CHAPTER 3 ELBOW

A TENDON TESTS

Tennis elbow test

Clinical context

Tennis elbow is the most commonly encountered lesion at the elbow. It affects 1–3% of the population with prevalence peaking between the ages of 40 and 50 years, particularly among men, who are twice as likely to present with the condition (Bulstrode et al 2002). The common view is that it is a self-limiting condition with natural resolution within a year, but in a substantial number of cases the condition persists and can cause pain and disability for much longer (Bulstrode et al 2002), a scenario commonly encountered in clinical practice. Such a chronic presentation is usually associated with degenerative tendinopathy resulting in a reduction in tensile strength and tendon extensibility. Patients often report more diffuse pain and tenderness, functional weakness and limitation of elbow extension, particularly on waking.

There is little evidence to support the use of any particular diagnostic test for tennis elbow, although provocation of lateral elbow pain on resisted wrist extension and tenderness over the lateral epicondyle were found to be the most commonly used indicators among a sample of Scottish physiotherapists (Greenfield & Webster 2002), and, given the predictable history and well-localized pain, the clinician can be reasonably confident that positive findings to the provocative tests point strongly to a contractile lesion of the common extensor tendon.

Clinical tip

Rarely, the condition may be complicated by compression of the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve, either as a primary lesion or secondary to a tendinopathy at the CEO. Distinctively, this may result in paraesthesiae in the forearm, tenderness over the course of the nerve in the forearm, as well as the more common findings of pain on resisted third finger extension and limitation to passive elbow extension (Roles & Maudsley 1972). Care should therefore be taken in the differential diagnosis of atypical or resistant cases as radial nerve compression has the capacity to mimic tennis elbow presentation (Stanley 2006).

| EXPERT OPINION | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Tennis elbow test |

| The most common site for the condition to present is at the teno-osseous junction where the CEO (composed of ECRB, extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum and extensor indicis) attaches to the small anterior facet of the lateral epicondyle. The other potential sites to exclude are the attachment of extensor carpi radialis longus on the lower third of the lateral supracondylar ridge, the body of the common extensor tendon (approximately 2 cm distal to the CEO) and the muscle belly lying deep to the brachioradialis muscle in the forearm. |

CEO = common extensor origin

ERCB = extensor carpi radialis brevis

Related tests

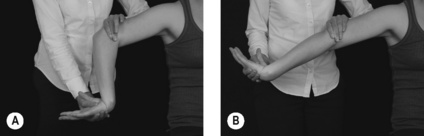

While the majority of tests aim to test the contractile unit by generating a contraction, the Mills’ test (Fig. 3.2) involves the application of a passive longitudinal stretch to the tendon. The patient sits with the shoulder slightly abducted, elbow flexed to 90°, forearm pronated and wrist flexed so that the palm of the hand is facing the ceiling. Standing behind the patient on the affected side, one hand cups the upper arm for support and takes the arm into about 70° of abduction. The thumb of the other hand is then placed in the patient’s palm between the index finger and thumb and the fingers wrapped around the dorsum of the wrist, which enables the forearm to be maintained in full pronation and the wrist in flexion. While maintaining this position, the elbow is extended slowly (see Fig. 3.2A and Fig. 3.2B). A positive test is indicated by reproduction of the patient’s pain over the common extensors and, depending on the chronicity and severity, will occur in varying degrees of terminal extension. This test can also place considerable stress on the radial nerve and careful discrimination should therefore be exercised to exclude neural involvement. Stress on the nerve can be minimized by any or all of the following: reducing the degree of shoulder abduction, avoiding taking the shoulder into extension, allowing some elevation of the shoulder girdle, and placing the cervical spine in a degree of side-flexion towards the painful elbow.

Golfer’s elbow test

Technique

Clinician position

Standing adjacent to the patient’s affected side using the hand nearest the patient, the clinician fixes the lower forearm while supporting the patient’s upper arm over the crook of the elbow. The other hand is formed into a fist and placed in the palm of the patient’s flexed wrist.

Clinical context

The term medial epicondylitis implies that the process is purely inflammatory but golfer’s elbow is more accurately described as a degenerative tendinopathy involving the common flexor tendons at their attachment on the anterior aspect of the medial epicondyle of the humerus. The underlying pathology is similar in both tennis and golfer’s elbow where collagen formation becomes disordered with increased fibroblast and vascular content apparent (Atkins et al 2010). In tennis elbow, this process has been associated with tendon tears, although such significant breakdown of the tendon is uncommon at the CFO (Bulstrode et al 2002). The muscles most commonly contributing to unaccustomed or overuse loading of the CFO are pronator teres and flexor carpi radialis, with the others (palmaris longus, flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum superficialis) less commonly involved (Bulstrode et al 2002). Because of the close proximity of the ulnar nerve to the CFO, ulnar nerve symptoms may co-exist in some patients with golfer’s elbow (Bulstrode et al 2002) and the presence of paraesthesiae distal to the site of compression would require further evaluation (see Tinel’s test, p. 103, and the ulnar nerve flexion test, p. 107).

There is no evidence on the accuracy of this test although, given the very specific presentation of this condition, the clinician can be reasonably confident that a positive test is diagnostic.

B LIGAMENT/INSTABILITY TESTS

Valgus test

Technique

Clinical context

Valgus instability can occur following an acute injury or as a result of chronic strain. Rupture of the MCL following trauma may be associated with injury to other medial structures such as the common flexor origin (CFO) and ulnar nerve. Repeated high-speed overhead activities associated with throwing sports can also result in microtrauma and chronic strain. If other medial structures are affected, the patient may complain of pain, weakness, neurological symptoms or flexion contracture secondary to posteromedial olecranon impingement (Lee & Rosenwasser 1999).

A study examining the range of valgus movement in cadavers where the MCL was compromised by a surgical incision found that complete release was required for between 4 and 10 mm of ulnohumeral joint gapping to be noted arthroscopically. The maximum opening was seen with the radio-ulnar joint positioned in pronation with between 60° and 75° of elbow flexion (Field & Altchek 1996), which suggests that in order to stress the ligament comprehensively the test should be repeated in this position (see variations). In a study of normal elbows, significant gapping was noted under radiographic examination when 25N of valgus stress was applied; this degree of ‘normal’ gapping may lead the clinician to falsely identify instability unless comparison with the opposite limb is made (Lee et al 1998).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree