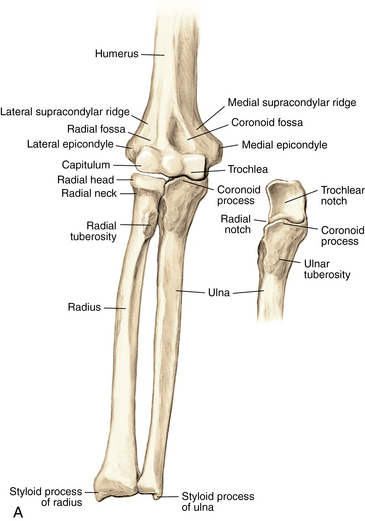

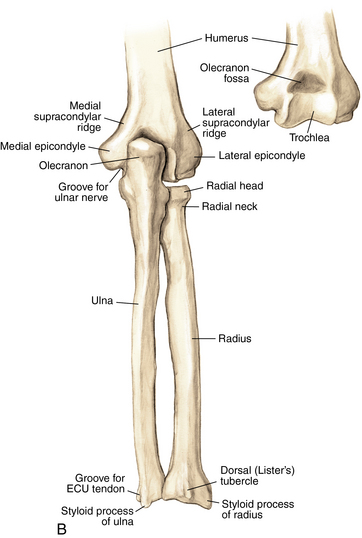

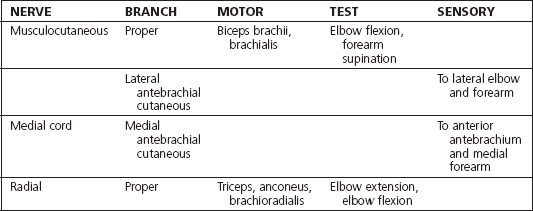

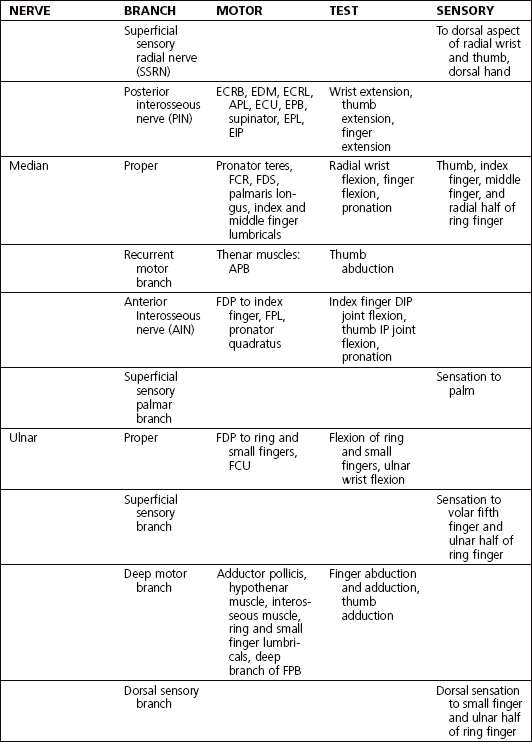

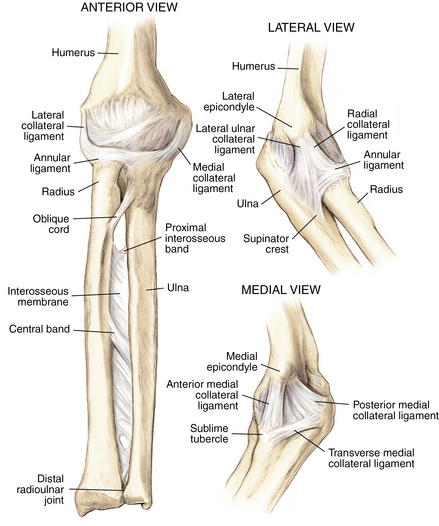

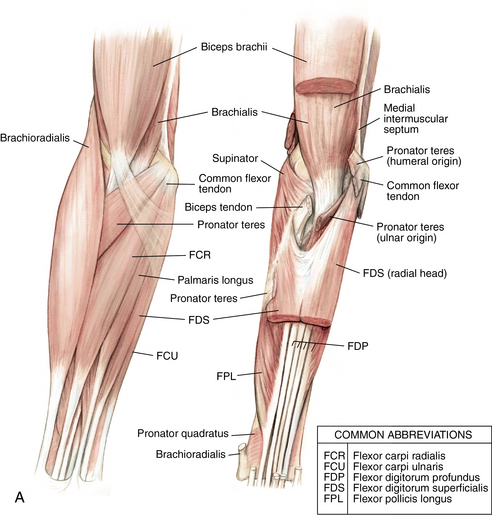

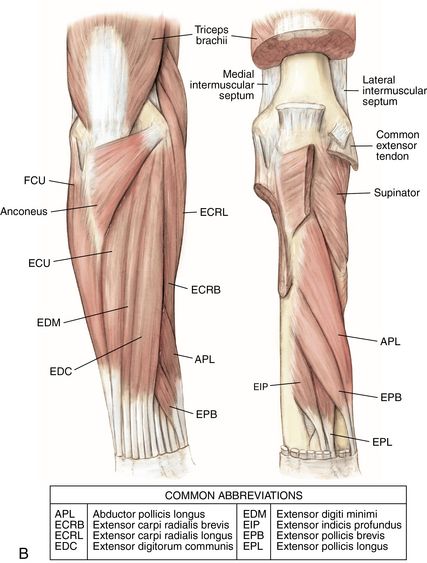

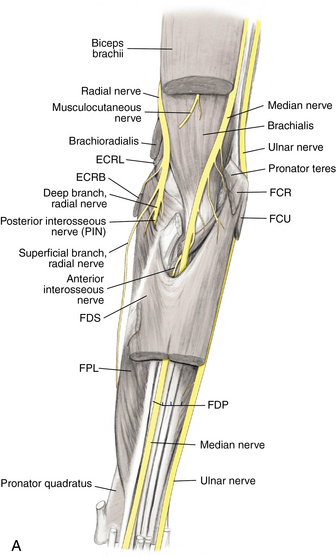

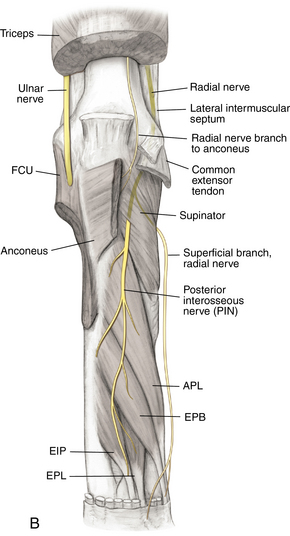

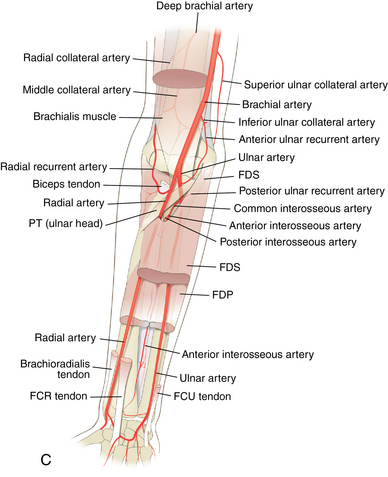

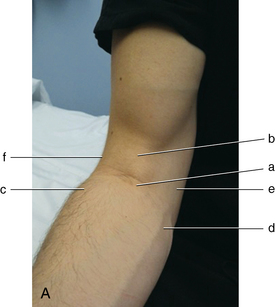

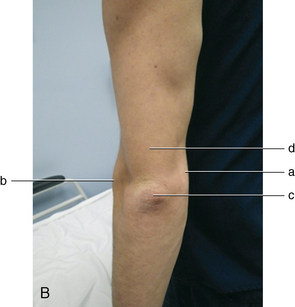

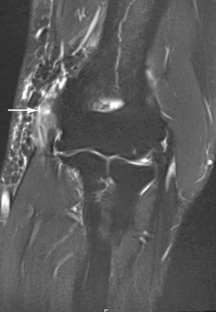

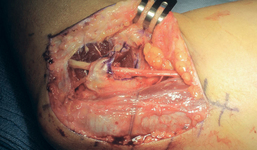

3 Elbow and forearm Figure 3-2. Ligaments of the elbow and forearm. Components of the elbow ligaments—ulnar collateral ligament: anterior band, posterior band, and transverse band; lateral collateral ligament: annular ligament, radial collateral ligament, accessory collateral ligament, and lateral ulnar collateral ligament. (From Chhabra AB: Elbow and forearm. In Miller MD, Chhabra AB, Hurwitz S, et al, editors: Orthopaedic surgical approaches, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders, p 67.) Figure 3-3. A, Muscles and tendons of the anterior elbow and forearm: superficial and deep compartments. B, Muscles and tendons of the posterior elbow and forearm: superficial and deep compartments. (From Chhabra AB: Elbow and forearm. In Miller MD, Chhabra AB, Hurwitz S, et al, editors: Orthopaedic surgical approaches, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders, pp 68, 69.) Figure 3-4. A, Anterior view of the nerves of the elbow and forearm. B, Posterior view of the nerves of the elbow and forearm. C, Arteries of the elbow and forearm. APL, abductor pollicis longus; ECRB, extensor carpi radialis brevis; ECRL, extensor carpi radialis longus; EIP, extensor indicis profundus; EPB, extensor pollicis brevis; EPL, extensor pollicis longus; FCR, flexor carpi radialis; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; FDP, flexor digitorum profundus; FDS, flexor digitorum superficialis; FPL, flexor pollicis longus; PT, pronator teres. (From Chhabra AB: Elbow and forearm. In Miller MD, Chhabra AB, Hurwitz S, et al, editors: Orthopaedic surgical approaches, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders, pp 74, 75, 81.) Figure 3-5. Surface anatomy of the anterior and posterior elbow and forearm. A, Anterior labels: a) antebrachial fossa, b) biceps tendon, c) common extensor tendons, d) common flexor tendons, e) medial epicondyle, f) lateral epicondyle. B, Posterior labels: a) medial epicondyle, b) lateral epicondyle, c) olecranon process, d) triceps tendon. Inspect for edema, deformity, ecchymosis, biceps muscle. Table 3-2. Normal Elbow and Forearm Range of Motion Table 3-4. Differential Diagnosis of Elbow Pain Figure 3-8. Magnetic resonance image of lateral epicondylitis. Edema and high-grade partial tearing of the common extensor tendon origin are visible (arrow). • Perform a wound check and suture removal. • Therapy: Start therapy for gentle elbow ROM. The patient should avoid lifting with the operative extremity. • Perform a motion check. Evaluate and document whether the patient has tenderness to palpation at the lateral epicondyle. Figure 3-9. Magnetic resonance image of medial epicondylitis. Edema and high-grade partial tearing of the common flexor tendon origin are visible (arrow). Medial epicondylitis is also known as golfer’s elbow and is a form of tendinitis. It is an inflammatory condition, and treatment revolves around decreasing the inflammation and strengthening the musculature. Because the tendons that are inflamed are responsible for wrist flexion and pronation, the pain is occasionally worse with gripping, lifting, and twisting. • Perform a wound check and suture removal. • Therapy: Start gentle elbow ROM. The patient is to avoid lifting with the operative extremity. • Perform a motion check. Evaluate and document whether the patient has tenderness to palpation at the medial epicondyle. Figure 3-12. Intraoperative photograph of a transposed ulnar nerve. The nerve now lies anterior to the medial epicondyle and is held in place by lengthened flexor-pronator fascia. • Some clinicians advocate for an early therapy session for gentle elbow ROM and edema control to prevent stiffness. A removable thermoplastic long-arm posterior splint may be fabricated to support the arm between therapy sessions. • Sutures are removed, and ROM is assessed. • Inquire about and document changes in preoperative paresthesias. • Perform a wound check, and evaluate for hypersensitivity. • Inquire about and document changes in preoperative paresthesias. • Check and document Froment and Wartenburg signs. • The patient can start strengthening exercises between 6 and 8 weeks and gradually return to everyday activities without restrictions. Olecranon bursitis is a condition of inflammation or infection of the olecranon bursa. It can occur from repetitive leaning on the elbow or from mild trauma. The bursa can be filled with sterile serous fluid or infection. Recurrences are possible and may require repeat aspiration, but nonoperative treatment is successful most of the time. If the bursitis is mild and clinically deemed to be aseptic, avoid aspiration, to reduce the risk of iatrogenic infection.

Anatomy

Ligaments: Figure 3-2

Muscles and tendons: Figure 3-3

Nerves and arteries: Figure 3-4 and table 3-1

Surface anatomy: Figure 3-5

Physical examination (table 3-2, 3-3, 3-4)

Extension

0 degrees

Flexion

135 degrees

Supination

90 degrees

Pronation

90 degrees

Medial-sided elbow pain

Medial epicondylitis

Ulnar collateral ligament injury

Arthritis

Cubital tunnel syndrome

Lateral-sided elbow pain

Lateral epicondylitis

Radial head fracture

Lateral collateral ligament injury

Anterior elbow pain

Biceps tendinitis or biceps tendon rupture

Posterior elbow pain

Olecranon bursitis

Triceps tendinitis

Forearm pain

Radial tunnel syndrome

Muscle strain

Lateral epicondylitis

Imaging: Figure 3-8

Initial treatment

First treatment steps

Patient education and activity modification are paramount to successful treatment.

Patient education and activity modification are paramount to successful treatment.

Good results are reported in the literature after 12 months of conservative management.

Good results are reported in the literature after 12 months of conservative management.

Measures include avoidance of aggravating activities and repetitive lifting and gripping, correction of improper lifting or gripping techniques, a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) regimen if tolerated, possible use of transdermal anesthetic patches, heat and ice modalities with stretching, and occupational therapy referral.

Measures include avoidance of aggravating activities and repetitive lifting and gripping, correction of improper lifting or gripping techniques, a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) regimen if tolerated, possible use of transdermal anesthetic patches, heat and ice modalities with stretching, and occupational therapy referral.

Some advocate use of a wrist brace to limit wrist extension during activities.

Some advocate use of a wrist brace to limit wrist extension during activities.

Treatment options

Conservative management is reserved for patients with no previous treatment or whose previous treatment was successful but the problem recurred after several months or years.

Conservative management is reserved for patients with no previous treatment or whose previous treatment was successful but the problem recurred after several months or years.

In addition to initial treatments listed earlier, a cortisone injection may be performed (see p. 107 for lateral epicondyle injection).

In addition to initial treatments listed earlier, a cortisone injection may be performed (see p. 107 for lateral epicondyle injection).

Avoid multiple repeat injections over a short time because they can result in local tissue destruction and possible tendon or ligament rupture.

Avoid multiple repeat injections over a short time because they can result in local tissue destruction and possible tendon or ligament rupture.

Advise the patient on a period of rest and activity modification after injection.

Advise the patient on a period of rest and activity modification after injection.

If referring patient to occupational therapy, the referral should include instructions to provide elbow stretching, gradual protected strengthening, counseling on lifting techniques, and use of local modalities for inflammation.

If referring patient to occupational therapy, the referral should include instructions to provide elbow stretching, gradual protected strengthening, counseling on lifting techniques, and use of local modalities for inflammation.

If the patient notes no improvement or diminishing improvement in symptoms with injections, consider an MRI scan to evaluate for any other causes of lateral elbow pain such as an LCL injury. Lateral epicondylitis may be described on an MRI as “high-grade partial tearing of the common extensor tendon origin.”

If the patient notes no improvement or diminishing improvement in symptoms with injections, consider an MRI scan to evaluate for any other causes of lateral elbow pain such as an LCL injury. Lateral epicondylitis may be described on an MRI as “high-grade partial tearing of the common extensor tendon origin.”

Interest in the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections is increasing, but no definitive data on its efficacy are available, and this treatment is still considered experimental.

Interest in the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections is increasing, but no definitive data on its efficacy are available, and this treatment is still considered experimental.

Operative management

Informed consent and counseling

Surgical débridement has shown good results in the literature, but the risk of partial or no relief of symptoms is approximately 15%.

Surgical débridement has shown good results in the literature, but the risk of partial or no relief of symptoms is approximately 15%.

The surgical procedure is not likely to be successful if the patient fails to modify activities or cease repetitive trauma postoperatively.

The surgical procedure is not likely to be successful if the patient fails to modify activities or cease repetitive trauma postoperatively.

The patient will require a 2- to 3-month recovery period with monitored progressive occupational therapy.

The patient will require a 2- to 3-month recovery period with monitored progressive occupational therapy.

Surgical procedures

Lateral epicondyle débridement

An oblique incision is made just anterior to the lateral epicondyle and common extensor tendon origin. Care is taken to avoid injury to the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve.

An oblique incision is made just anterior to the lateral epicondyle and common extensor tendon origin. Care is taken to avoid injury to the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve.

The lateral epicondyle is identified, and a split is made in the common extensor tendon origin parallel to the fibers. The tissue is divided in layers until the underlying joint capsule is identified.

The lateral epicondyle is identified, and a split is made in the common extensor tendon origin parallel to the fibers. The tissue is divided in layers until the underlying joint capsule is identified.

A rongeur or curette is used to débride the dysvascular tissue and to stimulate bleeding. Avoid injury to the underlying LCL. Sometimes, a Kirschner wire (K-wire) is used to puncture the lateral epicondyle several times and stimulate bleeding at the origin of the tendon.

A rongeur or curette is used to débride the dysvascular tissue and to stimulate bleeding. Avoid injury to the underlying LCL. Sometimes, a Kirschner wire (K-wire) is used to puncture the lateral epicondyle several times and stimulate bleeding at the origin of the tendon.

Once débridement has concluded, the common extensor tendon is repaired in layers using a suture. The fascia is also closed followed by the subcutaneous tissues and the skin. Most surgeons immobilize the patient in a long-arm posterior splint for 10 to 14 days.

Once débridement has concluded, the common extensor tendon is repaired in layers using a suture. The fascia is also closed followed by the subcutaneous tissues and the skin. Most surgeons immobilize the patient in a long-arm posterior splint for 10 to 14 days.

Estimated postoperative course

Medial epicondylitis

Definition: tendinitis of the common flexor tendon origin, also known as golfer’s elbow

Definition: tendinitis of the common flexor tendon origin, also known as golfer’s elbow

Possible reported history of injury or repetitive trauma

Possible reported history of injury or repetitive trauma

Possible patient-reported associated paresthesias in the fourth and fifth fingers (possible simultaneous cubital tunnel syndrome resulting from inflammation)

Possible patient-reported associated paresthesias in the fourth and fifth fingers (possible simultaneous cubital tunnel syndrome resulting from inflammation)

Physical examination

Possible mild edema over medial epicondyle

Possible mild edema over medial epicondyle

Point tenderness to palpation over medial epicondyle

Point tenderness to palpation over medial epicondyle

Pain with resisted wrist flexion

Pain with resisted wrist flexion

Elbow stable to stress testing of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL)

Elbow stable to stress testing of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL)

Evaluation of the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel for subluxation or neuritis (see p. 84 for cubital tunnel syndrome)

Evaluation of the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel for subluxation or neuritis (see p. 84 for cubital tunnel syndrome)

Imaging: Figure 3-9

Initial treatment

First treatment steps

Patient education and activity modification are paramount to successful treatment.

Patient education and activity modification are paramount to successful treatment.

Measures include avoidance of aggravating activities and repetitive activities, correction of improper techniques, NSAID regimen if tolerated, heat and ice modalities with stretching, and occupational therapy referral.

Measures include avoidance of aggravating activities and repetitive activities, correction of improper techniques, NSAID regimen if tolerated, heat and ice modalities with stretching, and occupational therapy referral.

Some advocate use of a wrist brace to limit wrist flexion during activities.

Some advocate use of a wrist brace to limit wrist flexion during activities.

If fourth and fifth finger paresthesias are present, consider obtaining an electromyography and nerve conduction study (EMG/NCS) to evaluate for concomitant cubital tunnel syndrome.

If fourth and fifth finger paresthesias are present, consider obtaining an electromyography and nerve conduction study (EMG/NCS) to evaluate for concomitant cubital tunnel syndrome.

Treatment options

Conservative management is reserved for patients with no previous treatment or whose previous treatment was successful but the problem recurred after several months or years.

Conservative management is reserved for patients with no previous treatment or whose previous treatment was successful but the problem recurred after several months or years.

In addition to initial treatments listed earlier, a cortisone injection may be performed (see p. 108 for medial epicondyle injection).

In addition to initial treatments listed earlier, a cortisone injection may be performed (see p. 108 for medial epicondyle injection).

Avoid multiple repeat injections over a short time because this can result in local tissue destruction and possible tendon or ligament rupture.

Avoid multiple repeat injections over a short time because this can result in local tissue destruction and possible tendon or ligament rupture.

A relative contraindication to injection is a subluxating ulnar nerve.

A relative contraindication to injection is a subluxating ulnar nerve.

Advise the patient on a period of rest and activity modification after injection.

Advise the patient on a period of rest and activity modification after injection.

If referring the patient to occupational therapy, the referral should include instructions to provide elbow stretching, gradual protected flexor-pronator strengthening, and use of local modalities for inflammation.

If referring the patient to occupational therapy, the referral should include instructions to provide elbow stretching, gradual protected flexor-pronator strengthening, and use of local modalities for inflammation.

If the patient notes no improvement or diminishing improvement in symptoms with injections, consider an MRI scan to evaluate for any other causes of medial elbow pain such as a UCL injury.

If the patient notes no improvement or diminishing improvement in symptoms with injections, consider an MRI scan to evaluate for any other causes of medial elbow pain such as a UCL injury.

Surgical procedures

The medial approach is used for tendon débridement.

The medial approach is used for tendon débridement.

If cubital tunnel syndrome is present, an ulnar nerve transposition can be performed simultaneously with this procedure (see p. 84 for cubital tunnel syndrome).

If cubital tunnel syndrome is present, an ulnar nerve transposition can be performed simultaneously with this procedure (see p. 84 for cubital tunnel syndrome).

Medial epicondyle débridement

An oblique incision is made just anterior to the medial epicondyle. Care is taken to avoid injury to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel.

An oblique incision is made just anterior to the medial epicondyle. Care is taken to avoid injury to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel.

The medial epicondyle is identified, and a split is made in the common flexor tendon origin parallel to the fibers. The tissue is divided in layers until the underlying joint capsule is identified.

The medial epicondyle is identified, and a split is made in the common flexor tendon origin parallel to the fibers. The tissue is divided in layers until the underlying joint capsule is identified.

A rongeur or curette is used to débride the dysvascular tissue and to stimulate bleeding. Avoid injury to the underlying UCL. Sometimes, a K-wire is used to puncture the medial epicondyle several times to stimulate bleeding at the origin of the tendon.

A rongeur or curette is used to débride the dysvascular tissue and to stimulate bleeding. Avoid injury to the underlying UCL. Sometimes, a K-wire is used to puncture the medial epicondyle several times to stimulate bleeding at the origin of the tendon.

The common flexor tendon is then repaired in layers using a suture. The fascia is also closed followed by the subcutaneous tissues and the skin. Most surgeons immobilize the patient in a long-arm posterior splint for 10 to 14 days.

The common flexor tendon is then repaired in layers using a suture. The fascia is also closed followed by the subcutaneous tissues and the skin. Most surgeons immobilize the patient in a long-arm posterior splint for 10 to 14 days.

Estimated postoperative course

Cubital tunnel syndrome

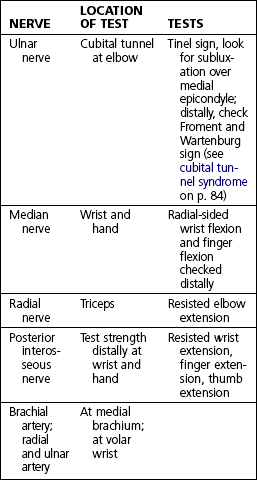

Physical examination

Tenderness over the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel

Tenderness over the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel

Positive Tinel sign over the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel, with symptoms radiating to the fourth and fifth fingers

Positive Tinel sign over the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel, with symptoms radiating to the fourth and fifth fingers

Placement of the elbow into flexion and palpation for subluxation of the ulnar nerve over the medial epicondyle

Placement of the elbow into flexion and palpation for subluxation of the ulnar nerve over the medial epicondyle

Altered or decreased sensation to touch (or two-point discrimination) of the ulnar border of the fourth finger and the entire fifth finger

Altered or decreased sensation to touch (or two-point discrimination) of the ulnar border of the fourth finger and the entire fifth finger

Inspection for intrinsic muscle atrophy in the hand, or claw deformity (late finding)

Inspection for intrinsic muscle atrophy in the hand, or claw deformity (late finding)

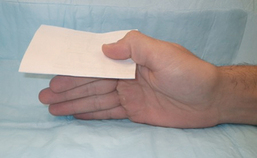

Froment sign: Figure 3-11

This test evaluates for weakness of the adductor pollicis muscle caused by ulnar nerve injury.

This test evaluates for weakness of the adductor pollicis muscle caused by ulnar nerve injury.

Ask the patient to hold a piece of paper between the thumb and index finger while the fingers are extended. The examiner then tries to remove paper from the patient’s grip.

Ask the patient to hold a piece of paper between the thumb and index finger while the fingers are extended. The examiner then tries to remove paper from the patient’s grip.

A positive sign is when the patient flexes the thumb interphalangeal joint and thereby activates the flexor pollicis longus (a median nerve innervated muscle) to hold the paper, instead of using the adductor pollicis.

A positive sign is when the patient flexes the thumb interphalangeal joint and thereby activates the flexor pollicis longus (a median nerve innervated muscle) to hold the paper, instead of using the adductor pollicis.

Initial treatment

First treatment steps

Provide the patient with education about how to avoid leaning on the elbow and flexing it for long periods of time.

Provide the patient with education about how to avoid leaning on the elbow and flexing it for long periods of time.

Discuss activity modifications.

Discuss activity modifications.

Suggest that the patient obtain an elbow pad to protect the nerve and possibly refer the patient to an occupational therapist to have a night-time splint made. Wrapping a towel around the elbow at night can also work to prevent flexion and protect the nerve from compression.

Suggest that the patient obtain an elbow pad to protect the nerve and possibly refer the patient to an occupational therapist to have a night-time splint made. Wrapping a towel around the elbow at night can also work to prevent flexion and protect the nerve from compression.

Treatment options

Conservative management is reserved for patients with no evidence of muscle wasting on EMG/NCS or physical examination and for those without any previous treatment.

Conservative management is reserved for patients with no evidence of muscle wasting on EMG/NCS or physical examination and for those without any previous treatment.

Patient education is key. Discuss in detail how the patient should avoid leaning on the elbow and flexing the elbow repetitively or for long periods of time. Discuss sleep posture.

Patient education is key. Discuss in detail how the patient should avoid leaning on the elbow and flexing the elbow repetitively or for long periods of time. Discuss sleep posture.

Operative management

Informed consent and counseling

Care will be taken to avoid injury to the cutaneous nerves at the elbow, but some residual numbness occasionally occurs near the incision site at the elbow.

Care will be taken to avoid injury to the cutaneous nerves at the elbow, but some residual numbness occasionally occurs near the incision site at the elbow.

The purpose of the surgical procedure is to relieve the sites of compression, and the goal is to prevent progression of nerve damage; if the patient has advanced disease, the operation may not restore normal sensation to the fingers, and strength may never return.

The purpose of the surgical procedure is to relieve the sites of compression, and the goal is to prevent progression of nerve damage; if the patient has advanced disease, the operation may not restore normal sensation to the fingers, and strength may never return.

The patient can expect to have limited use of the arm for about 6 to 8 weeks.

The patient can expect to have limited use of the arm for about 6 to 8 weeks.

Surgical procedures

Medial approach over the ulnar nerve at the elbow

Medial approach over the ulnar nerve at the elbow

Ulnar nerve decompression or decompression and transposition of the ulnar nerve

Ulnar nerve decompression or decompression and transposition of the ulnar nerve

Nerve transposed subcutaneously (best reserved for those with adequate subcutaneous fat) or submuscularly

Nerve transposed subcutaneously (best reserved for those with adequate subcutaneous fat) or submuscularly

Ulnar nerve transposition (subcutaneous or submuscular): Figure 3-12

Instruments: Vessel loops are used to hold the nerve gently during dissection.

Instruments: Vessel loops are used to hold the nerve gently during dissection.

A longitudinal incision is made over the medial elbow. Take care to identify and protect the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Elevate the subcutaneous flaps off the fascia overlying the flexor-pronator mass. Identify the medial epicondyle. Just posteriorly, identify the ulnar nerve within the cubital tunnel. With tenotomy scissors and smooth forceps, the ulnar nerve is carefully decompressed. Minimal traction and manipulation of the nerve are ideal, and a vessel loop can be used to retract and control the nerve gently while operating.

A longitudinal incision is made over the medial elbow. Take care to identify and protect the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Elevate the subcutaneous flaps off the fascia overlying the flexor-pronator mass. Identify the medial epicondyle. Just posteriorly, identify the ulnar nerve within the cubital tunnel. With tenotomy scissors and smooth forceps, the ulnar nerve is carefully decompressed. Minimal traction and manipulation of the nerve are ideal, and a vessel loop can be used to retract and control the nerve gently while operating.

All sites of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow are addressed: arcade of Struthers, medial intramuscular septum of the triceps, Osborne ligament, the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) fascia, and the heads of the FCU.

All sites of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow are addressed: arcade of Struthers, medial intramuscular septum of the triceps, Osborne ligament, the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) fascia, and the heads of the FCU.

If transposing subcutaneously, a sling is created within the medial subcutaneous flap. The nerve is transposed, and then a suture is used to tack the subcutaneous tissue back down to the flexor pronator fascia, thus securing the nerve anterior to the medial epicondyle.

If transposing subcutaneously, a sling is created within the medial subcutaneous flap. The nerve is transposed, and then a suture is used to tack the subcutaneous tissue back down to the flexor pronator fascia, thus securing the nerve anterior to the medial epicondyle.

If transposing submuscularly, the flexor-pronator fascia may be lengthened using a steplike incision. A trough may also be created in the musculature and the nerve transposed anterior to the medial epicondyle. The fascia is then sutured back together over the nerve but in a lengthened position.

If transposing submuscularly, the flexor-pronator fascia may be lengthened using a steplike incision. A trough may also be created in the musculature and the nerve transposed anterior to the medial epicondyle. The fascia is then sutured back together over the nerve but in a lengthened position.

Once the nerve has been transposed, the elbow is placed through ROM to ensure that the nerve no longer subluxes with flexion, has no areas of compression, and is not under tension. The wound is then irrigated and the skin closed. A Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain or similar drain may be placed into the wound to be removed before discharge home or on postoperative day 1. Most surgeons place the patient in a postoperative long-arm posterior splint with the elbow at 90 degrees and the forearm in neutral.

Once the nerve has been transposed, the elbow is placed through ROM to ensure that the nerve no longer subluxes with flexion, has no areas of compression, and is not under tension. The wound is then irrigated and the skin closed. A Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain or similar drain may be placed into the wound to be removed before discharge home or on postoperative day 1. Most surgeons place the patient in a postoperative long-arm posterior splint with the elbow at 90 degrees and the forearm in neutral.

Estimated postoperative course

Olecranon bursitis

Physical examination

Evaluation of the posterior elbow reveals an inflamed olecranon bursa.

Evaluation of the posterior elbow reveals an inflamed olecranon bursa.

Note the presence of any erythema and whether it is localized to the bursa or extends to the surrounding tissues in a cellulitic pattern.

Note the presence of any erythema and whether it is localized to the bursa or extends to the surrounding tissues in a cellulitic pattern.

Palpation of the bursa reveals bogginess and mild tenderness. Severe tenderness could indicate infection.

Palpation of the bursa reveals bogginess and mild tenderness. Severe tenderness could indicate infection.

Evaluate ROM and assess whether it is painful. Painful ROM could suggest deeper joint infection.

Evaluate ROM and assess whether it is painful. Painful ROM could suggest deeper joint infection.

Classification system: Inflammatory versus infectious

Sometimes the difference can be subtle.

Sometimes the difference can be subtle.

Infectious olecranon bursitis generally appears as beefy red, taut skin and looks very aggressive. It is generally more painful with palpation and ROM and is more likely to have associated surrounding cellulitis.

Infectious olecranon bursitis generally appears as beefy red, taut skin and looks very aggressive. It is generally more painful with palpation and ROM and is more likely to have associated surrounding cellulitis.

Inflammatory olecranon bursitis generally has localized erythema, and edema is isolated to the bursa itself. Usually, this type of bursitis is less tender to palpation.

Inflammatory olecranon bursitis generally has localized erythema, and edema is isolated to the bursa itself. Usually, this type of bursitis is less tender to palpation.

Initial treatment

Treatment options

For mild inflammatory bursitis: Suggest ice, NSAIDs, an elbow pad or elastic (Ace) wrap for compression, and avoidance of leaning on the elbow. These treatments may take several weeks to be successful.

For mild inflammatory bursitis: Suggest ice, NSAIDs, an elbow pad or elastic (Ace) wrap for compression, and avoidance of leaning on the elbow. These treatments may take several weeks to be successful.

For symptomatic inflammatory bursitis:

For symptomatic inflammatory bursitis:![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree