, Paul D. Siney1 and Patricia A. Fleming1

(1)

The John Charnley Research Institute Wrightington Hospital, Wigan, Lancashire, UK

If it could be guaranteed that the greater trochanter would unite within three weeks when reattached, and without imposing restrictions which would impede rehabilitation, few surgeons would fail to avail themselves of the easy and beautiful access to the hip joint provided by the approach (1979)

In the evolution of the LFA and its introduction into clinical practice Charnley pursued the ideal of mechanical perfection; trochanteric osteotomy and reattachment was part of that philosophy. Even when he was ready to put his final version of the technique of the LFA into print Charnley stated: “Dissatisfaction with reattachment (of the trochanter) has been the cause of many years of delay in writing this book. A method which satisfies the author has at last been found”.

Our objective is to present some aspects of the history and evolution of this method of exposure, show the results and leave it to others to comment, judge and decide by their own experience and long-term results, provided of course that these are continually reviewed.

Historical Aspect

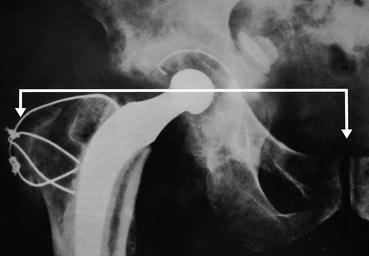

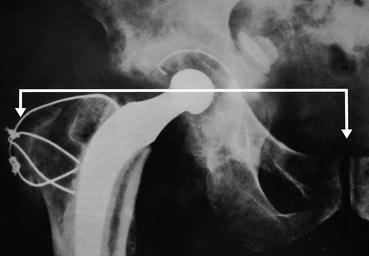

It is probably correct to suggest, on Charnley’s own admission, that it was the late Sir Harry Platt who introduced Charnley to this method of hip exposure. Whoever was the first to introduce this method into clinical practice, it was certainly not for the purpose of total hip arthroplasty. This was the only method that Charnley used routinely for his operation of the LFA. It was not merely for easy access and good exposure, Charnley followed the teaching of Pauwels. Any attempt of reducing the load on the hip joint must include balancing and improving the lever ratios; reducing the medial lever: from the centre of the rotation of the femoral head to mid-line of the body, while increasing the lateral lever: from the centre of the rotation to the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter [1] (Fig. 8.1). Trochanteric osteotomy lends itself to that concept.

Fig. 8.1

Reducing the load on the hip joint must include balancing and improving the lever ratios; reducing the medial lever: from the centre of the rotation of the femoral head to mid-line of the body, while increasing the lateral lever: from the centre of the rotation to the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter

The Cup

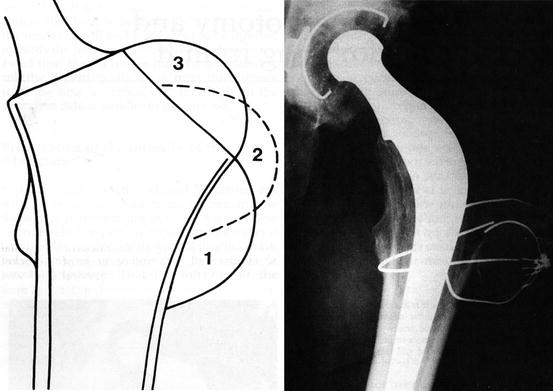

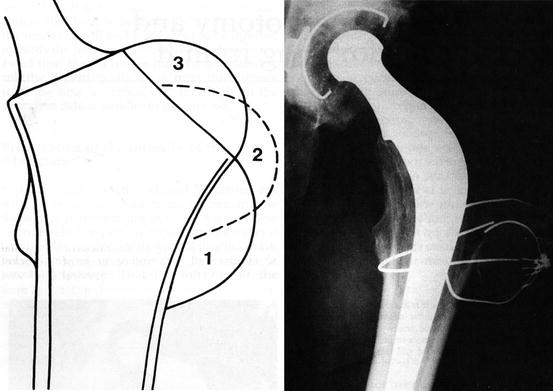

The cup was medialised by reaming the acetabulum, while the trochanter was placed laterally and distally. There was nothing wrong with the concept: what came later sheds some light on the subject. In the original description of the operative technique, the perforator, the deepening and expanding reamers, were all directed towards the patient’s opposite shoulder. The depth was judged by the thickness of the acetabular floor remaining after reaming, thus medialising the cup. To indicate the advantages of lateral and distal placement of the greater trochanter numerical values were used: position 3 – trochanter placed on its original bed; position 1 – trochanter reattached distally past its bed onto the lateral aspect of the shaft of the femur; position 2 – intermediate between 1 and 3 (Fig. 8.2).

Fig. 8.2

Radiograph and diagram showing the advantages of lateral and distal placement of the greater trochanter: position 3 – trochanter placed on its original bed; position 1 – trochanter reattached distally past its bed onto the lateral aspect of the shaft of the femur; position 2 – in between 1 and 3 (Reproduced from: Wroblewski [6]. First described by Charnley [7])

Was the theoretical benefit of medialisation of the cup reflected in the long-term results? Did medialised cups wear less when compared with the rim supported cup? Availability of long term results offered the information (refer to Wear chapter).

The Stem

The medullary canal was approached through the sectioned neck, the trochanteric bed was not encroached upon and as a result the stem was often in a varus position. The intact trochanteric cancellous bed offered a large area of contact, the leg was not lengthened and the patient stayed in bed for up to 3 weeks.

The Trochanter

The method of trochanteric osteotomy, reattachment and the excellent exposure did not attract attention: there were no problems! At this stage of evolution of the operation visiting surgeons admired Charnley’s skill, the excellent exposure offered by trochanteric osteotomy and above all the ease of preparation of the medullary canal and cementing of the stem. Visitors were impressed: perforation of the femoral cortex, let alone the periprosthetic fractures, using the exposure, did not occur.

Post-Operative Routine

“The average stay in hospital is eight weeks” (1961). The post-operative management had clearly a role to play. “After the earlier operations a single plaster hip spica was applied but in the last two years it has been found unnecessary to use anything more than a special triangular pillow between the knees.” (The reason for this apparently sudden change was that one patient – while awaiting application of the plaster – fell out of bed. No damage was done, henceforth, no plaster spica). “Full weight bearing is permitted at 3 weeks” (1963).

Changing Patterns

This digression to the very origins of the LFA technique must not be seen to be out of place. Surgery of the hip joint was evolving. Tuberculosis was the common problem. Improvements in sanitation, screening and vaccination resulted in the decline of the disease. Advent of anti-tuberculous drugs allowed surgical intervention and early mobilisation reducing the length of inpatient stay from years to months or even weeks.

Attention was now focused on the arthritic hip. Hip fusion, osteotomy and plaster fixation, then internal fixation and early mobilisation was merely a changing pattern of hip pathology presenting for the available treatment. Eight weeks of bed rest after the LFA was, by comparison, a tremendous advance. Even the most recent changes allowing discharge within days of surgery must be viewed as the changing pattern imposed by changing indications, type of surgery, patient selection, availability of after-care facilities, as well as the financial implications of medical treatment in general and not some newly discovered principle.

Changing Practice

A number of events coming in quick succession changed the practice. In an attempt to reduce the already very low post-operative dislocation rate, transverse reaming of the acetabulum was advocated, bringing the cup down to the anatomical level. The first fractured stem presented in 1968. While this complication was still in single figures it was clear that the stem was often in varus position; valgus and even excessive valgus became the teaching. What followed was more obvious, in retrospect. Transverse reaming of the acetabulum and anatomical position of the cup lengthened the limb. The stem, now in valgus, not only lengthened the limb further but also encroached into the cancellous bed of the trochanter. The trochanter would not come to lie “peacefully” onto its bed now with a reduced area of contact; it had to be reattached with the hip in an abduction position. The patients were encouraged to get up early: “Pillow for 5 days, up at 2 days” – became the post-operative routine: The result: trochanteric non-union.

The explanation – a pain free mobile hip allows free adduction movement, this may lift the trochanter off its bed slackening the wires which then fail by fatigue and also in a brittle manner. It was during this period that numerous methods of trochanteric reattachment were designed and tested both experimentally and clinically. It is this sequence of events that became the source of polarization of opinions on the exposure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree