, and these feelings are presumed to result from increased hydration of underserved tissues, expanded range of motion, the ability of previously bound tissues to slide on one another, and heightened proprioception and neural integration as areas return to awareness from the ‘sensori-motor amnesia’ cycle (Hanna 1988). More obscure physiologic and spiritual benefits (to the autonomic system, glands, organs, or psychology) are ascribed to particular postures or practices, but these assertions are beyond our ability to prove or even provide useful comment. Provocative research in mechanobiology points to interesting possible global physiological effects of yoga asana (Arora et al. 1999; Langevin et al. 2001; Ingber 2003; Iatridis et al. 2003; Atance et al. 2004). Clearly, different cells have differing optimal mechanical environments, and are sensing and responding to integrin-mediated signaling that arrives via the extracellular fascial matrix. Many of the asana postures and stretches common to yoga therapy are designed to engage or challenge not just a single muscle, muscle group, or connective tissue structure, but rather to engage an entire kinetic chain or ‘myofascial meridian’(Myers 2009). There are upwards of one thousand different asanas and variations in the yogic canon, but the major ones, seen in this way, can be grouped into ‘families’ designed to bring light and emphasis to different sections or issues within each meridian line (Kraftsow 1999). The Superficial Back Line (SBL, Fig. 7.21.1) is a continuous strap of myofascial tissues spanning from the underside of the toes around the back of the body and across the top of the head to the brow ridge. The relative tension in the parts and whole of the SBL modulates the primary and secondary curves of the spine, legs, and feet. The SBL is thus a key component of our ability to maintain an easy upright balance by having the major body-weight segments in vertical alignment. Fig. 7.21.1 • The family of asanas that stretch the Superficial Back Line (A) includes forward bands such as seated or standing flexion, such as Uttanasana; (B&E) Downward Dog; (C) or Child’s Pose; (D). Note that in the Boat (E), reciprocal inhibition is employed between the SBL and the Superficial Front Line (see figure 7.21.2), which must be engaged along with the Deep Front Line (see figure 7.21.4) for this posture. From Myers T 2009 Anatomy Trains, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Yoga as a fascial therapy

Techniques

Yoga and fascia

Yoga asana and myofascial meridians

Forward bends/Superficial Back Line

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Fascia in yoga therapeutics