Extrinsic Contracture Release: Medial Over-the-Top Approach

Pierre Mansat

Aymeric André

Nicolas Bonnevialle

DEFINITION

Multiple techniques have been described for the release of elbow contractures. The medial approach has the advantages of direct access to both the anterior and posterior aspects of the ulnohumeral joint and direct visualization of the ulnar nerve.

Medial-based releases were initially proposed by Wilner,24 whose technique involved medial epicondylectomy and wide dissection.

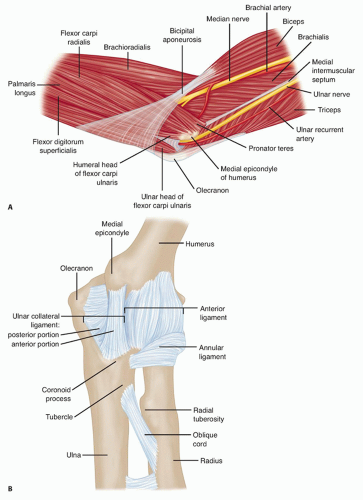

ANATOMY

The medial compartment of the elbow includes the medial side of the ulnohumeral joint, the medial collateral ligament, the flexor-pronator mass, the ulnar nerve, and the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (FIG 1A).

The medial ulnohumeral joint is composed of the medial column, the medial epicondyle, the medial side of the proximal aspect of the ulna, and the coronoid process.

The medial collateral ligament consists of three parts: anterior, posterior, and transverse segments (FIG 1B).

The anterior bundle is the most discrete component, the posterior portion being a thickening of the posterior capsule, and is well defined only in about 90 degrees of flexion.

The transverse component appears to contribute little or nothing to elbow stability.

The medial collateral ligament originates from a broad anteroinferior surface of the epicondyle but not from the condylar elements of the trochlea just inferior to the axis of rotation.18 The ulnar nerve rests on the posterior aspect of the medial epicondyle, but it is not intimately related to the fibers of the anterior bundle of the medial collateral ligament itself.

The flexor-pronator mass includes the pronator teres, the most proximal of the flexor-pronator group; the flexor carpi radialis, which originates just inferior to the origin of the pronator teres at the anteroinferior aspect of the medial epicondyle; the palmaris longus muscle, which arises from the medial epicondyle and from the septa it shares with the flexor carpi radialis and flexor carpi ulnaris; the flexor carpi ulnaris, which is the most posterior of the common flexor tendons originating from the medial epicondyle and from the medial border of the coronoid and the proximal medial aspect of the ulna; and the flexor digitorum superficialis, which is the deepest from the common flexor tendon but superficial to the flexor digitorum profundus.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Diagnosis of the contracture is usually made by identifying a characteristic history and performing a physical examination.

Joint involvement is confirmed by plain radiographs. The anteroposterior (AP) view gives good visualization of the joint line, whereas the lateral view can demonstrate osteophytes on the coronoid and at the tip of the olecranon, even when the joint space is preserved.

The details of the extent of any boney involvement are best observed on computed tomography.

Transverse imaging by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has little use in our practice.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Several options have been proposed for the treatment of elbow contracture.

Nonoperative treatment with mobilization of the elbow through the use of alternating flexion and extension splints17 or dynamic splints8 can provide a good result if it is initiated soon after the contracture develops.

Manipulation with the patient under anesthesia have also been recommended, but loss of motion and ulnar nerve injury have been reported.6

Recently, botulinum toxin has been used to release muscle contracture in order to facilitate elbow rehabilitation and regain motion.20

Nonoperative treatment usually is successful only for extrinsic stiffness that has been present for 6 months or less, and the results can be unpredictable. With failure of nonoperative treatment, surgical release may be indicated. Recently, arthroscopic techniques for capsular release of the elbow have been described; however, open release remains a safe, reproducible option for regaining elbow motion.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications

Contracture release

Stiff elbow

Degenerative arthritis with anterior and posteromedial osteophytes

Ulnar nerve symptoms

Advantages

Allows exposure, protection, and transposition of the ulnar nerve

Preserves the anterior band of the medial collateral ligament

Affords access to the coronoid with intact radial head

Disadvantages

Difficulty in removing heterotopic bone on the lateral side of the joint

Affords poor access to radial head

Preoperative Planning

Before surgery, the decision must be made to approach the capsule from the lateral or medial aspect.

If the ulnar nerve is to be addressed or there is extensive medial or coronoid arthrosis, the medial approach is of value.

If the radiohumeral joint is involved or if a simple release is all that is required, the lateral “column” procedure is carried out.

Positioning

The patient is usually positioned supine, supported by an elbow or a hand table.

Two folded towels should be placed under the scapula.

A sterile tourniquet is positioned.

To expose the posterior joint, the patient’s shoulder should have fairly free external rotation; otherwise, the arm should be positioned over the chest.

Approach

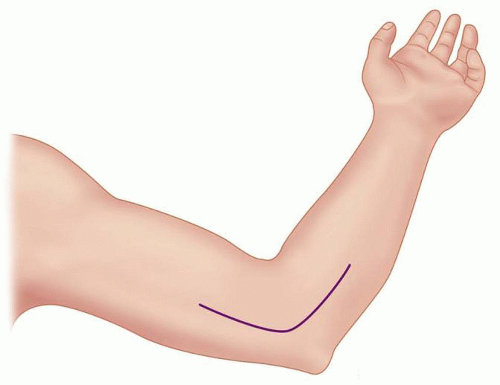

The skin incision may be a midline posterior skin incision or a medial one (FIG 2).

The key to this exposure is the identification of the medial supracondylar ridge of the humerus.

At this level, the surgeon can locate the medial intermuscular septum, the origin of the flexor-pronator muscle mass, and the ulnar nerve.

This site also serves as the starting point of the anterior and posterior subperiosteal extracapsular dissection of the joint.

TECHNIQUE

▪ Exposing the Ulnar Nerve and the Medial Fascia

Once the medial intermuscular septum is identified, the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is identified, traced distally, and protected.

The branching pattern varies, however, so it is occasionally necessary to divide the nerve to gain full exposure and to adequately mobilize the ulnar nerve, especially in revision surgery.

If this is necessary, the nerve is divided as proximally as the skin incision will allow, ensuring that the cut end lies in the subcutaneous fat (TECH FIG 1).

If a previous anterior transposition was performed, the ulnar nerve should be fully identified and mobilized before proceeding.

The surgeon must be prepared to extend the previous incision proximally as necessary.

In this setting, the nerve is often flattened over the medial flexor-pronator muscle mass or it can “subluxate” to a posterior position.

This dissection requires patience and may take considerable time. Dissection of the nerve needs to be carried distally far enough to allow the nerve to sit in the anterior position without being kinked distal to the epicondyle.

The septum is excised from the insertion on the supracondylar ridge to the proximal extent of the wound, usually about 5 to 8 cm.

Many of the veins and perforating arteries at the most distal portion of the septum require cauterization.

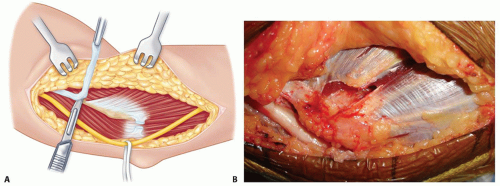

▪ Exposing the Anterior Capsule for Excision and Incision

Once the septum has been excised, the flexor-pronator muscle mass should be divided parallel to the fibers, leaving roughly a 1.5-cm span of flexor carpi ulnaris tendon attached to the epicondyle (TECH FIG 2A,B).

The surgeon then returns the supracondylar ridge and begins elevating the anterior muscle with a Cobb elevator.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree