Ethical issues in chronic care

Objectives

New terms and ideas you will encounter in this chapter

chronic condition

chronic care team

experimental treatment

Topics in this chapter introduced in earlier chapters

| Topic | Introduced in chapter |

| Ethics committee and ethics consultation | 1 |

| A caring response | 2 |

| Locus of authority problem | 2 |

| Moral distress | 3 |

| Quality of life | 3 |

| Utilitarianism | 3 |

| Principles approach | 3 |

| Nonmaleficence | 3 |

| Beneficence | 3 |

| The health care team | 9 |

| Communication | 9 |

| Shared decision making | 11 |

| Informed consent | 12 |

| Assent | 12 |

Introduction

With more than 100 million people in the United States who have at least one chronic condition, chronic care is demanding the attention of health professionals, families, and the health care system more than ever before.1 Many factors contribute to the increase in the number of chronic conditions and symptoms when compared with even a few years ago. Among these are advances in neonatal intensive care, the increasing incidence rate of long-term survival after traumatic brain injury occurring anywhere across the life span, and an increase in adult longevity. These are just some sources of this growing population of patients nationally and globally.

The term chronic condition (from kronos, which means “time” in Latin) focuses attention on long-term management of a condition in contrast to one that is either quickly addressed or is at the end of life. It does not denote that the person eventually will die of the condition, although some do. Examples of the latter include cystic fibrosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The common denominator in chronic conditions is that the symptoms persist over time, some for months, years, or a lifetime. You may know someone (or be a person) with one of the previous conditions or someone who lives with symptoms of arthritis, diabetes, clinical depression, schizophrenia, dyslexia, or one of the dementias. The presence of all these forms lends support to the idea that in your generation of the health professionals, most of you will be deeply involved in the treatment of chronic symptoms and the functional impairment that often accompanies them. Currently, the clinical management of patients with chronic conditions often lacks coordination among specialties, providing plenty of room for you to become advocates for improving the quality of care for such persons.2 This chapter focuses directly on the ethical challenges this population presents and relevant details for achieving a caring response to this condition. A caring response is not unique in comparison with other types of conditions, but at times, the challenges present in slightly different forms. It is noteworthy that in almost all chronic conditions the patient interacts with a whole team of people, sometimes with a chronic care team specifically, but other times with teams devoted to a particular disease or injury. This in itself creates an environment of multiple relationships that affect the patient and, very often, include the family or others who provide care besides health professionals.

Reflection

Do you have a friend, family member, or colleague who has a chronic condition that necessitates ongoing clinical interventions? Perhaps you have one yourself. What are the major challenges that you think, or know, face this person? Are there disruptions in everyday activity that they experience? How are their daily routines different from others’? Jot down a few notes so that as you go through the chapter you can relate that person’s situation back to the opportunities health professionals have to provide patient-centered care.

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

As you have experienced in previous chapters, to further help set your thinking, you have an opportunity to examine a narrative, this one of a family who is interacting with the health care system because one family member is in a situation that requires ongoing care.

This care team, the patient, and the family are in a relationship that is not unusual for patients with chronic conditions. Some characteristics of this type of team relationship are:

• the shared concern for and loyalty to the patient;

• the long experience of working with each other;

• knowledge that the family caregivers are very much affected by the patient’s condition; and

In addition, the complexity and uncertainty facing all of them about what to do next is not unusual. Chronic, long-term conditions always continue to evolve over time, unlike more acute conditions. We turn now to the challenges they face together.

The goal: a caring response

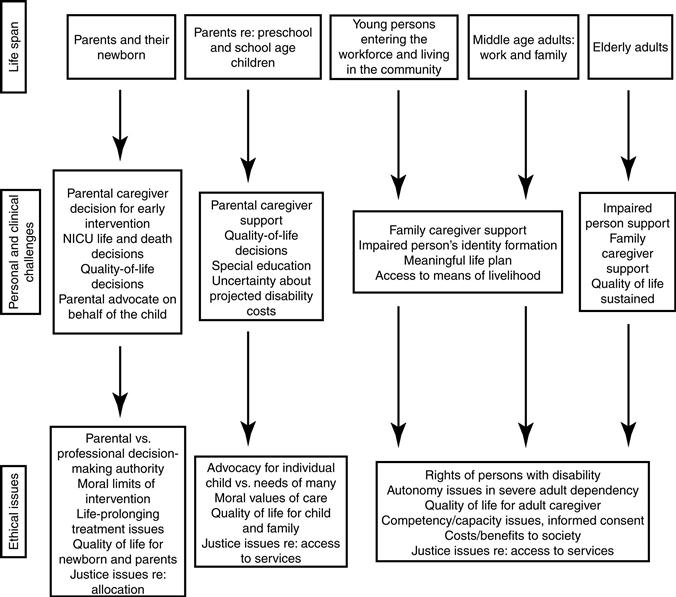

The means by which the goal of a caring response in this situation can be realized is, in many regards, similar to those in any other type of situation. For instance, the care must be personalized to the needs of the patient’s specific situation. However, as we already noted, a key consideration that distinguishes a chronic care situation from many others is that collectively the interventions extend over a long period, sometimes from the patient’s birth to her or his adulthood and old age. Figure 13-1 outlines several dimensions of the range and possible lifelong duration of chronic conditions.

We can predict that in Mary Elizabeth’s case, she (and until she reaches adulthood, her parents) will be in relationships with health professionals on a regular basis. For her, there is a high probability this will continue throughout her entire life.3

There also are several generic considerations that apply to all patients with chronic conditions.

First, for most patients, their expectations of the health professional or team is not to effect a cure, although if a cure would become known, the focus obviously should shift in that direction.

Second, the point of accepting clinical interventions is to protect or improve the quality of life, whether it be through prevention of secondary symptoms, freedom from pain or other discomfort, or rehabilitation designed to help build or sustain important functions, relationships, and roles. The health fostering and health maintenance interventions for the patient with one ongoing condition (complete with its evolving symptoms over months or years) casts the challenge in a somewhat different light than those directed to acute symptoms. It is a balance of periods of illness and wellness. Persons with a chronic condition have been found to experience challenges to life meaning, needing to balance freedom to do as they want and feel they need to do with loss of control.4

Third, and related to the second, the patient counts on the professionals to design treatment programs with the idea that the family (or other significant personal caregiver) is an essential consideration. More than in most other types of treatment planning, the health professional team must take the family caregivers’ well-being into account (see later for further discussion of this point). In Mary Elizabeth’s or other children’s situations, a parent or other adult guardian is the legal spokesperson. The same is true for adults with limited capacity, as discussed in Chapter 12. There are not only ethical but also economic and other practical reasons for making decisions that are appropriate for the family caregivers’ needs, and the patient’s.5

Fourth, clinically and socially, the patient needs the professionals to be acutely aware that “the chronically ill” may have difficulty harnessing appropriate long-term care services. A caring response on the part of the professional must include concerted advocacy efforts designed to counteract and denounce such discrimination and dehumanizing experiences. This extended role of the health professions is discussed in Section V of this book.

Reflection

Can you think of other considerations that should inform health professionals who are working with chronic conditions but might not be as important in acute care settings? List them here.

Again, the six-step process of ethical decision making can be called on for assessing and discerning an ethical course of action in chronic care situations.

The six-step process in chronic care situations

Let us return to the McDonalds and the cystic fibrosis team; we pick up the story at the juncture where the team has become divided about the decision made by the team leader. The first step is to gather relevant information.

Step 1: gather relevant information

The team is paying attention to information that has caused them concern. They know that the drug has been approved for human use in selected situations, such as Mary Elizabeth’s case, and that the alternatives for Mary Elizabeth are few. They know all too well that a lung transplant is a high-risk surgery and that for some patients the symptoms of cystic fibrosis grow more serious during the changes of puberty and adulthood.

Evolving clinical status over time

Unlike most health professionals who work in acute care situations, the chronic care team (in this case, the specialized cystic fibrosis team) is in a position to assess a patient’s status over a period of time. The members have been working with the McDonalds for several years; therefore, they have a reasonable understanding of Mary Elizabeth’s current clinical condition compared with previously. Her condition can be characterized as stable, with the only big unknown being the patient’s prepubesence; however, they can compare her condition with conditions of other similarly situated patients because their clinical expertise is in cystic fibrosis and respiratory disease.

Like many teams, they are now faced with a situation in which their certainty is faltering. They know that so far the team has been able to help the McDonalds manage Mary Elizabeth’s symptoms. Unfortunately, at this pivotal moment in the team’s relationship, they themselves are divided because of the uncertainty of what is best for Mary Elizabeth, a challenge that so often creates distress for teams working with chronic conditions. Their firsthand experience with the proposed course of action for Mary Elizabeth is limited to the serious negative outcome it had for their one other patient on the unit, an 8-year-old child. They will have to do their homework regarding this ongoing clinical trial and also regarding the surgical option of lung transplant. Is the experimental approach appropriate for a young patient just entering puberty? There is no evidence of long-term effects because the intervention is so new. How does this weigh in the decision?

Team effects

Fortunately, overall the professionals believe they are privileged to work with a group of outstanding colleagues in this field of medicine, at one of the world’s top academic medical centers specializing in respiratory and pulmonary disease. The team is a “dream team” (most of the time!), hitting the rough spots with their common goals to guide them and with deep respect for each other’s competence.

It is relevant information that similar to most chronic care situations, the family caregivers have developed a deep trust in the team as a unit. The family must feel free to raise questions, express their emotions, and in other ways show their concern within the current situation. When this trust breaks down, the negative effects on the family may haunt them for years.6 For the McDonalds’ well-being, all activity should be pursued in a manner that allows that trust to be sustained, no matter the actual treatment approach, experimental or transplant. This, of course, means the team be totally trustworthy (Figure 13-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree