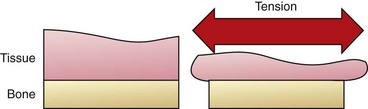

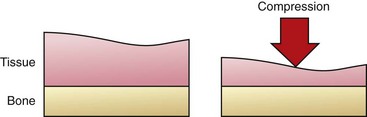

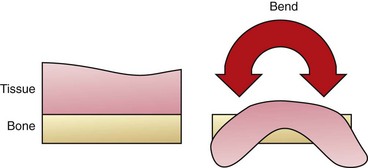

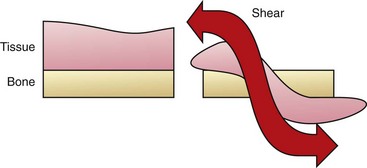

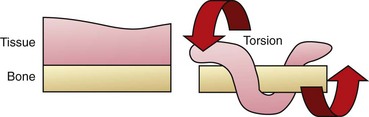

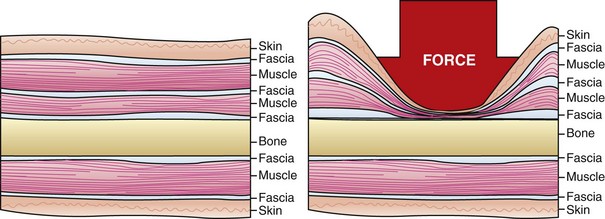

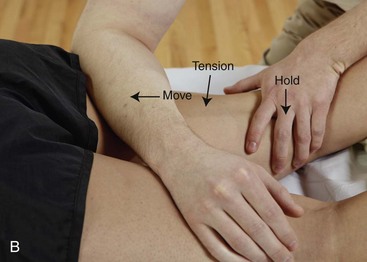

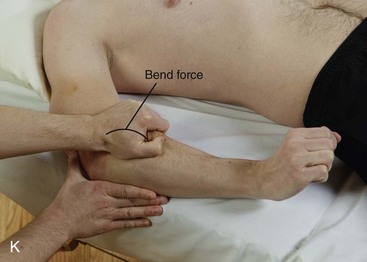

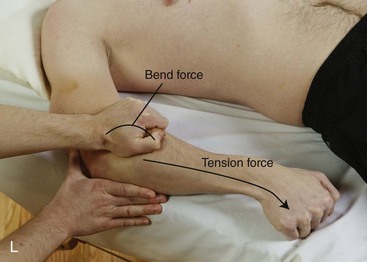

Chapter 3 Sport/Fitness and Rehabilitation Outcomes General Massage Benefits and Safety Fluid Movement—Blood and Lymph Research Related to Massage, Tissue Healing, and Musculoskeletal Pain After completing this chapter, the student will be able to perform the following: 1 Understand and describe massage outcomes based on known and theoretical physiologic mechanisms. 2 List and describe four general outcomes for the athlete/fitness and physical rehabilitation population. 3 Explain evidence that indicates that massage is a supportive and safe intervention. 4 Describe the potential for adverse effects from massage application. The terms bodywork and massage encompass a huge array of methods and philosophies. This chapter does not intend to teach the application of these methods and styles because excellent instructional texts already exist (see the recommended reading list at the end of the book). The focus of this chapter is to describe the underlying theme of all methods and their relationship to sport and fitness goals, measurable outcomes, and physiologic pleasurable mechanisms, as well as research currently being conducted to support these results (Bialosky et al., 2009). Additionally, logical explanations will be presented for some massage results even though research has not totally proved the response correlation. Many different types of scientific research methods are available. Some provide better evidence than others. Also, some evidence is based on clinical experience and expert opinion. The massage therapy profession is now being challenged to function in an evidence-based and informed manner (Box 3-1). Massage effects appear to be determined by a combination of reflexive and mechanical responses to forces imposed on the body by massage (Box 3-2) (Figures 3-1 and 3-2). FIGURE 3-2 Examples of mechanical force loading during massage. A, Tension loading occurs when tissue is elongated. Gliding massage methods and stretching can create tension forces in tissues. B, Tension forces occur as tissues are stretched. C, Compression loading occurs when force moves into tissues at a 90-degree angle. In this example, a forearm is used to create compression force in tissues of the shoulder with the client in a side-lying position. D, Forearm used to compress calf with client in side-lying position. E, Bending loading. In this example, the hands are used to bend tissues of the calf around the thumbs. F, Using force compression to displace tissues of the calf, creating a bending force. G, Example of shear loading. The tissues of the calf are pushed down. H, Then the same tissues as in part G are pulled up. The back-and-forth movement creates the shear force. I, Torsion forces twist tissue around a fixed point. In this example, thigh tissues are twisted around the femur. J, Rotational or torsion forces in massage are generated by kneading. Move tissues by pushing one hand forward and around the fixed point while pulling the other hand back and around. K, Example of combined loading when two or more mechanical forces are generated. Bending force caused by grasping and lifting. L, Then client creates the tension force and the wrist is moved. M, In this example of combined loading, compressive force is created as the therapist presses down on arm tissues and then moves the forearm back and forth to add torsion, bend, and shear forces. • Local tissue repair, as with a sprain or contusion • Connective tissue normalization that affects elasticity, stiffness, and strength, as when pliability of scar tissue or overall flexibility is improved • Shifts in pressure gradients to influence body fluid movement • Neuromuscular function interfacing with the muscle length-tension relationship; force couples; motor tone of muscles; concentric, eccentric, and isometric functions; and contraction patterns of muscles working together to support efficient movement • Mood and pain modulation through shifts in ANS function, yielding neurochemical and neuroendocrine responses • Increased immune response to support systemic health and healing 2. List and describe four general outcomes for the athlete/fitness and physical rehabilitation population. These outcomes can be classified as four goal patterns for sport and fitness: • Achieve normal function through rehabilitation and conditioning • Reduce the negative effects that performance demand places on the body in excess of normal function Performance enhancement requires increasing demand on the body through practice. Maintaining performance involves attention to demand on the body and reinforcement. Each individual has a range of peak performance with the triad of body/mind/spirit function in his or her optimal range. As discussed in Chapter 8, this is called “the zone.” Peak performance is difficult to maintain for extended periods of time. Recovery is necessary to restore depleted energy and regenerate damaged soft tissue. Most athletes train at levels below peak performance with the desired outcome of reaching that peak during competition. This process is compromised if ongoing competition is extended over periods of time. This is common among professional athletes, especially in team sports such as baseball, basketball, football, hockey, and soccer. The “why massage works” remains elusive, but recurring findings suggest possible physiologic mechanisms for massage benefit. One study by Field and her associates (2005) is particularly relevant for this text because it deals with serotonin, which is associated with body pain modulation mechanisms. In other studies, Diego et al. (2004, 2009) speaks to how massage needs to be applied with sufficient nonpainful compressive force to stimulate an anti-arousal response, and that massage that is considered light tends to stimulate the sympathetic ANS response (Field et al., 2010). Pressure-based massage produces different physiologic changes than are produced by light touch (Sefton et al., 2011; Rapaport et al., 2010). Application of moderate pressure massage appears necessary to influence hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function (Rapaport et al., 2010; Field et al., 2010) and diastolic blood pressure (Moraska et al., 2010). Light or moderate pressure massage (or a combination) may reduce the sensitivity of spinal nociceptive reflexes (Sefton et al., 2011; Roberts, 2011). Light pressure gliding stroke–based massage has been shown to lower heart rate and systolic blood pressure and to decrease the deterioration of natural killer cell activity; however, no effects were identified for cortisol levels and diastolic blood pressure (Hillier et al., 2010; Billhult et al., 2009). Pressure levels used during massage are an important concept for athletes seeking restorative benefits from massage. It appears that moderate to light pressure can affect generalized restorative function, and deep aggressive massage application is not necessary to achieve these benefits. The study “Massage Reduces Pain Perception and Hyperalgesia in Experimental Muscle Pain: A Randomized, Controlled Trial” (Frey Law et al., 2008) suggests that massage is capable of reducing myalgia symptoms by approximately 25% to 50% (extent of effect varies with the assessment technique used to measure pain). The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of massage on pressure pain thresholds (PPTs) and perceived pain. Researchers used delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) as a model of myalgia (muscle pain). This condition is a major issue for athletes and those attempting to integrate an exercise program into their lifestyle. Massage is not always the best technique for managing symptoms. According to Hanley et al. (2003), despite very strong patient preference for therapeutic massage, it did not show any benefit over a relaxation tape used to control postsurgery pain. Massage was effective in reducing anxiety but was no more effective than relaxing in a quiet room (Sherman et al., 2010). Although these studies indicate that massage is effective for anxiety management, it is no more effective than other relaxation interventions. Key, however, is that people liked massage, which is an important factor in compliance with treatment. Muller-Oerlinghausen et al. (2004) concluded that slow-stroke massage is suitable as an intervention for depression, along with other treatment, and is readily accepted by very ill patients. A reduction in distress has been noted among oncology patients in response to massage, regardless of gender, age, ethnicity, or cancer type. When any treatment is assessed, safety is a primary concern (i.e., do no harm). If harm is possible, then the benefits of receiving massage must exceed the potential for harm. A summary of a review of massage safety by Ernst et al. (2006) concludes that massage is generally safe. Massage is not entirely risk free, and we need to be aware of potential harm. However, serious adverse effects are rare. Most adverse effects resulting from massage were associated with aggressive types of massage or massage delivered by untrained individuals. Also, these effects were associated most often with massage techniques other than “Swedish” (classic) massage. These findings are extremely important for those working with athletes. In general, over the years, “sport massage” has incorporated aggressive methods. Another situation in which adverse effects may occur is when massage interferes with various types of implants such as stents, ports, prostheses, and so forth. Haskal (2008), in the Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, reported a case where a stent placed in the lower limb as treatment for peripheral artery disease migrated to the right atrium after 3 years. Open heart surgery was required to remove the embedded stent fragments. The mechanism attributed with dislodging and moving the stent was deep tissue massage of the thigh. Although this outcome is rare, it is important to pay attention to adverse effects caused by massage. Athletes may have had various surgeries to repair injuries. Often various stabilizing devices such as pins and screws are used. Care needs to be taken to avoid compressing tissues into these areas to prevent potential damage to tissues as they are pushed into the stabilizing devices. Also, the “deep tissue” approach is often used with athletes without considering the potential for damage. Moderate to heavy pressure applied with a small contact such as at the tip of the elbow or with a massage implement such as a hand-held pressure device is more likely to cause tissue damage than pressure applied with a broad contact such as the forearm. Aggressive stretching procedures provide other opportunities for structural damage. Benefits of stretching in general are being questioned (see later in chapter). A physiologic and safe range of motion has been determined for joints. Any stretching beyond this motion increases the potential for harm. In a cross-sectional study of 100 clients, 10% of massage clients experienced some minor discomfort after the massage session; however, 23% experienced unexpected, nonmusculoskeletal positive side effects. Most negative symptoms started within 12 hours after the massage and lasted for no longer than 36 hours. Most of the positive benefits began to be noted immediately after massage and lasted longer than 48 hours. No major side effects occurred during this study (Cambron et al., 2007). Soreness after massage can affect performance for an athlete. Based on findings of this study, it may be prudent for the athlete to avoid massage a day and a half before competition; however, because the benefits last for at least 2 days, the athlete should still experience positive results from massage. Massage therapy appears to have a beneficial effect on anxiety levels; this is important for the management of performance anxiety experienced by many athletes. The therapeutic relationship established between massage therapist and client is similar to that seen in psychotherapy, a treatment that relies on communication and the therapeutic relationship to produce effects. It is possible that massage effects are related to the therapeutic relationship (Moyer et al., 2004). Excessive sympathetic output causes most of the stress-related diseases and dysfunctions, including headache, gastrointestinal difficulties, high blood pressure, anxiety, muscle tension and aches, and sexual dysfunction.

Evidence for Sports Massage Benefit

Evidence for Massage

How the Body Responds to Massage

Sport/Fitness and Rehabilitation Outcomes

Performance Enhancement/Recovery

General Massage Benefits and Safety

Pressure Depth

Adverse Effect

Potential for Harm

Neuroendocrine Regulation

Mood

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree