Elbow and Wrist Elbow Arthroscopy: The Basics

John E. Conway

DEFINITION

Elbow arthroscopy involves the use of an arthroscope to examine the interior of the elbow joint and provides the opportunity to perform minimally invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

Elbow arthroscopy has evolved to allow the definitive care of more than a dozen complex elbow conditions.

Despite an expanded understanding of the surrounding neurovascular anatomy, essential portal placement for access to the elbow joint continues to present a level of risk for injury that exceeds that seen in other joints.4,6,7,14

The safe application of this treatment modality requires that the surgeon have a solid grasp of the relative anatomy, fellowship or laboratory training in treatment techniques, experience as an arthroscopist, and an objective assessment of his or her own level of skill.

ANATOMY

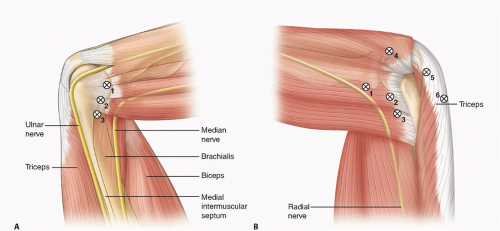

Neurovascular injury risk is relatively high and a three-dimensional grasp of elbow anatomy is essential for safe and successful elbow arthroscopy (FIG 1).1,3,5,6,7,8,10,11,12,15

Miller et al8 showed that the bone-to-nerve distances in the 90-degree-flexed elbow increased with joint insufflation an average of 12 mm for the median nerve, 6 mm for the radial nerve, and 1 mm for the ulnar nerve.

The capsule-to-nerve distance changes very little with insufflation, however, and the protective effect of insufflation is lost when the elbow is in extension.

Miller et al8 also showed that in the insufflated, 90-degree-flexed elbow, both the radial and median nerves passed within 6 mm of the joint capsule and that the radial nerve was on average 3 mm closer to the capsule than the median nerve. The ulnar nerve was essentially on the capsule.

Stothers et al11 emphasized the importance of elbow flexion during portal placement and showed that the portal-to-nerve distances decreased an average of 3.5 to 5.1 mm laterally and 1.4 to 5.6 mm medially when the elbow was in extension.

For the distal anterolateral portal, the distance from the sheath to the radial nerve averaged 1.4 mm (range 0 to 4 mm) in extension and 4.9 mm (2 to 10 mm) in flexion.

Field et al3 compared three anterolateral portals and reported a statistically significant difference in portal-to-radial nerve distance, with greater safety shown with the more proximal locations.

Anatomic studies suggest three guidelines for neurovascular safety:

Portal placement is safer when the elbow is flexed 90 degrees than when it is in extension.11

Maximal joint distention before portal placement increases the safety during placement by increasing the nerve-toportal distance.3,5,6,11

The nerve-to-portal distance is greater for the more proximal anterior portals than for the more distal anterior portals.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

This chapter does not address a specific condition but instead offers a broad view of the basic considerations and setup issues for a surgical treatment that may be applied to many different elbow problems.

A complete review of the numerous clinical tests described for the diagnostic evaluation of the elbow would exceed the scope of this chapter.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Routine preoperative elbow radiographs should include a true lateral view, a standard anteroposterior (AP) view, and an AP view of both the distal humerus and proximal forearm when joint motion loss prevents full joint extension.

Additional radiographic views include the cubital tunnel view, the posterior impingement view, the capitellum view, and the radial head view.

The cubital tunnel view, an AP projection of the humerus with the elbow maximally flexed, provides a clear view of the medial epicondyle and cubital tunnel groove.

The posterior impingement view is also an AP projection of the humerus with the elbow maximally flexed, but the humerus is rotated into 45 degrees of external rotation. This image offers better assessment of the posteromedial edge of the olecranon tip and the medial epicondyle apophysis.

The capitellum view, an AP projection of the ulna with the elbow flexed 45 degrees, provides a tangential view of the capitellum for better evaluation of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesions.

The radial head view is an oblique view of the 90-degree-flexed elbow with the beam passing between the ulna and the radial head. It allows for clear imaging of both the radial head and the radial-ulna interval.

Although this point is sometimes argued, computed tomography is often useful when resection of intra-articular bone is considered as a part of contracture release arthroscopy.

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging in a closed high-field magnet with thin-section, optimized, high-spatial-resolution sequences may provide exceptional detail of the structures surrounding the elbow joint; however, MR arthrography, with either saline or gadolinium, will improve the assessment of intra-articular structures such as loose bodies.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The indications for elbow arthroscopy include the evaluation and treatment of septic arthritis, lateral synovial plica syndrome, systemic inflammatory arthritis, loose bodies, synovitis, OCD, degenerative arthritis, posterior impingement, traumatic arthritis, trochlea chondromalacia, arthrofibrosis, lateral epicondylitis, joint contracture, posterolateral rotatory instability, and olecranon bursitis.

Treatment options for these conditions include diagnostic evaluation, loose body removal, synovial biopsy, partial or complete synovectomy, plica excision, extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon débridement, capsule release, capsulotomy, capsulectomy, exostosis excision, ulnohumeral arthroplasty, contracture release, chondroplasty, microfracture chondroplasty, percutaneous drilling or fixation of OCD lesions, capitellum osteochondral transplantation, radial head excision, internal fixation of fractures, lateral ulnar collateral ligament plication, ulnar nerve decompression, and finally, olecranon bursoscopy and bursectomy.

The relative contraindications for elbow arthroscopy include recent joint or soft tissue infection; developmental changes; previous trauma or surgery that significantly alters the normal neurovascular, bony, or soft tissue anatomy of the elbow; extensive extracapsular heterotopic ossification; complex regional pain syndrome; and conditions that prevent distention of the elbow capsule.

Previous ulnar nerve transposition usually requires exposure of the ulnar nerve before the creation of an anteromedial portal.

Preoperative Planning

As with all medical conditions, the importance of the information gained from a careful and complete history and examination for establishing an accurate diagnosis cannot be overemphasized.

Plain radiographs are also essential, but some authors suggest that computed tomography and MR imaging offer little in the preoperative assessment.

In contrast, the exact location of intra-articular, capsular, and extra-articular bone; the thickness of the joint capsule; the integrity of the cartilage covering an OCD lesion; and the presence of stress fractures or loose bodies unseen on radiographs are a few examples of how additional imaging may direct or modify care.

The surgeon should consider how associated procedures to be performed in conjunction with the arthroscopy will affect patient positioning and the possible need to reposition during the case.

Fluoroscopy should be available when drilling, pinning, or internal fixation is considered.

In addition to standard arthroscopic instrumentation, the preoperative plan should also consider the need for specialized instruments such as retractors and special biters for contracture release surgery and small fragment fixation devices for OCD or fracture care.

Elbow arthroscopy may be done using either general or regional anesthesia.

General anesthesia is typically preferred as it allows for complete muscle relaxation. Regional blockade is reserved for contracture release procedures where repeated manipulation and continuous passive motion is planned during the hospitalization.

Although regional anesthesia may be given before surgery, many surgeons prefer to wait until the status of the neurovascular structures is established in the recovery setting.

Indwelling catheter regional anesthesia is described and sometimes recommended for contracture release procedures, but not all centers are comfortable or experienced

with these techniques, and repeated regional anesthesia during the hospitalization appears to be equally effective.

The use of ultrasound during injection may decrease the morbidity associated with regional anesthesia.

Positioning

The four patient positions for elbow arthroscopy are the supine cross-body position, the supine suspended position, the lateral decubitus position, and the prone position.

Although the latter two positions are most popular today, experience with one of the supine positions still offers advantages. For example, a surgeon who prefers the prone position may elect to use the supine cross-body position when arthroscopic and open procedures are combined, preventing the need for repositioning.

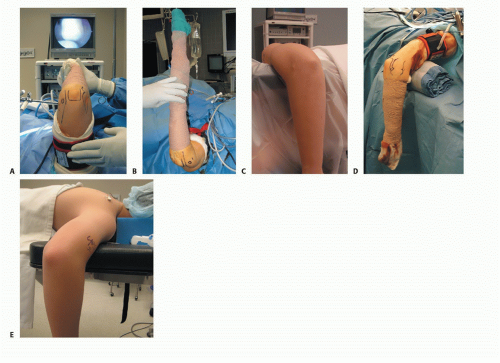

Supine cross-body position

Arthroscopy in this position may be done with one of several commercially available arm-holding devices but is performed equally well with an assistant acting as the arm holder (FIG 2A).

Because the elbow is not rigidly stabilized in this position, complex procedures may be more challenging and present a greater level of risk for injury.

The supine cross-body position is a safe and effective position for elbow arthroscopy regardless of the complexity of the procedure and provides the opportunity to convert to either an open cross-body approach or an open abductedon-arm board approach.

Supine suspended position

This position requires the use of a traction device from which the arm is hung. Capture of the hand or wrist is necessary, and finger traps on the index and long fingers work well in this regard (FIG 2B).

The elbow is not stabilized against either a post or pad, which allows considerable movement of the elbow beneath the hand.

Two potential disadvantages of this position are the unexpected withdrawal of the arthroscope from the freely swinging joint and the almost vertical position of the arthroscope during arthroscopy of the posterior compartment.

Lateral decubitus position

This position for elbow arthroscopy is typically set up the same as for shoulder surgery except that the arm is draped across a padded horizontal post attached to the table (FIG 2C).

The advantage of this position over the supine positions is that a stable platform is created on which the upper arm rests. There is equal access to the anterior and posterior compartments.

The advantage of this position over the prone position becomes apparent when management of the airway is at issue. If prone positioning is a concern, such as in patients with a high body mass index or compromised lung

volume, the case is probably best done in the lateral decubitus position.

One disadvantage of this position is that small patients, such as gymnasts with OCD lesions, are difficult to position laterally and still maintain full access to the arm.

Prone position

Many surgeons, because of the stability and access provided, prefer the prone position. However, careful attention to positioning is essential to avoiding complications (FIG 2D).

The airway must be secure and the face should be well padded.

Chest rolls are used to lift the chest and abdomen from the table, decreasing the airway pressure required for ventilation.

The knees are padded and the feet are elevated.

The nonoperative arm is placed on a well-padded arm board, with attention to the ulnar nerve, and the operative arm is allowed to hang over a shortened, padded arm board positioned along the side of the table (FIG 2E).

Pulses in all four extremities are confirmed.

After draping, a small roll of towels is placed beneath the upper arm to align the humerus in the coronal plane of the body and to allow the elbow to flex to 90 degrees.

Approach

The first arthroscopic portal is anterior except when the entire procedure is accomplished through posterior portals. Occult conditions may exist in the anterior compartment, and a complete diagnostic assessment of the joint requires anterior portals.

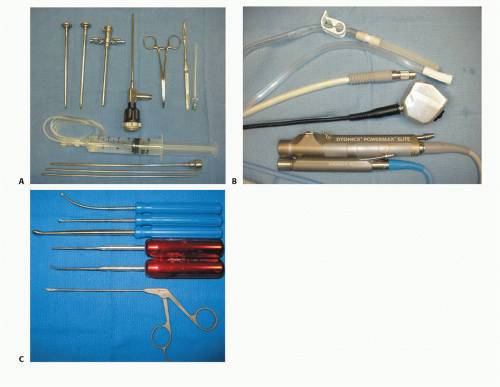

FIG 3 • A,B. Basic instruments used in elbow arthroscopy. A. A standard 4.0-mm, 30-degree offset arthroscope, an arthroscope sheath with sharp and dull trocars, an 18-gauge spinal needle, a 60-mL saline in large syringe with connector tubing, a hemostat, a Wissinger rod, and switching rods. B. A standard mechanical shaver, a mini mechanical shaver, an arthroscope camera, a light cord, inflow tubing, and suction tubing. C. Specialized instruments for elbow arthroscopy: a hand biter and curved and straight arthroscopic retractors, curettes, awls, and osteotomes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access