, James B. Galloway2 and David L. Scott2

(1)

Molecular and Cellular Biology of Inflammation, King’s College London, London, UK

(2)

Rheumatology, King’s College Hospital, London, UK

Abstract

DMARDs are a diverse range of drugs. They form a single group because they both improve symptoms and modify the course of the disease. They form the cornerstone of inflammatory arthritis management. A range of DMARDs exist. Methotrexate is most commonly used in clinical practice, followed by sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine. All DMARDs have potential adverse events and require monitoring, often with blood tests. Historically patients were treated with a single DMARD at a time (termed DMARD monotherapy). There has been a recent shift towards starting more than one DMARD at the same time (termed DMARD combination therapy) in patients with RA. This chapter will provide an overview of the different available DMARDs, their mechanisms of action, risks and benefits alongside the evidence base supporting their use.

Keywords

DMARDMethotrexateSulfasalazineHydroxychloroquineEfficacySide-EffectsBackground

DMARDs are a diverse range of drugs. They form a single group because they both improve symptoms and also, to a greater or lesser extent, modify the course of the disease. This means they reduce the progression of erosive joint damage and decrease disability [1].

Ideally DMARDs would result in remission. However, there is little evidence that they generally achieve this goal. Their failure to do so led to the abandonment of an earlier term – “remission inducing drugs”. Another collective term that has fallen out of use is “slow-acting anti-rheumatic drugs” [2]; this fell out of favour because in some patients these drugs may have relatively rapid onsets of action.

Currently Used Conventional DMARDs

Many drugs have some features of DMARDs, but only a few have been accepted into clinical practice. The use of DMARDs varies with a small number being particularly favoured. The current situation is summarised in Table 6.1. At present methotrexate is the dominant DMARD. Over 80 % of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with DMARDs who are seen in most specialist units are receiving methotrexate. Only sulfasalazine and leflunomide are also used to any appreciable extent in addition to methotrexate.

Table 6.1

The range of Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) used

Frequency of use | DMARD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Commonly used | Methotrexate | Leflunomide | Sulfasalazine |

Infrequently used | Hydroxychloroquine | Injectable gold | Azathioprine |

Rarely used | Ciclosporin | Auranofin | Cyclophosphamide |

The use of DMARDs broadly follows the strength of evidence about their efficacy. The efficacy of DMARDs involves:

Less joint inflammation with fewer swollen joints and falls in ESR and C-reactive protein

Decreased progression of joint damage, particularly erosive damage

Improved levels of disability and quality of life

The harms, or adverse events, related to DMARDs include:

Common problems to most DMARDs like low white cell or platelet counts

Unique toxicities with specific DMARDs, such as ocular toxicity with hydroxychloroquine.

A systematic review comparing trials of the main DMARDs concluded that methotrexate, sulfasalazine and leflunomide all showed similar efficacy and toxicity [3]. The main conclusions are shown in Table 6.2. One problem in these comparisons is that the trials involve one fixed dose against another fixed dose and in practice treatment is targeted at individual patients. Another problem in that older studies used doses of methotrexate that are currently considered to be suboptimal. However, for practical purposes the evidence suggests these three treatments are similar.

Table 6.2

Comparison of efficacy and harms for different DMARD monotherapies

Comparison | Leflunomide vs. methotrexate | Leflunomide vs. sulfasalazine | Sulfasalazine vs. methotrexate |

|---|---|---|---|

Efficacy | Similar improvements in joint inflammation and erosive damage | Greater improvements in joint inflammation for leflunomide | Similar improvements in joint inflammation, function and radiographic responses |

Greater improvement in functional status and health-related quality of life for leflunomide | Greater improvement in functional for leflunomide | ||

Similar work productivity outcomes | Similar radiographic responses | ||

Harms | No obvious major differences in adverse events and discontinuation rates | No obvious major differences in adverse events and discontinuation rates | No obvious major differences in adverse events |

More patients received methotrexate than sulfasalazine |

Starting DMARDs

In patients with definite rheumatoid arthritis DMARDs are started as soon as the diagnosis has been made. The evidence in favour of early DMARDs, though incomplete, is compelling. Most experts recommend starting with methotrexate.

Monitoring DMARDs

The risk of blood and hepatic toxicity means that most DMARDs require monthly blood monitoring tests. This practice began because it was possible to predict patients at risk of marrow toxicity with gold injections by prospective monitoring; this approach substantially improved safety risks. With modern treatment the risks are less clear cut and the benefits of monitoring are more questionable. However, in some patients adverse events involving the blood and liver can be detected on monitoring and such reactions carry substantial risks for patients. Consequently monitoring has become part of the standard approach to DMARD treatment [4].

Stopping DMARDs

DMARDs are stopped for toxicity and for loss of effect. Often these overlap. In patients who have entered remission or a state of low activity the benefit of continuing DMARDs is often questioned. The evidence suggests that stopping treatment in such patients often results in a disease flare; consequently it is not generally recommended [5].

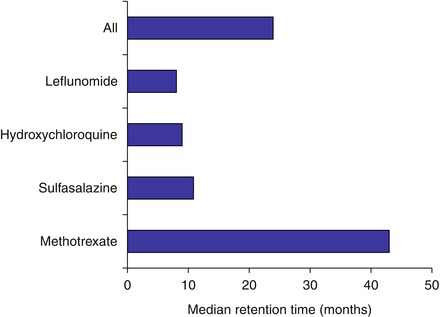

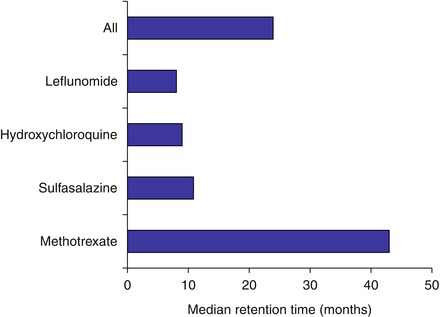

The frequency of stopping DMARD monotherapies is high. Almost half of patients initiating DMARDs discontinue treatment over the next 2–3 years. Retention rates differ across DMARDs, with patients remaining on methotrexate longer than other DMARDs (Fig. 6.1) [6]. This finding has been confirmed in many different observational studies. Such low retention rates make it particularly crucial to consider carefully the benefits and risks of discontinuing DMARDs in patients in whom therapy is controlling RA and is not causing adverse effects.

Figure 6.1

Retention rates for DMARDs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Figure adapted using data reported by Agarwal et al. [6])

Early and Late Disease

DMARD use is comparable in all stages of inflammatory arthritis. Patients who need DMARDs in early disease are equally likely to continue using them in later stages of the disease.

Intensive Treatment

Historically DMARDs were given singly – as DMARD monotherapy – but there has been a shift in practice over the last 2 years to using then in combination with each other. There are two ways of giving combination therapy:

Step-down: starting combinations together and then stopping one or more DMARDs

Step-up: starting one DMARD and then adding another if needed.

In addition combinations can involve two DMARDs, DMARDs and steroids, and DMARDs and biologics.

Ideally patients with the worst prognosis would be identified rapidly and then given intensive treatment to control their arthritis as soon as possible. However, this has proved problematic to do as at present it is difficult to identify patients with poor prognoses with sufficient accuracy to justify a policy of starting intensive DMARD combinations in specific groups of patients.

Treat to Target

The concept of “treat to target” builds on intensive management approaches in rheumatoid arthritis [7]. It sets a goal of reducing disease activity to very low levels or remission. With modern treatments this appears increasingly realistic. It should reduce long-term structural damage and improve quality of life. Treat to target involves setting a clear end point, which in this case is the target of remission, and establishing a specific treatment algorithm, which simplifies the many complex treatment sequences available to treat arthritis. However, there are some complexities. The definition of treat to target varies and a range of different data is used to justify its benefits. Some patients are reluctant to receive more intensive treatment due to concern over adverse effects. Finally, the evidence that remission is generally achievable in active rheumatoid arthritis is incomplete no matter how patients are treated.

Seronegative Arthritis

Seronegative rheumatoid arthritis responds similarly to seropositive disease. Patients with other forms of inflammatory arthritis such as psoriatic arthritis and reactive arthritis are treated in the same way as patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The evidence for using DMARDs in seronegative spondyloarthritis, particularly psoriatic arthritis, is weaker than that for rheumatoid arthritis. However, the evidence that DMARDs have different effects in any form of inflammatory arthritis is incomplete. Most rheumatologists consider they provide comparable results [8], though some experts are unconvinced about the role of methotrexate in psoriatic arthritis. One important point is that DMARDs do not appear to improve either the spinal disease or enthesopathy of seronegative spondyloarthritis [9].

Changes in Clinical Trials

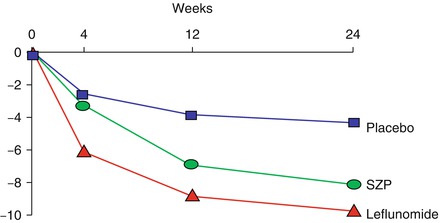

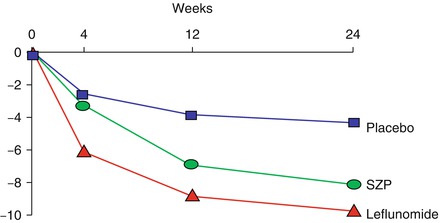

Reduction in Joint Counts and Acute Phase Proteins

When patients are treated with DMARDs there are falls in their tender and swollen joint counts over 3–6 months (Fig. 6.2). After 6 months the joint counts stabilise and they do not fall further. Although there is a small improvement with placebo, there are larger falls with active DMARDs. Whether or not the effect of placebo is due to a specific response or is an example of “regression to the mean” is uncertain. Unfortunately some residual disease activity exists. The pattern of change is similar with other assessments of disease activity, including swollen joint counts and acute phase measures like the ESR.

Figure 6.2

Falls in tender joint counts with placebo, sulfasalazine and leflunomide (Figure adapted using data reported by Smolen et al. [10])

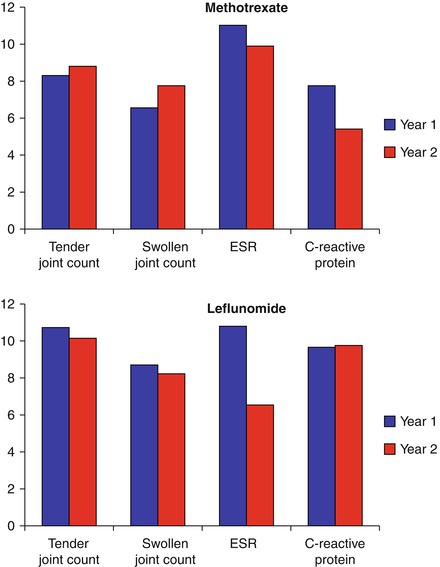

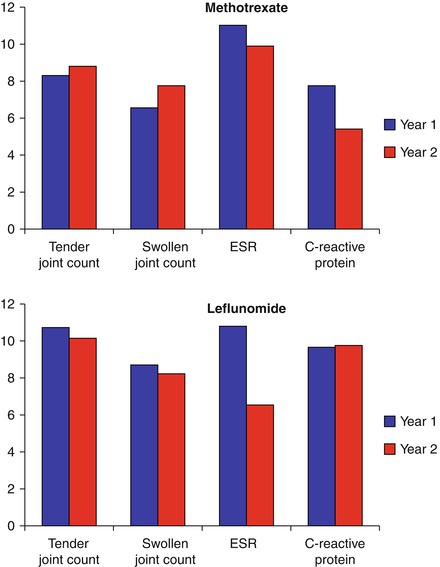

After 6 months the reductions in clinical responses are maintained as long as patients remain on treatment [11]. This is shown for 1 and 2 years in Fig. 6.3. Overall the pattern of improvements is broadly similar with methotrexate, leflunomide and sulfasalazine [10, 12]. There is no need to prefer one DMARD over another on the basis of clinical responses.

Figure 6.3

Falls in joint counts and acute phase reactants with methotrexate and leflunomide treatment (Figure adapted using data reported by Cohen et al. [11])

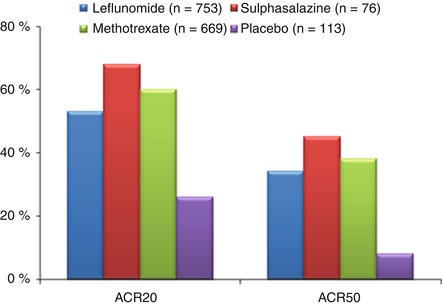

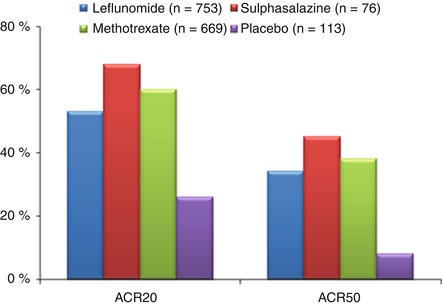

American College of Rheumatology Responses (ACR)

Effective DMARDs result in greater ACR20 and ACR50 responses over 6–12 months than placebo treatment. This is shown in Fig. 6.4 using the largest available trial data with DMARDs – the leflunomide Phase III trials – that involved the key three DMARDs and placebo treatment [13].

Figure 6.4

Changes in ACR20 and ACR50 responses with DMARDs (Figure adapted using data reported by Scott and Strand [13])

Improved Disability

DMARDs improve disability over 12 months or longer, especially in those patients who remain on treatment. This is seen with all major DMARDs. Health Assessment Questionnaire scores decreased by about one third with effective DMARD therapy and remained thereafter at this lower average level.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree