Chapter 14 Diet and complementary therapies

KEY POINTS

A combination of weight loss/healthy eating and exercise is recommended in the management of osteoarthritis

A combination of weight loss/healthy eating and exercise is recommended in the management of osteoarthritis Weight loss and avoidance of alcohol can ameliorate the symptoms of gout and prevent future episodes

Weight loss and avoidance of alcohol can ameliorate the symptoms of gout and prevent future episodesSECTION 1 DIET AND DIETARY THERAPIES

At some point, health professionals working in the area of musculoskeletal conditions will be asked by patients about the role that diet can play in managing their symptoms. Diet is one issue which is very important to many patients and may have a more important role than many health professionals acknowledge (Rayman & Pattison 2008). Dietitians are not yet widely viewed as core members of the rheumatology team and may not be easily accessed, thus it is important that some dietary issues can be safely addressed by other health professionals. This chapter will provide an overview of basic nutritional requirements for healthy eating in general and a more in depth examination of the available evidence for dietary advice in common musculoskeletal conditions. Dietary intervention usually involves adding a food, nutrient or substance to the diet for example a dietary supplement or removing food from the diet or making a total change to dietary intake. In general, diets are perceived to be harmless but, uninformed and unnecessary dietary restrictions will disturb normal diet and lifestyle patterns, increase the risk of nutritional deficiencies and even adversely affect medical treatment. Therefore, it is important to recognise when expert advice is necessary. To deal with this, two scenarios are discussed in the case studies at the end of this chapter.

HEALTHY EATING

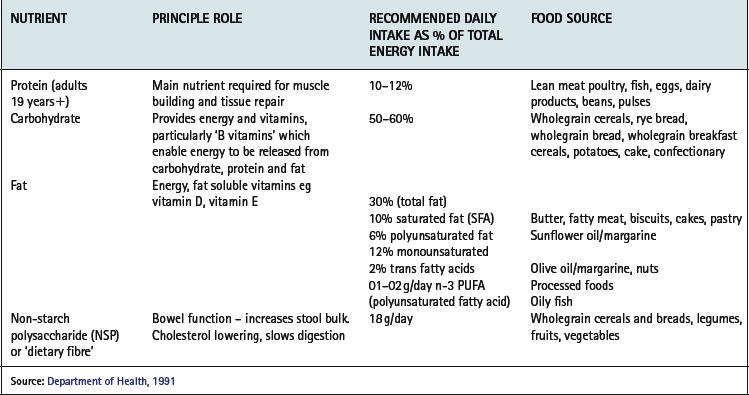

A healthful diet is based on a varied intake of wholegrain cereals, low fat dairy products, fish and lean meats, olive oil based oils and margarines, fruit and vegetables, beans and pulses, is therefore low in fat, especially saturated fat, salt and sugar but adequate in energy, protein and fibre (Tables 14.1, 14.2).

Table 14.2 Food groups and targets for intake

| FOOD GROUP | TARGETS FOR DIETARY INTAKES |

|---|---|

| Bread, potato, cereals, rice, flour, pasta | Average 6–11 portions/day (eg 1 portion = 1 slice bread) Use wholegrain and white |

| Sugars, sweets, biscuits, cakes | Eat ‘in moderation’ |

| Fats: butter, margarine, oil | Use olive oil & olive oil-based products Grill, poach, bake, steam instead of frying |

| Dairy products | ½-1 pint milk/day (any type) 4–5 yogurts a week 4–6 portions cheese a week (1 portion = 25 g) Use low fat products |

| Lean meat (beef, pork, lamb) | 2–3 portions a week |

| Poultry | > 2–3 portions a week |

| Fish (all types) | ≥ 2 portions a week |

| Eggs | 2–3 a week |

| Fruit & vegetables | 5 portions daily: 1 portion = 1 apple, 3 dried apricots,1 cereal bowl of mixed salad, 2 broccoli florets |

| Alcohol | Women ≤ 14 units/week Men ≤ 21 units/week (1 unit = ½ pint lager/beer (3–4% ABV); 125 ml glass wine (∼12% ABV); 1 pub measure of spirits) |

NUTRITION IN MUSCULOSKELETAL CONDITIONS

There is an enormous amount of dietary advice aimed at people with arthritis, particularly rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Unfortunately, the vast majority of claims made by self-styled diets for arthritis such as The Dong diet, Sister Hill’s diet, Norman F. Childer’s diet, and many more, are unsubstantiated, based on individual experience and cannot be generalised to everyone with the condition. Undertaking high-quality dietary intervention studies is complex and extremely difficult to do, thus ‘high-level’ evidence of efficacy of a dietary intervention is often lacking. Also, studies measure diverse outcomes making interpretation of the results more difficult. For example, global measures of well being and assessment of pain are more susceptible to placebo effect and convey a different message than measurements of objective, clinical outcomes. In addition, dietary advice recommended for other clinical conditions may be contradictory, thus adding confusion. The following section summarises dietary advice for which there is some evidence of efficacy in the rheumatic diseases.

FISH OILS AND OMEGA-3 FATTY ACIDS

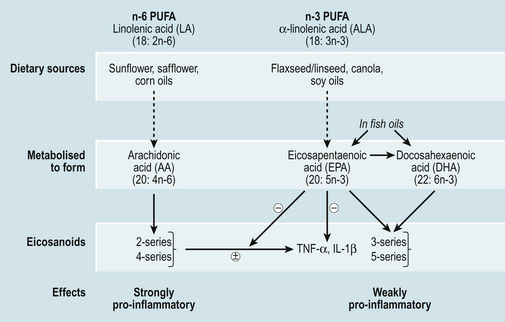

The majority of evidence for the beneficial effects of fish oils in the management of arthritis comes from studies in RA. Long chain omega-6 (n-6) and omega-3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are precursors of inflammatory mediators such as eicosanoids (Fig. 14.1) Metabolism of n-6 PUFA, yields arachidonic acid, a precursor of strongly inflammatory leukotrienes, prostaglandins and thromboxanes (two and four series) (Fig. 14.1), whereas n-3 PUFA are converted to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and further to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) which yield less inflammatory eicosanoids (three and five series). EPA and DHA are obtained from dietary sources found mainly in oily fish such as mackerel, sardines, halibut, herring, salmon, trout and fresh tuna (not tinned), whereas n-6 PUFAs are much more abundant in the diet for example in seeds, vegetable oils and margarines. The conversion pathways of n-3 and n-6 PUFA are shared, consequently they are in competition for the same enzyme necessary for adaptation (Fig. 14.1). So, in addition to advising patients to increase their intake of n-3 PUFA from fish or supplements, a reduction in the intake of n-6 PUFA may increase the effectiveness of n-3 PUFA supplements. This could be achieved by replacing sunflower oils/margarines with olive or rapeseed oils and olive oil based margarines.

There is good evidence for a therapeutic benefit of n-3 PUFA (EPA + DHA) in patients with RA if taken as fish oil supplements (Fortin et al 1995). A more recent systematic review of the same intervention studies, but specifically exploring pain control in people with RA, concluded that the amount of n-3 PUFA necessary to achieve a reduction in pain is 2.7–3 g/day (total EPA + DHA) for 3–4 months, that is, the maximum duration of these studies (Goldberg & Katz 2007).

The proportion of EPA and DHA in fish oil supplements varies greatly between products but it is possible to achieve an intake of 2 g n-3 PUFA from four or five fish oil capsules, containing 500 mg or more n-3 PUFA. The number of capsules required will also vary depending on oily fish consumption. Liquid fish oil preparations are more concentrated sources of n-3 PUFA and are often flavoured to improve tolerance.

Many ‘one-a-day’ type cod liver oil capsules contain high amounts of the fat soluble vitamins A and D. It is considered unsafe to take high doses of vitamin D long-term because of the risk of hypercalcaemia and hypercalciuria and also unsafe to take high doses of vitamin A because of toxicity or a possible increase in hip fracture. Pregnant women should avoid cod liver oil supplements because of the unknown tetratogenic effects of vitamin A at high doses (Rayman & Callaghan 2006a). Therefore, all patients should be advised to use fish body oil supplements.

N-3 PUFA rich fish oils have also been shown to be effective in secondary cardiovascular disease prevention (Mead et al 2006). Given that people with RA are at an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (Goodson & Solomon 2006), eating oily fish more than twice a week can be recommended. There has been concern over high levels of toxic substances such as dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and mercury levels in oily fish and fish oil supplements. The Food Standards Agency (FSA) recommends two portions of fish a week one of which should be oily for the general population. For people who want to eat more oily fish, the FSA has set a maximum of four portions of oily fish per week (Food Standards Agency 2002). Women of reproductive age and girls should limit their intake of oily fish to one portion a week and should avoid swordfish, marlin or shark because of high mercury levels. There is also a Europe wide dioxin limit which manufacturers of fish oil supplements adhere to so toxicity from these should not be a problem. People on anti-coagulation therapy should seek guidance from their medical practitioner before taking high doses of fish oil.

PLANT SOURCES OF N-3

EPA and DHA can be synthesised from α-linolenic acid (ALA) found most commonly in green leafy vegetables, flaxseeds, rapeseeds and canola oils, although the conversion of ALA to EPA and DHA is relatively inefficient. There is little evidence to support the efficacy of these oils in the management of rheumatic diseases (Rennie et al 2003). On the other hand, there is some supporting evidence for gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) supplementation. GLA is produced from n-6 linoleic acid and is found in plant oils such as evening primrose oil, blackcurrant seed and borage seed oils (Leventhal et al 1993, Little & Parsons 2001a, 2001b, Watson et al 1993). However, results are inconsistent and more research is required in this area before recommendations can be made.

NUTRITION IN OTHER CONDITIONS

There is some evidence ‘in vitro’ that long chain n-3 PUFAs, can affect the metabolism of osteoarthritic cartilage (Curtis et al 2002), but this is not sufficient to recommend high dose fish oil therapy in this group of patients. Patients with gout may be required to follow a diet low in dietary purines. Oily fish are rich in purines and may need to be avoided if gouty symptoms are exacerbated by the consumption of oily fish.

FRUIT, VEGETABLES AND ANTIOXIDANTS

Dietary antioxidants are of particular interest in the management of arthritis. These ‘phytochemicals’ are found extensively in fruits and vegetables particularly brightly coloured varieties such as oranges, apricots, mangos, carrots, peppers/capsicum, and tomatoes and in green leafy vegetables. The most common antioxidants are vitamins C, E and A, but there are many more, such as the carotenoids β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin. Antioxidants play a crucial role in our internal defence system protecting against harmful metabolites and other substances. There is some evidence that higher dietary intakes of some antioxidants may lower the risk of developing inflammatory arthritis (Pattison et al 2004, 2005) and possibly dampen down the inflammatory response in established disease (Pattison et al 2007). However, this theory is based on epidemiological evidence of dietary intake in inflammatory arthritis. A recent systematic review did not support the use of individual antioxidant supplementation (vitamins A, C, E and selenium) in the treatment of any type of arthritis (Canter et al 2007).

In OA, a higher dietary intake and higher serum levels of vitamin D were associated with a lower risk of knee OA progression (McAlindon et al 1996) but more recent data from two large epidemiological studies of OA have not confirmed this association (Felson et al 2007). Results from a UK intervention study of vitamin D supplementation in established OA knee are awaited.

Anaemia is common in people with RA, usually as a manifestation of the anaemia of chronic disease associated with RA. Mild iron deficiency may actually be beneficial and suppress joint inflammation (Rayman & Callaghan 2006b). Therefore iron supplementation may be detrimental and is not recommended unless under medical supervision.

VEGETARIAN AND VEGAN DIETS

The effects of vegetarian and vegan diets have been investigated in people with RA but not OA (Hafström et al 2001). The pooled results of the only four controlled studies found long-term clinical benefit for patients with RA after fasting followed by a vegetarian diet for three months or more (Müller et al 2001). If followed appropriately, vegetarian diets should not cause nutritional problems. However, vegan diets are much more nutritionally restrictive and may result in excessive weight loss. Patients should be encouraged to seek dietetic support. ‘Living food’ diets (uncooked, vegan diet) (Hänninen et al 2000) and gluten-free diets have also been evaluated in patients with RA but there is as yet little consistent evidence of their efficacy.

MEDITERRANEAN-TYPE DIET

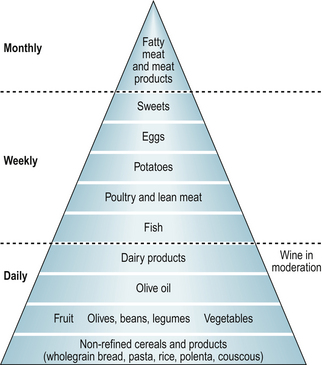

This way of eating is based on daily intakes of fresh fruits and vegetables, nuts, beans and pulses, olive oil, wholegrain cereals and regular oily fish and poultry consumption (Fig. 14.2). Thus, the diet contains n-3 PUFAs, olive oil, antioxidants, dairy products and unrefined carbohydrates. In a recent study, Swedish patients with RA who followed a modified Mediterranean diet for 3 months reported reduced inflammatory activity, increased physical functioning and improved vitality compared with those who followed the control diet (Sköldstam et al 2003). No such studies have been undertaken in people with OA.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree