Diastasis of the Symphysis Pubis: Open Reduction Internal Fixation

David C. Templeman

Andrew H. Schmidt

S. Andrew Sems

Indications/Contraindications

The pubic symphysis is a cartilaginous joint where the pubic bones meet. The articulation is composed of a fibrocartilaginous disc that is reinforced by the superior and inferior pubic ligaments. The arcuate ligament forms an arch between the two inferior pubic rami and is thought to be the major soft-tissue stabilizer of the symphysis pubis (1).

Injuries to the pubic symphysis include diastasis, fractures into the symphysis, and fracture-dislocations. Following trauma, if the pubic symphysis is not disrupted, the anterior pelvic-ring injury commonly consists of pubic rami fractures. These fractures are usually vertically oriented but may be comminuted or horizontal (2). Diastasis of the symphysis pubis rarely coexists with fractures of the pubic rami (3,4).

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is usually indicated when diastasis of the pubic symphysis exceeds 2.5 cm. Internal fixation is performed to relieve pain and improve stability of the anterior pelvic ring. The indications for surgery are based on the patient’s overall condition and the stability of the entire pelvic ring.

Several different classifications can be used to characterize pelvic injuries. Early classifications were based on either the location of the fracture or the mechanism of injury. Most modern classifications, however, are based on the degree of pelvic stability (5,6). The Tile classification of pelvic ring injuries is used to predict the mechanical instability of the injured pelvic ring and are categorized as A, stable; B, rotationally unstable but vertically stable, and C, rotationally and vertically unstable. Tile B and C injuries may have associated disruption of the symphysis pubis (6).

Diastasis of the symphysis pubis and external rotation of one innominate bone results in the so-called “open-book” injury. This is a Tile B injury in which the posterior pelvic ligaments are intact and prevent cephalad displacement of the involved innominate bone.

When disruption of the symphysis pubis is greater than 2.5 cm, internal fixation is indicated. Displacement of this magnitude is thought to be accompanied by injuries to the sacrospinous ligament and the anterior sacroiliac ligaments, which are thought to allow the involved innominate bone to rotate externally. Stable fixation of the symphysis is sufficient to correct this innominate-bone instability (2).

In Tile C injuries, the symphysis pubis (or the anterior pelvic ring) is disrupted as is the posterior pelvic ring, resulting in complete instability of the pelvis. Fixation of the anterior ring alone is insufficient to restore pelvic stability and must be accompanied by reduction and fixation of the posterior pelvic injury (6,7).

Contraindications to internal fixation of the symphysis pubis include unstable, critically ill patients; severe open fractures with inadequate wound debridement; and crushing injuries in which compromised skin may not tolerate a surgical incision. Suprapubic catheters placed to treat extraperitoneal bladder ruptures may result in contamination of the retropubic space and is a relative contraindication to internal fixation of the adjacent symphysis pubis. Additional conditions that may preclude secure fixation are osteoporosis and severe fracture comminution of the anterior pelvic ring.

When the diastasis of the symphysis pubis is less than 2.5 cm, internal fixation is seldom necessary. Patients may be safely mobilized and allowed to exercise toe-touch weight bearing on the side of the externally rotated hemipelvis. Radiographs are repeated within the first few weeks to ensure further displacement has not occurred. By 8 weeks, the pelvis is usually healed enough to allow full weight bearing. Any increase in pain associated with activity must be evaluated with radiographs so hardware failure or late instability can be detected.

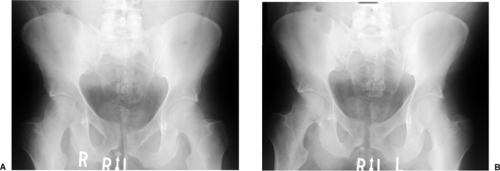

Chronic pelvic-ring instability may follow nonoperative treatment or unrecognized pelvic-ring injuries. This subset of patients commonly presents with pain in the symphyseal or sacroiliac region when undergoing weight-bearing activities. For this group of patients, single leg stance radiographs may be useful. The radiographs are taken as standard anteroposterior (AP) pelvis x-rays, and the three-film series should include a standing AP pelvis as well as an AP of the pelvis during left leg stance and an AP of the pelvis during right leg stance. Subtle instability may manifest as a vertical displacement at the symphysis pubis with single leg stance on the unstable side (Fig 38.1). These chronic instabilities may be approached with the same technique of fixation that one would use to treat an acute injury, but retropubic scarring of the bladder to the posterior aspect of the pubic bones and symphysis may be encountered.

Preoperative Planning

To determine the direction and magnitude of the symphysis pubis disruption and the relative position of the pubic bones, the surgeon should obtain AP, 40-degree caudal and 40-degree cephalad views (Fig. 38.2A–C). Differences in the height of the pubic rami usually indicate that the hemipelvis is displaced in more than one plane. The most common deformity associated with disruption of the symphysis pubis is cephalad migration, posterior displacement, and external rotation of one hemipelvis (5). This pattern indicates a posterior pelvic injury (Tile C) that requires posterior reduction and internal fixation to achieve a stable pelvis (6,7,8).

Patients with hemodynamic instability require immediate evaluation and resuscitation. A multidisciplinary team consisting of general surgeons, orthopedists, urologists, and interventional radiologists is frequently required to treat patients with multiple injuries (9,10,11,12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree