CHAPTER 31

Economic Impact of Spasticity and Its Treatment

Michael Saulino

Health care economics attempts to analyze the factors associated with the efficiency, effectiveness, values, and behaviors associated with the production and consumption of health care. The term health care economics is often credited to Arrow who noted several unique economic features of health care compared with other facets of society (1). Factors that distinguish health care economics include extensive governmental oversight and intervention, high levels of uncertainty, barriers to entry, and the presence of a third-party agent. In health care economic terms, the third-party agent is the clinician, who makes a purchasing decision (eg, prescribes a medication, performs a procedure) while being insulated from the price of the product or service (2). In the era of health care reform, it has become evident that economic evidence is a critical prerequisite to treatment planning (3). The purpose of this chapter is to examine the influence of spasticity and associated treatments on health care costs.

As described more extensively in this textbook, spasticity is a phenomenon that appears in a number of upper motor neuron conditions including spinal cord injury, brain injury, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and stroke. These conditions are quite divergent in onset and course (4). Isolating the costs associated with spasticity from the disease process itself can be quite challenging. Spasticity has the capacity to influence a number of health-related domains including mobility, self-care, caregiver burden, pain, and contracture. This syndrome typically produces both direct and indirect medical costs. Direct costs represent the costs associated with medical resource utilization, which include the consumption of inpatient, outpatient, rehabilitative, and pharmaceutical services within the health care delivery system. The term indirect costs is defined as the expenses incurred from the cessation or reduction of work productivity as a result of the morbidity and mortality associated with a given disease. Indirect costs typically consist of work loss (from either the patient or caregiver), worker replacement, and reduced productivity from illness and disease (5).

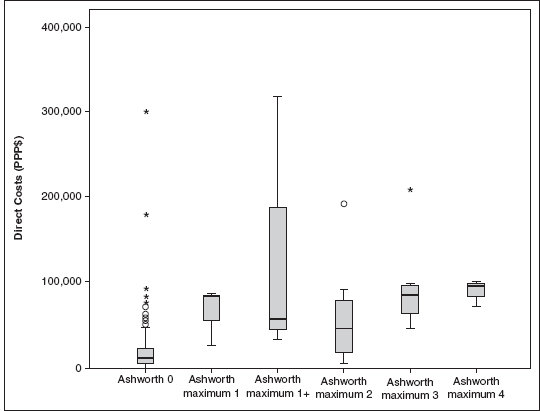

It is a daunting undertaking to ascertain the cost burden associated directly with a spastic condition that is distinct from the expenses of the disease process itself. Lundström et al describe a four-fold increase in direct medical cost of spastic poststroke patients in the first year poststroke compared with nonspastic patients. There was a loose association between spasticity severity (as measured by the modified Ashworth scale) and direct medical costs (Figure 31.1). The main cost driver in this study was inpatient hospitalization costs (6), which indirectly suggests that hypertonicity influences other sequelae of neurologic disease. By extension, effective treatment of spasticity could decrease the incidence and impact of these sequelae. Zettl et al described increasing direct costs in multiple sclerosis patients as spasticity progressed from mild to moderate to severe (7). This finding was similar to that of Svensson et al, who also found increasing costs associated with multiple sclerosis patients as spasticity worsened. The largest cost component in this investigation was direct, nonmedical costs (8). These two multiple sclerosis studies do not compare costs of spastic patients to nonspastic patients. Similar studies are lacking in brain injury, spinal cord injury, spinal cord diseases, and cerebral palsy. This latter group (Svensson et al) recently surveyed health care providers of multiple sclerosis patients to estimate their involvement and the resource use associated with different levels of spasticity. Their results suggested that the level and cost of care substantially increased with the degree of spasticity. Key factors contributing to high annual costs per patient were home care, hospital admissions, and costly items, such as hospital beds and wheelchairs (9).

FIGURE 31.1 Direct costs for stroke by Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) scores. Ashworth maximum 1 stands for a maximum MAS score of 1 in any of the tested joints. A round circle (○) denotes an outlier that is between 1.5 box lengths and 3 box lengths from the end of the box. An asterisk (*) denotes an extreme that is >3 box lengths from the end of the box.

Source: Adapted from Ref. (6). Lundström E, Smits A, Borg J, et al. Four-fold increase in direct costs of stroke survivors with spasticity compared with stroke survivors without spasticity: the first year after the event. Stroke. 2010;41(2):319–324.

Rehabilitative interventions are critical to the management of spasticity both in isolation as well in combination with other treatment modalities described in this textbook. A multitude of different treatment techniques have been reported to modulate muscle overactivity, including range of motion exercises, stretching, therapeutic exercise, constraint-induced therapies, neurodevelopmental techniques, positioning, splinting, neuroprosthetics, serial casting, and functional electrical stimulation. The costs associated with these interventions are primarily the expense incurred on a per-visit basis as well as the costs associated with equipment procurement for home use (such as braces and splints). Many insurance carriers limit the number of therapy sessions that a patient can undergo. Additionally, many payers will only cover a portion of the therapy costs with the residual amount passed to the patient (ie, co-payment or co-pay). This residual payment can be cost prohibitive for many patients (10). There are no studies that specifically delineate the costs of rehabilitative therapy for spasticity specifically as monotherapy. Some of the research studies detailed elsewhere in this chapter describe these costs in a multidisciplinary approach to spasticity management.

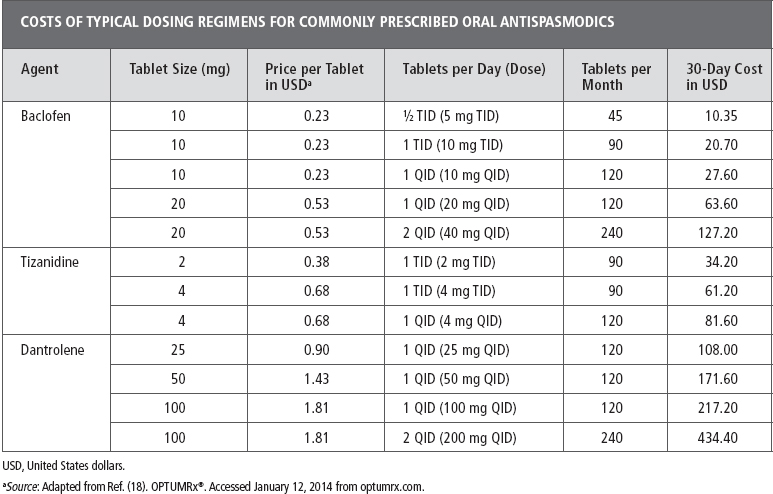

Several oral medications have potential utility as antispasticity agents (11). The most commonly used drugs are baclofen, tizanidine, dantrolene, and diazepam. Advantages of oral medications include appropriateness for multifocal or global hypertonicity, technical simplicity, utility as a “prn” or “as needed” technique, and alternative uses including pain, sleep, and psychopharmacology. Disadvantages of oral medications include tolerability/patient adherence, withdrawal, and dependence. From an economic perspective, the use of oral medications is relatively inexpensive. All of these agents have a U.S. generic formulation, which usually correlates with lower price. Table 31.1 demonstrates the costs of some common dosing regimens. Some of the higher dosing regimens have the potential to incur significant costs. It is reasonable to assume that patients at these higher levels could demonstrate cost saving with interventions that would lower their pill burden. Insurance coverage for these oral medications is typically reasonable although some plans limit coverage to a certain number of pills per month (eg, 120, 180). As opposed to other modalities discussed in this chapter, there are no technical or professional fees associated with oral medication use. It can be assumed that patients who have spasticity warranting treatment would be routinely followed by a clinician skilled in the management of their underlying neurologic disease, such as a neurologist or a physiatrist. As such, there should be minimal added cost for the prescribing of oral medications. Since tizanidine and dantrolene both have the potential for hepatotoxicity, routine assessments of hepatic function are recommended. These laboratory assessments do have the potential to add incremental costs to treatment with these agents. The medical literature has minimal discussion regarding the economic impact of oral spasticity agents. Rushton et al compared the costs associated with baclofen and tizanidine treatment and suggested minimal differences in costs between the two drugs (12). As for other oral agents, Sativex, a cannabinoid oromucosal spray containing a 1:1 ratio of 9-δ-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), has received approval in many countries for treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis when conventional antispastic therapy is not adequately effective. There are ongoing clinical trials of this preparation in the United States (13). There is some suggestion from economic analysis that this treatment can be a cost-effective approach although some models are less favorable (14–16). As other oral agents become available, a cost–benefit analysis will undoubtedly be necessary (17).

TABLE 31.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree