In this article, the epidemiology of back pain and the use of a variety of treatments for back pain in the United States are reviewed. The dilemma faced by medical providers caring for patients with low back pain is examined in the context of epidemiologic data. Back pain is becoming increasingly common and a growing number of treatment options are being used with increasing frequency in clinical practice. However, limited evidence exists to demonstrate the effectiveness of these treatments. In addition, health-related quality of life for persons with back pain is not improving despite the availability and use of an expanding array of treatments. This dilemma poses a difficult challenge for medical providers treating individual patients who suffer from back pain.

Spine-related disorders are among the most frequently encountered problems in clinical medicine. Low back pain (LBP) alone affects up to 80% of the population at some point in life, and 1% to 2% of the United States adult population is disabled because of LBP. The substantial need for care of these patients, coupled with our poor understanding of the fundamental basis of LBP in many individuals, has led to an ever-expanding array of treatment options, including medications, manipulative care, percutaneous interventional spine procedures, and an increasing repertoire of surgical approaches. The estimated total cost of direct medical expenditures in the United States for spine care in 2006 was more than $85 billion, and the data suggest that the use and costs of spine care have been increasing at an alarming rate in recent years. Self-reported health status among people with spine problems (including physical functioning, mental health, work, and social limitations) does not seem to be improving, and the overall numbers of people seeking Social Security Disability Insurance for spine-related problems and the percentage of people with disability caused by musculoskeletal pain are increasing. Complication rates, including deaths, associated with treatments for spinal pain are also increasing. The statistics are concerning and raise a fundamental question: are spine problems worsening over time or are we simply using an increasing number of costly treatments that are not effective?

Valuable insights into this question can be obtained by examining the available epidemiologic data on spinal pain and treatment. This article addresses in particular the epidemiologic data on percutaneous and surgical spinal procedures and examines national trends in the use of noninterventional treatments such as physical therapy and exercise programs, and opioid medications. The costs associated with these treatments, the potential risks, and the overall effect on the quality of care provided to persons with spine problems in the United States are also examined.

Prevalence of LBP

Despite the vast amount of research devoted to LBP, the epidemiology of this condition is not well understood, and the overall prevalence of LBP in the United States is unclear. There are several techniques for estimating the prevalence of spine problems, including survey techniques as well as the use of medical billing claims data. Each method has its strengths and weaknesses. Retrospective surveys obtain information directly from affected individuals but may be subject to recall bias. Claims-based data may avoid this limitation and are not dependent on individual reporting but detect only those subjects whose physicians coded for back pain associated with a given episode of care in the office. Additional challenges arise from heterogeneity in many other aspects of published studies, including the definitions of LBP that are used. The varying methodologies often lead to different patient groups being studied, which can be problematic from clinical and policy perspectives. Based on health care use data (ie, people who present to a health care provider for care for LBP), the prevalence estimates for LBP are as low as 12% to 15%. However, estimates from self-report survey data on the prevalence of LBP range from 28% to 40% of the population depending on the methodology used.

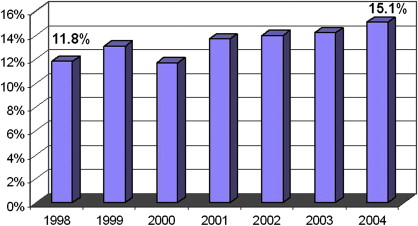

Given the difficulty associated with accurately estimating the prevalence of LBP at any specific time, it seems apparent that there are also difficulties with assessing changes in prevalence over time. A recent study reported telephone survey data collected in 1992 and again in 2006 from a sample in North Carolina indicating that the prevalence of chronic, disabling LBP rose significantly during that time frame, increasing from 3.9% of the population in 1992 to 10.2% in 2006. Although this study was not designed to address causation, the investigators suggest that increasing rates of obesity, depression, or other psychosocial factors may explain this increase in LBP prevalence. Claims-based data seem to indicate a smaller increase in prevalence. The percentage of people presenting to physician offices for LBP steadily, but only slightly, increased from 12% in 1998 to 15% in 2004 ( Fig. 1 ). Although both sets of data could suggest that the overall prevalence of LBP is increasing, it is difficult to tell to what degree these changes represents a true increase in the proportion of the population suffering from LBP versus a change in the propensity of people to either report or seek care for low back complaints. If it is the latter, this situation may represent evolving societal beliefs about pain rather than a change in the number of people who suffer from LBP.

The uncertainty regarding a potential increase in the prevalence of LBP in the US population becomes relevant when analyzing the array of data indicating escalating rates of use of health care services related to LBP. Is the increase in use due to an increase in the relative number of patients with pain, an increase in the percentage of those with pain seeking and/or receiving care, or, as was suggested in recent data from Martin and colleagues, an increase in the per-patient use of care? These questions are important when considering the policy and care implications because the answers speak to the efficacy of, and hence necessity for, specific treatments. Given the available data, the answer is likely that the increasing use rates represent a combination of factors including an increased prevalence of chronic LBP, changes in the treatments used, and changes in societal beliefs regarding pain.

The use of interventional spine procedures

Interventional spine procedures have been used for many decades for a variety of spinal disorders and range from percutaneous injections to surgery. For a variety of reasons, there has been a recent proliferation in the number of techniques available for use and marked increases in the use rates for many of the procedures. Percutaneous interventions include epidural steroid injections (ESIs) via several different approaches, facet/zygapophysial joint (z-joint) procedures, spinal cord stimulation, several intradiscal procedures, and, more recently, procedures intended to remove disc or other material in the spinal canal or to obtain segmental fusion. Surgical procedures range from well-established approaches for discectomy and/or spinal canal decompression to multiple means of addressing segmental fusion using several different approaches, materials, instruments, and indications. However, the evidence to support the use of many of these procedures is limited.

From the surgical perspective, there are sound data on the efficacy of discectomy for acute radicular pain associated with a disc herniation, decompressive laminectomy for symptomatic spinal stenosis, and fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis in well-selected patients. However, selecting appropriate candidates for surgery can be challenging because of variability in diagnosis and characterizing clinical and radiographic characteristics of these conditions. In addition, the clinical benefit of surgery even in well-selected patients can wane, and many patients may do just as well long-term with more conservative options. The data on the efficacy of surgery for isolated LBP are more suspect, and there are many additional patients in whom surgical procedures are either not indicated or contraindicated because of other issues. Surgical care also may carry significant risks and costs.

Because the role of surgery is limited for the larger population of patients with low back pain, there is a need for less invasive options. As noted earlier, several percutaneous procedures for spinal disorders have been developed and are frequently used clinically, most with limited scientific evidence of efficacy. The most commonly used and studied procedures of this type are ESIs, followed in frequency by z-joint procedures, which include intraarticular injections, medial branch blocks, and radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN). The use of each of these techniques has increased, and the evidence to support their use varies depending on the location in the spine (eg, cervical vs lumbar spine) as well as specific characteristics of the spinal disorder (eg, acute sciatica) and patient (eg, worker’s compensation status). The supportive evidence that is available for these procedures predominantly notes short-term improvements in pain. However, even in the best of circumstances the evidence for long-term benefit from any of these is lacking. To better understand the role of interventional care in the management of spinal pain, this review focuses on ESIs because similar trends and issues exist for the other procedures.

Epidural steroid injections

Although ESIs for the treatment of lumbosacral radicular pain were first introduced in the early 1950s, there has been a lot of interest recently in the use of these injections as an alternative to more invasive surgical procedures for treating spinal pain. Since the introduction pf ESIs, many investigators have examined them for the treatment of lumbosacral radiculopathy as well as axial (nonradicular) spinal pain syndromes. Although most studies have addressed the use of ESIs for isolated lumbosacral radiculopathy resulting from discogenic or other causes, some investigators have advocated their use for more diffuse symptoms associated with lumbar spinal stenosis. The current literature reports success rates of 18% to 90% for ESIs, depending on methodology, outcome measures, patient selection, and technique. Some studies, but not all, have found that ESIs can offer short-term pain reduction to a select group of patients, but there is little evidence of long-term improvement in pain or function. Given the overall spectrum of treatment approaches available for spinal pain, short-term pain relief can offer significant clinical benefits in appropriate circumstances, and this seems to be the primary beneficial effect of ESIs advocated by many investigators.

Several studies have attempted to examine the influence of ESIs on the subsequent need for lumbar surgery as an outcome measure. The results have been mixed. An initial prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Riew and colleagues reported that a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving transforaminal ESIs with anesthetic and corticosteroid opted not to have surgery compared with a control group receiving similar procedures with anesthetic alone. This study followed patients for up to 2 years after the first injection. However, in a separate report on 5-year follow-up of the same patients, there were no differences between the treatment and control groups in terms of lumbar surgery. A significant percentage of the treatment group was lost to follow-up for this study, making it difficult to draw any definitive conclusions from these data. A more recent study by Schaufele and colleagues in 2006 compared interlaminar versus transforaminal ESIs for persons with chronic LBP who had failed other conservative treatments. In this retrospective case-control study of 40 patients, the investigators found that 2 (10%) of the patients receiving transforaminal ESIs and 5 (25%) of the patients receiving interlaminar ESIs underwent subsequent lumbar surgery within 1 year after the initial injection. Follow-up beyond 1 year was not reported for these patients. Although the sample size in this study is small, this study is representative of the type of evidence available. Overall, the data indicating a significant effect of ESIs on surgical rates are not robust.

Some limited data are available on the cost-effectiveness of ESIs. Price and colleagues performed an RCT of ESIs in the United Kingdom and concluded that they did not meet the national guidelines for cost-effectiveness, specifically noting that “ESIs do not provide good value for money.” The investigators believed that further research is needed to compare alternative treatments for LBP and to identify subgroups of patients who might benefit more from ESIs. One drawback of this study is that it was performed in the United Kingdom, where there is a national health service, so it is unclear how applicable their cost analysis is to the US population. To date, there have been no cost-effectiveness studies of ESIs or other interventional pain procedures in the United States.

Regardless of which outcome is considered, one of the biggest challenges in interpreting the literature regarding the efficacy or effectiveness of ESIs is the paucity of high-quality RCTs. A recent survey of the published literature shows that there have been 18 RCTs of ESIs compared with placebo or control treatment for a variety of LBP conditions in the last 25 years. Most of these studies have serious methodological failings that limit their usefulness, including the lack of routine fluoroscopic guidance for injections in any study published before 2000. During this same period, there have been 78 systematic reviews of ESIs, with divergent conclusions based on critical review of the same studies. Although isolated investigators have believed the data support the use of ESIs for specific populations, several more thorough reviews point to the limited or absent data on long-term pain relief or functional improvement associated with these procedures. The most recent Cochrane review on the subject takes issue with the entire spectrum of percutaneous spine procedures, concluding “there is insufficient evidence to support the use of injection therapy in subacute and chronic low-back pain.”

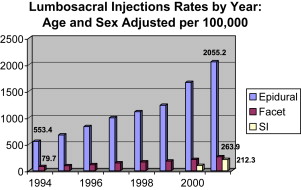

Despite the ambiguities in the data supporting ESIs, these procedures have developed widespread acceptance and are used with increasing frequency as a treatment of radiculopathy and other LBP disorders. In the United States, the use rates for ESIs of all types are escalating dramatically. In one analysis of Medicare claims from 1994 to 2001, there was a nearly 3-fold increase in ESI rates ( Fig. 2 ) and a 7-fold increase in subsequent reimbursed costs. These rates outpace the growth in the Medicare population in that time frame as well as the estimated increase in the prevalence of persons with LBP. Similar findings were noted in a study by Carrino and colleagues, also using Medicare claims data. The data from these studies do not offer insight into the cause of the increasing rates for ESIs, but this may be related to several possible factors such as expanding clinical usefulness, cultural changes, or socioeconomic issues.

The use of interventional spine procedures

Interventional spine procedures have been used for many decades for a variety of spinal disorders and range from percutaneous injections to surgery. For a variety of reasons, there has been a recent proliferation in the number of techniques available for use and marked increases in the use rates for many of the procedures. Percutaneous interventions include epidural steroid injections (ESIs) via several different approaches, facet/zygapophysial joint (z-joint) procedures, spinal cord stimulation, several intradiscal procedures, and, more recently, procedures intended to remove disc or other material in the spinal canal or to obtain segmental fusion. Surgical procedures range from well-established approaches for discectomy and/or spinal canal decompression to multiple means of addressing segmental fusion using several different approaches, materials, instruments, and indications. However, the evidence to support the use of many of these procedures is limited.

From the surgical perspective, there are sound data on the efficacy of discectomy for acute radicular pain associated with a disc herniation, decompressive laminectomy for symptomatic spinal stenosis, and fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis in well-selected patients. However, selecting appropriate candidates for surgery can be challenging because of variability in diagnosis and characterizing clinical and radiographic characteristics of these conditions. In addition, the clinical benefit of surgery even in well-selected patients can wane, and many patients may do just as well long-term with more conservative options. The data on the efficacy of surgery for isolated LBP are more suspect, and there are many additional patients in whom surgical procedures are either not indicated or contraindicated because of other issues. Surgical care also may carry significant risks and costs.

Because the role of surgery is limited for the larger population of patients with low back pain, there is a need for less invasive options. As noted earlier, several percutaneous procedures for spinal disorders have been developed and are frequently used clinically, most with limited scientific evidence of efficacy. The most commonly used and studied procedures of this type are ESIs, followed in frequency by z-joint procedures, which include intraarticular injections, medial branch blocks, and radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN). The use of each of these techniques has increased, and the evidence to support their use varies depending on the location in the spine (eg, cervical vs lumbar spine) as well as specific characteristics of the spinal disorder (eg, acute sciatica) and patient (eg, worker’s compensation status). The supportive evidence that is available for these procedures predominantly notes short-term improvements in pain. However, even in the best of circumstances the evidence for long-term benefit from any of these is lacking. To better understand the role of interventional care in the management of spinal pain, this review focuses on ESIs because similar trends and issues exist for the other procedures.

Epidural steroid injections

Although ESIs for the treatment of lumbosacral radicular pain were first introduced in the early 1950s, there has been a lot of interest recently in the use of these injections as an alternative to more invasive surgical procedures for treating spinal pain. Since the introduction pf ESIs, many investigators have examined them for the treatment of lumbosacral radiculopathy as well as axial (nonradicular) spinal pain syndromes. Although most studies have addressed the use of ESIs for isolated lumbosacral radiculopathy resulting from discogenic or other causes, some investigators have advocated their use for more diffuse symptoms associated with lumbar spinal stenosis. The current literature reports success rates of 18% to 90% for ESIs, depending on methodology, outcome measures, patient selection, and technique. Some studies, but not all, have found that ESIs can offer short-term pain reduction to a select group of patients, but there is little evidence of long-term improvement in pain or function. Given the overall spectrum of treatment approaches available for spinal pain, short-term pain relief can offer significant clinical benefits in appropriate circumstances, and this seems to be the primary beneficial effect of ESIs advocated by many investigators.

Several studies have attempted to examine the influence of ESIs on the subsequent need for lumbar surgery as an outcome measure. The results have been mixed. An initial prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Riew and colleagues reported that a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving transforaminal ESIs with anesthetic and corticosteroid opted not to have surgery compared with a control group receiving similar procedures with anesthetic alone. This study followed patients for up to 2 years after the first injection. However, in a separate report on 5-year follow-up of the same patients, there were no differences between the treatment and control groups in terms of lumbar surgery. A significant percentage of the treatment group was lost to follow-up for this study, making it difficult to draw any definitive conclusions from these data. A more recent study by Schaufele and colleagues in 2006 compared interlaminar versus transforaminal ESIs for persons with chronic LBP who had failed other conservative treatments. In this retrospective case-control study of 40 patients, the investigators found that 2 (10%) of the patients receiving transforaminal ESIs and 5 (25%) of the patients receiving interlaminar ESIs underwent subsequent lumbar surgery within 1 year after the initial injection. Follow-up beyond 1 year was not reported for these patients. Although the sample size in this study is small, this study is representative of the type of evidence available. Overall, the data indicating a significant effect of ESIs on surgical rates are not robust.

Some limited data are available on the cost-effectiveness of ESIs. Price and colleagues performed an RCT of ESIs in the United Kingdom and concluded that they did not meet the national guidelines for cost-effectiveness, specifically noting that “ESIs do not provide good value for money.” The investigators believed that further research is needed to compare alternative treatments for LBP and to identify subgroups of patients who might benefit more from ESIs. One drawback of this study is that it was performed in the United Kingdom, where there is a national health service, so it is unclear how applicable their cost analysis is to the US population. To date, there have been no cost-effectiveness studies of ESIs or other interventional pain procedures in the United States.

Regardless of which outcome is considered, one of the biggest challenges in interpreting the literature regarding the efficacy or effectiveness of ESIs is the paucity of high-quality RCTs. A recent survey of the published literature shows that there have been 18 RCTs of ESIs compared with placebo or control treatment for a variety of LBP conditions in the last 25 years. Most of these studies have serious methodological failings that limit their usefulness, including the lack of routine fluoroscopic guidance for injections in any study published before 2000. During this same period, there have been 78 systematic reviews of ESIs, with divergent conclusions based on critical review of the same studies. Although isolated investigators have believed the data support the use of ESIs for specific populations, several more thorough reviews point to the limited or absent data on long-term pain relief or functional improvement associated with these procedures. The most recent Cochrane review on the subject takes issue with the entire spectrum of percutaneous spine procedures, concluding “there is insufficient evidence to support the use of injection therapy in subacute and chronic low-back pain.”

Despite the ambiguities in the data supporting ESIs, these procedures have developed widespread acceptance and are used with increasing frequency as a treatment of radiculopathy and other LBP disorders. In the United States, the use rates for ESIs of all types are escalating dramatically. In one analysis of Medicare claims from 1994 to 2001, there was a nearly 3-fold increase in ESI rates ( Fig. 2 ) and a 7-fold increase in subsequent reimbursed costs. These rates outpace the growth in the Medicare population in that time frame as well as the estimated increase in the prevalence of persons with LBP. Similar findings were noted in a study by Carrino and colleagues, also using Medicare claims data. The data from these studies do not offer insight into the cause of the increasing rates for ESIs, but this may be related to several possible factors such as expanding clinical usefulness, cultural changes, or socioeconomic issues.

Understanding the increase in use

One of the more optimistic explanations available for the disproportionately escalating rate of ESI use could be improvements in health care delivery, including more effective management of spinal pain in the general population. If these improvements are occurring, improvements in measures of health or disability or a decrease in rates of surgical intervention for specific spine problems might be expected. The available data do not seem to indicate that this is the case. Paradoxically, measures of spine health in the United States show declines in recent years, and surgical rates for the treatment of degenerative spine problems have been dramatically increasing. When specifically looking at the effect of ESIs on surgical rates, Medicare claims data suggest that the performance of these procedures is positively associated with higher surgical rates rather than falling rates. In addition, epidemiologic studies have shown that the total number of people receiving ESIs who subsequently undergo lumbar surgery is increasing, as is the proportion of people undergoing surgery who have received ESIs. This particularly seems to be the case in areas of the country that have higher overall rates of injections. A study conducted using national Veteran’s Administration (VA) data on more than 13,000 individuals also showed that those who underwent more than 3 ESIs during a 2-year period were at increased risk of undergoing subsequent surgery compared with those who received 3 or fewer. Although none of these data indicate that performing ESIs increases surgical rates, they do not support the argument that ESIs (especially greater than 3 in the same patient) are substituting for lumbar surgery on a large-scale basis. Taken as an aggregate, these studies raise serious questions as to our ability to lower the need for surgery through the use of ESIs, which, along with pain reduction, is one of the prime benefits cited by many advocates of these procedures.

An additional surrogate measure to consider as an indicator of the broader health effect of ESIs is the use of opioid pain medications for those undergoing spinal procedures. As is the case with spinal injections and surgery, epidemiologic data indicate that opioid use in the United States is increasing at an alarming rate and that complications/deaths associated with opioid use (both prescribed and recreational/illicit use) are increasing. Although there are no data to indicate a causal relationship between the increase in interventional procedures for back pain and the use of opioid medications, one might hope that there would be evidence of a reduction in opiate use following ESIs. The data available are not supportive of this idea, either. An epidemiologic study performed within the VA system over a 2-year period showed no reduction in the use of opioids after ESI. Most people in this study were using opioids both before and after the intervention (64% vs 67%). This study did not determine the indication for the use of opioid medications in these patients and was not an RCT, both of which pose limitations on interpretation of the data. However, that there was no evidence of a reduction in opioid use raises the concern that in clinical practice the use of injections may not be associated with a significant decrease in opioid use as would be expected. When considered with the information on health status and surgical rates, the data make it difficult to argue that the expanding use of ESIs is accounting for major improvements in health outcomes.

Other explanations for the changes seen in use rates for ESIs may be found in more socioeconomic factors, such as alterations in the distribution and numbers of the providers who are performing the procedures. In the last 10 years, interventional pain management has blossomed, including a substantial increase in the number of fellowships offered (usually either anesthesiology or physical medicine and rehabilitation [PM&R]). The American Board of Pain Management began board certification in 2000. As of March 2009, more than 2200 physicians had been board certified by the American Board of Pain Medicine ( http://www.abpm.org/ ). This figure represents approximately 16% of the total number of providers board certified in PM&R and anesthesiology in the same period according to statistics from the American Board of Medical Specialties. In one study on geographic variations of ESI use, ESI rates strongly correlated with the number of providers performing these procedures in a given area ( r = 0.79, P <.001), suggesting that the supply of physicians who perform injections may be a significant factor in the increase in ESI use. The influx of specialists board certified in interventional pain care and the increasing role of PM&R in interventional spine care could thus be major contributors to the increase in interventional pain procedures being performed. Some have argued that board certification programs and improved training in pain management have led to improvements in the quality of care provided for persons suffering from chronic pain and that the increase in the number of procedures being performed is partially in response to a previously unmet need. However, given the foregoing discussion it has yet to be shown that the increase in supply of board-certified physicians and the treatments provided has made a substantial difference in the functioning, quality of life, or pain levels of people with chronic LBP.

Another socioeconomic issue potentially affecting the use of ESIs is the growth of physician-owned ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) in the United States. ASCs are freestanding facilities designed specifically for outpatient surgical procedures that do not require an overnight or inpatient hospital admission. The number of Medicare-certified ASCs increased by more than 60% from 2000 to 2007, totaling nearly 5000 across the United States. During this time, Medicare payments for services provided at ASCs more than doubled, from $1.4 billion to $2.9 billion. Ninety-five percent of Medicare-certified ASCs are privately owned, for-profit businesses, most of which are owned by local physician investors. The Stark self-referral law, established in 1989 to ensure that economic conflicts of interest do not drive up use, does not apply to ASCs, making it possible for physicians to refer their own patients to the ASCs with which they may have financial relationships. By delivering care in these centers, physician investors can increase practice revenues by receiving facility fees that often are larger than the professional fees they receive for the procedures. This type of arrangement may affect physician behavior by creating financial conflicts of interest for physicians practicing in ASCs and potentially increase use rates for various forms of interventional care. In support of this concept, there are data on imaging and spine surgery rates to suggest that financial incentives associated with physician-owned facilities may alter physician practice patterns.

In addition to financial interests, there are several legitimate potential reasons why a variety of procedures may be performed in ASCs as opposed to other locations such as hospitals and physician offices. Included in these reasons are the possibility of improved outcomes related to specialized staffing, more efficient protocols, dedicated equipment, better customer service, and the presence of more convenient locations with shorter wait times than hospital settings. Although the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) examines cost and use trends to determine the appropriate reimbursement for procedures performed at ASCs, there have been few published data comparing outcomes for procedures performed in these settings with those in more traditional hospital settings and none examining interventional pain procedures for back pain.

These issues are of concern because, although interventional spine procedures can be performed in physician offices, ASCs, or outpatient hospital settings, there are some data to suggest that an increasing percentage are being performed at ASCs. ESIs are one of the most frequently performed procedures at ASCs, outpaced only by colonoscopies/endoscopies and cataract surgeries. This situation may be related to increased physician reimbursement for procedures performed at these sites compared with offices or outpatient hospitals, particularly when accounting for facility fees captured by physician ASC owners as dividends. These data leave open the idea that financial incentives for providers performing ESIs in physician-owned facilities may be a significant driver of use rates.

When looking at the totality of the published data on ESIs, a concern is that the increase in their use is more related to economic factors than to clinical ones. Although the rates of ESIs and other interventional spine procedures are expanding rapidly, there is no evidence of broad societal or clinical benefits. There is some literature indicating short-term improvements in pain after ESIs, but the literature base is replete with numerous systematic reviews built on a paucity of well-designed RCTs. More data are needed on indications, patient selection, frequency, route of administration, and cost-effectiveness to establish the true clinical usefulness of these procedures. Considering the state of the literature alongside the societal need and desire to use nonsurgical treatment options and the economic factors related to physician supply and reimbursement, it becomes difficult to argue that the primary impetus behind the recent increased use of ESIs and other spinal procedures is clinical usefulness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree