The elbow joint is a complex structure consisting of three separate articulations: the humerus and ulna, humerus and radius, and ulna and radius. Although it is often considered a hinge joint, the elbow allows rotation of the forearm at the radioulnar joint. Elbow stability and function are maintained by ligamentous structures.

The elbow is important to the function of the upper extremity as is used to establish contact between the hand and the body from head to toe. Even with a limited range of motion in the shoulder, most activities in daily life can be performed with a mobile elbow.

Capable of both hinged and rotary motion, the elbow is susceptible to degenerative changes and acute injuries. One need only think of the motions in sports such as tennis, gymnastics, squash, or javelin throwing. That create asymmetric stresses that could lead to damage both in the joint and in the surrounding soft-tissue cuff. Examples common are tennis elbow or golfer’s elbow. Activities such as skiing, motorcyle riding, handball, or pitching, are particularly likely to result in elbow injuries. In sports where the participant can fall on the outstretched upper extremity, the elbow often bears “the weight of the entire body. Fractures, dislocations, and ligament tears can occur.

2.2 Clinical Examination

Standard Examination

After taking a detailed history, the axis and position of the joint and the joint contours are inspected. Stand beside the patient and hold the anterior lateral upper arm when palpating the elbow. Palpate the medial epicondyle, the medial supracondylar line of the humerus, the olecranon, the posterior ulnar border, the olecranon fossa, the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, the lateral margin of the humerus, the radial head, and the various soft-tissue regions of the elbow. Motion in flexion and extension as well as pronation and supination is tested and recorded. Strength and sensation are evaluated after functional tests have been performed.

Patient History

Clinical examination of the elbow begins with taking the patient’s history. Various disorders can be caused by acute injuries, chronic stressors, degenerative changes, and systemic disorders. Finding the problem is easiest in patients with recent trauma who can precisely describe how the accident occurred. With degenerative disorders or the sequelae of chronic stressors, obtaining a precise description of events long past is of great importance. Systemic disorders that can involve the joints should not be overlooked. A knowledge of injuries to the elbow sustained in the past and of how they were treated is also important. The patient’s age has a bearing on clinical considerations. An elbow injury in a 40-year-old weekend athlete may be treated differently to one in a 25-year-old professional athlete.

Aside from age, the patient’s occupation and athletic activities are crucial aspects of the history. This information is generally helpful in evaluating chronic symptoms. Knowledge of the precise motions involved in the various activities is important; by asking specific questions the problem can be rapidly ascertained. Tennis elbow is one example of how repetitive motion can contribute to the onset of a clearly defined clinical syndrome, whether the patient is an electrician, carpenter, or tennis player.

With chronic symptoms, it is important to inquire specifically how the pain radiates, where it is localized, at what time it usually occurs (nighttime pain or motion-dependent pain), as well as about the quality of pain.

In acute trauma, a precise reconstruction of the mechanism of injury should be attempted. This is very helpful in determining whether the trauma is direct or indirect. For example, it should be determined whether the patient fell on the hand with the elbow extended or fell with his or her full body weight on the flexed joint.

Observation

Inspection and the remainder of the clinical examination should be performed with the patient undressed. Both arms should be visible from midclavicle to fingertips. This is the most reliable way to evaluate possible asymmetry or pathologic position. Often patients will exhibit pathologic patterns of motion while undressing.

Fig. 2.1 Olecranon bursitis

A valgus angle exceeding the normal range of 5° to 15° is referred to as cubitus valgus. A frequent cause of this is epiphyseal damage secondary to a fracture of the lateral epicondyle. In cubitus varus, the angle is less than 5°. This is often a result of childhood trauma, such as a supracondylar fracture where the distal humerus heals with malunion or with early physeal closure.

In addition to limitations in motion, observation should also focus on contour changes in the elbow joint. Swelling may be local or diffuse. It can be so extensive that the elbow is held at 45° flexion, the position in which the volume of the joint capsule is greatest. Frequent causes for this are crush injuries or fractures. The possibility of joint inflammation, particularly in the presence of additional erythema, should also be considered, Localized swelling above the olecranon also occurs when the olecranon bursa is swollen (Fig. 2.1).

Scars should be noted. Often they may be the cause of restricted motion or even contractures.

Palpation

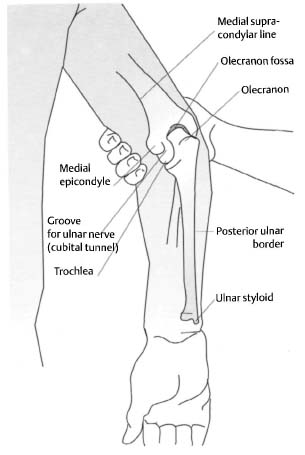

To palpate the elbow, stand beside the patient, holding the anterior lateral aspect of the upper arm. Place the elbow in approximately 90° flexion by extending and abducting the upper arm (Fig. 2.2). Crepitus that occurs during this motion may be caused by a fracture, arthritis, thickened synovia, or a bursa. Be sure to note any pain or swelling.

• Medial epicondyle

First palpate the medial epicondyle on the medial side of the humerus. It defines the contour of the medial elbow and is susceptible to fracture, particularly in children.

• Medial supracondylar line of the humerus

The medial supracondylar line can be palpated superior to the medial epicondyle. It is the structure onto which the wrist flexors insert. Occasionally a small bony prominence will be palpable in this region, which can produce compression of the median nerve.

Fig. 2.2 Palpable structures in the elbow region

• Olecranon

The olecranon is easily palpated in flexion as the proximal end of the ulna within the olecranon fossa. Neither the bursa nor the triceps tendon interfere with palpation. The skin over the olecranon is extremely loose and permits flexion of the elbow.

• Posterior ulnar border

Palpate the posterior ulnar border from the olecranon to the ulnar styloid at the wrist.

• Olecranon fossa

The olecranon fossa is located at the distal end of the posterior humerus. When the arm is extended, the olecranon disappears into a groove filled with fat and a portion of the aponeurosis of the triceps muscle. Palpation is difficult.

• Lateral epicondyle of the humerus

The lateral humeral epicondyle lies lateral to the olecranon. It is smaller than the medial epicondyle and thus more difficult to define.

• Lateral supracondylar line

This bony margin may be palpated on the lateral humerus almost as far as the deltoid tuberosity.

Placing the thumb on the medial epicondyle, the index finger on the olecranon, and the middle finger on the lateral epicondyle, you will note that the lines connecting your fingers form an isosceles triangle when the elbow is flexed 90°. When the elbow is extended, the fingers will form a straight line. Any deviation from this geometric alignment requires further examination.

• Radial head

Examine this structure with the elbow flexed 90°. The radial head will be palpable approximately 2.5 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus through the muscle mass of the wrist extensors. If the radioulnar joint can move through its full physiologic range of motion, almost three-quarters of the radial head will be palpable. The radial head is more easily palpable if dislocated.

To examine the soft tissue, the elbow should be divided into four regions.

• Medial aspect

The arm should be slightly abducted and the elbow flexed 90° for this examination.

Ulnar nerve. This is located in the groove between the medial epicondyle of the humerus and the olecranon. It can be palpated as it is gently rolled under the index and middle fingers. Thickening in this region due to scar tissue sometimes causes a tingling sensation in the patient’s ring and little fingers because of nerve compression. Injury to the ulnar nerve often occurs in supracondylar or epicondylar fractures, or as a result of direct trauma.

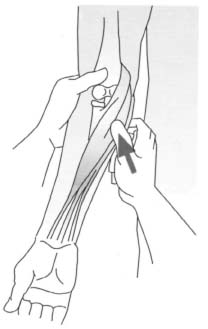

Wrist flexors and pronators. The pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, and flexor carpi ulnaris originate from the medial epicondyle as a common structure. These muscles should first be palpated as a group and then individually from radial to ulnar. Proceeding systematically from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the wrist on the flexor side, tender areas can often be located above the insertion of the muscle or along its course (Fig. 2.3). Tennis, golf, or regular use of a screwdriver can often provoke painful changes in this area.

Medial collateral ligament. This is a primary stabilizer of the humeroulnar joint. It arises from the medial epicondyle of the humerus and extends in a fan-shaped pattern to the medial margin of the trochlear notch of the ulna. This structure cannot be palpated, but pathologic changes such as valgus stress can produce tenderness.

• Posterior aspect

The olecranon defines the contour of this region.

Fig. 2.3 Palpating the wrist flexors and pronators

Olecranon bursa. This structure is only palpable in the presence of acute inflammation when it will be thickened and mobile.

Triceps muscle. Spanning two joints, the triceps with its three heads is essential for extending the elbow. The long head from its origin to the common muscle mass will be palpable along with the lateral head in the posteromedial upper arm when the muscle is slightly contracted. The lateral head of the triceps is also easily palpated in the posterolateral upper arm. All three heads of the triceps are joined in an aponeurosis proximal to the olecranon and are readily palpable as a wide thin structure. This region should be examined carefully in patients who have fallen on the elbow.

• Lateral aspect

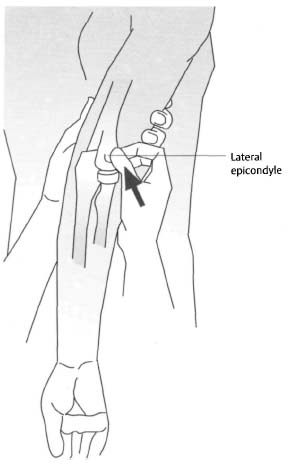

Wrist extensors. The brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, and extensor carpi radialis brevis commonly originate from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and the lateral supracondylar line. At the elbow they appear as a single unit that splits into two distinct palpable structures, the brachioradialis and the wrist extensors, on the extensor side of the forearm. The brachioradialis can be examined for tenderness and lesions up to its insertion on the ulnar styloid. As wrist extensors, these three muscles are thought to be crucial to the development of tennis elbow. Patients with this disorder will show evidence of tenderness at the common origin of these muscles (Fig. 2.4).

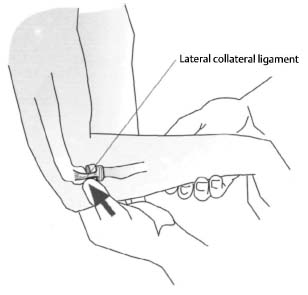

Lateral collateral ligament. This extends from the lateral epicondyle to the annular ligament. Varus stress will make it tender to palpation.

Fig. 2.4 Palpating the lateral epicondyle and the wrist extensors

Annular ligament. This ligament surrounds the capitellum and radial neck. It will only be palpable in the presence of pathologic changes in the ligaments themselves or in the radial head (Fig. 2.5).

• Anterior aspect

Cubital fossa. The cubital fossa is the triangular region bordered laterally by the brachioradialis and medially by the pronator teres. The biceps tendon, brachial artery, and the median and musculocutaneous nerves pass through this region from lateral to medial.

Biceps tendon. The biceps tendon is palpable from the muscle mass to its insertion on the radius in flexion and supination. In a distal tear the muscle and tendon retract into the upper arm, where they are visible as significant swelling.

Brachial artery. The pulse of the brachial artery is palpable in the cubital fossa medial to the biceps tendon.

Fig. 2.5 Palpating the annular ligament

Assessing Range of Motion

The range of motion in the elbow consists of four movements: flexion, extension, supination, and pronation. Flexion and extension are effected primarily by the humeroradial and humeroulnar joints, while supination and pronation are effected in the proximal and distal radioulnar joints.

Active range of motion. The patient may stand or sit for this examination. Testing the active range of motion supplies information on the patient’s ability to move the elbow without assistance.

Flexion (135°) and extension (0° or −5°). Instruct the patient to touch the shoulder with the anterior aspect of the forearm. The musculature of the upper arm usually limits flexion. Extension is limited by the olecranon, which strikes the olecranon fossa. Normal extension in men is 0°; in women up to 5° of hyperextension is normal.

Supination (90°) and pronation (90°). The supination test should be performed with the elbow in 90° flexion and the upper arm in adduction to prevent shoulder movement. From the neutral position, the patient turns the palms upward in supination and downward for pronation. The radius should rotate 180° around the ulna.

Passive range of motion. Instruct the patient to place the elbow on his or her hip while you cup the olecranon with one hand and move the forearm with the other.

Flexion and extension. Flex and extend the elbow from the neutral position as described above. Note the range of motion and the quality of the endpoint of motion.

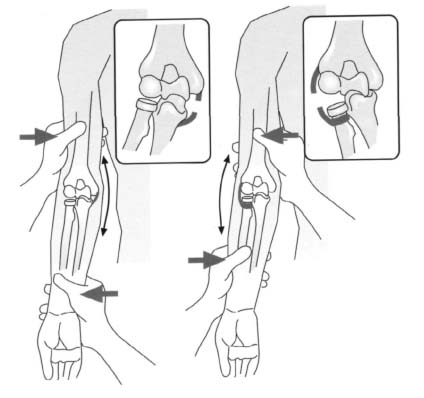

Fig. 2.6 Evaluating the collateral ligaments

Supination and pronation. Now move your hand from around the patient’s forearm to grasp the patient’s hand. Slowly move the joint into supination and pronation. Here too, note the range of motion and the quality of the endpoint of motion.

Specific Tests

Ligament instability. To evaluate the lateral and medial collateral ligaments, grasp the posterior aspect of the elbow with one hand and the wrist with the other (Fig. 2.6). While immobilizing the elbow, apply a varus or valgus stress with the hand around the patient’s wrist. With one finger of the hand mobilizing the elbow, evaluate the size of the joint cavity laterally and medially and check for tenderness.

Tinel sign. Tapping the ulnar nerve in its groove between the medial condyles and olecranon can produce a tingling sensation in the area supplied by this nerve if it is compromised.

Tennis elbow. Immobilize the patient’s elbow with one hand while palpating the origins of the wrist extensors over the lateral humeral epicondyle with the thumb. Instruct the patient to extend the wrist against resistance. In tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis) the patient will experience pain at the site of the origins of the wrist extensors.

Posterolateral instability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree