Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases

Glenn T. Furuta

Peter Ngo

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases are clinicopathologic entities requiring a mucosal biopsy for diagnosis. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis, the classical eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease, presents with a broad range of symptoms, with mucosal biopsies revealing eosinophilic inflammation of the stomach and small bowel. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the location of eosinophilic infiltration but can include abdominal pain, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, and failure to thrive. Exclusion of other causes of gastrointestinal eosinophilia such as drug reactions, parasitic infections, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and inflammatory bowel disease is required to make the diagnosis. The cause of eosinophilic gastrointestinal

disorders is unclear, but several lines of evidence implicate allergy as a primary cause. The last decade has witnessed a dramatic rise in the recognition and incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis (EE). EE occurs more commonly than does eosinophilic gastroenteritis and has better defined features.

disorders is unclear, but several lines of evidence implicate allergy as a primary cause. The last decade has witnessed a dramatic rise in the recognition and incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis (EE). EE occurs more commonly than does eosinophilic gastroenteritis and has better defined features.

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

Pathogenesis

Increasing evidence supports the concept that EE is related to an allergic response. Between 33% and 100% of affected patients have atopic disease or peripheral eosinophilia. The affected esophageal mucosa demonstrates increased expression of interleukin (IL)-5, an eosinophiliotropic cytokine. Specific antigens initiating the inflammatory cascade are likely unique to the individual, but food and aeroallergens are suspected. Mechanisms of the allergic response are not certain; some patients have elevated IgE, whereas others do not. Dysphagia and predisposition for food impaction are thought to be due to either esophageal dysmotility or proximal esophageal strictures. Esophageal motility studies document increased ineffective contractions. Endoscopic ultrasonic evaluation revealed thickening of mucosal, submucosal, and muscularis layers of the esophagus, suggesting muscular involvement.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms associated with EE can be very similar to those observed in GERD and include vomiting, dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain, epigastric pain, nausea, aversive feeding behavior, failure to thrive, or respiratory symptoms such as coughing and wheezing. In contrast to children with GERD, patients with EE do not have a clinical response to acid blockade. The most characteristic symptom of EE is dysphagia, which often is accompanied by food impaction. Not all children with EE will report these symptoms, thus mandating a high level of suspicion.

Diagnosis

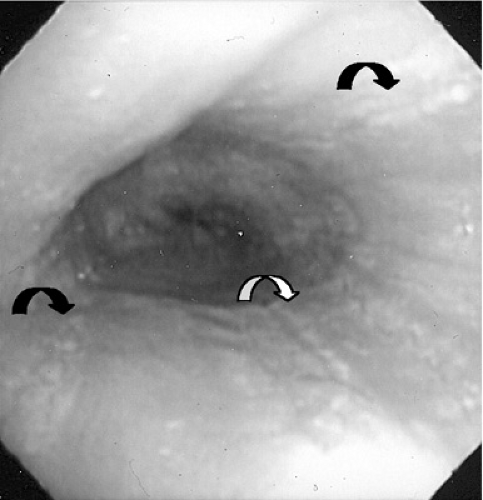

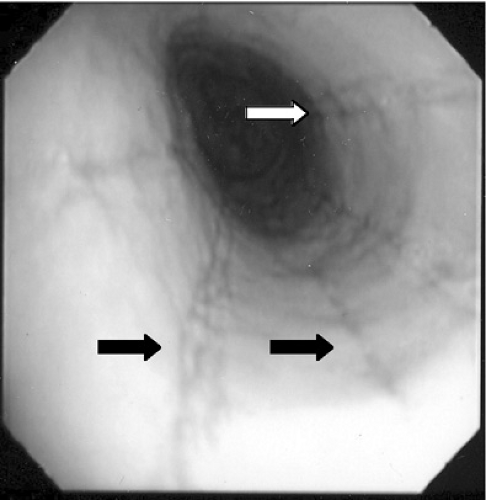

Histologic evaluation of esophageal tissue is the cornerstone of diagnosis. When symptoms are unresponsive to acid blockade, upper endoscopy with mucosal biopsy is indicated. The healthy esophageal mucosa is devoid of eosinophils, whereas in patients with EE, greater than 15 to 20 eosinophils per high power field are seen on light microscopy. The proximal as well as the distal esophagus can be involved, and eosinophilic aggregates or microabscesses often are present. A speckled pattern of pinpoint white papules, which appears similar to Candida infection, actually represents these superficial eosinophilic microabscesses (Fig. 358.1). Other gross endoscopic findings include mucosal furrowing (linear folds along the esophageal mucosa), concentric rings in the esophageal wall, and proximal strictures (Fig. 358.2). pH monitoring of the distal esophagus typically is normal.

Therapy

Consistent with the hypothesis that food allergens provide antigenic stimuli for eosinophilic inflammation, studies have shown convincingly that elemental diets and targeted dietary elimination can result in clinical and histologic resolution. Consultation with an allergist is recommended and may identify a specific allergen via skin prick, radioallergosorbent (RAST), or skin patch testing. If dietary elimination does not produce satisfactory results, immunosuppression with corticosteroids should be considered. Although systemic corticosteroids can produce clinical and histologic improvement, they are associated with undesirable side effects. To decrease these effects, topical application of corticosteroids have been used and shown to be effective in several studies. Aerosolized corticosteroids such as fluticasone propionate delivered via a metered-dose canister can provide a topical coating of corticosteroid if the medication is swallowed instead of inhaled.

Prognosis

Although the natural history of EE has not been studied well, it appears to have a chronic course requiring prolonged treatment similar to that for allergic asthma. Adult studies document the presence of proximal esophageal strictures, but Barrett esophagus or metaplasia has not been reported.

EOSINOPHILIC GASTROENTERITIS

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of eosinophilic gastroenteritis is unknown. Between 20% and 70% of affected patients have an atopic disease suggesting an allergic contribution. Affected gastrointestinal tissues show evidence of cytokines intimately involved in the growth, maturation, and activation of eosinophils. The duodenal and colonic tissues from nine of ten affected patients demonstrated immunohistochemical staining for IL-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. The tissues that did not show evidence of these cytokines came from a patient who had undergone treatment with corticosteroids. Interestingly, the serum level of IL-5 was undetectable in all patients examined, suggesting that the intestinal immunologic milieu provides a compartment that is separate from the systemic and is conducive to eosinophil growth and proliferation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree