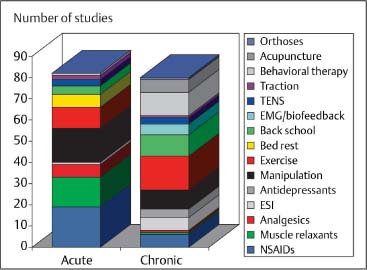

10 Evidence Base in Manual Medicine for the Treatment of Back Pain Syndromes: Background, Status, and Practice The use of the hands as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool has a long history in the treatment of disorders affecting the spine and the limb joints. Ever since the introduction of osteopathic and chiropractic medicine in the late 19th century, the use of the hands as a major component in patient management was considered as an “outside” method, one that would not be acceptable to the allopathic medical profession for most of the 20th century as well. Manual medicine, even when practiced by medical doctors, was routinely labeled as unscientific. In the past, the discourse between medical doctors (M.D.s), chiropractors (D.C.s) and osteopathic physicians (D.O.s) may often have been based on personal and emotional exchanges and preconceived notions “along professional lines,” rather than engaging each other in constructive discussions that would help establish a common language and understanding. In the 1960s and 1970s, however, the interest in and study of manipulative procedures as one of the ways to address pain syndromes grew steadily among allopathic physicians, both in Europe and the United States and in other parts of the world. While there may be several reasons for such a development, three major factors seem stand out: (1) an ever-increasing body of “successful” cases that had previously been recalcitrant to other forms of treatment; (2) the growing interest among patients to be treated within an individualized and hands-on “holistic” approach; and (3) the growing realization that surgical intervention (introduced by Mixter and Barr in 1934) for painful back disorders has limited success and application. In 1958 the Swiss rheumatologist John-Claude Terrier, M.D. founded the International Federation of Manual Medicine (FIMM, Fédération Internationale des Médecins Manuels), which has grown since to a physicians’ organization of more than 6 000 members and representing 29 countries. During the past 30 years, there has also been a significant growth in the numbers of graduates from osteopathic, chiropractic, and physical therapy institutions in the United States. Since the mid-1980s, there has been less resistance by the orthodox branch of medicine to manual medicine approaches. Since 1992 students at the medical school in Zurich can matriculate in a course on manual medicine diagnosis and interest is high. In the same year, the medical faculty of Otago in Christchurch, New Zealand, started a program that leads to a diploma in manual medicine. A similar course of education was created in 1993 in Australia. In a number of European countries, the medical student of the classical medical curriculum is exposed to manual medicine (in the Czech Republic, Austria, France, and Germany, for instance). According to our own survey, 640 000 manual medicine procedures are performed annually by physicians in Switzerland, approximately 5 million manipulations in Germany, and 340 000 in Austria. According to the survey, manual medicine treatment for low back pain is applied 805 times per year, and 350 times per year for treatment of cervical spine syndromes (unpublished data from Swiss Medical Association of Manual Medicine SAMM). Depending on the medical specialty, manual medicine treatment comprises between 20–50% of all medical treatment. The number of treatments applied for each patient depends not only on the medical specialty but also on the clinical situation overall. Whereas the general practitioner applies manual medicine techniques in 1.4 treatments per patient, the specialist may treat the patient between four and five times. One explanation for the greater utilization of manual medicine by specialists is that often the patient has a chronic situation whereas the primary care physician may treat primarily acute presentations or exacerbations. A growing number of published reports have investigated the effectiveness and cost considerations of spinal manipulative procedures either alone or in comparison with other treatment interventions (Fig. 10.1). Most of the studies have concentrated on studying the high-velocity/low-amplitude (HVLA) thrusting maneuvers (“spinal manipulation,” or simply “manipulation,” or “thrust,” or also mobilization-with impulse-techniques: see Chapter 2 for definitions). These studies typically do not make a distinction between the thrusting maneuvers and the low-velocity mobilization techniques (www.backpaineurope.org). The entire manual medicine armamentarium, which includes the thrusting as well as the non-thrusting soft-tissue (or other) techniques, has been referred to as a single “spinal manipulation package” (Harvey et al., 2003). Fig. 10.1 Schematic representation of the number of different interventions included in the systematic review by van Tulder et al. (1997). The authors reviewed 150 articles, of which 81 dealt with chronic pain, 63 with acute pain, and one article with both. The specific distribution was as follows:

Brief Historical Background

Effectiveness and Cost Considerations: Evidence and Recommendations

Left-hand column: |

|

Interventions for acute pain | Number of studies |

Pharmacologic intervention: |

|

NSAIDs | 19 |

Muscle relaxants | 14 |

Analgesics | 6 |

ESI | 1 |

Nonpharmacologic intervention (physical and cognitive/behavioral therapies): | |

Manipulation | 16 |

Exercise | 10 |

Bed rest | 6 |

Back school | 4 |

TENS | 3 |

Traction | 2 |

Behavioral therapy |

|