Distal Tibial Osteotomy

J. Eric Gordon

DEFINITION

Angular deformities of the distal tibia can lead to varus or valgus malalignment of the ankle joint.

Rotational deformities of the tibia include both internal and external tibial torsion.

Additional sources of ankle malalignment include both bony and ligamentous disorders.

ANATOMY

The tibiotalar joint is normally oriented perpendicular to the long axis of the tibia. This is assessed by measuring the lateral distal tibial angle (LDTA), which has a normal value of 90 degrees (range, 88 to 95 degrees).

Sagittal alignment of the ankle joint is in slight dorsiflexion and is assessed by measuring the anterior distal tibial angle (ADTA), which has a normal value of 80 degrees (range, 78 to 81 degrees).

Rotational alignment of the tibia changes with age. Internal tibial torsion is common after birth and gradually corrects until approximately age 5 to 6 years. The normal thigh-foot angle after age 6 years is 0-15°.

PATHOGENESIS

Coronal plane deformities about the ankle are not uncommon and may occur secondary to congenital or acquired conditions.1, 2, 3

Varus angular malalignment of the ankle is generally due to either a traumatic or infectious insult to the medial aspect of the distal tibial physis, with resultant premature closure of the injured area and relative overgrowth of the lateral distal tibial physis and fibula with resultant progressive varus.2, 3, 7

Valgus deformity of the ankle in children is caused by a wide variety of congenital and developmental as well as posttraumatic conditions.

Neuromuscular conditions such as diplegic cerebral palsy can lead to foot pronation, and late ankle valgus and progressive ankle valgus with lateral wedging of the distal tibial epiphysis may be seen in patients with myelodysplasia.

Traumatic or postinfectious injury to the distal fibular or lateral distal tibial physis can produce distal tibial valgus.

Congenital fibular hemimelia is often associated with distal tibial valgus which can be exacerbated by hindfoot coalitions leading to severe hindfoot valgus.

Congenital pseudarthrosis of the fibula can often lead to ankle valgus as well.

Iatrogenic distal tibial valgus with fibular shortening can also occur following fibular harvest for vascularized or nonvascularized bone graft.

Deformities occurring secondary to physeal injuries are progressive until skeletal maturity.

Correction of deformities about the ankle is complicated by the fact that deformities are frequently centered about the distal tibial physis, very close to the ankle joint, and opening or closing wedge osteotomies performed proximal enough to allow fixation of the fragments can produce secondary deformities with unacceptable translation of the ankle joint.

NATURAL HISTORY

Angular deformity of the distal tibia leads to abnormal loading of the hindfoot, ankle joint, and knee and may lead to secondary deformities such as a planovalgus foot or hallux valgus. Long-term malalignment of the ankle joint may lead to the development of premature osteoarthritis of the ankle.8, 9

Initially, the limb may be treated with braces or orthotics relieving pain and correcting gait, but progression of the deformity with growth can lead to increased soft tissue pressure, bursa formation, and skin ulceration over the medial malleolus, lateral malleolus, or talonavicular region.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A detailed history should be obtained, including recent or remote trauma, infection, or congenital conditions. In addition, symptoms related to ankle malalignment or instability should be elicited.

Physical examination should include gross inspection of both lower extremities with the patient standing, walking, and sitting to determine the location of deformity as well as the alignment of adjacent structures (in particular, the hindfoot and knee) that may contribute to perceived deformity as well as affect the surgical outcome.

The orthopaedic surgeon should inspect standing foot and ankle alignment from behind the patient to determine the location of deformity (distal tibia, ankle, hindfoot).

Standing heel alignment in varus or valgus may indicate the presence of uncompensated distal tibial deformity. Normal alignment in the presence of known deformity should alert the surgeon to hindfoot compensation, which may be rigid or supple.

The orthopaedic surgeon should check hindfoot passive inversion and eversion to evaluate the ability of the hindfoot to accommodate surgical changes.

Lack of hindfoot motion indicates that the patient may not be able to compensate for distal tibial osteotomies. Further procedures may be warranted to realign the hindfoot to correct fixed deformities.

Single-limb toe rise: With the patient standing, viewed from posterior, the patient lifts one limb, then rises onto the toes

of the standing limb. This should result in prompt inversion of the heel, rising of the longitudinal arch, and external rotation of the supporting leg. Lack of hindfoot inversion should draw attention to the subtalar and transverse tarsal joints as possible sites of pathologic alignment.

To check forefoot-hindfoot alignment, the patient is seated, facing the examiner. The patient’s hindfoot is grasped in one hand and the calcaneus is held in the neutral position, in line with the long axis of the leg. The examiner’s other hand grasps the foot along the fifth metatarsal. The thumb of the hand grasping the heel is placed over the talonavicular joint, and the joint is manipulated by moving the hand holding the fifth metatarsal until the head of the talus is covered by the navicular. The position of the forefoot as projected by a plane parallel to the metatarsals is compared to the orientation of the long axis of the calcaneus. The forefoot will be in one of three positions relative to the hindfoot—neutral, forefoot varus, or forefoot valgus. The examiner should determine whether this relation is supple or rigid, especially when considering surgery because a fixed varus or valgus forefoot deformity will not allow the foot to become plantigrade after realignment of the tibiotalar or subtalar joints.

Standing lower extremity alignment: If distal tibial deformity is present in conjunction with genu varum or valgum, the patient’s entire deformity should be evaluated and a comprehensive plan developed.

The patient’s gait may show an antalgic pattern or may reveal limitations of functional motion in the hindfoot.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

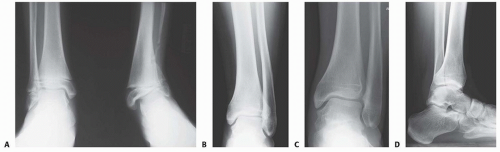

Standing anteroposterior (AP) and mortise views of both ankle joints should be obtained (FIG 1A-C). The LDTA is measured from the intersection of a line drawn parallel to the long axis of the tibia and a second line drawn across the dome of the talus. The normal LDTA is 90 degrees as measured from the lateral side. The amount of deformity is calculated from the number of degrees that differ from 90 degrees.

Lateral weight-bearing radiographs of both ankles should be obtained to detect any sagittal plane deformity (FIG 1D). The lateral tibiotalar angle is measured from the anterior side. The average ADTA is 80 degrees as measured from the anterior side.

Foot radiographs, including standing AP, standing lateral, and oblique views, are used to evaluate hindfoot alignment to avoid over- or undercorrection at the time of surgery. The standing lateral view of the foot is used to evaluate talar-first metatarsal alignment; normally, the talus and first metatarsal are parallel. The standing AP view is used to evaluate the talocalcaneal angle; if the talocalcaneal angle exceeds 35 degrees, hindfoot valgus is present.

A standing AP view of the pelvis is obtained to evaluate for leg length discrepancy.

Computed tomography can be useful in assessing the presence and size of physeal bars.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In addition to distal tibial angular deformity, varus or valgus malalignment about the ankle joint may be due to other local bony or ligamentous disorders.

Fixed hindfoot varus or valgus may simulate ankle deformity on clinical examination.

Apparent ankle valgus may occur secondary to disorders such as angular deformity of the fibula with shortening and associated lateral shift of the talus hindfoot valgus, hindfoot valgus, or fixed forefoot varus.

Apparent ankle varus may occur secondary to disorders such as hindfoot varus as seen in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, residual clubfoot, or fixed forefoot valgus.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Mild distal tibial angular deformity associated with ankle varus or valgus can be managed through the use of custom braces and orthotics or medial or lateral posting of the shoes.

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment of bony deformity of the distal tibia.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

An opening or closing wedge supramalleolar osteotomy (SMO) may be performed for simultaneous correction of frontal and sagittal plane deformities of the ankle.

SMOs allow for immediate correction of the deformity. However, they are considered technically demanding and relatively invasive and require a period of limited weight bearing or non-weight bearing and immobilization.

The challenge involved in correcting varus or valgus deformities of the ankle is to correct the deformity without introducing new secondary deformities. The mechanical axis of the tibia should pass through the center of the ankle perpendicular to the joint surface.

Some SMO techniques may lead to the development of secondary deformities. For instance, a transverse closing wedge osteotomy performed 4 cm proximal to the joint surface to correct a valgus deformity causes lateral shift of the ankle and a prominent medial malleolus.

In a child with growth remaining, physeal modulation via a hemiepiphysiodesis with an eight-hole plate, transphyseal screw, or staples can be used to correct distal tibial valgus deformities.

Correction occurs gradually after hemiepiphysiodesis, so it is not ideal for patients requiring acute corrections such as those with skin breakdown or significant pain. Close follow-up after hemiepiphysiodesis is essential to avoid overcorrection.

Currently, SMOs are the procedure of choice for correcting ankle valgus in the absence of adequate growth to correct the deformity by hemiepiphysiodesis techniques.

Choosing the Technique

Several techniques have been used and are described in the following text, including transphyseal SMO, transverse SMO with translation, and the Wiltse SMO.

Oblique supramalleolar opening or closing wedge osteotomy

Lubicky and Altiok3 described an oblique distal tibial osteotomy to correct varus and valgus deformity of the distal tibia.

This technique offers the advantage of placing the hinge of the osteotomy at the level of the deformity and thus performing the correction at the site of the deformity so that maximum correction can be obtained without creating a secondary translational deformity.

Transverse SMO with translation: Concomitant fibular osteotomies are performed to allow for compression at the osteotomy site and translation of the tibial osteotomy.

Wiltse osteotomy

Wiltse10 noted that a simple wedge resection for correction of distal tibial valgus deformities will lead to malalignment and prominence of the medial malleolus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree