I. LOW BACK PAIN. Low back pain is ubiquitous in the population, with 50% to 90% of persons having back pain at some point in their lives, and with an annual incidence of 15% to 40%. It is the most common cause of activity limitation in persons younger than 40 years. Fortunately, most patients with back pain will improve with time and will not require extensive studies beyond a good history and physical examination. However, it is important for the clinician to identify patients for which a more urgent or advanced evaluation is needed.

A. History taking in the patient with low back pain. A thorough history is important in determining the etiology of back pain. Important elements of the history are listed in Table 13-1. These elements derived from the history can collectively indicate a specific diagnosis.

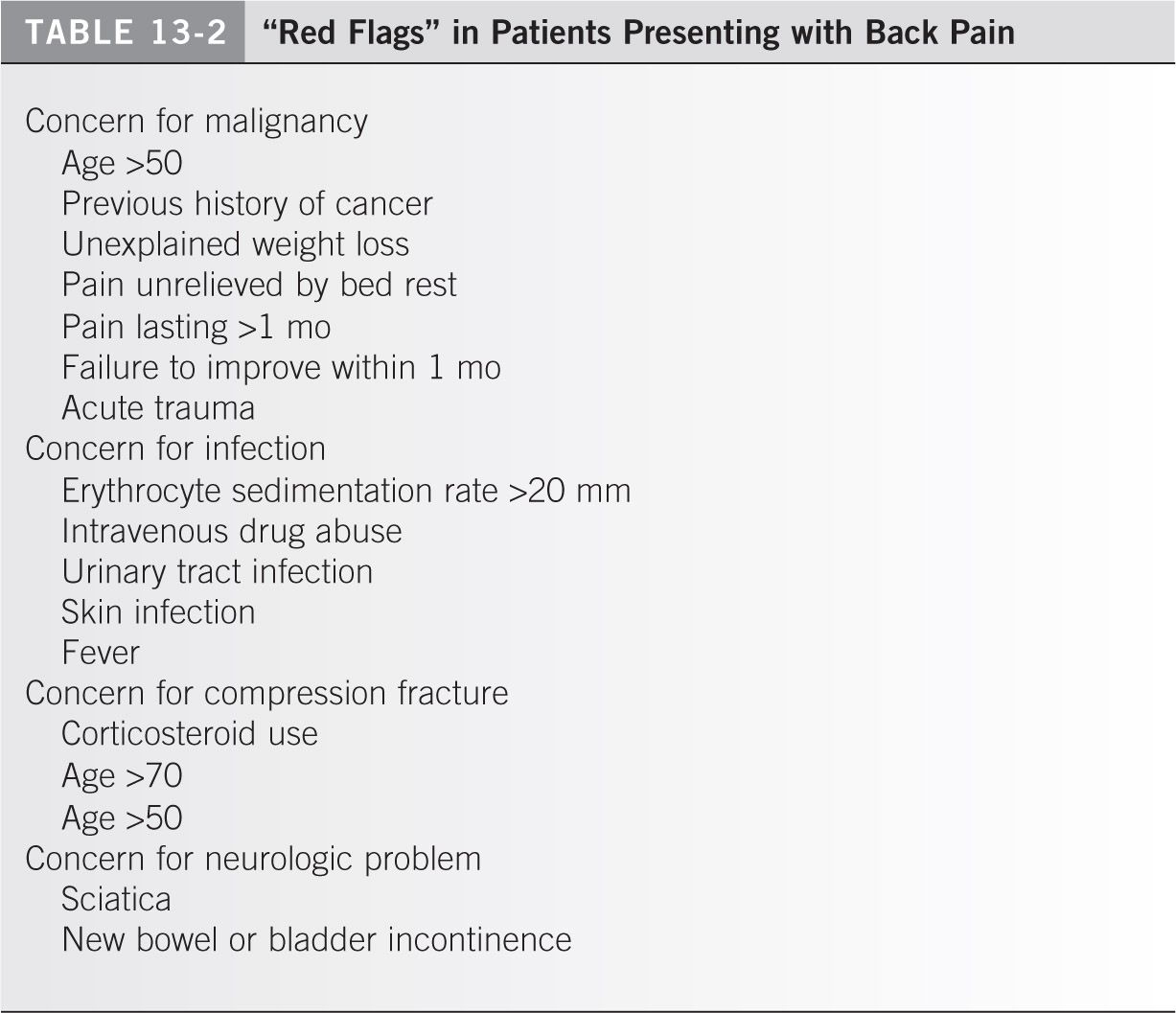

Although the common causes are benign and self-limiting, it is extremely important to be aware of “red flags” and rule out the dangerous causes that require urgent and advanced evaluation (Table 13-2). These red flags include progressive neurologic deficits, night pain, pain at rest, fever, and loss of bowel or bladder control. The common patient with back pain is between the ages of 20 and 50 and has no signs or symptoms of systemic illness. Be on the alert for back pain in the young and the old. A history of night sweats, fever, weight loss, and fatigue may be indicative of a malignancy or an infection. It is also important to elicit any past low back injuries and family history of back problems and to determine forms of treatment that the patient has received and their effects on the pain, as these may provide diagnostic clues.

B. Physical examination. The physical examination complements a good history in the process of arriving at a differential diagnosis. The examination begins with observing the patient’s gait as well as the body position chosen by the patient (patients with acute sciatica may choose to avoid sitting in a slouched position, as this places extra pressure on the impinged nerve root). The back should be exposed, and one should look for any redness or warmth and hairy patches or skin defects. The presence of muscle atrophy or asymmetry should also be noted. Next, the range of motion of the spine is tested. Pain that is aggravated by flexion generally indicates a disc problem, whereas pain that is aggravated by extension points to stenosis, facet arthritis, or spondylolysis. Palpation should then be performed. Spinous process tenderness may indicate an acute osteoporotic fracture, whereas tenderness in the area of the posterior superior iliac spine indicates pain from the sacroiliac joint. A palpable step-off between the spinous processes indicates a spondylolisthesis. A complete motor and sensory examination including deep tendon reflex testing is essential. Dermatomal sensory deficits and muscle weakness may show a pattern indicating impingement of a specific nerve. A straight leg raise is generally performed with the patient in the supine position, but can be done first with the patient in the seated position when the patient’s physical symptoms seem disingenuous. In patients where there is a concern for cauda equina syndrome, a rectal examination and perianal sensation pinprick testing should be performed. Finally, an examination of the hip joint should be routinely performed, as there is significant overlap in clinical picture between hip and spine disorders. The flexion abduction external rotation (FABER) test should be performed to rule out a sacroiliac joint pathology.

C. Causes of low back pain. Low back pain is a symptom, not a disease, and the pathologic basis of the pain frequently lies outside the spine.

- Vascular back pain. Abdominal aortic aneurysms or peripheral vascular disease may give rise to backache or symptoms resembling sciatica.

- Neurogenic back pain. Tension, irritation, and compression of lumbar nerves and roots may cause pain down one or both legs. Lesions anywhere along the central nervous system, particularly of the spine, may present with back and leg pain.

- Viscerogenic back pain. Low back pain may be derived from disorders of the organs in the lesser abdominal sac, the pelvis, or the retroperitoneal structures such as the pancreas and kidneys. Renal stones can present as severe back pain.

- Psychogenic back pain. Clouding and confusion of the clinical picture by emotional overtones may be seen. A pure psychogenic component is rare.

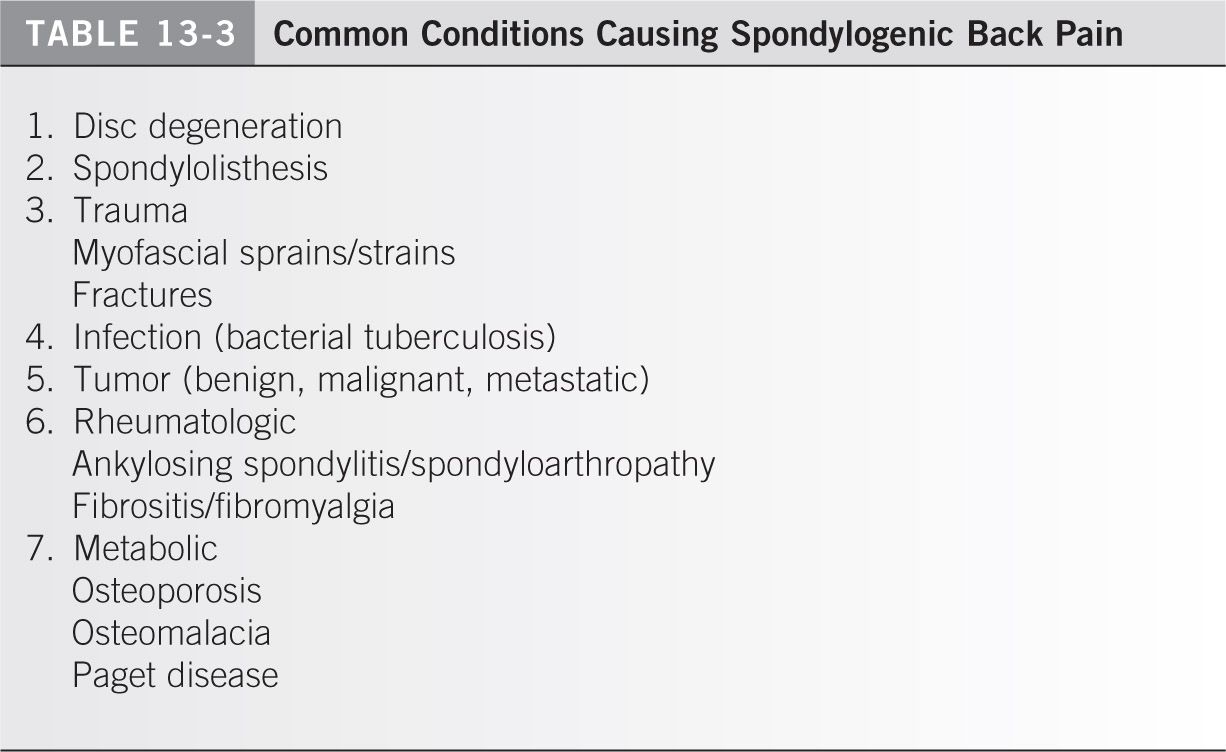

- Spondylogenic back pain. Common conditions causing spondylogenic back pain are outlined in Table 13-3.

a. Disc degeneration is by far the most common cause of back pain. Disc degeneration may occur anywhere along the spine and produce neck pain, thoracic spine pain, or lumbar or low back pain. Disc degeneration may be associated with nerve root irritation, which would then result in radicular leg pain.

- Anatomy. The spine provides stability and a central axis for the limbs that are attached. The spine has to move, to transmit weight, and to protect the spinal cord. When viewed from the side, the thoracic spine is concave forward (kyphosis) and the cervical and lumbar regions are concave backward (lordosis).

- Vertebral components

(a) Each segment of the vertebral column transmits weight through the vertebral body anteriorly and the facet joints posteriorly. Between adjacent bodies are the intervertebral discs, which are firmly attached to the vertebrae. The disc consists of an outer annulus fibrosus, which is made up of concentric layers of fibrous tissue, and a central avascular nucleus pulposus, which consists of a hydrophilic gel made of protein, polysaccharide, collagen fibrils, sparsely chondroid cells, and water (88%). The spinal cord and cauda equina are found within the spinal canal. At each intervertebral level, nerve roots leave the canal through the intervertebral foramina.

(b) A functional spinal unit or motion segment consists of two adjacent vertebrae and the intervertebral disc. It forms a three-joint complex with the disc in front and two facet joints posteriorly. The facet joints, like other joints in the body, have capsules, ligaments, muscles, nerves, and vessels. Changes in one joint affect the other two. Narrowing of the disc space, therefore, may result in malalignment of the facet joints and, with time, may lead to wear-and-tear degenerative arthritic changes in those joints.

- Normal aging is associated with a gradual dehydration of the disc. The nucleus pulposus becomes desiccated, and the annulus fibrosus develops fissures parallel to the vertebral end plates running mainly posteriorly. Small herniations of nuclear material may squeeze through the annular fissures and may also penetrate the vertebral end plates to produce Schmorl’s nodes. If the nuclear material impinges against a nerve, it may produce nerve root irritation. The flattening and collapse of the disc results in osteophytes along the vertebral bodies. Malalignment and displacement of the facet joints is an inevitable consequence of disc space collapse, leading to osteophytes that may narrow the lateral or subarticular recess of the spinal canal or the intervertebral foramina. This narrowing of the spinal canal or the intervertebral neural foramina is called spinal stenosis.

- Pain from disc degeneration without nerve root irritation. There are three patterns of low back pain associated with disc degeneration: acute incapacitating backache, which may occur a few times in a person’s life and not be a regular problem; recurrent aggravating backache, which is the most common type and is associated with regular periods of recurrence and remission of back pain; and chronic persisting backache, which is most difficult to treat and the patients have constant disabling back pain.

(a) The back pain associated with disc degeneration is mechanical in nature. It is aggravated or brought on by activity and relieved by rest in the acute phase. Rest as a treatment strategy should be limited to 1 to 2 days. There may be a referred component of back pain into the legs, but this is usually down the back of the legs and rarely goes beyond the knee. The low back pain may be due to periods of hard work, prolonged standing or walking, or prolonged sitting in one position. The peak incidence of back pain in the general population is in the 40s and 50s. This is the time when the discs have collapsed, and there is relative instability at the motion segment. The natural history, however, is for the spine to eventually stabilize with increased fibrosis around the facet joints and the discs. As the patient gets older, the physical demands become less and the spine becomes stiffer. The incidence of mechanical back pain, therefore, declines beyond the 60s.

(b) Patients who give a history of fever, weight loss, malaise, night and rest pain, morning stiffness, and colicky pain should be carefully evaluated for the possibilities of infection, tumor, spondyloarthropathy, or viscerogenic back pain.

- Disc degeneration with root irritation

(a) Nerve root irritation and compression may be due to an acute disc herniation or may be associated with spinal stenosis. Acute disc herniation results in sciatica, which typically presents with severe, incapacitating pain that radiates from the back down the leg. There may be associated paresthesias, numbness, motor weakness, or reflex changes. The pain may be constant and is frequently aggravated by coughing, sneezing, and straining. Intradiscal pressure is increased in a bending and sitting position, especially if lifting is performed, therefore increasing the amount of pain. The pain may be lessened by lying down.

(b) The most frequent sites of disc herniation are within the spinal canal, resulting in impingement of the traversing nerve root. Less commonly, a disc herniation may be located laterally in the foramen, resulting in impingement of the exiting nerve root. The leg pain or sciatica is accompanied by signs of nerve root tension, which can be diagnosed by a positive straight-leg raising test, bowstring sign, or Lasègue test.

(c) In spinal stenosis, the leg pain or radicular pain is brought on by prolonged walking or standing (neurogenic claudication). The pain may be associated with paresthesias and is relieved by sitting or stooping. There are few physical findings or neurologic deficits unless the condition has been present for a long time and is advanced. Neurogenic claudication associated with spinal stenosis should be distinguished from vascular claudication caused by peripheral vascular disease.

- Neurology of the lower extremities. The nerve roots leaving the spine at each segmental level may be affected by acute disc herniations, bony foraminal stenosis, or stenosis associated with both soft-tissue and bony compression. The nerve root may be affected within the central spinal canal either in the subarticular recess or in the intervertebral foramen. Both the traversing and the exiting nerve root may be affected. It is important to correlate the patient’s symptoms and physical findings with the abnormalities seen on radiographs, MRI scans, and CT studies. It is important, therefore, to have knowledge of the nerve roots and their distal innervation. The main nerve roots are listed in Table 13-4.

- Imaging studies

(a) Radiographs may appear normal or demonstrate disc space narrowing, osteophyte formation, or instability on lateral flexion and extension views. They are usually not helpful in acute low pain, as it has been demonstrated that there is no clear-cut correlation between low back pain and the presence of disc space narrowing on plain radiographs.1 In general, radiographs should not be obtained until the pain has persisted 6 weeks because most pain episodes are self-limited. However, in patients with red flags such as rest pain, night pain, or a history of significant trauma, anteroposterior and lateral X-rays should be obtained.

(b) Myelograms are invasive and are less commonly used. They may be used in combination with CT scans in patients who have complex problems or who have had multiple surgeries and instrumentation. Myelograms should be ordered either by or with direct consultation of the treating surgeon.

(c) CT scans are generally helpful when MRI scans cannot be obtained. They provide excellent definition of the osseous anatomy. Pars fractures are clearly identified with CT scans.

(d) MRI scans of the lumbar spine are noninvasive, provide detailed anatomic imaging, and show compromise of neural structures.

(e) Bone scans of the spine and pelvis are useful if tumor and infection are suspected, although these abnormalities can also be picked up easily on an MRI scan. A SPECT scan will distinguish between a symptomatic and an asymptomatic spondylolysis.

(f) Indications for imaging acutely in low back pain. Acute imaging is indicated only if there is a history of trauma, concern for infection or tumor, presence of a neurologic deficit, suspicion for osteoporosis, and acute fracture.

b. Spondylolisthesis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree