Displaced Scaphoid Waist Fractures

10.1 Introduction

Scaphoid fractures are infamous for troublesome healing. It is notorious that a common fracture in young active adults, representing 2% to 7% of all fractures, of one of the smallest bones presents some of the greatest challenges to physicians involved in trauma care. Up to 55% of nonoperative treatment failures and nonuniting scaphoid fractures often progress to a degenerative collapse of the carpal bones in the wrist. The so-called SNAC (scaphoid nonunion advanced collapse) wrist generally requires a complex salvage procedure such as fusion of the wrist. Consequently, an extremely careful approach to the scaphoid fracture is generally adopted.

Historically, fractures of the scaphoid have not been recognized for very long in comparison with other injuries. It was not until the end of the 19th century that the pathology was first described. The topic rapidly gained popularity in the early 20th century because of the fractures’ unfavorable prognosis and relative frequency. At that time, scaphoid fractures were considered an unsolvable and economically important problem. Treatment had been the subject of long controversy in the medical literature. Advances in treatment took a leap in 1954, when McLaughlin introduced open reduction and internal fixation of the scaphoid. He founded some of the main treatment principles of the current practice. Notably he concluded that “with perfections in operative technique, internal fixations may become the treatment of choice for displaced and unstable fractures of the carpal navicular.” That prediction closely reflects the current practice.

Recent scientific advances have helped us identify the patients with “troublesome fractures.” There is increasingly strong evidence that fracture displacement is the key predictor of healing problems with nonoperative treatment as it is the factor most strongly associated with nonunion in scaphoid waist fractures. While scaphoid waist fractures have a 90% to 95% union rate overall, fractures with greater than 1 mm of displacement are associated with high rates of nonunion, up to 55%. Hence, operative treatment is generally advised for displaced scaphoid fractures. Displaced scaphoid fractures are relatively uncommon, with percentages ranging between 5% and 30% at the waist and an average of 15%.1 The main current issue is to find an accurate, reliable, and simple means of diagnosing scaphoid fracture displacement and instability.

10.2 Diagnosis

While the diagnosis of displacement is a critical factor in the management of scaphoid fractures, it remains a subtle challenge of diagnostic accuracy and definitions vary. Cooney and coworkers defined the displacement of a scaphoid fracture as (1) a fracture gap larger than 1 mm on any radiographic projection, (2) a scapholunate angle larger than 60°, or (3) a radiolunate angle larger than 15°. Amadio et al2 added the criterion that the intrascaphoid angle should not exceed 35°, although this has proven to be unreliable. The criterion for displacement that has been most widely applied is a fracture gap or translation larger than 1 mm. Some authors distinguish between nondisplaced, minimally displaced (defined as displacement equal to or smaller than 1 mm), and displaced scaphoid fractures (larger than 1 mm). The category of minimally displaced fractures represents the greatest inconsistency in the literature, as some consider them nondisplaced while others consider them displaced. The heterogeneity in definitions and diagnostic methods make the interpretation and comparability of studies much more difficult, and the evidence less reliable.

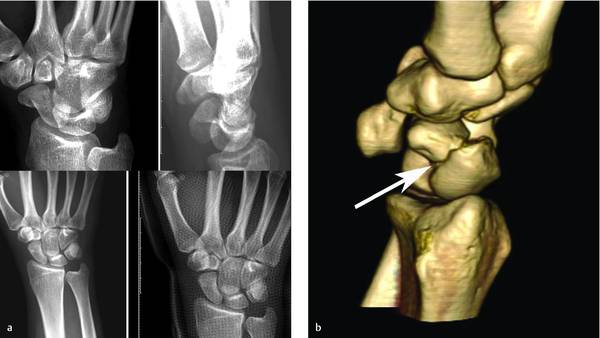

The diagnosis is best made by computed tomography (CT) scanning in the plane of the longitudinal axis of the scaphoid, with reconstructions in the coronal and sagittal planes. Several studies have consistently shown that CT is superior to radiography (▶ Fig. 10.1). However, when compared with arthroscopic visualization as a reference standard, neither radiographs nor CT scans are very accurate at diagnosing displacement of acute scaphoid waist fractures.3 Alternatively, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with reconstructions in the plane of the scaphoid has also been shown to be more reliable at diagnosing displacement of a scaphoid fracture than radiography.4 Many authors suggest that all fractures of the scaphoid, and particularly waist fractures, should be assessed with a CT or MRI scan along its longitudinal axis.

Fig. 10.1 Displacement of a scaphoid fracture may be less apparent on radiographs (a) than on a 3D reconstruction of a CT scan (b).

Three methodological studies showed poor to moderate levels of interobserver reliability for diagnosing displacement.5 In an attempt to improve interobserver reliability, Buijze et al simplified the definition of a displaced scaphoid fracture as anything more than a crack (i.e., any translation, gapping, or angulation).6 They showed a small but significant difference in the interobserver reliability for displacement ratings in favor of the group of observers who were instructed with this definition as opposed to a group who were not. The average sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy also slightly improved. However, levels of interobserver reliability remained moderate.

Computed tomography has the advantage that the type of displacement can be assessed more accurately. Using three-dimensional CT, Nakamura et al identified two types of displaced fractures.7 There is a volar type in which the distal fragment was angulated toward volar, creating a humpback deformity. This type was associated with axial rotation. In the dorsal type, the distal fragment translated toward dorsal and was often associated with a humpback deformity as well. Distal fracture location was associated with the volar type. Theoretically, an acute scaphoid fracture distal to the apex on the dorsal ridge could result in flexion of the distal fragment, because the apex coincides with the attachment of the dorsal intercarpal ligament and the dorsal part of the scapholunate interosseous ligament, both important stabilizers of the scaphoid. Another study that looked at the influence of fracture location and characteristics found no such relationship based on arthroscopic diagnosis of displacement.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree