Abstract

Objective

Physical therapy strategies have recently proved their efficacy in the field of Parkinson’s disease management. The purpose of this paper was to access the efficacy and the limits of aerobic training and strength training included in physical rehabilitation programs and to define practical modalities.

Method

A comprehensive search on Pubmed and Cochrane databases was made.

Results

Five literature revues and thirty one randomised trials have been selected. Exercise training improves aerobic capacities, muscle strength, walking, posture and balance parameters. Rehabilitation programs should begin as soon as possible, last several weeks and be repeated. They should include aerobic training on bicycle or treadmill and a muscle strengthening program.

Conclusion

There is evidence that aerobic and strength training improve physical habilities of patients suffering from Parkinson’s Disease. Rehabilitation programs should be discussed with the patient, taking in account his difficulties and his physical capacities. Two questions are debatable: exercise intensity and phase ON / phase OFF timing.

Résumé

Objectifs

La maladie de Parkinson idiopathique est progressivement invalidante et incomplètement contrôlée par les thérapeutiques médicamenteuses. La prise en charge non médicamenteuse conjointe s’est parallèlement étoffée avec de nouvelles approches intéressantes parmi lesquelles le réentraînement à l’effort. L’objectif de ce travail est, à partir des données de la littérature, de préciser les preuves scientifiques de l’intérêt et des limites du réentraînement à l’effort et d’en déterminer les modalités pratiques.

Matériel et méthode

Une revue de la littérature a été faite à partir des moteurs de recherche Pubmed et Cochrane.

Résultats

Cinq revues de la littérature et 31 essais randomisés ont été inclus. Le réentraînement à l’effort améliore les capacités aérobies d’adaptation à l’effort, la force musculaire, le schéma de marche, la posture, l’équilibre et la qualité de vie de ces patients. Il doit être débuté le plus tôt possible, prolongé, répété dans le temps et doit associer un travail sur cycloergomètre ou tapis de marche à un renforcement musculaire global.

Conclusion

Le réentraînement à l’effort apporte des bénéfices certains chez les patients parkinsoniens, le protocole doit être individualisé en fonction des doléances et des capacités du patient. Deux questions sont encore débattues : l’intensité d’exercice et l’horaire à privilégier.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a degenerative disorder of the central nervous system with an unknown etiology. It should be differentiated from Parkinson syndromes, which can be induced by infections, drugs, environmental toxins as well as vascular disorders or tumors and Parkinson-plus syndromes (group of neurodegenerative diseases including multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration and Dementia with Lewy bodies). PD is the most common neurodegenerative affection second only to Alzheimer’s disease. In spite of advances in drug therapeutics, PD often leads to impairments and severe disabilities. PD is the second leading cause of neurological impairments (ischemic stroke being the first one).

With the aging of the population and subsequent increase in PD patients, care management of this disorder is becoming a public health challenge.

Rehabilitation care of patients with PD has improved in the past years, especially for motor and language impairments. Rehabilitation techniques must be adapted to the disease’s stage. Based on experiences in animal models, strength training has become a large part of rehabilitation care programs for patients with PD. Several recent randomized, controlled studies have highlighted its benefits. However, because of the heterogeneity in exercise parameters and patients’ demographics, it is difficult for PM&R teams to implement it in daily practice.

The objectives of this study, in light of literature data were first to determine the relevance of strength training in PD and second to refine practical modalities for clinical applications.

1.2

Parkinson’s disease: evaluation scales

Several tools for the clinical evaluation of patients with PD have been validated and are used in clinical settings:

- •

global evaluation scales, such as the Hoehn and Yahr scale , reliable but not very sensitive to change, it allows the classification of patients into 5 stages according to the disease’ progression;

- •

analytical evaluation scales, to appreciate the intensity of each clinical symptom (Webster Scale for example);

- •

functional scales measuring the impact of PD on daily life activities (PDQ-39 );

- •

multidimensional scales to better assess the real situation of patients; the most commonly used scale is the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) . Its section III (motor examination), at the first stages of the disease, can help monitor its progression and adapt the treatment. It is also a helpful diagnostic tool since a score improvement > 50%, 3 to 5 years after having implemented Dopamine replacement therapy, points towards a diagnosis of idiopathic PD ;

- •

generic scales exploring more specifically cognitive and psychological functions as well as motor fluctuations.

The progression of PD consists in three stages: the “honeymoon” stage (1 to 8 years) during which drugs are quite effective in managing the disorders; the second stage, in average 4 to 5 years after the onset of the disease, when motor complications related to Dopamine replacement therapy (DRT) start to appear (end-of-dose akinesia, ON-OFF phenomena, dyskinesia at the middle of the dose, biphasic dyskinesia); the third stage, labeled “advanced” or “decline” stage, during which DRT is no longer effective and axial motor symptoms (posture and balance disorders, falls, dysarthria/dysphagia), cognitive/behavioral disorders and autonomic dysfunction (Dysautonomia) become predominant.

1.3

Conventional rehabilitation techniques used in patients with Parkinson’s disease

Several PM&R techniques have proven their efficacy and are used in clinical settings for the care management of patients with PD. The choice of these techniques must be guided by the disease stage.

1.3.1

Stretching and muscle resistance training

Muscle resistance training for quadriceps, hamstrings and foot extensors improves bradykinesia, muscle stiffness as well as gait and balance parameters . In idiopathic PD, there is an imbalance between agonist muscles that facilitate opening movements (e.g. extensors, supinator muscles, external rotators, scapula and pelvic abductors) and antagonist muscles that facilitate closing movements (flexors, pronators, internal rotators and adductors), as evidenced by the difficulties encountered for quick, alternative movement in pronation-supination or flexion-extension . Physical therapy programs must include passive stretching of antagonist muscles and strengthening of agonist muscles . Some exercises for active mobilization in axial rotation should be implemented to fight stiffness, which affects the trunk. Tai Chi exercises can also help reduce balance disorders .

1.3.2

Attentional strategies

1.3.2.1

Cognitive strategies

It has been validated that focalizing the attention of PD patients on a task actually improves its performance . Verbal instructions or “cognitive cueing” were the first strategies studied: for example, asking patients to focus on performing ample steps , or swinging their arms exaggeratedly when walking to fight bradykinesia. It is important to recommend to patients to plan and mentally visualize the movement beforehand, concentrate on the movements while performing it and break down a complex task into simple sub sequences. Dual-task conditions deteriorate motor performances in PD patients , and it is recommended to learn to eliminate dual-task situations at an advanced stage of the disease. However, Brauer and Morris as well as Canning et al. reported that dual-task training in mild and moderate stages of PD associated with verbal instructions to help patients focus on their gait, reversed motor deterioration and improved gait parameters .

1.3.2.2

Cueing or sensory cues

Using external sensory signals (visual or auditory ones) improves performance while increasing the patient’s focus on the motor task (gait, half turns) and decreases freezing . It promotes movements usually controlled by the frontal cortex, and decreases the relay, which usually takes place at the level of the basal nuclei for automatic movements, which are impaired in patients with PD . For example, using a metronome or “clapping hands” to rhythm the steps or, taping horizontal lines on the floor that the patient must cross at each step passage.

1.3.3

Motor strategies

Motor strategies are designed to keep the gestures simple and easy, such as movements with wide range of motion , as well as performing varied and repeated exercises dedicated to a precise daily activity to optimize training and facilitate the transfer of rehabilitation improvements into the patient’s daily life (working on gait patterns while varying the distances, type of floor and speed) . Motor learning consists in three stages associating cognitive and motor strategies: task planning, focusing on movements while performing them and implementing automated tasks with the motor strategies described above, with or without dual-task training .

1.3.4

Behavioral strategies

They are helpful in specific situations that usually trigger difficulties for patients with PD. For example, to fight kinetic freezing the therapist can suggest swinging the body’s weight from one side to the other, or saying out loud “go” .

1.3.5

Other techniques

Other techniques, not specific to patients with PD, are regularly used, such as balance and postural training (learning to implement corrective strategies to fight imbalance), global coordination exercises as well as transfers and getting off the floor exercises.

A Cochrane review conducted in 2001, grouped 7 randomized, controlled studies. Its objective was to compare the efficacy of the various rehabilitation techniques: visual or auditory cueing, muscle resistance exercises associated or not with balance training, neuromotor facilitation techniques, Bobath, relaxation, karate and stretching: yet, the level of evidence was insufficient to determine the superiority of one of these techniques .

Another review of the literature, including 33 randomized, controlled studies and published in 2012 studied the efficacy of physical rehabilitation therapies vs. no therapy at all: short term improvements (< 3 months) were observed for gait speed, getting up from a chair, balance according to the Berg scale and incapacity according to the EEUMP scale .

1.4

Impact of Parkinson’s disease and its treatments on cardio-pulmonary and muscular systems

Most patients with idiopathic PD are older and the physiological effects of aging combined with those of PD have a negative impact on their physical capacity and endurance.

With age, VO 2 max (indicator of the aerobic metabolism capacity to produce energy at peak exercise level) decreases . This decrease has multiple origins associating peripheral (muscular and vascular) and central (cardiac and respiratory) factors. Furthermore, the degenerative loss of skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) sets in progressively . It concerns mostly fast twitch (Type II) muscle fibers with a decrease in size and numbers. Also, the quality of the muscle is deteriorating which induces a loss of muscle strength. The second peripheral factor is the vascular system with higher systolic blood pressure at rest and during exercise (by decreased compliance); diastolic blood pressure remains stable . On a cardiac level, there is also a decreased left ventricular compliance, and a decreased adrenergic sensitivity. The combination of these elements induces a reduction in the maximum heart rate (HRmax) during efforts as well as a decreased end-systolic volume resulting in a weaker cardiac blood flow. Regarding the pulmonary system, there is a loss of thoracic flexibility leading to a reduction in vital capacity, in FEV1 and an increase in residual volume .

If physiological aging induces a reduction in aerobic capacity, it was reported that subjects with PD have a lower maximum exercise capacity compared to healthy subjects matched for age, especially in moderate and severe stages of the disease . In subjects with mild PD, VO 2 max was reported to be similar to that of healthy controls . These limitations, validated by exercise tests, have been correlated to a reduction in the level of physical activity compared to healthy controls matched for age . This decrease in exercise capacity is not only the consequence of disease-related motor impairments. Lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway directly alter the different central and peripheral components.

Concerning the cardiovascular system, lesions of the autonomic nervous system, documented by the presence of Lewy bodies found in lymph nodes and axons of the sympathetic chains and within the orthosympathetic and parasympathetic centers , trigger orthostatic hypotension in about 20% of patients often associated with postprandial hypotension . A reversed high blood pressure circadian rhythm can sometimes be observed in patients with PD who experience hypertension while lying down at night . These disorders are related to the adverse side effects of some treatments used in PD (especially dopaminergic agonists, L-Dopa and monoamine oxidase B inhibitors), but also to the pathology itself . Specific cardiac abnormalities seem quite rare: no ECG abnormalities or heart rhythm disorders have been described. Very few studies have focused on differences in cardiovascular adaptations in subjects with PD vs. healthy controls matched for age during exercise. Reuter et al. found a lower systolic blood pressure during exercise in subjects with PD, but results were not significant . Palma et al. observed a lower HRmax in patients with PD vs. controls, at the same exercise intensity .

On a pulmonary level, there is an abnormal prevalence of restrictive patterns of pulmonary dysfunction in patients with PD , with lower inspiratory pressures (IP) and expiratory pressures (EP), and this right from the early stages of the disease . Several mechanisms have been described to explain these dysfunctions: deformation of the thoracic chest and spine in anteflexion , rigidity and bradykinesia of respiratory muscles as well as a direct consequence of the altered nigrostriatal pathway .

Regarding the muscular system, subjects with PD do not show specific lesions of muscle fibers; however motor capacities are diminished compared to healthy controls matched for age , due in part to bradykinesia and rigidity , which interfere with movements .

Thus, care management of subjects with PD must be comprehensive and take into account the cardiorespiratory consequences of this pathology in order for patients to maintain optimum physical abilities.

1.5

Strength training and Parkinson’s disease: from animal model to human applications

Besides the validated physiological effects of strength training on the muscle itself (optimization of the mitochondrial capacity to produce ATP, increase mitochondria size and numbers, optimized use of energetic substrate, adaptation of the muscle type) and on the cardiorespiratory system (increased heart mass, total blood volume, systolic ejection volume and maximum heart flow, improvement in the peripheral oxygen extraction, better blood pressure control, optimized blood flow and ventilator control), the animal model allowed to study the effects of strength training on the brain, especially in the framework of Parkinson’s disease.

The first studies showed that exercise activity in rats increased the rate of dopaminergic metabolites in the striatum, thus bringing up the use of dopamine during physical exercise . Other studies have validated the increased synthesis and freeing of dopamine following physical activity in rats . Furthermore, it has been reported in animal models that exercise induced neuroplasticity, neuroprotection and increased tissue trophicity .

The same observations were reported for healthy subjects with increased endogenous dopamine production after physical exercise . However, there is still no confirmation that exercise in subjects with PD induces additional freeing of dopamine and contributes to slowing down the progressive loss of dopaminergic cells . Finally, several studies have validated an improved efficacy of L-Dopa and its absorption during long-lasting physical effort, by the increased blood flow to the brain induced by exercise .

1.6

Benefits and limits of strength training in persons with Parkinson’s disease: review of the literature

1.6.1

Methodology

A review of the literature was conducted in the Pubmed and Cochrane databases, using the following keywords: Parkinson’s disease, exercise therapy, aerobic training, strength training and treadmill training. Four reviews, 1 meta-analysis and 31 randomized studies were included.

1.6.2

Results

1.6.2.1

Positive effects of strength training in patients with PD

1.6.2.1.1

VO 2 max

VO 2 max measures taken before and after the strength training protocol were used as evaluation criteria in 4 studies ( Table 1 ). VO 2 max value was determined by a stress test on a cycle ergometer with time increments (+25 watts/3 min) in Ridgel study , with slope ramp increments for Bergen et al. and on a treadmill for Shulman et al. (started at a comfortable speed and 0% slope, followed by slope ramp increments [+2% slope per minute]). In the study by Schenkman et al. , the VO 2 max value was determined at the end of a 5-minute walk with 4 different speeds. VO 2 max was significantly improved at the end of the strength training program in all studies, with a long lasting effect at 16 months in the study by Schenkman.

| Study | Training intensity | Frequency | Duration | VO 2 max evolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergen et al. (2002) | 2 groups 5 minutes stretching followed by exercises on a cycle ergometer for 10 minutes at 60–70% of HRReserve (HRR), then 10 minutes on a treadmill at 60–70% of HRR. Five minutes increase on each apparatus every 4 weeks 1 control group | 3/week | 16 weeks | VO 2 peak: +25% in group 1: Pmax +32% VO 2 peaks: −12.5% in group 2 ; Pmax: −10% |

| Ridgel et al. (2009) | 2 groups No resistance: biking on a cycle ergometer at comfortable speed (comfortable HR) for 40 minutes, 10 minutes warming up and 10 minutes recovery With resistance: biking at +30% of comfortable HR | 3/week | 8 weeks | +11% in group 1 and 17% in group 2 (no significant difference between both groups) |

| Schenkman et al. (2012) | 3 groups Group 1: stretching/functional exercises gait-balance Group 2: aerobic exercise on a cycle ergometer or elliptic bike: 5 minutes of warming up then 30 minutes at 70–80% of HR max followed by 5 minutes of recovery Group 3: at home: stretching and muscle resistance, supervised by a physiotherapist | 3/week for 4 months then 1/month; + at home: 2 to 4/week Group 3: 5 to 7/week | 16 months | Increase in VO 2 max greater in group 2 (+13%), lingering effect at 16 months |

| Shulman et al. (2013) | 3 groups High intensity: starting at HR rest +50% of HRR for 15 min. Increase every 2 weeks by 5 min, +0.2 km/h, +1% slope, up to 30 minutes of exercise at 70–80% of HRR Low intensity: starting at comfortable speed, 0% slope, 15 min. Five minutes increments every two weeks, up to 50 min at 40–50% HRR Stretching and muscle resistance training: 2 series of 10 repetitions, resistance increase according to tolerance | 3/week | 3 months | +8% in groups 1 and 2 ( P < 0.005). No effect in group 3 |

1.6.2.1.2

Muscle strength

Goodwin et al. , in a meta-analysis of 14 articles, concluded to an improvement of muscle strength of the lower limbs after strength training. The 2010 Cochrane review , on 8 studies mainly on treadmill strength training, also reported an improvement of muscle strength parameters.

1.6.2.1.3

Gait parameters and balance

These clinical parameters were reported by 5 reviews of the literature, the last one from 2010 ( Table 2 ). Two of these reviews focused exclusively on treadmill strength training , other reviews included studies on comprehensive strength training (muscle strength training, cycle ergometer, treadmill, with/without unloading exercises), randomized controlled or not, vs. physical therapy or control group. Authors reported:

- •

improvement in gait speed and step length, even more so when the training program was combined with cueing strategies ;

- •

improvement in transfer capacities (improvement of the Timed Up and Go Test TUGT);

- •

improvement in balance: the 2 scales most used in the studies were the Berg Balance Scale and the Functional Reach Test;

- •

Quality of life improvement.

| Review | Number of patients | Inclusion criteria | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crizzle et al. (2006) (abstract) | 438 | 7 studies focused on strength training or physical therapies in patients with PD, the results include data and effects of strength training | Improvement of physical performances (not detailed in the abstract) |

| Kaus et al. (2007) | Not indicated | 29 studies focused on strength training or physical therapies in patients with PD | Improvement of balance and muscle strength after strength training, improvement of gait parameters thanks to cues strategies |

| Goodwin et al. (2008) | 495 | 14 randomized controlled studies on the effect of strength training on functional abilities/number of falls/quality of life | Improvement of the following parameters: muscle strength, balance, posture, gait speed (SMD = 0.47, CI95% [0.12–0.82]). Insufficient evidence for the reduction in falls and depression |

| Herman et al. (2009) | 260 | 14 studies focusing on the effect of strength training on a treadmill on gait parameters in patients with PD | Improvements in gait speed (+13%, P = 0.014) and step length (+7%, P = 0.012) on the short term (3 studies) and on the long term (1.16 ± 0.24 m/s P = 0.028 and 1.26 ± 0.21 m, P = 0.043) (11 studies), as well as balance improvements (+12%, P 0.008) |

| Mehrholz et al. (2010) | 203 | 8 randomized controlled studies on benefits of treadmill strength training on gait parameters | Improvements in gait speed (SMD = 0.5, CI95% = [0.17–0.83]) and step length (SMD = 0.42, CI95% [0–0.84]) |

Most recently, 5 studies obtained similar results (no significant results in Carda’s study ) ( Table 3 ) with an increase in gait speed and step length and improved balance.

| Study | Population recruited | Training protocol | Inclusion criteria | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carda et al. (2012) | 15 patients with PD stages I and II H&Y scale Phase ON | Strength training on Lokomat under unloading conditions vs. treadmill training. 3 sessions per week/4 weeks | TD6M T10m TUGT UPDRS | Significant improvement of gait perimeter in both groups (+13% and +16%) no difference between the groups ( P = 0.53) No significant different between the groups (+10% and +13%) No significant different between the groups (+14% and +20%) No significant different between the groups (+4% and +7%) |

| Picelli et al. (2012) | 34 patients with PD stages III and IV H&Y scale | Strength training on a cycle ergometer with assisted cycling (Robotic Training), patient held by a harness. Progressive increments. Control group: joint mobilization, stretching. 3 × 40 minutes/week for 4 weeks | Berg TUGT T10m UPDRS | Improvement of balance (+15%) TUGT (+11%) Gait speed (+11%) UPDRS score (+13%) |

| Schenkman et al. (2012) | 121 patients with PD stages I to III H&Y | 3 groups: stretching/functional exercises and gait, aerobic training on a cycle ergo meter; group control training at home 3 days/week for 4 months then 1/month for 12 months | Continuous Scale Physical Functional Performance Functional reach test VO 2 max UPDRS PDQ-39 | Improvement of all scores in the 3 groups |

| Rose et al. (2013) | 13 patients with PD stages III to V H&Y | Strength training on a treadmill under unloading conditions, progressive increments 3 × 1 h/week for 8 weeks | UPDRS PDQ-39 TD6M | Significant increase: UPDRS score (+19.5%) Quality of life (32.6%) Gait perimeter (10.6%) |

| Shulman et al. (2013) | 67 patients with PD stages I to III H&Y | Strength training on a treadmill (1 low intensity group, 1 high intensity group). 1 stretching and muscle resistance training. 3 sessions per week/3 months | T10m VO 2 max 1RM quadriceps/hamstrings UPDRS Beck Depression Inventory, Parkinson fatigue Scale, Falls efficacy Scale | Increase gait speed (+11%, +6%, +9%) VO 2 max (+8% groups 1 and 2), 1RM (quadriceps: +1%, 3%, 15.7%; hamstrings: +4%, 8%, 16%) UPDRS (group 3 only: −3.5 points) No improvements on quality of life, fatigue, depression, fear of falling |

1.6.2.1.4

Number of falls

One study , included in the Goodwin review, evaluated the number of falls on 8 subjects with PD, before and after treadmill training at a given speed, higher than the subjects’ comfortable speed (patients were supported by a harness) for 3 hours per week during 8 weeks. They found a significant decrease in the number of falls. In the study by Shulman et al. , authors integrated the Falls Efficacy Scale as an outcome parameter; this scale evaluates the patient’s fear of falling. The results were not significant, however the study included patients in mild and moderate stages of the disease, thus with a lesser risk of falls and subsequently less afraid of falling .

1.6.2.1.5

Depression

Several studies have analyzed the impact of strength training on depression, which has a high prevalence in subjects with PD. It varies according to the patient’s age and disease’s stage, between 15.6% at stages I–II on the Hoehn and Yahr scale and 48% at stages IV–V . In most cases these results were not significant .

1.6.2.1.6

Cognitive functions

In subjects with PD, the prevalence of cognitive disorders also varies according to age and disease’s stage (ranging from 12 to 59%) . Tanaka et al. , evaluated the impact of strength training on cognitive functions according to the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in 20 patients with PD (stages I to III), after aerobic training with a progressive increase of exercise intensity, associating muscle strengthening, stretching and motor coordination exercises for 3 hours per week during 6 months. The authors reported a significant improvement of executive functions. Another study found similar results .

1.6.2.1.7

Effect on a multidimensional evaluation with the UPDRS score

A meta-analysis in the review by Goodwin et al. collected the data of 9 studies and concluded to a significant improvement of the UPDRS III score. Most recent studies obtained similar results . For Shulman et al. , the increase in UPDRS score was higher in the group, which had strength training and stretching vs. the group which had treadmill training (low and high intensity).

1.6.2.1.8

Effect on L-Dopa drug therapy

Reuter et al. showed an improved absorption and efficacy of exogenous levodopa, with increased plasma L-dopa concentrations after 2 hours of continuous aerobic exercise (50 watts on an ergocycle). Carter et al. , reported similar results even though the results were not significant. Two other studies found no effect . Thus, it is difficult to come to a conclusion, nevertheless none of these studies focused on power training (80% of maximum capacities).

1.6.2.1.9

Influence on the evolution of the disease

No study can help validate the efficacy of physical activity on the disease’ progression, nevertheless a retrospective study found a lower incidence of PD in patients who exercised regularly . Furthermore, in the study by Fisher et al. , a recording of the corticomotor excitability by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) was performed before and after an endurance and power strength training program: improved corticomotor excitability was found after a high intensity strength training program which could suggest a neuroplasticity phenomenon. Finally, Kuroda et al. found a positive relationship between exercising and longevity in subjects with PD .

Overall, these studies and meta-analyses can validate the relevance of strength training in patients with PD: it can improve functional autonomy with an increase in aerobic adaptation capacities during efforts, increased muscle strength, gait speed and step length but also improved posture and balance, all of these having a positive impact on quality of life for these persons. The effects of strength training are less obvious on decreasing the number of falls, improving cognitive abilities, depression and potential influence on the evolution of the disease, they would need to be further investigated in future studies.

1.6.2.2

Muscle resistance training in patients with PD

Haas et al. studied the impact of a muscle resistance training program for the lower limbs on gait parameters (biomechanical analysis): 18 patients with PD followed a muscle resistance training program at 70% of the one rep max (1RM). The 11-week program consisted in 18 sessions of 2 series each consisting in 12 to 20 repetitions.

Gait parameters were significantly improved with increased gait speed (+11%), increased step length (+22%) and increased step initiation speed (+29%).

Hirsch et al. compared the effectiveness of a 10-week high intensity muscle resistance training program for the lower limbs associated with balance training on a posturography platform vs. balance training alone. Improvements of balance parameters were greater in the combined group ( P = 0.006) and lingered for 4 weeks after the end of the training program.

One study compared concentric vs. eccentric muscle resistance training programs: the increased quadriceps strength was higher in the second group .

1.6.2.3

Compliance and tolerance

These elements were evaluated in a review of the literature done in 2001 , which included 53 randomized controlled studies on strength training or physical therapies in patients with PD. Patient compliance was good in all studies (85% in average). Only 15 studies reported adverse events (28%). They were rare. In fact in one study focusing specifically on strength training, the adverse events were cardiovascular ones (extrasystoles) in 2 patients during treadmill training. The program consisted in: starting at the patient’s “comfort” speed for 5 minutes, followed by an increase of 0.6 km/h every 5 minutes according to the patient’s tolerance, for a maximum training time of 30 minutes 3 times per week during 8 weeks . The other reported adverse event was muscle pain during a 12-week strength training program at 60% of 1RM .

Patient compliance and tolerance for strength training program seemed quite good, nevertheless results must be interpreted with caution because of selection bias, since patients recruited in these studies were generally the most motivated, cardiovascular risk factors were an exclusion criterion and very few studies reported adverse events.

1.6.2.4

Structure of strength training programs

1.6.2.4.1

Target population

Most studies included patients with PD at a mild or moderate stage of the disease: mean of Stage II for the Cochrane review, aged 61 to 74 years , as well as in the review by Goodwin et al. (mean age of 71 years) . Picelli et al. included 34 patients at a moderate stage of PD (III–IV according to Hoehn and Yahr classification), who performed exercises on a motorized cycle ergometer (no resistance and low speed), for safety the patient was maintained by harness because of posture and balance dysfunctions at this stage of the disease: no adverse event was reported, results showed a significant improvement in balance, gait speed and motor UPDRS . One single case reported by Schlick evaluated the benefits of a strength training program in a 65-year-old female patient at stage V of the disease: the program consisted in 6 sessions of treadmill strength training in unloading condition with a harness. The patient had to walk without and with visual cues (marks on the treadmill). Gait parameters were improved (recovered gait ability on a few meters with a walker), even more significantly so with the visual cues .

1.6.2.4.2

Type of exercise

No study has compared the effectiveness of strength training on two different types of ergometers, thus no recommendations can be made regarding the type of equipment for strength training in patients with PD. Nevertheless, the choice is obviously driven by the patient’s motor capacities, to allow for a minimum exercise intensity and maximum safety for the patient. Seven studies compared strength training exercises vs. different rehabilitation exercises ( Table 4 ):

- •

strength training program vs. Stretching and muscle resistance training ± gait pattern training (5 studies): strength training yielded more improvements on gait speed, VO 2 max and balance. No significant difference was found for UPDRS score and quality of life improvements ;

- •

the training program for the control group focused essentially on gait functional exercises, and the strength training group showed higher improvements for gait speed and step length for both endurance and power training .

| Study | Population recruited | Training protocol | Inclusion criteria | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miyai et al. (2000) | 10 patients with PD stages II–III H&Y | 2 groups in crossover, 3 × 45 min/week during 4 weeks/group Strength training group: treadmill with unloading at 20% for 15 min then 10%/15 min then 0%/15 min; speed increments of 0.5 km/h up to 3km/h Control group: exercises in daily life activities, gait, transfers | UPDRS T10m TD6M | Decrease in UDPRS score in group 1 (−6 pts) but not in group 2 (−1 pt) ( P < 0.0001); no difference according to the order Increase gait speed > group 1 (−10 s/10 m and 0.6 s/10 m, P = 0.004), no difference according to the order Increase gait perimeter > group 1 (+27 m and +20 m, P = 0.2) |

| Miyai et al. (2002) | 24 patients with PD stages II–III H&Y | Same protocol | UPDRS, T10m and TD6M | Same results as in 2000; the only difference between groups lingering at 4 months post-intervention: increased step length (−3 steps/10 m and +1 step/10 m, P = 0.006) |

| Pohl et al. (2003) | 17 patients with PD stages I–III H&Y | 4 groups. One 30-min session in each group over 4 consecutive days Treadmill with speed increments: starting at comfortable speed, then +10%/10 s Treadmill with no increments: comfortable speed Physical therapy group: functional gait exercises Control group: sitting on a chair | T10m | Significant improvement in speed and step length in the first 2 groups (+0.2 m/s and +0.17 m/s, +0.07 m, +0.06 m) ( P < 0.001). No significant improvement in the 3rd group (+0.04 m/s, +0.01 m), no increase in the control group. No significant difference between the 1st and 2nd group |

| Fisher et al. (2008) | 13 patients with PD stages I–II H&Y | 3 groups, 24 sessions over 8 weeks High intensity group: treadmill with 10% body unloading, effort intensity > 3 METs or 75% of the theoretical HRmax Progressive increments according to tolerance Low intensity group: physical therapy associating gait, balance and stretching exercises: < 3 METS Control group: therapeutic education | UPDRS T10m Gait biomechanics analysis Transcranial magnetic stimulation | Improvement of the UPDRS in the first two groups (−3 points and −5 points) without any significant difference between the groups Group 1 showed a greater increase in length (+0.04 m and +0.01 m), height (+0.02 m and 0.01 m), as well as gait speed (+0.1 m/s, +0.02 m/s) (no P ) Better corticomotor excitability in group 1 |

| Picelli et al. (2012) | 34 patients with PD stages III–IV H&Y | 2 groups: 3 × 40 minutes/week for 4 weeks Strength training on cycle ergometer with motorized cycle (robotic training) patient maintained upright with a harness. Progressive increments Control group: joint mobilization, stretching | Berg TUGT T10m motor UPDRS | Balance improvement (+15% and +4.6%) TUGT (+11% and 3.6%), gait speed (+11%, +8%) UPDRS motor score (+13% and 1.3%), significant improvement in group 1 ( P < 0.01) |

| Schenkman et al. (2012) | 121 patients with PD stages I–III H&Y | 3 groups: for 16 months, 3 days/week for 4 months then 1/month for 12 months Group 1: stretching/functional gait + balance Group 2: aerobic exercises on a cycle ergometer or on an elliptic bike: 5 min stretching then 30 min at 70–80% of the HRmax followed by 5 min recovery Group 3: at home: stretching and muscle resistance training, supervised by a physiotherapist | Continuous Scale Physical Functional Performance Functional Reach test VO 2 max UPDRS PDQ-39 | Improvement of the functional scores group 1 > group 3 (5MD = 4.3, CI95% [1.2–7]) and group 2 (SMD = 3.1, CI95% [0–3.2]) Improvement in VO 2 max group 2 > group 1 (SMD = 4.3, CI95% [−1.9, −0.5]), only significantly improved parameter at 16 months Improvement in UPDRS score and quality of life in the 3 groups without any significant difference between the 3 groups |

| Shulman et al. (2013) | 67 patients with PD stages I–III H&Y | 3 groups: 3/weeks for 3 months High intensity (23 patients): starting at 50% of HRR for 15 min, 5 min increase every 2 weeks, +0.2 km/h, +1% slope, up to 30 min of exercises at 70–80% of HRR Low intensity (22 patients): starting at a comfortable speed, 0% slope, 15 min 5-min increments every two weeks, up to 50 min at 40–50% of HRR Stretching and muscle resistance training (22 patients): 2 series of 10 repetitions, increased resistance according to tolerance | T10m VO 2 max 1 RM quadriceps/hamstrings UPDRS Beck Depression Inventory, Parkinson fatigue scale, Parkinson Disease Questionnaire, Falls efficacy Scale | Increased gait speed (+11%, +6%, +9%) (not significant between groups) VO 2 max (+8% groups 1 and 2) 1 RM (quadriceps: +1%, 3%, 15.7%; hamstrings: +4%, 8%, 16%) UPDRS (group 3 only: −3.5 points) No improvement on quality of life, fatigue, depression, fear of falling |

The increase in step length lingered at 4 months post-training .

Thus, strength training seems to be more effective than other types of physical training techniques on gait parameters and aerobic capacities. No study focused on interval training. In most studies exercise intensity increased progressively but was handled very differently from one study to the next.

1.6.2.4.3

Intensity

Studies that compared high intensity (power training at 80% of maximum capacities) vs. low intensity (endurance training at 50% of maximum capacities) reported the following ( Table 5 ):

- •

after a 30-minute session, the improvements in gait speed and step length were similar for high and low intensity training programs ;

- •

after 8 to 10 weeks of strength training:

- ∘

the improvement in UPDRS score was greater after high intensity training, but results were not always significant ,

- ∘

similar increase in VO 2 max in both groups ,

- ∘

improvements in gait speed, step length, height and symmetry were significantly greater after high intensity training for Fisher et al. yet these results were not found by Shulman et al. .

- ∘

| Study | Population recruited | Training protocol | Inclusion criteria | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pohl et al. (2003) | 17 patients with PD stages I–III H&Y | 4 groups, one 30-min session in each group over 4 consecutive days Treadmill with increments: beginning at a comfortable speed, then +10%/10 s Treadmill without increments: at a comfortable speed Physical therapy group: functional gait exercises Control group: sitting on a chair | T10m | Significant improvements for speed and step length in the first 2 groups (+0.2 m/s and +0.17 m/s, +0.07 m, +0.06 m) ( P < 0.001), not significant increase in the 3rd group (+0.04 m/s, +0.01 m), no increase in the control group No significant difference between the 1st and 2nd group |

| Fisher et al. (2008) | 13 patients with PD stages I–II H&Y | 3 groups, 24 sessions over 8 weeks High intensity group: treadmill with 10% body unloading, effort intensity > 3 METs or 75% theoretical HRmax. Progressive increments according to tolerance Low intensity group: physical therapy associating gait, balance exercises and stretching: intensity < 3 METs Control group: therapeutic education | UPDRS Gait biomechanics analysis Transcranial magnetic stimulation | Improvement on the UPDRS score in the first 2 groups (−3 points and −5 points) without any significant difference between groups Higher increased in group 1 for length (+0.04 m and +0.01 m), height (+0.02 m and + 0.01 m), as well as gait speed (+0.1 m/s, +0.02 m/s) (no P ) Better corticomotor excitability in group 1 |

| Ridgel et al. (2009) | 10 patients with PD stages I–III H&Y | 2 groups, 3 sessions of 1 hour (5 min pause every 20 minutes) during 8 weeks “Forced” group: biking on a cycling ergometer at 130% of their “comfortable” HR; 5% increments every 2 weeks “Voluntary” group: biking at their comfortable HR. Same increments | VO 2 max UPDRS III | Increase of the VO 2 max: +17% in group 1, 11% in group 2. No significant difference between groups Improvement in UPDRS III, significantly higher in group 1: +31% in group 1, +5% in group 2 (not significant). Lingering effects at 4 weeks post-intervention |

| Schenkman et al. | 67 patients with PD stages I–III H&Y | 3 groups: 3/weeks for 3 months High intensity (23 patients): beginning at 50% HRR during 15 min, 5 min increase every 2 weeks, +0.2 km/h, +1% slope, up to 30 min efforts at 70–80% HRR Low intensity (22 patients): beginning at comfortable speed, 0% slope, 15 min, 5 min increments every 2 weeks, up to 50 min at 40–50% HRR Stretching and muscle resistance training (22 patients): 2 series of 10 repetitions, increased resistance according to tolerance | T10m VO 2 max 1RM quadriceps/hamstrings UPDRS Beck Depression Inventory, Parkinson fatigue Scale, Parkinson Disease Questionnaire, Falls efficacy scale | Increased gait speed (+11%, +6%, +9%) (not significant between groups) VO 2 max (+8% groups 1 and 2) 1 RM (quadriceps: +1%, 3%, 15.7%: hamstrings: +4%, 8%, 16%) UPDRS (group 3 only: −3.5 points) No improvements on quality of life, fatigue, depression, fear of falling |

Nevertheless, in this last study training time was greater in the high intensity group than in the low intensity one.

1.6.2.4.4

Session frequency

No study has compared two different training frequencies; in most cases the sessions took place 3 times a week and lasted between 45 minutes and one hour, this frequency was well tolerated by the patients event at a moderate or severe stage of the disease .

1.6.2.4.5

Timetable of the sessions

Only one study has evaluated the effectiveness of one strength training session on a motorized cycle ergometer (Motomed) in 10 patients with PD in the OFF phase (Stages I to III on the Hoehn and Yahr scale), which lasted 40 minutes at 70% of the theoretical HRmax: after the session the motor UPDRS had decreased with improvements notably on tremor and rigidity . There was no control group.

1.6.2.4.6

Program duration

The review by Herman et al. reported 3 studies for which the training-related improvements on gait parameters were significant after one single session .

In average, the duration of strength training protocols used in the different studies was 10 weeks. A study lasted 16 months: 3 days per week for 4 months, followed by once a month for 12 months: at M4 the authors noted significant improvement in gait parameters, balance, VO 2 max, UPDRS and quality of life, at M16 only the improvements in VO 2 max had lingered .

Frazzita et al. have studied the relevance of renewing a strength training program at a distance : 50 patients with PD participated in a 4-week program associating 1 hour of muscle resistance training, 1 hour of balance training on a stabilizing platform and 1 hour of transfer, turning and grasping exercises. The same program was renewed one year later. Evaluation criteria were the motor section of the UPDRS score and L-dopa daily dosage. In average the initial UPDRS motor score was at 14 and had significantly decreased after 4 weeks (mean score at 9). At one year, the mean UPDRS motor score was 14 and after a new 4-week program it had gone down to 11. This group was compared to a control group, which had an initial score at 14 and at one year it had increased to 19. The effects of strength training had thus faded over time, but a second program one year later stabilized the progression with a potential reversibility, contrarily to the control group.

Daily doses of L-Dopa had decreased in average by 52 mg per day in the first group ( P = 0.04), and increased by 30 mg in the second group ( P = 0.015).

Of course this single study on 50 patients did not include solely strength training exercises, yet it seems interesting to renew a rehabilitation protocol.

1.6.2.4.7

At home or in rehabilitation centers

Schenkman et al. compared 3 different rehabilitation approaches: global functional training and balance exercise, supervised aerobic training on a cycle ergometer and home training independently (stretching and muscle resistance training) with 1 session/month supervised by a physiotherapist, for 16 months. Functional improvements were lower in the third group. There was no control group . Nieuwboer et al. assessed the effectiveness of a home training protocol for gait parameters based on auditory cues. The authors reported improvements in gait and posture with decreased freezing, increased gait speed and step length, however these improvements did not linger at 6 weeks .

1.6.2.4.8

Group training or individual training

Group training could promote socializing and motivation of patients. No study has compared group training vs. individual training. In a study, by Guo et al., not specific to strength training, patients reported subjective improvements of motor symptoms and quality of life without objective improvements on quantitative measurements taken in the group rehabilitation programs .

1.6.3

Discussion: limits and feasibility

Strength training yields functional benefits in patients with PD, with improvements in aerobic performances, muscle strength, gait parameters, posture and balance. In several studies, these improvements have a positive impact on the quality of life of patients . Results vary however regarding its impact on the number of falls, cognitive functions and depression. Even though the incidence of the disease seems lower in patients who exercised regularly, the impact of strength training on the disease progression has not yet been validated in spite of the neuroprotective effect suggested in animal models of the disease. However, in their study Frazzita et al. found a stability of the UPDRS motor score at one year after two strength training sessions, suggesting a positive effect of strength training on the disease progression, which needs to be validated by further studies.

Most studies were randomized controlled studies. Few studies have compared the strength training group to a control group with no rehabilitation care at all, which might reinforce the hypothesis of some yet undemonstrated benefits. Most times, the control group had some type of rehabilitation care: in some studies training frequency was not identical in both groups, thus inducing a potential bias. Furthermore, the type of rehabilitation strategy was not always indicated making interpretation quite difficult sometimes.

In all studies, cognitive disorders were an exclusion criterion (most often MMS < 26/30). The population included was most often at a mild or moderate stage, patients were in the ON phase during rehabilitation training. Thus, the data cannot be generalized to the entire population of patients with PD.

Finally, very few studies have evaluated the positive impact of strength training on the long term.

One study evaluated the durable effect of the improvements at 16 months, only the VO 2 max improvements lingered . Patients did not retain the initial improvements on the other parameters (gait, balance, UPDRS and quality of life). The tolerance of these programs seems quite good, with a satisfactory compliance in average, however it is important to note that the studies included mostly highly motivated patients, with no cardiopulmonary pathologies (exclusion criterion) thus limiting the risks of complications.

In light of the literature, it is quite difficult to refine the nature of a unique protocol to be implemented in clinical practice.

1.6.3.1

According to the patient

It seems relevant to beginning a strength training protocol as early as possible in the evolution of the disease. Even if its impact on slowing down the disease’s progression remains uncertain, the neuroprotective effect validated in animal models could be valid in humans. At an advanced stage of the disease, the issue of conducting a strength training protocol is still being debated: according to the patient’s limited motor capacities at this stage, the only protocols conducted use a harness to maintain the patient upright, underlying the patient’s need for safety and essential precautions needed for this type of rehabilitation care protocol. The question of the training timetable is still up in the air since very few studies have been conducted during the OFF phase, training during the ON phase has been suggested to facilitate and optimize exercise sessions . However, this issue is actually being debated, with a potential relevance for working during the OFF phase which could promote a better access to endogenous dopamine and thus increase the delay before taking the first dose of L-Dopa .

1.6.3.2

According to strength training parameters

Most studies report continuous training with progressive intensity increments, performed very differently from one study to the next and not always precisely described, rendering its practical application quite difficult to implement. In the absence of comparative studies, it is also complicated to refine which type of ergometers should be used. Treadmill training seems to yield good results, but studies comparing it to functional gait exercises (gait pattern) do not detail the modalities of the latter, thus potentially limiting the interpretation of its results. Its action mechanism also needs to be refined; the treadmill gait of a healthy subject is similar in characteristics to the gait of a patient with PD with shortened step length and increased gait speed . A muscle resistance training component for the lower limbs should be added (60–70% 1RM): quadriceps, hamstrings and foot extensors. To date, high-intensity training protocols seem to yield more improvements than low-intensity training ones, but one recent study reported contradictory results , which prevent us from drawing a conclusion. Most studies used 3 sessions per week and this training schedule appears appropriate. The duration of the training protocol varies from one study to the next but averages 10 weeks. It seems interesting to continue this type of rehabilitation training on the long term, or repeated over time, for example once a year. Group or home training protocols would be interesting to promote the regularity of strength training.

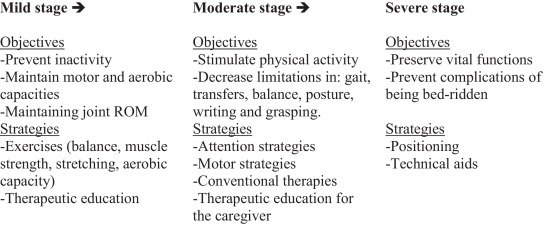

In any case, the practical implementation of a training protocol must be associated with conventional motor rehabilitation strategies guided by the stage of the disease ( Appendix 1 ).

1.7

Conclusion

In spite of therapeutic advances, Parkinson’s disease is severely debilitating for patients especially on a motor level. The effectiveness of several rehabilitation care techniques has been validated. Strength training does bring real improvements in patients with PD and must become an integrated part of the care management in this pathology, even more so since it is very well tolerated. It should be started in the early stages of the disease, last for several weeks, and be repeated over time. It should associate exercises on a cycle ergometer or treadmill with global muscle resistance training.

However, several questions remain unanswered, such as recommended exercise intensity and timetable (ON or OFF phase), thus further studies are required to facilitate the practical implementation of this type of strength training in clinical settings.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Appendix 1

Rehabilitation objectives and strategies according to the disease’s stage.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La maladie de Parkinson idiopathique (MPI) est une affection dégénérative du système nerveux central, d’étiologie inconnue, différenciée des syndromes parkinsoniens qui sont secondaires à des mécanismes infectieux, toxiques, traumatiques, vasculaires, tumoraux, et des syndromes parkinsoniens « plus » (atrophie multisystématisée, paralysie supranucléaire progressive, dégénérescence cortico-basale et démence à corps de Lewy). La MPI est l’affection neurodégénérative la plus fréquente après la maladie d’Alzheimer. Malgré les avancées thérapeutiques médicamenteuses, elle provoque des incapacités et un handicap souvent sévère. C’est la deuxième cause de handicap neurologique après l’accident vasculaire cérébral. Avec le vieillissement de la population et sa prévalence croissante, l’organisation des soins autour de cette pathologie devient un enjeu de santé publique. La prise en charge rééducative des patients parkinsoniens s’est beaucoup développée ces dernières années, en particulier sur le plan moteur et sur le langage. Les techniques employées doivent être adaptées au stade de la maladie. Basée sur des expériences chez l’animal, le réentraînement à l’effort chez les patients parkinsoniens a récemment pris une place importante dans le programme de soins rééducatifs. Plusieurs études récentes contrôlées randomisées mettent en avant ses effets bénéfiques. Cependant, l’hétérogénéité des paramètres d’exercice et des patients inclus rend au premier abord leur application pratique au quotidien difficile pour les thérapeutes.

Les objectifs de ce travail sont, au vue des données actualisées de la littérature, d’une part de préciser l’intérêt du réentraînement à l’effort au cours de la MPI et d’autre part d’essayer d’en déterminer les modalités pratiques.

2.2

La maladie de Parkinson : échelles d’évaluation

Plusieurs échelles d’évaluation clinique des patients souffrant de la maladie de Parkinson ont été validées, utiles lors des évaluations thérapeutiques :

- •

des échelles d’évaluation globale comme l’échelle de Hoehn et Yahr , peu sensible mais fiable, permet une classification des patients en 5 stades ;

- •

les échelles d’évaluation analytique, appréciant l’intensité de chaque signe clinique (échelle de Webster par exemple) ;

- •

les échelles fonctionnelles mesurant les conséquences de la maladie de Parkinson dans la vie courante (PDQ-39 ) ;

- •

les échelles multidimensionnelles permettant le mieux d’appréhender la situation réelle des malades, la plus utilisée étant l’échelle UPDRS (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale) . La section III (examen moteur), dès la phase initiale de la maladie, permet d’en suivre l’évolution et d’adapter le traitement. Elle est également une aide au diagnostic puisqu’une amélioration du score de plus de 50 % 3 à 5 ans après la mise en route du traitement dopaminergique oriente vers le diagnostic de MPI ;

- •

les échelles génériques explorant plus spécifiquement les fonctions cognitives, psychiques, fluctuations motrices.

L’évolution de la maladie de Parkinson se fait en trois phases : la phase de « lune de miel » (1 à 8 ans) durant laquelle le traitement médicamenteux est particulièrement efficace ; la deuxième phase, en moyenne 4 à 5 ans après le début de la maladie, durant laquelle se développent les complications motrices de la dopathérapie (akinésie de fin de dose, phénomènes ON-OFF, dyskinésie de milieu de dose, dyskinésie biphasique) ; la troisième phase, dite avancée ou de déclin, durant laquelle le traitement dopaminergique n’est plus efficace avec prédominance des signes moteurs axiaux (troubles de posture, équilibre, chute, dysarthrie/dysphagie), troubles cognitifs/comportementaux et troubles dysautonomiques.

2.3

Techniques de rééducation motrice conventionnelle utilisées chez le patient parkinsonien

Plusieurs techniques physiques ont fait la preuve de leur efficacité et sont utilisées en pratique clinique dans la prise en charge des patients atteints de la MPI. Leur choix doit être guidé par le stade d’évolution de la maladie.

2.3.1

Étirements et renforcements musculaires

Le renforcement musculaire des quadriceps, ischio-jambiers et releveurs de pied améliore la bradykinésie, la rigidité musculaire, les paramètres de marche et d’équilibre . Dans la MPI, un déséquilibre se créé entre les muscles agonistes ouvreurs du corps (extenseurs, supinateurs, rotateurs externes, abducteurs des ceintures scapulaire et pelvienne) et les muscles antagonistes fermeurs (fléchisseurs, pronateurs, rotateurs internes, adducteurs), comme l’attestent les difficultés objectivées pour les mouvements alternatifs rapides en prono-supination ou flexion-extension . La prise en charge kinésithérapeutique doit privilégier le travail associant un étirement passif des muscles fermeurs et un renforcement des muscles ouvreurs . Un travail de mobilisation axiale active permet de lutter contre la rigidité touchant notamment le tronc. Des séances de Tai Chi peuvent être proposées, diminuant ainsi les troubles de l’équilibre .

2.3.2

Stratégies attentionnelles

2.3.2.1

Stratégies cognitives

Il a été démontré que la focalisation de l’attention du patient parkinsonien sur la réalisation d’une tâche améliore la réalisation de celle-ci . Les instructions verbales ou « indiçage cognitif » ont été les premières étudiées : par exemple, demander au patient de se concentrer sur la réalisation de grands pas pendant la marche , ou balancer de façon exagérée les bras pendant la marche pour lutter contre la bradykinésie. S’y associent les consignes de planification et répétition mentale du mouvement avant sa réalisation, la concentration sur les mouvements pendant leur réalisation, la séparation d’une tâche complexe en sous-séquences simples. Les situations de double tâche détériorent les performances motrices du patient parkinsonien , et l’apprentissage de leur éviction à un stade avancé de la maladie est recommandé. En revanche, Brauer et Morris, Canning et al. ont montré que le travail en double tâche à un stade léger à modéré, associé à des instructions verbales pour reconcentrer le patient sur sa marche, inversait la détérioration motrice en améliorant les paramètres de marche .

2.3.2.2

Cueing ou indiçage sensoriel

L’utilisation de signaux sensoriels externes, visuels ou auditifs, améliore la performance en augmentant l’attention du patient sur la tâche motrice (marche, demi-tours) et diminue le freezing . Elle permet de privilégier la réalisation de mouvements essentiellement contrôlés par le cortex frontal, et de diminuer le relai qui s’effectue habituellement au niveau des noyaux gris centraux pour les mouvements automatiques, déficitaires chez le patient parkinsonien . Peuvent être cités par exemple l’utilisation d’un métronome ou « taper des mains » pour rythmer les pas, les lignes horizontales au sol que le patient doit passer à chaque pas.

2.3.3

Stratégies motrices

Des stratégies motrices sont proposées pour le maintien de la facilité et de la rapidité du geste, comme la réalisation de mouvements de grande amplitude , et des exercices variés, répétés et orientés vers une activité quotidienne précise permettant d’optimiser cet apprentissage et de faciliter le transfert des progrès dans le quotidien du patient (travail du schéma de marche en faisant varier les distances, le type de sol, la vitesse) . L’apprentissage moteur se réalise en 3 phases, associant les stratégies cognitives et motrices : planification de la tâche, concentration sur les mouvements pendant leur réalisation, et automatisation de l’exécution de la tâche par les stratégies motrices décrites ci-dessus, avec ou sans travail en double tâche .

2.3.4

Stratégies comportementales

Elles sont proposées dans des situations spécifiques, habituellement difficiles pour le patient parkinsonien. Par exemple, pour les épisodes d’enrayage cinétique peuvent être proposés de balancer le poids du corps d’un côté puis de l’autre, chanter, dire à haute voix « allez » .

2.3.5

Autres

D’autres techniques non spécifiques au patient parkinsonien sont régulièrement pratiquées, comme le travail de l’équilibre et des réactions posturales (mise en situation de déséquilibre du patient et apprentissage des stratégies correctrices), travail de coordination global, travail des transferts et des relevers de sol.

Une revue Cochrane réalisée en 2001, regroupant 7 études randomisées contrôlées, avait pour objectif de comparer l’efficacité de diverses techniques de rééducation : indiçage visuel ou auditif, renforcement musculaire associé ou non au travail de l’équilibre, techniques de facilitation neuromotrice, Bobath, relaxation, karaté, étirement : le niveau de preuve s’est avéré insuffisant pour déterminer la supériorité d’une technique par rapport à une autre .

Une autre revue de la littérature publiée en 2012 a étudié l’efficacité de l’intervention des thérapies physiques comparativement à l’absence de prise en charge, incluant 33 essais randomisés contrôlés : un bénéfice à court terme (< 3 mois) était observé pour la vitesse de marche, le relever de chaise, l’équilibre selon l’échelle de Berg, l’incapacité selon l’échelle EEUMP .

2.4

Retentissement cardio-pulmonaire et musculaire de la maladie de Parkinson et de ses traitements

Les patients atteints de la MPI sont pour la plupart âgés et cumulent les effets du vieillissement et ceux de la MPI sur leur aptitude à l’effort.

Avec l’âge, la VO 2 max (témoin de la capacité du métabolisme aérobie à fournir de l’énergie au maximum de l’effort) diminue . Cette diminution est d’origine plurifactorielle associant des facteurs périphériques (musculaires et vasculaires) et centraux (cardiaques et respiratoires). Au niveau musculaire, une réduction de la masse musculaire (sarcopénie) s’installe progressivement . Elle touche particulièrement les fibres rapides de type 2 avec une diminution du nombre et de la taille de ces fibres. S’ajoute une réduction qualitative du muscle résultant en une baisse de la force musculaire. Le deuxième facteur périphérique est le système vasculaire avec une pression artérielle systolique plus élevée au repos et à l’effort (par diminution de la compliance), la pression artérielle diastolique restant elle stable . Au niveau cardiaque, il existe également une baisse de la compliance du ventricule gauche, ainsi qu’une diminution de la sensibilité adrénergique. La combinaison de ces phénomènes entraîne une diminution de la fréquence cardiaque maximale d’effort et une diminution du volume d’éjection systolique d’où un débit cardiaque plus faible. À cela s’ajoute sur le plan pulmonaire une perte de souplesse de la cage thoracique aboutissant à une diminution de la capacité vitale, du VEMS et une augmentation du volume résiduel .

Si le vieillissement s’accompagne physiologiquement d’une réduction de l’aptitude aérobie, il a été démontré que les patients parkinsoniens ont une capacité d’effort maximal inférieure à celle des sujets sains de même âge, en particulier pour les stades modérés à sévères de la maladie . Chez les sujets dont la maladie de parkinson est au stade léger, le niveau de VO 2 max est en revanche similaire . Ces limitations objectivées sur des tests d’exercice sont corrélées à une réduction du niveau d’activité physique par rapport à des sujets sains de même âge . La réduction de l’aptitude à l’effort n’est pas uniquement une conséquence de l’inactivité engendrée par la maladie via l’atteinte motrice. L’atteinte de la voie nigrostriée altère directement les différents éléments centraux et périphériques.

Sur le plan cardiovasculaire, l’atteinte du système nerveux autonome, documentée par la présence de corps de Lewy retrouvés dans les ganglions et axones des chaînes sympathiques et dans les centres ortho et parasympathiques , entraîne une hypotension orthostatique diurne chez environ 20 % des patients , souvent associée à une hypotension postprandiale . Une inversion du rythme circadien de la tension artérielle avec une hypertension en position allongée, donc la nuit, peut également être observée . Ces troubles sont liés aux effets indésirables de certains traitements utilisés pour la MPI (agonistes dopaminergiques, L-Dopa, inhibiteurs de la MonoAmine Oxydase B surtout) mais également à la pathologie elle-même . Les anomalies cardiaques spécifiques semblent rares : il n’a pas été décrit d’anomalie électrocardiographique (ECG) ou de trouble du rythme. À l’effort, peu d’études ont porté sur les différences d’adaptation cardiovasculaire chez le patient parkinsonien versus le sujet sain de même âge. Reuter et al. ont retrouvé une tension artérielle systolique à l’effort plus basse chez les patients parkinsoniens, mais les résultats étaient non significatifs . Palma et al. ont observé une fréquence cardiaque maximale d’effort plus faible chez les patients parkinsoniens, à même intensité d’exercice .

Sur le plan pulmonaire, il existe une prévalence anormale de syndrome restrictif chez le patient parkinsonien , avec des pressions inspiratoires (PI) et pressions expiratoires (PE) plus faibles, et ce dès le stade précoce de la maladie . Différents mécanismes ont été décrits pour expliquer ces anomalies : la déformation de la cage thoracique et du rachis en antéflexion , la rigidité et bradykinésie des muscles respiratoires, conséquence directe de l’atteinte de la voie nigrostriatale .

Sur le plan musculaire, les patients atteints de MPI ne présentent pas d’atteinte spécifique des fibres musculaires, néanmoins les capacités motrices sont moindres en comparaison aux sujets sains de même âge , en partie du fait de la bradykinésie et de la rigidité , interférant avec la réalisation des mouvements .

La prise en charge des patients atteints de la maladie de Parkinson doit donc être globale et tenir compte également des conséquences cardiorespiratoires de cette pathologie pour leur permettre de maintenir des capacités physiques optimales.

2.5

Réentraînement a l’effort et maladie de Parkinson : du modèle animal a l’application chez l’homme

Outre les effets physiologiques démontrés du réentraînement à l’effort sur le muscle (optimisation de la capacité mitochondriale à produire de l’énergie sous forme d’ATP, augmentation en nombre et en taille des mitochondries, optimisation de l’utilisation des substrats énergétiques, adaptation de la typologie musculaire) et sur le système cardiorespiratoire (augmentation de la masse cardiaque, de la volémie, du volume d’éjection systolique et du débit cardiaque maximal, amélioration de l’extraction périphérique en oxygène, meilleur contrôle tensionnel, optimisation des débits sanguins généraux et du contrôle ventilatoire), le modèle animal a permis d’étudier l’effet du réentraînement à l’effort au niveau cérébral, en particulier dans le cadre de la maladie de Parkinson.

Les premiers travaux ont montré que la pratique d’un exercice chez le rat augmentait le taux des métabolites dopaminergiques dans le striatum, faisant évoquer l’utilisation de la dopamine lors de l’exercice physique . D’autres études ont confirmé l’augmentation de la synthèse et de la libération de dopamine suite à l’exercice chez le rat . Par ailleurs il a été démontré chez l’animal que l’exercice induisait une neuroplasticité, une neuroprotection et une augmentation des facteurs trophiques tissulaires .

Les mêmes constatations ont été réalisées chez le sujet sain avec augmentation de la production de dopamine endogène après un exercice physique . Toutefois il n’est pas confirmé que l’exercice chez le patient parkinsonien induit la libération supplémentaire de dopamine et contribue à ralentir la perte progressive des cellules dopaminergiques . Enfin plusieurs études ont retrouvé une amélioration de l’efficacité de la L-Dopa et de son absorption lors d’un effort physique prolongé, par augmentation de la circulation sanguine cérébrale induite par l’exercice .

2.6

Bénéfices et limites du réentraînement a l’effort chez le patient parkinsonien : revue de la littérature

2.6.1

Méthodologie

Une revue de la littérature a été réalisée à partir des moteurs de recherche Pubmed et Cochrane, en utilisant les mots clés suivants : « Parkinson’s disease », « exercise therapy », « aerobic training », « strength training », « treadmill training ». Quatre revues de la littérature, 1 méta-analyse et 31 essais randomisés ont été inclus.

2.6.2

Résultats

2.6.2.1

Effets bénéfiques du réentraînement à l’effort chez le patient parkinsonien

2.6.2.1.1

VO 2 max

La mesure de la VO 2 max avant et après la réalisation d’un protocole de réentraînement à l’effort a été utilisée comme critère d’évaluation dans 4 études ( Tableau 1 ). Sa valeur a été déterminée par réalisation d’une épreuve d’effort, sur cycloergomètre avec une incrémentation en pallier (+25 watts/3 min) dans l’étude de Ridgel et al. , en rampe dans l’étude de Bergen et al. , et sur tapis de marche dans l’étude de Shulman et al. (débutée à vitesse confortable et 0 % de pente, incrémentation par pallier [+2 % de pente par minute]). Dans l’étude de Schenkman et al. , elle a été déterminée à la fin d’une marche de 5 minutes à 4 vitesses différentes. La VO 2 max était améliorée significativement à la fin du programme de réentraînement dans toutes les études, avec un effet persistant à 16 mois dans l’étude de Schenkman et al.